Neural Networks: The Integrated Self and Its Disintegration

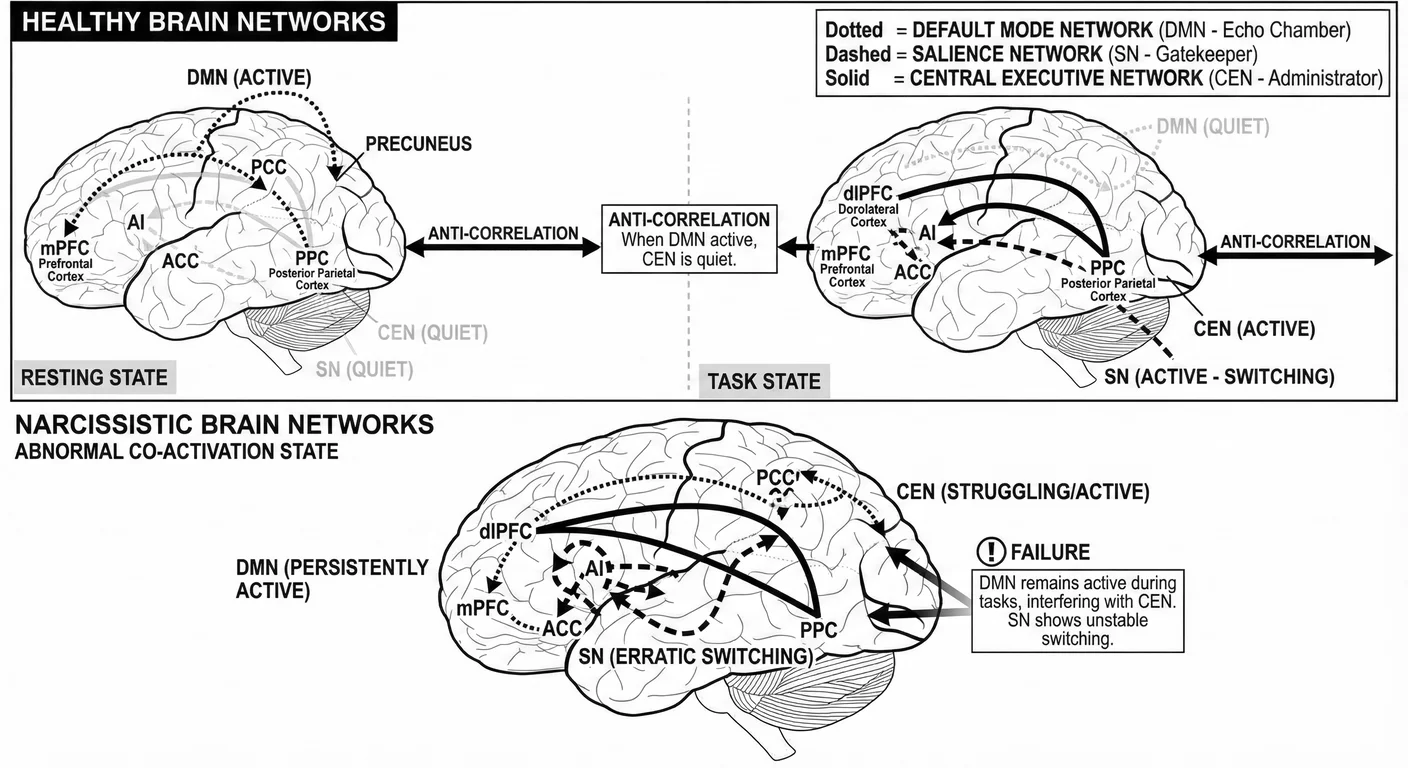

Neural networks usually operate in harmony. They switch on and off in coordinated rhythms, like different sections of the palace coming alive in sequence as people (information) flow smoothly between the chambers. Almost everywhere we have visited in a narcissistic brain, these networks show significant dysregulation. Some are hyperconnected, locked in rigid patterns. Others fail to communicate or, worse, their signalling is disrupted. This is what makes the maze a maze. The interior wiring creates endless loops where thoughts circle back to self and where external focus is constantly hijacked by internal rumination.

The Echo Chamber: The Daydreaming Self

When the brain is not focused on any external task—a network activates that neuroscientists call the Default Mode Network (DMN) Default Mode Network (DMN) A brain network active during self-referential thinking and introspection, showing abnormal connectivity in narcissists that may explain their self-focused processing. . We call it the Echo Chamber. For most people, this network maintains our sense of continuous self and enables the mental time travel that creates narrative identity. We daydream, skip forwards and back in time across speculative timelines, and explore avenues of possibility, while still loosely tethered to the present as if on holiday. In NPD, this Echo Chamber is less of a holiday and more akin to a prison of rumination.

The Default Mode Network shows increased internal connectivity but cannot properly switch off during external engagement 410 . The narcissist cannot readily shift between internal focus and engaging with others. The mind becomes an echo chamber where the self reverberates endlessly.

As with the individual brain structures, this whole network shows increased activation to positive self-relevant information but decreased activation to negative self-relevant information 157 . It is almost as if the brain is actively filtering experience to maintain grandiose self-perception and protect the false self. While healthy brains show fluid transitions between daydreaming and focus, the narcissistic brain remains locked in these patterns of self-referential processing 586 . The maze has many passages but they all lead back to the same distorted mirror of false-self.

If one lives with a narcissist, one will know this pattern intimately. They cannot fully engage with those present. They always seem elsewhere: their attention a film over deeper preoccupation. Any topic reverts to them within moments. The same grievances and triumphs are rehearsed endlessly.

Non-narcissists usually spot these as triggers, showing insight and trying to move away from them. But with narcissists, the other person’s presence barely registers unless that person is being discussed. It feels like they are looking at an internal screen, experiencing other people as periphery. It may be rude, but it is also architecture.

The Gatekeeper: What Gets Attention

A brain network decides attention priority—what neuroscientists call the salience network. We call it the Gatekeeper. It switches between internal focus (daydreaming) and external focus (engaging with the world). Predictably, in NPD, this switching mechanism favours self-relevant information while missing important social and emotional cues.

A key part of the Gatekeeper is the brain’s feeling centre, the Anterior Insula Anterior Insula A brain region crucial for self-awareness, empathy, and processing emotions—showing reduced activity in narcissists when processing others' suffering. , which creates our moment-to-moment sense of empathy, bodily self, and emotional awareness. This region shows reduced volume in NPD 273 . When this region is compromised, narcissistic individuals often experience alexithymia—Greek for “no words for emotions”—and struggle to identify their own feelings.

The Gatekeeper in NPD shows erratic switching 852 . Sometimes it locks onto self-relevant information with unusual intensity; sometimes it misses important social cues entirely. The palace’s communication system is broken, with some alarm bells ringing constantly while others remain forever silent. While the ringing ones are a nuisance, the silent ones destroy personal and professional relationships.

The Administrator: Focus and Its Failures

The central executive network (CEN), comprising the Chief of Staff region of the prefrontal cortex (Throne Room) and connecting areas, serves as the Administrator. It enables goal-directed behaviour, maintains task focus, and exercises conscious control of our tasks. In NPD, this network operates in a state of chronic compensation, working harder to achieve less.

Narcissistic individuals show increased Administrator activation during cognitive tasks, but this extra activity does not translate to better performance 258 . Their brain expends more neural resources to maintain the same level of cognitive function, much like a computer running too many background programmes.

Normally, when the Administrator is active, the Echo Chamber quiets: one cannot daydream and focus at the same time. One has to switch channels. In NPD, this suppression fails. 267 They cannot fully suppress self-referential processing even during demanding external tasks, and so receive both channels simultaneously.

The Administrator exerts reduced top-down influence on emotional structures while receiving increased bottom-up influence from these same structures. 424 Emotion drives cognition more than cognition controls emotion. The Ruler is not truly in charge, as it constantly responds to emotional demands from below.

The Corpus Callosum: The Divided Self’s Failed Bridge

The corpus callosum, or the Bridge—200 million nerve fibres connecting the brain’s hemispheres—is the largest white matter structure in the human brain. It enables the two halves of the brain to function as an integrated whole. In the narcissistic brain, this essential Bridge shows structural and functional alterations that may underlie the fragmented self hidden beneath grandiose facades.

The corpus callosum is not a uniform cable but a heterogeneous structure with distinct regions carrying different types of information. The genu (Latin: “knee”)—the Emotional Bridge, connecting prefrontal regions—links areas involved in executive function and emotional regulation. The body—the Motor Bridge—links motor and somatosensory areas. The splenium—the Sensory Bridge—connects occipital and temporal regions processing visual and auditory information. In NPD, each region shows distinct alterations that collectively fragment the self 558 .

Brain scans reveal reduced structural integrity throughout the Bridge in individuals with NPD, with the most pronounced damage in the front portion connecting emotional regulation centres 1294 . This compromised connectivity may explain the difficulty integrating emotional experience with cognitive control, leading to the emotional volatility characteristic of narcissistic injury.

The anterior corpus callosum (the Emotional Bridge), connecting regions involved in emotional processing and regulation, shows distinct functional alterations. During emotional conflict tasks, where the two hemispheres must coordinate to resolve competing emotional information, individuals with NPD show delayed interhemispheric transfer times 73 . The hemispheres thereby cannot quickly agree on emotional meaning and end up creating microseconds of internal conflict, an eternity in neural time, that then accumulates into the chronic emotional instability of NPD.

Split-brain studies reveal that each hemisphere can maintain separate self-concepts. Even with an intact corpus callosum, functional imaging reveals a similar phenomenon in narcissism: the hemispheres maintain partially independent self-representations that fail to fully integrate. 446 The left hemisphere’s verbal, grandiose self-narrative does not fully integrate with the right hemisphere’s embodied emotional self-experience.

The result is a false self that is simultaneously grandiose and empty. This neurobiological division provides a partial basis for the false self described throughout this work—the grandiose performance masking deep vulnerability, a structure that cannot integrate because its very foundation is divided.

The corpus callosum normally shows task-dependent dynamic changes in functional connectivity, strengthening interhemispheric communication when cognitive demands require hemispheric cooperation. The narcissistic brain impairs this dynamic modulation. The Bridge maintains a rigid pattern of connectivity regardless of task demands 130 —it cannot adjust its traffic flow, creating cognitive inflexibility and the persistent self-focus that characterises narcissistic cognition.

The Bridge also plays a role in self-recognition. The right hemisphere specialises in self-face recognition, while the left hemisphere processes self-narrative. The Bridge integrates these into unified self-awareness. In NPD, neuroimaging during self-recognition tasks reveals asynchronous activation between hemispheres, with the left hemisphere’s narrative self-enhancement preceding and potentially overriding the right hemisphere’s more accurate self-perception 641 .

The healthy faculty where one hemisphere suppresses the other through callosal connections is expressed very differently in NPD. Typically, this inhibition prevents redundant processing and enables hemispheric specialisation. In narcissistic individuals, excessive left-to-right inhibition during self-referential processing may suppress the right hemisphere’s capacity for self-criticism and realistic self-appraisal 129 . The grandiose left hemisphere silences the more realistic right.

The corpus callosum’s (the Bridge’s) role in empathy shows the deficit clearly. Empathy requires rapid interhemispheric integration: the right hemisphere’s emotional resonance must combine with the left hemisphere’s cognitive understanding. Delayed callosal transfer during empathy tasks correlates with reduced empathic accuracy 296 . The hemispheres cannot quickly enough combine feeling and thinking about others’ experiences.

Developmental studies demonstrate that the corpus callosum continues maturing into the mid-twenties, with ongoing myelination improving interhemispheric communication. Early relational trauma, common in NPD histories, disrupts this protracted development. Childhood emotional neglect predicts reduced corpus callosum size in adulthood, particularly in regions connecting emotional processing areas 1216 . Early trauma weakens the Bridge between hemispheres before it fully develops.

The corpus callosum in NPD actively maintains this fragmentation. Its dysfunction prevents the integration necessary for coherent identity and empathic connection. The narcissistic self is not just wounded—it is structurally split, with hemispheres that cannot fully communicate their different truths.

We recognise this in daily life: grandiose persona in public, crumbling in private. Confident words contradicted by anxious body language. They seem like two different people depending on context, unable to reconcile their self-image with their behaviour. They are neurologically divided—literally two minds that struggle to become one. Both are real, neither is stable, and the individual may be as confused about their identity as those who observe them.

Back in the cafe, Molly watches Jackson’s face as he talks about his business partner’s betrayal. His left hemisphere narrates the injury with eloquent outrage. But she can see something else—a flicker of uncertainty, a tension in his jaw that contradicts his confident words. Two stories, told simultaneously. She wonders which one is true. The answer, had she known to ask, is both.

The Emotional Mirror: Broken Mirrors and Failed Resonance

Mirror neurons—cells that fire both when performing an action and when observing it, forming the basis for imitation and empathy—have given us deep insight into how our brains encode and express empathy. We call this system the Emotional Mirror. When we see someone smile, our smile neurons fire; when we see someone in pain, our pain networks activate—automatic, pre-reflective understanding of others’ experience 1038 . In the narcissistic brain, this mirroring system is miscalibrated.

The Emotional Mirror is selective and conditional in narcissism. Individuals show normal or even enhanced mirror neuron activation when observing others who are similar to themselves—family members, admirers, those who reflect their idealised self-image 587 . But when observing dissimilar others or those who threaten self-esteem, mirror neuron activation is significantly reduced or absent. The mirrors only reflect selected images. The idealisation-devaluation cycle follows: the brain mirrors only those who enhance the narcissistic self-image.

Mirror neurons that normally respond automatically to others’ pain stay silent in narcissists—unless the pain relates to themselves 1144 . Show a narcissistic individual an image of someone’s hand being pierced, and their pain circuits remain quiet. But tell them this could happen to them, and suddenly the mirror neurons fire with full intensity. Resonance capacity exists but requires self-relevance to activate. This neurobiologically grounds the empathy deficit: cognitive empathy preserved alongside severely impaired emotional empathy.

NPD also alters the Emotional Mirror’s connectivity with the limbic system. Normally, mirror neuron activation triggers corresponding emotional responses through connections with the Alarm Bell and the Feeling Centre. In narcissistic individuals, this mirror-to-emotion pathway is weakened 1121 . They can understand others’ emotions intellectually but do not feel them somatically—cognitive empathy without affective resonance.

Mirror neurons require proper input during critical periods. The infant who looks to their caregiver’s face and sees distortion or self-preoccupation develops a mirroring system calibrated to abnormal patterns 1236 . The broken mirrors of childhood become the broken mirror neurons of adulthood.

This explains something survivors find maddening: the narcissist can seem intensely empathic—when it suits them. They mirror your emotions perfectly during idealisation, then go cold. They read social situations brilliantly when status is at stake, yet seem blind to your distress while remaining acutely aware of your admiration. Mirror neurons fire selectively: activated by admirers, suppressed for those who do not reflect the grandiose self. When you become a separate person with separate needs, the mirror goes dark. If mirror neurons retain plasticity—and evidence suggests they do—perhaps these broken mirrors can be gradually repaired, one reflection at a time.

The Chemical Architecture of Narcissism

The molecular messengers that carry information between neurons operate at a deeper level than structures or networks. These neurotransmitters— Dopamine Dopamine A neurotransmitter associated with reward, motivation, and pleasure—hijacked in narcissistic relationships through intermittent reinforcement creating addiction-like attachment. , serotonin, GABA, glutamate, opioids, Oxytocin Oxytocin The 'bonding hormone' released during intimacy and connection—manipulated in narcissistic relationships to create attachment despite abuse. —are the chemical vocabulary in which the brain speaks to itself.

The palace tour has covered architecture, rooms, wiring and communication systems. Now: the actual language spoken within—beyond structure, into content and meaning. This is where biology becomes tangible, measurable, amenable to intervention.

In the healthy brain, these neurotransmitter systems maintain exquisite balance. The palace’s chemical climate is stable: enough dopamine for motivation but not compulsion, sufficient serotonin for mood stability, proper GABA to inhibit excess, adequate glutamate to excite without toxicity. Yet in the narcissistic brain, this chemical architecture is severely disrupted. The maze runs on corrupted chemistry—dopamine systems hijacked by the pursuit of admiration, serotonin depleted until emotional storms rage, GABA failing to inhibit, oxytocin perverted from connection into manipulation.

The Addiction Systems: Craving and Withdrawal

The Dopamine System: Reward and the Addiction to Admiration

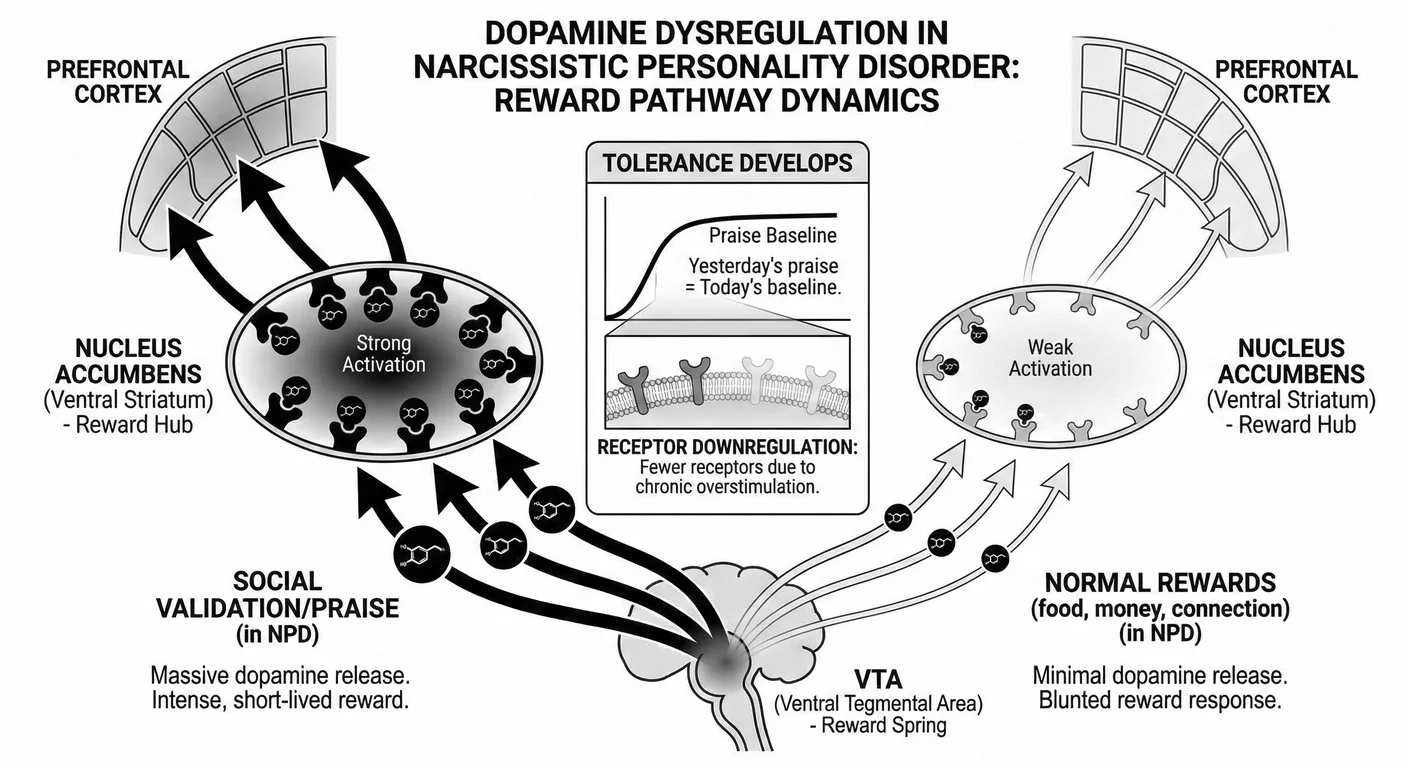

The narcissist chases admiration with the desperation of an addict seeking their next fix. Dopamine, the Desire Chemical—the neurotransmitter driving reward anticipation and motivation—originates in the ventral tegmental area (the Reward Spring) and substantia nigra (the Rhythm Keeper). In the narcissistic brain, this system becomes hijacked by the pursuit of validation, creating an addiction-like dependence on admiration.

PET imaging studies using radiolabeled dopamine ligands reveal that individuals with NPD show increased dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (the Reward Hub) in response to praise, but diminished release in response to monetary rewards or food 1281 . The reward system has been recalibrated to prioritise social status over other forms of reward.

The mesolimbic pathway—the Desire Road connecting the VTA to the nucleus accumbens—shows strengthened connectivity in narcissistic individuals during anticipation of self-relevant feedback 112 . The mere possibility of praise or criticism activates strong dopaminergic signalling, creating the intense anticipation and anxiety around evaluation that characterises NPD.

Genetic studies have identified polymorphisms in dopamine receptor genes, particularly DRD4 and DRD2—genes affecting reward sensitivity and novelty-seeking—that correlate with narcissistic traits 345 . The 7-repeat allele of DRD4, associated with novelty-seeking and reduced dopamine receptor efficiency, is overrepresented in individuals with NPD. The narcissistic brain may be wired to require more stimulation to achieve the same reward response.

NPD alters the dopaminergic system’s role in prediction error—the difference between expected and received rewards. When praise is less than expected, the negative prediction error signal is amplified. When praise exceeds expectations, the positive signal is blunted 1103 . The narcissistic brain is better at detecting disappointment than satisfaction, driving an endless pursuit of ever-greater validation.

One can spot the signs: they need increasing doses of praise to achieve the same effect. They become irritable and restless when validation is withheld. They pursue admiration even when it damages relationships or career. The high of success is brief; the crash is prolonged. The dopamine system has been hijacked by social validation. Like any addiction, tolerance develops: yesterday’s praise shifts into today’s baseline. The withdrawal symptoms—the irritability and desperate seeking—are neurochemistry hardening into character.

Jackson closes a major deal and feels, for perhaps an hour, like a god. By dinner he is restless, checking his phone for congratulatory messages. By bedtime the triumph has faded to grey and he lies awake cataloguing the ways it could have gone better. Molly’s praise—I’m so proud of you—registers for perhaps thirty seconds before his brain recalibrates. He needs something more. He always needs something more.

The Internal Opioid System: Validation as Neural Addiction

The brain’s internal opioid system (the Bonding Chemistry: the body’s natural pain-relievers and pleasure chemicals, including endorphins) regulates pain and social bonding. These natural opiates create the warm glow of connection and the numbing of pain. In the narcissistic brain, this system has been commandeered, transforming admiration into an addictive substance as powerful as any external drug.

Beta-endorphin, the brain’s primary internal opioid, releases during positive social interactions, creating feelings of wellbeing and connection. PET imaging using opioid receptor ligands reveals a disturbing pattern: reduced baseline opioid receptor binding (suggesting chronic overstimulation) but excessive endorphin release in response to praise and admiration 1371 . The narcissistic brain has become addicted to validation, showing the same receptor downregulation and tolerance seen in substance addiction.

The mu-opioid receptor system shows particular alterations. Genetic variations that increase opioid sensitivity are overrepresented in grandiose narcissism 1306 . The consequence: they experience more intense pleasure from validation but also more severe withdrawal when supply is cut. Their brains are primed for addiction.

“Narcissistic withdrawal” carries a clear neurobiological signature. Depriving NPD individuals of admiration plummets their endogenous opioid levels—creating genuine physiological withdrawal: dysphoria, physical discomfort 662 . Brain imaging during these periods shows the same altered activity patterns in the Reward Hub and Throne Room as drug withdrawal. Validation-seeking is addictive.

The kappa-opioid system—the Dysphoria Generator, producing dysphoria and aversive states when activated by stress and rejection—shows hyperactivity in vulnerable narcissism. Dynorphin, the primary kappa-opioid peptide, is elevated in response to social rejection or criticism 234 . The intense dysphoria of narcissistic injury follows—psychological pain compounded by activation of the same neural systems that create the anguish of drug withdrawal.

The opioid system also shapes social bonding. In typical development, endogenous opioids released during positive social interactions create the neural basis for attachment. But in NPD, this system responds primarily to admiration rather than genuine connection. Brain imaging demonstrates that narcissistic individuals release endorphins when receiving praise but not during reciprocal emotional exchanges 781 . They are biochemically rewarded for performance, not connection.

Validation and pain tolerance tell the story plainly. NPD individuals tolerate more pain immediately after receiving praise or achieving success—endogenous opioid release numbs physical discomfort 1285 . This may explain their ability to endure significant hardship pursuing narcissistic goals. The brain trades physical comfort for validation.

Cross-addiction between validation and substances is common and neurobiologically predictable. The same opioid system dysregulation that creates addiction to admiration increases vulnerability to substance addiction. Many individuals with NPD report using substances to manage the withdrawal from validation or to enhance the high of narcissistic success 397 . The brain does not distinguish between sources of opioid activation.

Opioid dysregulation in NPD traces back to early attachment. Secure infant attachment involves thousands of micro-moments of opioid release during positive caregiver interactions. The child who experiences inconsistent caregiving—sometimes flooded with attention, sometimes neglected—develops an opioid system requiring extreme stimulation to activate 949 . Ordinary pleasures of daily connection fail to register; only intense admiration activates reward.

Validation is more than psychological need—it is a neurochemical dependency as real as any addiction. The brain that should be rewarded by connection has been rewired to require admiration. Yet understanding this addiction at the molecular level offers hope. If validation operates through hijacked opioid systems, then treatments developed for addiction may help free individuals from the tyranny of needing constant validation. The chemical chains can be broken, though withdrawal will be real and difficult.

The Mood Regulators: Storms and Vigilance

The Serotonin System: Mood, Impulse Control, and the Fragile Self

Behind the grandiose facade, narcissists battle crippling mood swings, explosive rage, and crushing despair. The culprit: serotonin, the Mood Thread—or rather, its absence. The serotonergic system, originating in the raphe nuclei (the Mood Weavers) and projecting throughout the brain, regulates mood, impulse control, and social behaviour. Chronic disruption afflicts this system in narcissism.

Cerebrospinal fluid studies indicate that individuals with NPD have lower levels of 5-HIAA, the primary metabolite of serotonin, suggesting reduced serotonergic activity 793 . This hypofunctioning may contribute to the depression and impulsivity often seen in narcissistic individuals.

The serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT)—the “short” allele of which creates heightened emotional reactivity to stress—shows higher prevalence in individuals with NPD 220 . This genetic variation affects how quickly serotonin is cleared from synapses, influencing emotional regulation throughout life.

Pharmacological challenge studies using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) show that individuals with NPD have a blunted response to serotonergic enhancement 524 . While SSRIs typically increase emotional recognition and empathy, these effects are reduced in narcissistic individuals, suggesting deep alterations in serotonergic signalling pathways.

The interaction between serotonin and testosterone matters in NPD. High testosterone combined with low serotonin correlates with increased aggressive responses to ego threats 209 . The chemical cocktail of narcissistic rage has a specific neurotransmitter signature.

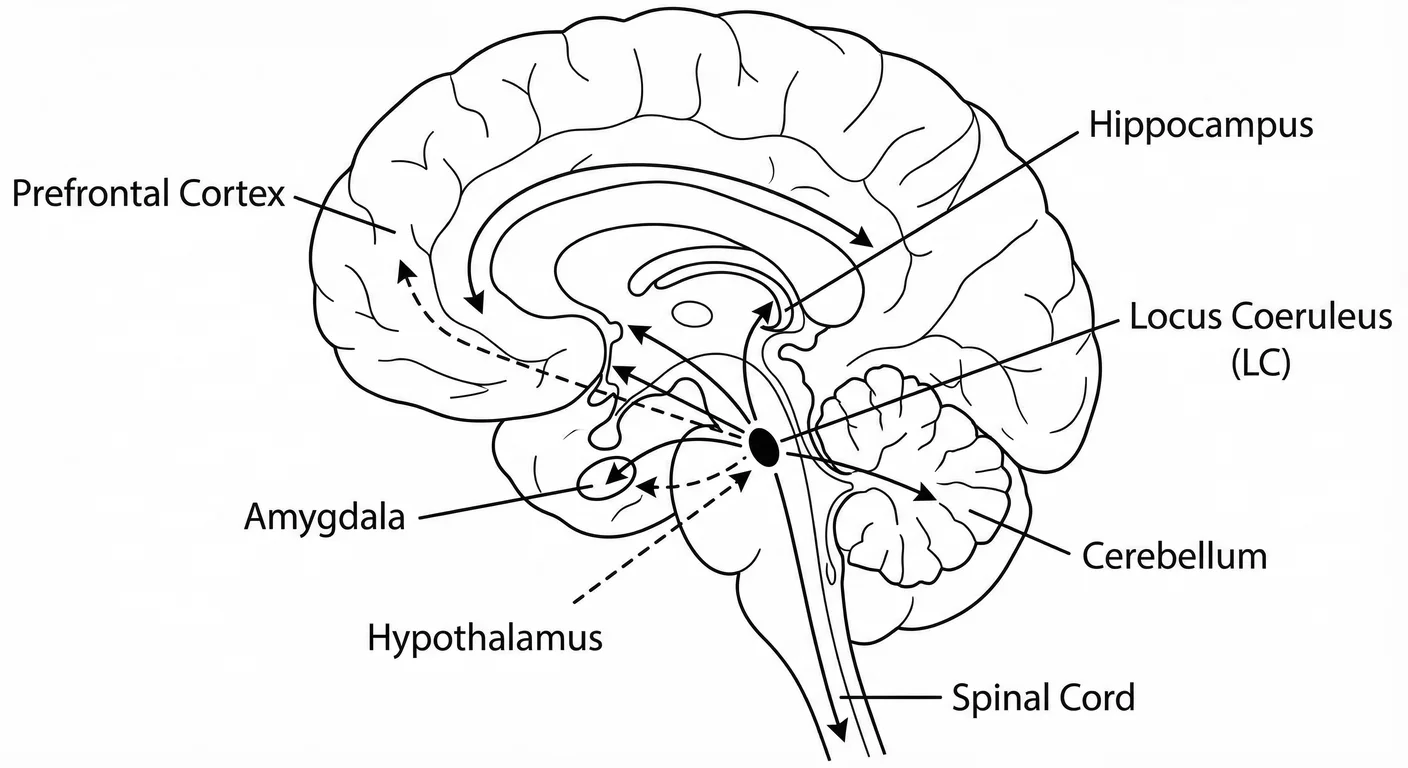

The Norepinephrine System: Arousal and the Hypervigilant Self

The narcissist is always scanning, always alert, always ready for the next threat to their carefully constructed image. This relentless vigilance originates in norepinephrine, the Alertness Chemical. The noradrenergic system, originating primarily in the locus coeruleus (the Sentry), modulates arousal and stress response. In the narcissistic brain, this system maintains chronic hypervigilance—scanning constantly for threats to self-esteem.

Salivary alpha-amylase, a biomarker of noradrenergic activity, shows elevated baseline levels in individuals with narcissistic traits, particularly vulnerable narcissism 484 . The body maintains physiological arousal even without external stressors.

The norepinephrine system shapes memory consolidation. Enhanced noradrenergic activity during emotional experiences strengthens memory formation, potentially explaining the vivid and persistent memories of narcissistic injuries 836 . The brain encodes wounds more deeply than ordinary experiences.

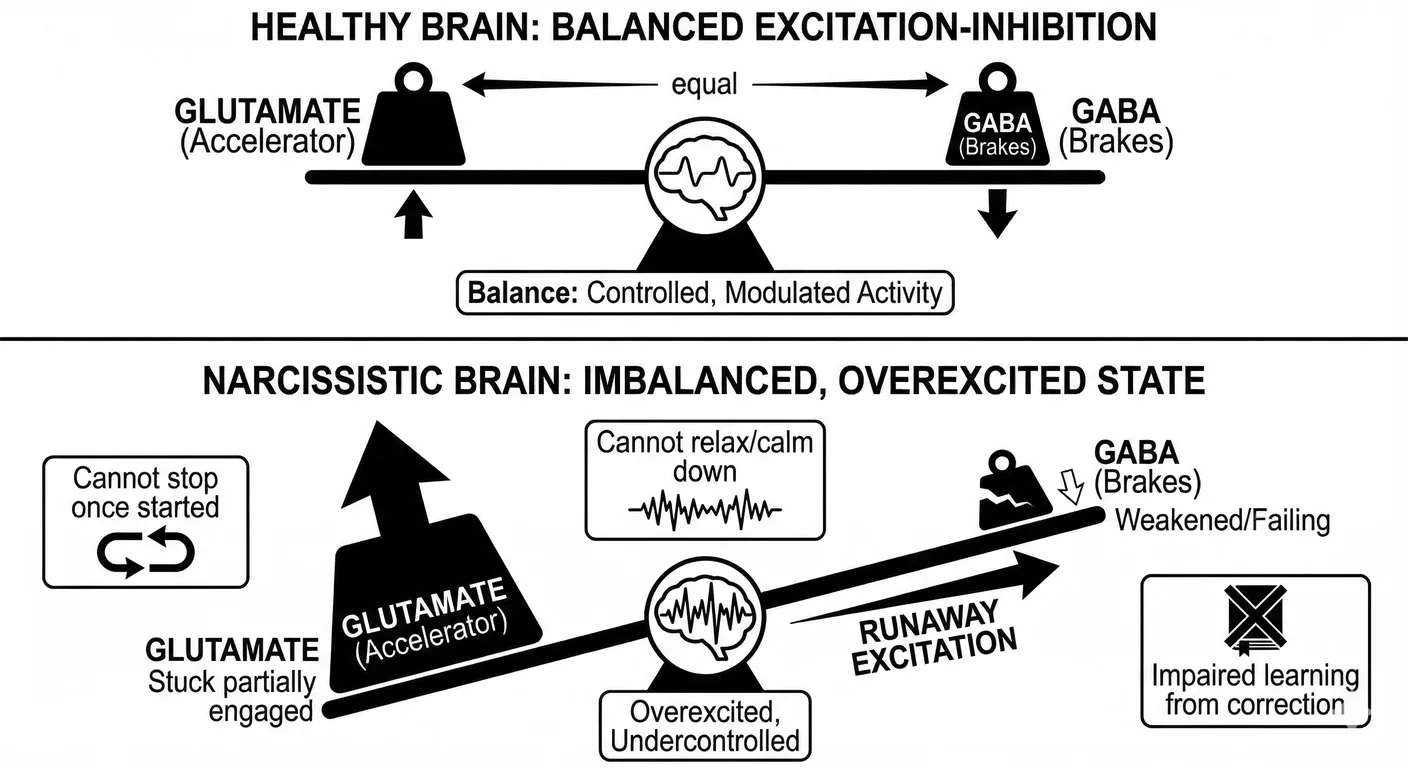

The Control Systems: Brakes and Accelerator

Two other brain chemicals explain critical narcissistic behaviours: the brain’s braking system and accelerator. GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) inhibits neural activity; glutamate excites it. They work in opposition.

The braking system calms excessive activation and enables controlled, measured responses. In the narcissistic brain, these brakes are failing 751 . The grandiose facade covers a brain in constant anxious activation 1017 .

The accelerator, meanwhile, is stuck partially engaged—creating restlessness and difficulty relaxing 1357 . The accelerator system is also responsible for learning, and in NPD it shows selective impairment. The brain encodes self-enhancing memories normally but struggles to encode corrective experiences 787 . They will learn praise more readily than criticism. The same plasticity mechanisms that should enable growth instead maintain pathological patterns.

The balance between accelerator and brakes is severely disrupted in NPD 1347 . The result: a brain that is simultaneously overexcited and undercontrolled—revving high but unable to steer.

You see it in their behaviour: they cannot stop once started—talking, raging, pursuing. The grandiose confidence conceals constant anxiety. Impulsive decisions are followed by elaborate rationalisation. They cannot let things go, even when continuing is clearly counterproductive. The neural mechanism for stopping is impaired. The constant anxiety beneath their confidence is real—the system is always running hot. The brakes are not merely weak; in some cases, they were never properly installed.

Time and the Temporal Self

How does the narcissistic brain actually experience time itself? Time is an experience the brain creates, moment by moment. The insula and basal ganglia construct our sense of duration. The Archivist (hippocampus) places events in sequence. The Throne Room (prefrontal cortex) projects into future and remembers the past (calling on the Archivist). And in the narcissistic brain all of these temporal mechanisms are distorted.

The narcissistic experience is deeply temporal: the past is a collection of wounds and triumphs obsessively revisited, the future a source of both grandiose fantasy and anxious dread, the present a fleeting moment barely inhabited before it becomes another memory to be distorted or defended against. Narcissists live everywhere except the present moment.

Temporal Processing: The When of Self

The insula (the Feeling Self) and basal ganglia (including the Reward Weigher), central to temporal processing, show altered activation in NPD during time perception tasks 1337 . Specifically, individuals with narcissistic traits show impaired duration estimation, typically underestimating the length of neutral experiences while overestimating the duration of self-relevant ones.

“Time flying” during validation and “dragging” during its absence have neurobiological roots. Dopaminergic activity in the substantia nigra pars compacta (the Rhythm Keeper), known to influence temporal perception, shows altered patterns in NPD 844 . High dopamine during supply compresses time; low dopamine during deprivation dilates it.

The posterior insula (the Body Listener) and right supramarginal gyrus (the Time Keeper), regions associated with the subjective experience of time passing, show reduced activation in narcissistic individuals during mindfulness tasks 373 . The narcissistic brain struggles to inhabit the present moment, always pulled towards past or future.

Circadian rhythm disruption, common in NPD, affects sleep, perception of time, and the experience of the present moment throughout the day 1045 . The narcissistic brain operates on its own temporal island, disconnected from the social rhythms that synchronise most human experience.

Memory Consolidation and the Construction of Self-Narrative

Profoundly altered encoding and consolidation build the narcissistic self from distorted memories.

Sleep plays a key role in memory consolidation, particularly slow-wave sleep—the deep restorative phase that consolidates declarative memory—and REM sleep, where vivid dreaming processes emotional experience and procedural memory. Polysomnographic studies demonstrate that individuals with NPD have reduced slow-wave sleep and altered REM patterns 1291 . The sleeping brain cannot properly process and integrate daily experiences, leading to fragmented self-narrative.

The replay of experiences during sleep, visible as coordinated hippocampal (the Archivist)-cortical activity, is biased in NPD. Self-enhancing experiences show enhanced replay, while interpersonal experiences show reduced replay 1328 . The sleeping brain rehearses grandiosity while forgetting connection.

NPD alters memory reconsolidation—whereby retrieved memories become temporarily malleable and can be modified 904 . Narcissistic individuals show enhanced reconsolidation of self-enhancing memories but impaired reconsolidation of corrective experiences. Each retrieval makes grandiose memories stronger and realistic assessments weaker.

“Rosy retrospection”—remembering experiences as better than they were—is amplified in NPD 875 . The vmPFC (the Royal Portrait Gallery) and hippocampus (the Archivist) connect more strongly during recall of past achievements, rewriting history to maintain grandiose self-perception.

The Bonding Chemistry: Connection Corrupted

Oxytocin (the Trust Hormone) and vasopressin (the Territory Hormone), closely related neuropeptides produced in the hypothalamus, orchestrate the neurobiology of bonding. These ancient neuropeptides, differing by only two amino acids, shape everything from maternal bonding to romantic attachment. In the narcissistic brain, these systems designed for connection have been corrupted, transformed into mechanisms for manipulation and territorial aggression.

Oxytocin (the Trust Hormone), produced in the paraventricular nucleus (the Bonding Chemist) and supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus, normally promotes trust and bonding. But in NPD, the oxytocin system shows paradoxical responses. Intranasal oxytocin administration, which typically increases prosocial behaviour, produces opposite effects in individuals with high narcissistic traits: increased aggression towards competitors, reduced cooperation with equals, and enhanced in-group favouritism that borders on paranoia 298 .

Genetic variations in the oxytocin receptor correlate with narcissistic traits—variants linked to reduced social sensitivity appear overrepresented 695 . The narcissistic brain may carry genetic programming for diminished oxytocin response, creating a biological barrier to normal bonding.

Blood and cerebrospinal fluid studies indicate that baseline oxytocin levels in NPD follow a bimodal distribution: grandiose narcissists show abnormally low baseline levels, while vulnerable narcissists show abnormally high levels 911 . Two different failures of the oxytocin system appear—one of deficiency, one of dysregulation. Neither achieves the moderate, responsive oxytocin levels needed for healthy attachment.

Oxytocin (the Trust Hormone) and dopamine (the Desire Chemical) interact to show how attachment systems become corrupted in NPD. Normally, oxytocin enhances dopamine release during social bonding, making connection inherently rewarding. In NPD, this coupling shifts: oxytocin enhances dopamine only when social interactions involve admiration or dominance 764 . Connection chemistry has been rewired to reward conquest rather than communion.

Vasopressin (the Territory Hormone), oxytocin’s closely related cousin, shows starker alterations in NPD. This hormone, central to pair bonding and territorial behaviour, is elevated in narcissistic individuals, particularly during perceived challenges to status or territory 188 . The vasopressin 1a receptor (V1aR), when overstimulated, produces the aggressive territoriality and mate-guarding behaviours that manifest as narcissistic possessiveness and jealousy.

The sexually dimorphic effects of these hormones may contribute to observed sex differences in NPD presentation, though research suggests these patterns partly reflect diagnostic bias: the DSM criteria emphasise grandiose features aligned with male socialisation, potentially underdiagnosing women whose narcissism manifests differently. 493 Testosterone amplifies vasopressin’s effects while dampening oxytocin’s; oestrogen enhances oxytocin sensitivity while moderating vasopressin’s. 212

Early life programming of oxytocin and vasopressin systems shapes NPD development. The infant who experiences inconsistent caregiving shows epigenetic modifications to oxytocin and vasopressin genes, particularly increased methylation that reduces their expression 227 . These epigenetic changes can persist throughout life and even be transmitted intergenerationally, creating biological legacies of disrupted attachment.

The oxytocin system shapes social memory too. Oxytocin normally enhances memory for faces and social information, helping us remember those who have shown us kindness. In NPD, this system preferentially encodes memories of admiration and slight. Brain imaging demonstrates that oxytocin administration enhances hippocampal (the Archivist) activation for self-relevant social memories but not for others’ experiences 503 . The chemistry of memory has been bent to narcissistic purposes.

Prairie voles, which form lifelong pair bonds mediated by oxytocin and vasopressin, have provided key insights into NPD. Voles with experimentally reduced oxytocin receptors in the nucleus accumbens (the Reward Hub) show “narcissistic” behaviours: reduced partner preference, increased aggression, and the pursuit of novel mates despite having a partner 1350 . The same neurochemical disruptions that prevent vole pair bonding may underlie the human narcissistic inability to form deep attachments.

Trauma bonding (explored in Chapter ) has a neurochemical basis in oxytocin-dopamine coupling. Intermittent reinforcement—alternating between kindness and cruelty—creates addiction-like attachment in victims by hijacking the same oxytocin-dopamine pathways that normally support healthy pair bonding 392 .

CD38—the Oxytocin Releaser, an enzyme essential for oxytocin secretion—shows reduced expression in NPD 608 . Social experience regulates this enzyme, which helps convert precursors into active oxytocin. The finding suggests that narcissistic individuals may have impaired capacity to produce oxytocin in response to social cues, creating a biological barrier to spontaneous connection.

Therapeutic interventions targeting these systems exist but require careful consideration. Oxytocin administration must be combined with therapy to avoid paradoxical aggression. Approaches that naturally boost oxytocin—such as massage and group singing—may prove safer than pharmacological intervention. 379 The corrupted chemistry of connection can potentially be restored, but the path requires more than simple hormone replacement. The narcissistic brain must relearn what connection means before its chemistry can properly support it.

Conclusion: Beyond the Hall of Mirrors

The narcissistic brain adapted neurobiologically to early environments where the self could not develop within consistent, attuned care. Every alteration—from dysregulated brainstem arousal to exhausted prefrontal control—embodies an attempt to survive a world that felt deeply unsafe for the emerging self.

The palace transformed into a hall of mirrors through necessity. The maze was built to protect. The very patterns that now cause suffering once served survival. Understanding this neurobiological reality helps us recognise the extensive work required for change.

The palace can be rebuilt. One can escape the maze. The mirrors can become windows. The self, so long defended and distorted, can finally come home to genuine connection with others and with its own authentic nature. But not through external intervention.

In those extremely rare cases where the narcissistic adult is not fully enclosed by the disorder, and they gain the insight and reach out themselves to reduce and overcome their traits actively, and if they then go through the long-term work required, over years, without external incentive—then and only then is there hope. And it is slight.

The science is clear: once the disorder is consolidated, there is no record of any self underneath it reaching out. We must not lose hope, but we must temper it with knowledge.