Before we ventured into the brain to understand the landscape and movement of the neurology, we looked for the causes of narcissism. This story has two sides, the subjective experience of the person set in their world, and the story of what is happening to their brain as they go from a pristine healthy child to the narcissistic adult. We can now see the main brain structures which are altered in narcissism—the hypervigilant system centred on the amygdala, and the shrunken hippocampus impairing memory, the lack of control due to the disconnected prefrontal cortex, the void of empathy caused by the stunted insula. But the question remains: how does the alteration happen? How can so many systems be affected?

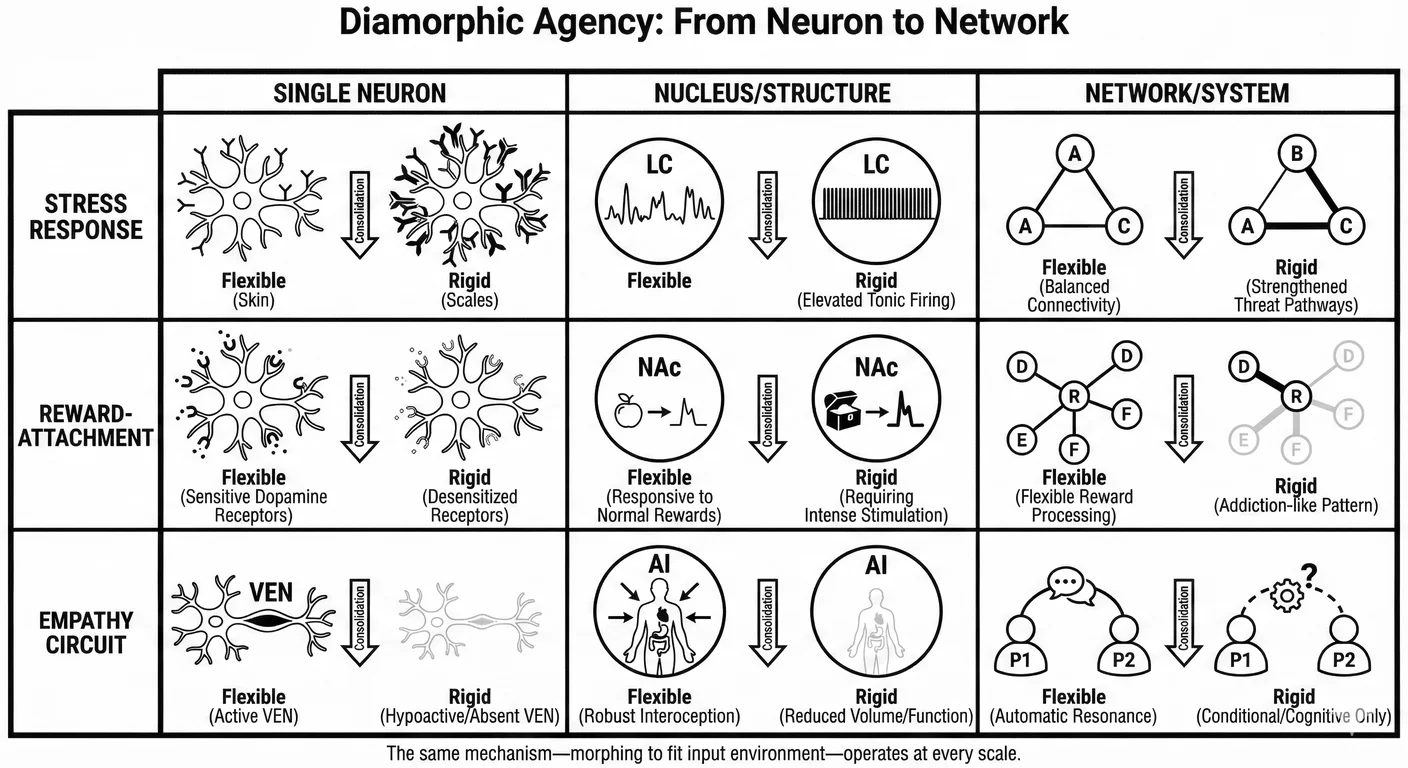

The answer lies in tracing how repeated attempts at selfhood reshape the child to survive their hostile environment. This happens through the rising levels of neural organisation. From single neurons adjusting their receptor profiles by downregulating, or ‘hardening’ to survive, up to coordinated networks reconfiguring their connectivity to focus on what works at the cost of all else. The same principle operates: systems reshape to fit available experience and these adaptations consolidate into increasingly rigid configurations. This is diamorphic agency, and it can feel abstract until we look directly at the systems which generate the narcissistic traits we see every day.

We can trace the ground-up development of three systems to show this:

The stress response system: how hypervigilance is built synapse by synapse, from the sentry (locus coeruleus) up through the amygdala-prefrontal balance and then to a brain-wide network reorganised around the central fixed belief of constant danger.

The reward-attachment system: how the child’s validation addiction is slowly hardwired into their dopamine circuits, forcing their reward centre (nucleus accumbens) to orient for intense stimulation, and finally up to global opioid systems learning that ordinary human connection will not satisfy.

The empathy circuit: we can show how their capacity to feel with others is selectively pruned while the capacity to understand them remains paradoxically intact—cognitive empathy sharpening as affective empathy withers.

The same mechanism appears at every scale as a neurobiological process. The infant adapting to fit the narcissistic parent ends up reflecting at the psychological level what their neurons have already been doing at the unconscious, cellular level.

The Neuron to Neuron Conversation

To understand how a child like Maisie breaks under pressure, we must first understand a fundamental principle that makes us who we are.

A neural system does not just “process” its environment; it physically reconfigures itself to match it. It has to do this to survive in the most literal and existential sense. This principle—what we earlier called diamorphic agency—operates with fractal precision. It occurs in the shifting functional connectivity of brain structures like the insula, in the collective firing patterns of a nucleus, and, essentially, in the solitary architecture of each single neuron.

The silencing of a child begins here. The relational reshaping that occurs in the home is grounded in the cell itself.

The Decision Engine

The neuron is the fundamental signaling unit of the nervous system. But to understand Maisie it is best understood as a biological decision engine. It is designed to resolve order from chaos. It does this by converting a variety of signals into a single decision—whether or not to fire.

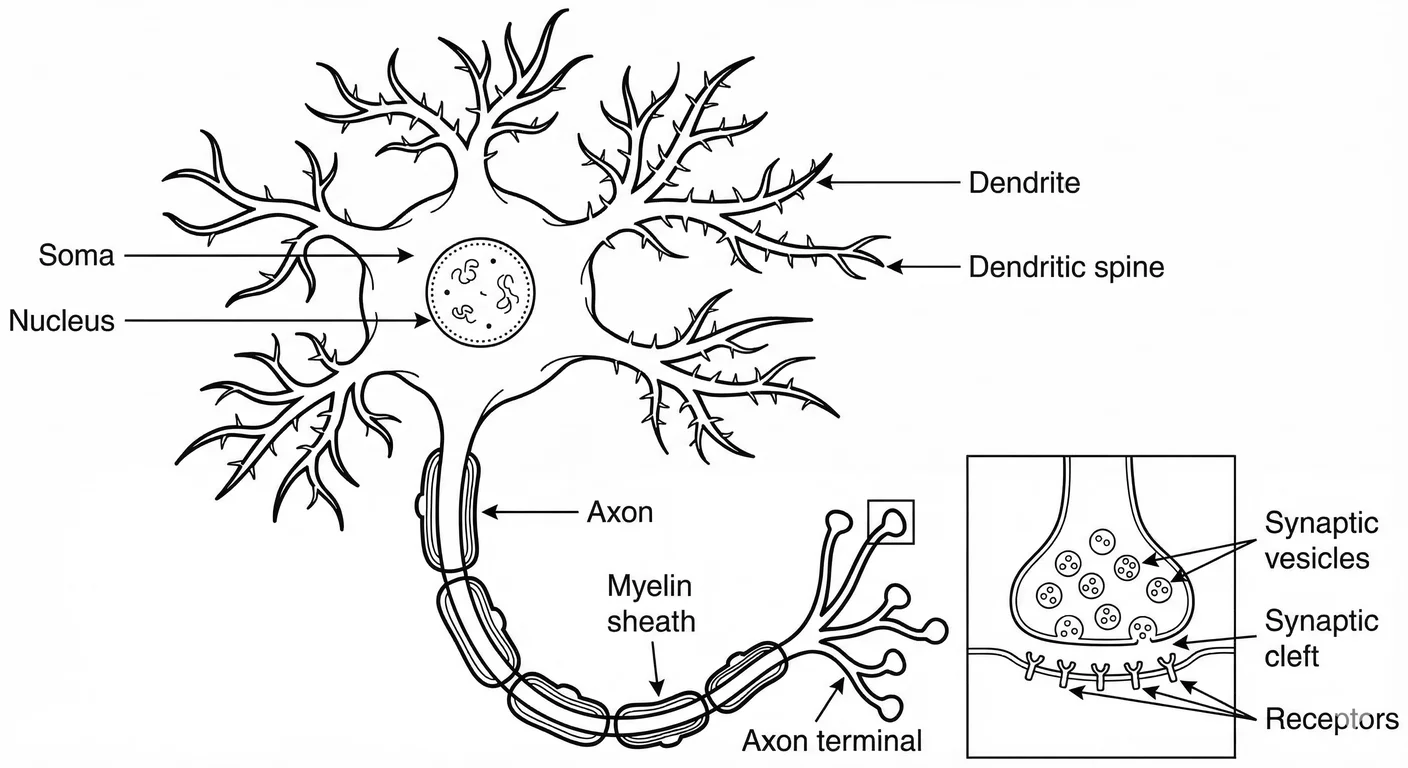

Consider the neuron’s three primary parts not as anatomy, but as distinct stages in decision: Receiving, Integrating, and Transmitting.

**The Dendritic Arbor: The Interface **

The dendrites are the neuron’s sensory array—a sprawling, branching canopy that reaches out to intercept signals from thousands of sister cells. This “dendritic arbor” is the physical manifestation of the neuron’s receptivity.

Each branch is studded with dendritic spines— little molecular gateways that determine how much of the outside world is allowed in. This architecture is not fixed. In a safe environment, the arbor is lush and complex, maximizing connection. In a hostile one, it retreats. The neuron prunes its own branches, reducing its surface area to minimise the “noise” of a chaotic environment.

**The Soma: The Integrator **

All incoming signals flow into the soma, which comprises the main cell body of the neuron. While the soma houses the metabolic machinery of life (the nucleus, the mitochondria), its functional role is that of a switch.

The soma performs a summation of every excitatory and inhibitory signal it receives from every sensor in its array of dendrites. It has a threshold required for firing its own signal. Over time this threshold shifts as the soma recalibrates, becoming either trigger-happy (towards hypervigilance) or nearly comatose (towards dissociation). It is here the cell’s decision to respond is made.

The Axon: The Commitment

If the soma’s threshold is met the signal moves to the axon. This is the transmission line—a single, unidirectional highway that carries the neuron’s signal to the rest of the network.

This is an electrochemical wave that travels from the soma down the axon to the synaptic terminals. This triggers the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft where two neurons meet. These molecules bind to receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, either exciting it (increasing the probability that it will fire) or inhibiting it (decreasing that probability). 1014

Once a signal enters the axon, there is no turning back; it is an all-or-nothing commitment to communicate. The axon terminates in synaptic boutons, releasing chemical messengers across the cleft to bind with the next neuron, starting the cycle for its sister cell.

The Scale of the Shift

Synaptic transmission is not a fixed mechanical process. The strength of a synapse along with how much neurotransmitter is released and how many receptors are available to receive in combination with how strongly the postsynaptic neuron responds is dynamically regulated based on the specific history of activity at that synapse. 434 This is the foundation of learning and memory—and of diamorphic agency at the cellular level.

If this recalibration happened in a single cell, it would be inconsequential. But the brain is a galaxy of 86 billion such engines. Each neuron connects to as many as 10,000 others, creating an adaptive network of roughly 100 trillion connections.

When we say a child “adapts” to a narcissist, we are describing a cascading update across this network of 100 trillion tiny switches. The entire system—from the receptor profile of a single dendrite to the architecture of the self—morphs to fit the shape of experience.

The Norepinephrine Neuron: A Specific Example

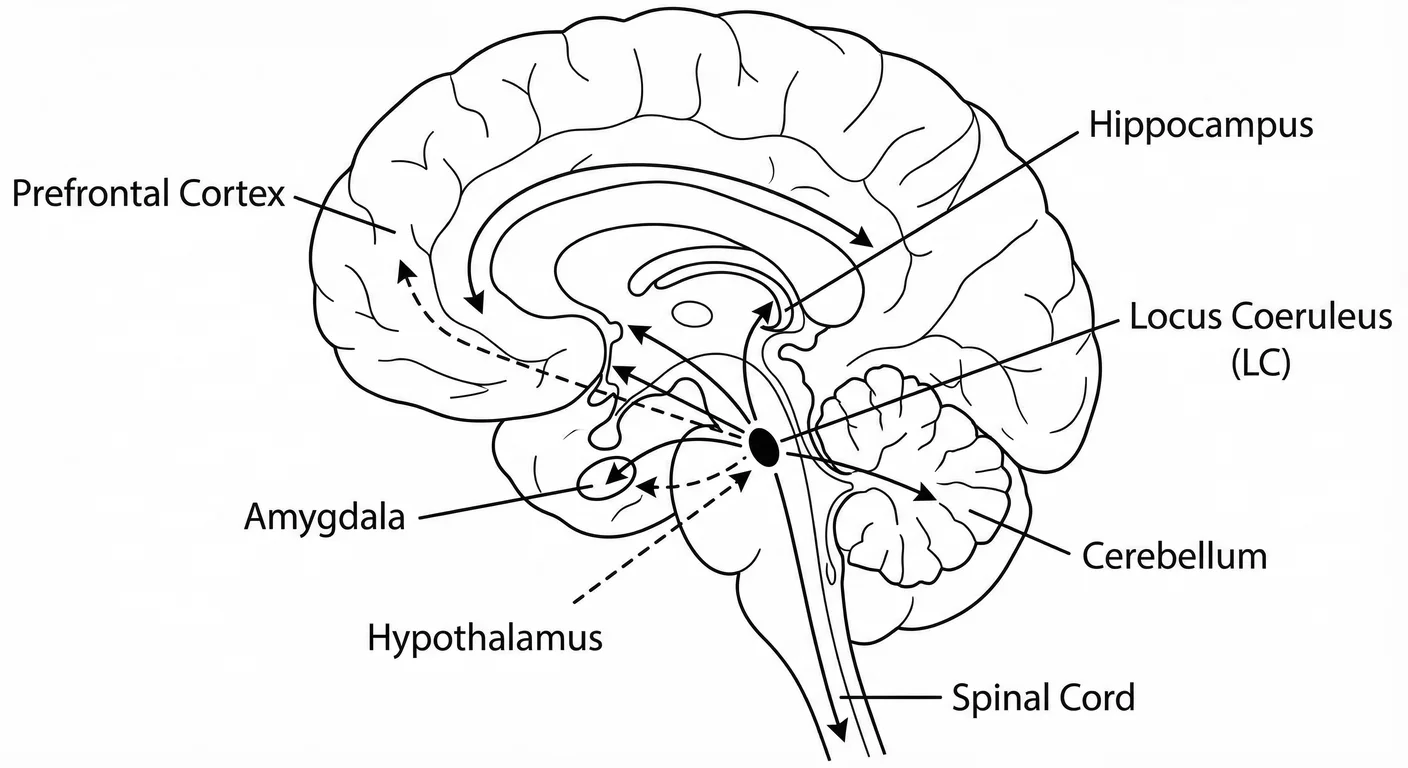

Let us understand in detail how this works for the stress and vigilance system; we will focus on the noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus which we know as the Sentry. Its role is to rouse the brain when sensory experience warrants it and does this via cells that produce and release noradrenaline—also called norepinephrine, which is the neurotransmitter of arousal and vigilance.

The Sentry is special because the neurons comprising it have dendrites which extend far into the surrounding brain. They receive input from multiple regions including the prefrontal cortex (throne room), amygdala (alarm bell), and hypothalamus. Its axon also projects widely. A single LC neuron may send branches to the cortex, hippocampus (the Archivist), amygdala, and spinal cord simultaneously. This allows it to affect arousal across the entire nervous system.

Under normal conditions, LC neurons fire in two modes: 54

Tonic mode: A steady baseline firing rate of 1–3 Hz (Hz is Hertz, frequency in number of times per second) during waking, decreasing during sleep. This tonic activity maintains general arousal and readiness to respond. We can think of it as the steady background hum of awareness.

Phasic mode: Brief bursts of high-frequency firing (8–10 Hz for 100–200 milliseconds) in response to experience marked as relevant, also known as salient stimuli. This can be events such as unexpected sounds, a sudden awareness of novel objects, or anything which requires our voluntary attention. We can notice the shape of our awareness change when this happens, forming a direction. These phasic bursts therefore orient us towards the particular stimulus and enhance our sensory processing. They help us to focus and concentrate on the new thing in our senses.

The balance between tonic and phasic firing establishes healthy functioning. Our best thinking happens at moderate tonic levels with strong phasic responses. This is where we are alert enough to respond but not so hyperaroused that we cannot focus. 54 Too little tonic activity makes us drowsy and inattentive; too much produces anxiety and distractibility. 1062 Too weak phasic responses mean we miss important stimuli; phasic responses that are too easily triggered mean attending to everything, which is tantamount to attending to nothing.

This balance is not genetically fixed, either; it is calibrated by our experience. 889

This means any individual neuron cannot actually choose its configuration. It must adapt to the input patterns it receives. When those patterns are continual and consistent our adaptations consolidate and become the neuron’s new baseline. This is diamorphic agency at the cellular level.

Receptor Regulation: Adapting the Cell Surface

The postsynaptic membrane, where signals jump from one neuron to the next, is also adaptive. The number, type, and sensitivity of receptors on the cell surface actually grow or diminish based on input history. 114

Upregulation: When a neuron receives insufficient input of a particular neurotransmitter it will increase the number of receptors for that particular transmitter on its surface. This will make the neuron more sensitive and so able to respond to smaller amounts of that signal.

Downregulation: Conversely, when a neuron receives excessive input it will drop receptor numbers and so make itself less sensitive. This has the benefit of protecting the cell from overstimulation but at the cost of reducing its responsiveness.

Receptor trafficking: The receptors themselves can be rapidly inserted into or removed from the cell membrane at the synapse. This allows moment-to-moment adjustments in sensitivity. Over longer timescales, our baseline number of receptors can also change through altered gene expression. 114

Now let us go back to Maisie as a child. Consider her norepinephrine neuron receiving chronic (unrelenting) stress signals. Cortisol (her stress hormone) and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) act on her receptors within her Sentry and so increase firing rates. If this situation is sustained, by for example her mother continuing to stress her child, the neuron does not passively receive it—it physically adapts:

This happens through the following mechanisms:

-

Alpha-2 adrenergic autoreceptors (which normally inhibit noradrenaline release through negative feedback) may downregulate, removing the brake on firing 1267

-

Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) receptors may upregulate, increasing sensitivity to stress signals 1031

-

The neuron’s intrinsic excitability may increase through changes in ion channel expression 114

The result is that Maisie’s neurobiology is physically altered. Each neuron affected has morphed to fit an environment of what it experiences as chronic stress. It isn’t just in the child’s mind, it’s an objectively measurable physical fact. Each neuron will now fire more readily, respond more intensely to stress signals, and will in future have reduced capacity for self-inhibition. This is not pathology in the way we usually think of it: it is an adaptation to the primary caregiver causing threat or fear or misery. It means Maisie will be ever more watchful because she will not want bad things to happen like they did before, she will without realising it, be ever more watchful, ever more alert.

Dendritic Remodelling: Morphing the Input Structure

The dendritic tree present in all neurons is itself adaptive. Holtmaat in 2009 discovered that dendrites will extend and retract, branch and prune based on activity patterns. 567

Activity-dependent growth: Dendrites grow towards sources of consistent and patterned input. Synapses frequently activated will then strengthen and stabilise; the spines that house them physically enlarge. 637 The neuron is literally reaching towards the input it receives.

Pruning of unused connections: Dendrites receiving little input retract. This means that synapses which are rarely activated will weaken and eventually disappear. 974 The neuron therefore withdraws from input sources that are unavailable.

Spine shape changes: Dendritic spines exist on a continuum from thin, movable ‘learning spines’ to thick, stable ‘memory spines.’ Experience physically shifts this distribution. 635

When we look at the chronic stress Maisie experiences, dendritic remodelling displays characteristic patterns. Neurons in the hippocampus (the Archivist) show dendritic retraction. They have shortened branches, and fewer spines, and so reduced capacity to receive input. 834 Neurons in the amygdala (the Alarm Bell) show the opposite—dendritic expansion, with increased spine density, and so enhanced capacity to receive threat-related input. 1283

Brain regions are affected by stress in rich and varied ways. Different regions morph in different directions, each adapting with its own strategy aligned to its functional role in a threatening environment. The Archivist shrinks because detailed memory encoding is a comparative luxury and reliving recent or past negative experience will interfere with the child’s survival; the Alarm Bell expands because threat detection is likewise now more important for Maisie’s survival. The various characters we met in prior chapters expand and diminish their roles in the growing maze, strengthen and harden some relationships with each other, and diminish or dismiss others. This is childhood trauma played out as damage across the neural landscape.

Epigenetics: Adapting Gene Expression

For Maisie the damage reaches all the way down to her genetics and how they work in each cell. Research on epigenetic mechanisms, which are modifications to DNA or its associated proteins that affect gene activity without changing the genetic sequence now shows experience will also alter what the neuron produces. 842

DNA methylation: The addition of methyl groups to DNA typically silences gene expression. Early life stress can increase methylation of genes encoding stress-buffering receptors (like the glucocorticoid receptor) and so permanently reduces their expression. 1308

Histone modification: DNA is wound around histone proteins; modifications to these proteins affect how accessible genes are for transcription, which is essential for them to produce the proteins the cell needs to work properly. Stress alters histone acetylation and methylation patterns in ways that can persist for years. 139 If the genes are not accessible, they cannot provide the healthy RNA necessary to regulate stress across the system.

Non-coding RNA: Small RNA molecules can regulate gene expression even after they have been created from healthy genes. Stress also alters microRNA profiles in ways that affect neuronal function. 594

These epigenetic changes are the mechanism by which experience becomes ground into our biology. The neuron that experiences chronic stress does not just respond to that stress—it becomes a chronically stressed neuron with associated altered gene expression that persists even when the stressor is removed. It is altered in nature. The adaptation has consolidated. The stress has become structural.

Synthesis: The Neuron as Dyadic Partner

We can now see how Maisie’s neuron expresses diamorphic agency:

-

The neuron does not choose its configuration. It responds to input patterns according to molecular rules.

-

The neuron morphs to fit the input space available. Through receptor regulation, dendritic remodelling, and epigenetic modification the neuron reshapes itself to match the input environment it receives.

-

The morphing consolidates over time. Acute changes in receptor density can reverse when input normalizes; continual changes may persist indefinitely in gene expression.

-

The neuron shows the skin/scales distinction. A neuron that receives balanced, varied input develops flexible responsiveness (skin). It integrates and adapts to experience. However one that receives chronic, extreme input develops rigid, defensive configurations (scales)—either hyper-responsive and reactive or desensitised like armour, but it is no longer as flexibly adaptive.

Maisie, in her bed, is dreaming while adapting her proto-self to fit the available relational space. Doing at the psychological level what her neurons are doing at the cellular level. The mechanism is the same; only the scale differs.

The Stress System

From Neuron to Nucleus

Neural function emerges from the coordinated activity of neuronal populations. The next level of diamorphic agency operates at the nucleus—the cluster of neurons sharing common function.

Anatomy and Organisation of the Sentry

The Sentry (Latin name: locus coeruleus or ‘blue spot,’ is named for its pigmented appearance in the tissue) is a small nucleus in the brain stem housing 15,000–30,000 neurons in each hemisphere in humans. 54 Despite this modest cell count we know LC neurons reach almost every region of the brain and spinal cord. This makes the LC the primary source of noradrenaline, the arousal neurotransmitter, for the entire central nervous system.

The Sentry has some differentiation, with neurons projecting to different brain regions being partially segregated within the LC 1110 but there is also extensive interconnection. LC neurons are (electrotonically) coupled through gap junctions. This lets them synchronise their firing. 54 When one LC neuron fires, its neighbours tend to fire as well, creating coordinated volleys of noradrenaline release across the brain.

The LC receives input from multiple sources:

-

Prefrontal cortex: Top-down signals indicating task demands and cognitive goals

-

Amygdala and bed nucleus of stria terminalis: These provide threat and anxiety signals

-

Hypothalamus: Homeostatic state (hunger, temperature, sleep/wake phases)

-

Periaqueductal grey: Pain and defensive behaviour signals

-

Nucleus paragigantocellularis: Cardiovascular and autonomic state

These inputs converge on the LC and it integrates them to determine the appropriate level of arousal for current conditions. 111 It not only watches, but determines how watchful we are.

Normal Function: The Adaptive Gain Controller

Aston-Jones and Cohen put forward an influential theory of LC function: the adaptive gain hypothesis. 54 According to this theory, the LC modulates the ‘gain’ of neural processing throughout the brain—in plain terms it calibrates how strongly neurons respond to their inputs.

Low gain (low tonic): Neurons respond weakly to input; the system is in an exploratory mode. It samples broadly from the environment but holds back strong commitment to any particular stimulus or task.

High gain (high tonic): Neurons respond strongly to input; the system is in exploitation mode. It is focused intensely on the current task or stimulus and actively filtering out distractions.

Optimal gain: Moderate tonic with strong phasic responses allows the system to focus when needed while remaining responsive to unexpected important stimuli.

The healthy LC continuously adjusts its firing to maintain optimal gain for current task demands. During a tricky mental task LC tonic activity typically increases to enhance focus. When the task is complete, LC activity decreases to allow broader environmental sampling. When a truly novel or important stimulus occurs a phasic burst will reorient attention. 54

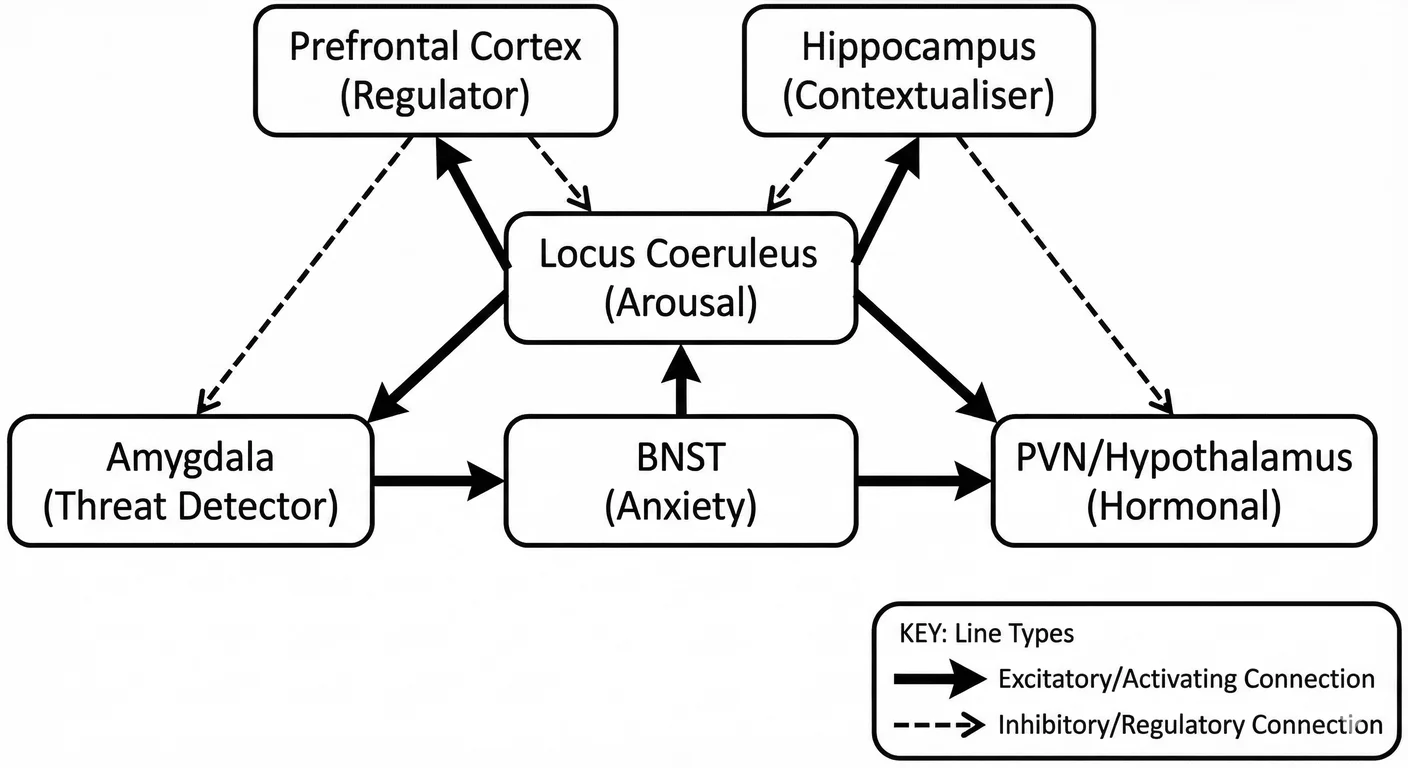

This dynamic regulation depends on the LC receiving accurate information about task demands (from prefrontal cortex), threat levels (from amygdala), and internal state (from hypothalamus). When this information is reliable and the environment is predictable, the healthy LC will calibrate appropriately.

But when the environment is continually stressful, like for Maisie, it sees that threat information is constant. This is especially true when the executive prefrontal cortex is itself under-developed due to early adversity. The LC simply does not receive the information it needs to calibrate normally. It must therefore adapt to the information it has to hand. Maisie doesn’t know the wider world is different than her world with her mother, her whole reality depends on a caregiver who doesn’t see her fully or meet her needs.

How the Nucleus Morphs: Collective Adaptation

As her Sentry grows to meet her world, we see emergent properties—collective behaviours that arise from the coordination of many neurons. The morphing of the LC as a whole is more than the sum of its individual neurons’ adaptations.

Elevated baseline firing: Chronic stress increases the average tonic firing rate across the LC population. 1267 This is not just the sum of individual neuron adaptations—it reflects changes in the network properties of the nucleus, including altered gap junction coupling that synchronizes the elevated firing. 604

Reduced phasic responsivity: When tonic firing is chronically elevated, her phasic responses diminish—the signal-to-noise ratio decreases. 1267 The nucleus as a whole loses the capacity for sharp, discriminative responses to salient stimuli. Everything becomes relevant; therefore nothing is. This has profound implications for her learning and behaviour throughout her life.

Altered input sensitivity: The nucleus develops changed sensitivity to its various inputs. Cortisol hormone related inputs from the amygdala become more powerful; prefrontal executive inputs become less so. 1031 Emotions take precedence over reason and inhibitory behaviour in an attempt to identify and avert threats. The LC nucleus is morphing as a whole to prioritise threat signals over her cognitive control signals.

Structural changes: Chronic stress can alter the physical structure of the LC, including changes in her Sentry’s dendritic morphology and altered expression of synthetic enzymes. 1368

In a nutshell, the infant of a narcissistic parent experiences chronic unpredictability. The parent is sometimes present, sometimes absent; sometimes warm, sometimes cold; sometimes attentive, sometimes rageful. 785 The infant cannot predict when threat will occur. The only adaptive strategy is constant vigilance.

The Stress Response System: From Nucleus to Coordinated Network

We know the Sentry does not operate in isolation. It is part of a distributed network—the stress response system—that coordinates multiple structures to detect and respond to threat. At this systems level, we see diamorphic agency operating through altered connectivity and functional coordination.

Anatomy of the Stress Response Network

The stress response system comprises several interconnected structures: 1261

Locus coeruleus: The noradrenergic hub, providing arousal signals throughout the brain.

Amygdala: The threat detector, particularly the basolateral amygdala (BLA) for threat learning and the central amygdala (CeA) for coordinating defensive responses.

Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN): The hormonal effector, releasing CRH to activate the HPA axis and trigger cortisol release from the adrenal glands.

Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST): The anxiety generator, mediating sustained responses to diffuse or uncertain threats.

Prefrontal cortex: The regulator, particularly the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), providing top-down inhibition of stress responses.

Hippocampus: The contextualiser, providing memory-based information about whether current circumstances match past threat situations.

These structures are densely interconnected through both direct synaptic connections and indirect hormonal signals (cortisol from the adrenal glands acts on receptors throughout the network). 834

Normal Function: Coordinated Threat Response

In a well-calibrated stress response system, these structures coordinate to produce adaptive responses to genuine threats while avoiding excessive activation to non-threats. 834

Threat detection: The amygdala receives sensory input and rapidly evaluates it for threat relevance. If threat is detected, the amygdala activates both the LC (for immediate arousal) and the PVN (for hormonal response).

Arousal and attention: LC activation increases norepinephrine throughout the brain, enhancing sensory processing, focusing attention on the threat, and preparing motor systems for action.

Hormonal cascade: PVN activation triggers CRH release, which stimulates ACTH from the pituitary, which stimulates cortisol from the adrenal glands. Cortisol mobilises energy resources and modulates immune function.

Contextualisation: The hippocampus provides contextual information—is this situation similar to past threats? Is escape possible? This information modulates amygdala activity.

Regulation and termination: The prefrontal cortex, particularly vmPFC, provides top-down inhibition of the amygdala once the threat has passed. Cortisol also provides negative feedback, inhibiting further CRH release. The system returns to baseline.

The key feature of healthy stress response is termination. The system activates when needed and deactivates when the threat resolves. This requires accurate threat detection, effective regulatory mechanisms, and intact negative feedback loops. 834

How the System Morphs: Network-Level Adaptation

When we examine the stress response system as a coordinated network, we see adaptations that emerge from the interactions between structures—adaptations that cannot be understood by examining any single structure in isolation.

Altered connectivity strengths: Chronic stress changes the functional connectivity between network nodes. The connection from amygdala to LC strengthens; the connection from prefrontal cortex to amygdala weakens. 47 The network has restructured to prioritise threat signals over regulatory signals.

Shifted balance points: The balance between activation and inhibition shifts towards activation. The amygdala becomes hyperresponsive; the prefrontal cortex becomes hyporesponsive; the hippocampus loses volume and regulatory capacity. 834 The entire network has morphed towards a threat-oriented configuration.

Impaired negative feedback: Chronic cortisol exposure downregulates glucocorticoid receptors in the memory (hippocampus) and executive (prefrontal cortex) areas of the brain, in turn reducing the effectiveness of negative feedback. 767 The whole brain begins to lose its capacity to terminate stress responses. This means over time that activation becomes self-perpetuating.

Sensitisation: Repeated stress does not produce habituation but instead sensitisation—every follow-on stress source produces a larger response. 767 The network learns again and again that threats are common and severe; it learns to respond accordingly.

Developmental programming: Early life stress produces major network-level changes. The developing brain has enhanced plasticity, which means it is especially vulnerable to stress-induced reorganisation. 1219 The child’s neural network is conditioned during those critical periods when it is most malleable.

The Morphed Network in Narcissistic Architecture

The full pathway runs from early relational trauma to adult narcissistic brain architecture:

Infancy (0–18 months): The infant of the narcissistic parent experiences chronic unpredictability. 1097 The amygdala, detecting inconsistent caregiving as threat, activates repeatedly. The LC shifts towards elevated tonic firing. The PVN releases chronic low-level CRH. The hippocampus, bathed in cortisol, fails to develop normal volume and connectivity. 767 The prefrontal cortex, lacking adequate co-regulation from the caregiver, does not develop strong connections to the amygdala. 1097

Early childhood (18 months–5 years): The network adaptations consolidate. 842 The amygdala shows dendritic expansion; the hippocampus shows dendritic retraction. 834 Epigenetic changes lock in altered stress responsivity. 1308 The child’s baseline arousal elevates; their capacity for regulation diminishes. The network has morphed to fit an environment of chronic threat.

Later childhood and adolescence: Further developmental changes occur against this altered baseline. The adolescent pruning process, which normally eliminates unused connections, operates on a network that was abnormally configured from the start. 1219 The abnormal configuration is strengthened rather than corrected.

Adulthood: The adult narcissist carries this morphed network. 1219 Their amygdala is hyperresponsive to ego threat. Their LC maintains chronic hypervigilance. Their prefrontal cortex cannot effectively regulate emotional responses. 47 Their hippocampus fragments memory, preserving injuries while losing ordinary experience. 834 Their entire stress response system operates as if threat is constant and severe—because during the critical period of its formation, threat was constant and severe.

Network Diamorphic Agency: The System as Dyadic Partner

At the network level, we see diamorphic agency operating through emergent properties that transcend individual structures:

-

The network does not choose its configuration. No structure ‘decides’ to become hyperresponsive or hyporesponsive. The network adapts to input patterns according to the rules of synaptic plasticity and hormonal feedback.

-

The network morphs to fit the input space available. When threat signals dominate and regulatory signals are weak, the network restructures to process threat efficiently, at the cost of flexible regulation.

-

The morphing consolidates through multiple mechanisms: Changed synaptic strengths, altered receptor densities, epigenetic modifications, and structural remodelling all contribute to consolidation. Early-life morphing is particularly persistent.

-

The network shows the skin/scales distinction. A network that develops under conditions of predictable safety and reliable co-regulation develops flexible responsiveness—it can activate to genuine threats and deactivate when threats resolve (skin). A network that develops under chronic threat develops rigid hyperactivation—it cannot distinguish genuine threats from minor challenges, cannot terminate stress responses, cannot return to baseline (scales).

The narcissistic adult’s vigilant brain is not a metaphor. It is a stress response network that morphed to fit the relational environment of early childhood, consolidating adaptations that persist decades after the original environment has changed. The scales are real—they are altered connectivity patterns, changed receptor densities, epigenetic marks on DNA. They were grown layer by layer, synapse by synapse, in response to an environment that demanded defence.

The mechanism of this growth is identical at every scale: the cell, the nucleus, and the network all demonstrate diamorphic agency—adaptation to available input space, consolidation of adaptations over time, increasing rigidity as flexible responsiveness is sacrificed for defensive preparation.

Implications: From Mechanism to Meaning

Understanding diamorphic agency at the neural level changes how we think about narcissistic development and its remediation.

Responsibility and Causation

These neural mechanisms operate entirely below conscious awareness. The infant cannot choose whether their LC will develop elevated tonic firing. The child cannot decide whether their amygdala-prefrontal connectivity will strengthen or weaken. The adolescent cannot select which synapses will be pruned. These processes occur according to molecular and cellular rules that have nothing to do with intention, choice, or moral responsibility.

This does not eliminate responsibility in adulthood—the adult with a morphed stress response system still makes choices about behaviour. But it reframes the question of responsibility. The narcissist’s vigilant brain is not a character flaw that could have been avoided through better choices. It is the predictable outcome of early environmental input operating on neural tissue according to the same rules that govern all brain development.

The Difficulty of Change

Neural morphing consolidates through multiple overlapping mechanisms. Reversing these changes would require:

-

Restoring normal receptor densities on thousands of neurons

-

Rebuilding retracted dendrites in the hippocampus

-

Pruning expanded dendrites in the amygdala

-

Reversing epigenetic modifications at multiple gene loci

-

Strengthening weakened prefrontal-amygdala connections

-

Re-establishing functional negative feedback loops

This is not impossible—some neuroplasticity continues throughout life—but it is extremely difficult. Plasticity diminishes significantly with age; the adult brain retains only a fraction of the malleability it possessed during the critical periods of childhood. 543 The mechanisms that consolidated the original morphing must be engaged in reverse, and they work slowly. Years of therapeutic work may be required to produce modest changes in network function.

This explains why therapy for narcissistic personality disorder is so difficult and outcomes so uncertain. The therapist is not merely changing beliefs or behaviours—they are attempting to rewire a stress response network that was configured during the period of maximum plasticity and has been reinforced for decades since.

The Primacy of Prevention

If adult remediation is difficult, prevention becomes the priority. These neural mechanisms suggest clear intervention points:

Prenatal: Reducing maternal stress during pregnancy may protect fetal brain development from cortisol-mediated alterations.

Infancy (0–18 months): Ensuring consistent, responsive caregiving during the period when attachment patterns and stress response systems are being established is maximally protective.

Early childhood (18 months–5 years): Providing stable, predictable environments and teaching co-regulation skills can prevent further consolidation of maladaptive patterns. 816

Adolescence: The second window of enhanced plasticity offers opportunities for intervention, though on a network already partially configured by earlier experience.

The goal throughout: provide the input environment that shapes neural development towards flexible integration (skin) rather than rigid defence (scales).

The Validation of Subjective Experience

Diamorphic agency at the neural level validates the subjective experience of those affected. The narcissist who reports that they cannot stop their vigilance, cannot relax their defences, cannot trust even when they want to—they are reporting accurately on the state of their nervous system. The victim of narcissistic abuse who describes feeling deeply altered by the experience—they too are reporting accurately. Chronic exposure to narcissistic behaviour can induce the same network-level changes, albeit typically less severe than those occurring during developmental critical periods.

The mechanism is real. The suffering is real. The difficulty of change is real. Understanding diamorphic agency at the neural level does not minimise any of this—it explains it, grounds it in biology, and points towards both the necessity and the challenge of intervention.

The stress response system—from single neuron to coordinated network—demonstrates diamorphic agency at every scale. Two additional pathways illuminate the full picture: the attachment-reward system (explaining the narcissist’s addiction to validation) and the empathy circuit (explaining their characteristic deficit in emotional resonance).

The Reward System and Attachment

Narcissism is not only about hypervigilance to threat—it is equally about the desperate, addictive pursuit of validation. The reward system provides a second example of how narcissistic traits develop into pathology.

The reward system evolved to motivate approach behaviour—to make us seek out food, water, warmth, mates, and social connection. In humans, this system has been strengthened by attachment. The infant’s experience of caregiving is not just comforting; it is profoundly rewarding in the precise neurobiological sense. Dopamine and endogenous opioids are released during positive social interaction, producing both pleasure for us and the motivation to seek more. 592

When early attachment is disrupted our reward system does not stop growing—being fundamental to our survival it instead develops abnormally. Because it must adapt to an environment where ordinary connection does not trigger reward, it reshapes itself so only intense validation (or admiration) can activate the neural circuits designed for social pleasure. This is the foundation of narcissistic supply: a reward system hardwired over time to require intense stimulation because ordinary reliable comfort never occurred during its formation.

The Dopamine Neuron: The Seeker

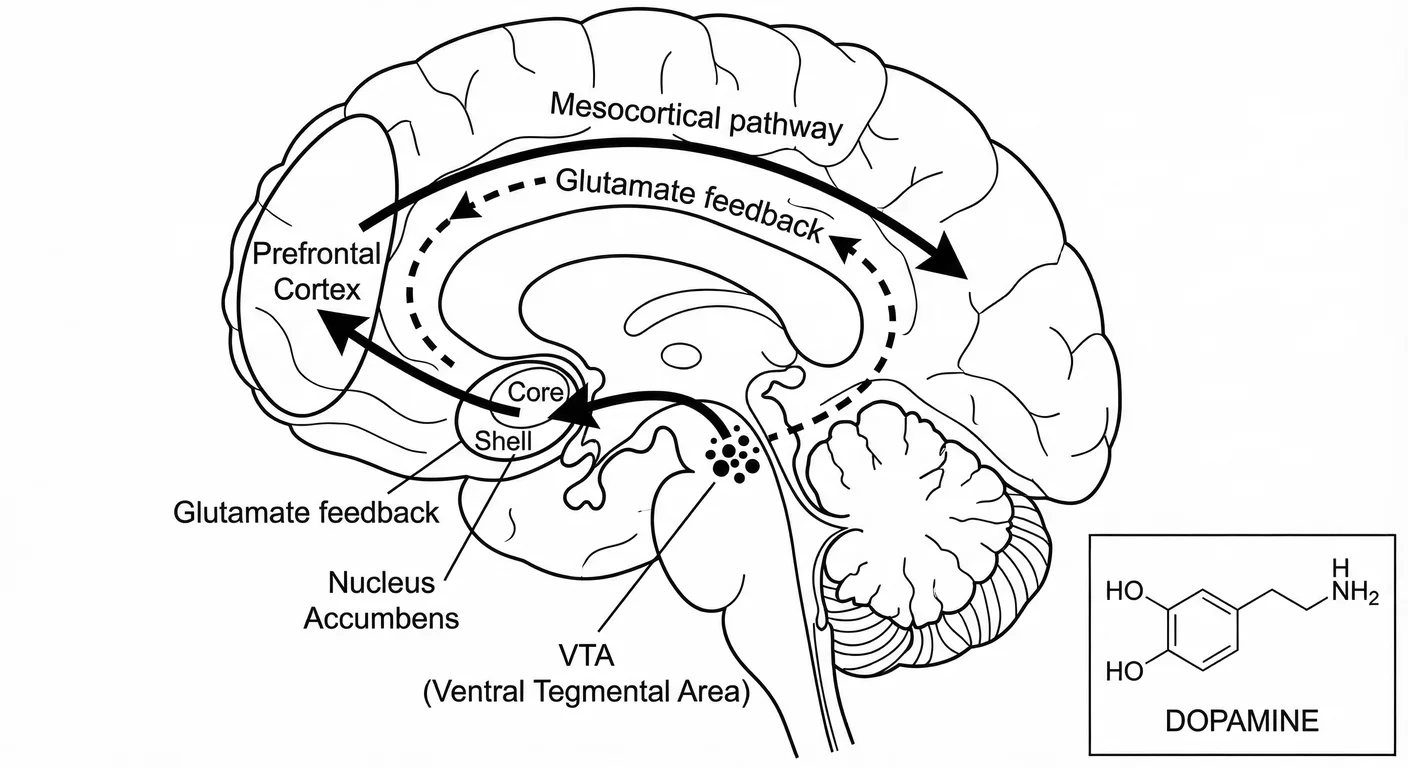

Where the Sentry’s noradrenaline neurons ask “Is this dangerous?” the dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) ask “Is this worth pursuing?” They are Seekers rather than Sentries—their job is not vigilance but motivation. They project to the Reward Centre (nucleus accumbens), the Throne Room (prefrontal cortex), and the Alarm Bell (amygdala), coordinating the brain’s approach behaviour. 702

The key to understanding how dopamine shapes narcissism lies not in the neuron’s architecture—which follows the same principles we saw in the stress system—but in what these neurons encode.

Reward Prediction: The Slot Machine in the Brain

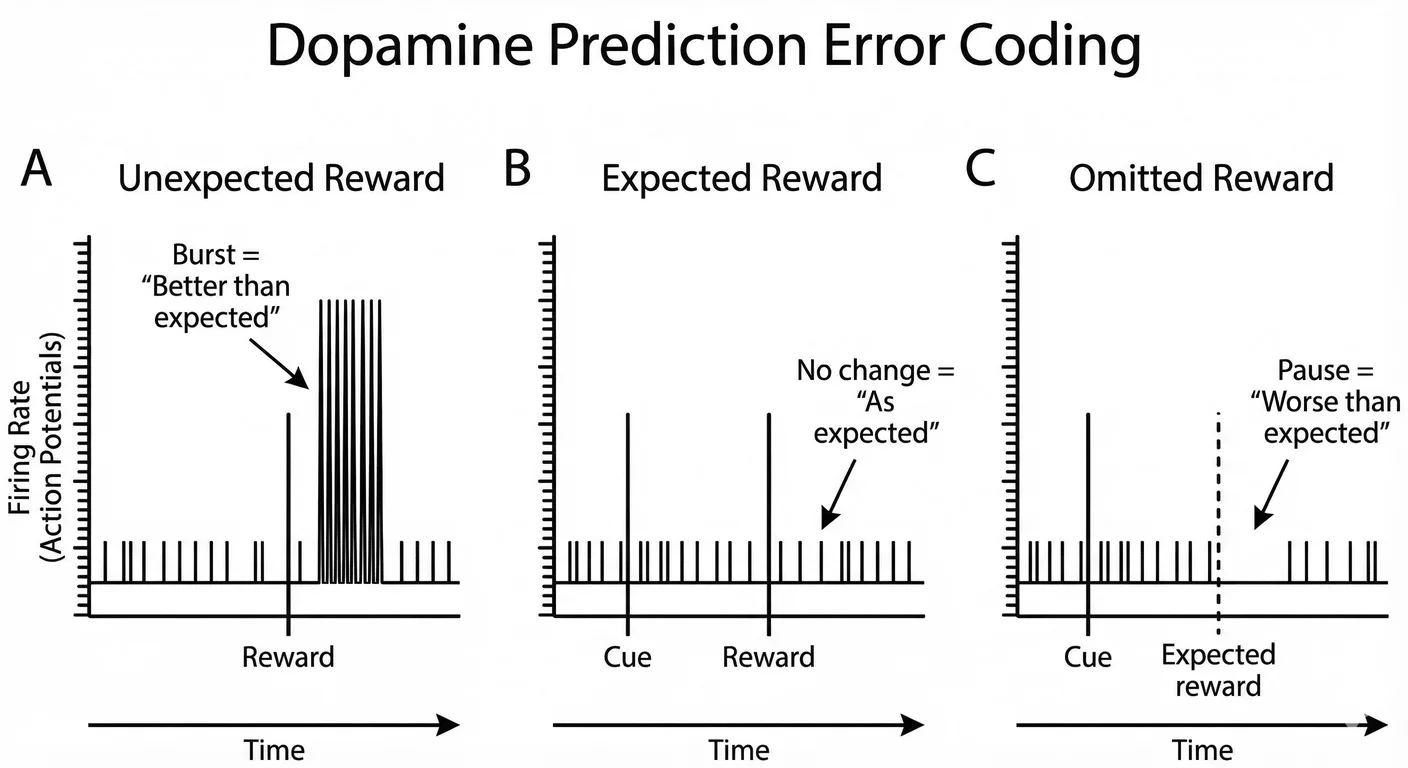

Wolfram Schultz pushed our understanding of dopamine forward by discovering reward prediction error signalling. 1102 Rather than simply responding to rewards, dopamine neurons encode the difference between expected and received rewards:

Unexpected reward: When a reward occurs that was not predicted, dopamine neurons fire a burst of action potentials. This burst signal indicates ‘better than expected’ and strengthens whatever behaviours preceded the reward.

Expected reward: When a predicted reward occurs as expected, dopamine neurons show little change in firing. The reward was already anticipated; there is nothing new to learn.

Omitted reward: When an expected reward fails to occur, dopamine neurons actively pause their firing, briefly falling below baseline. This pause signal indicates ‘worse than expected’ and weakens the behaviours that led to disappointment.

The fact of prediction error coding allows dopamine to function as a teaching signal. Behaviours that lead to better-than-expected outcomes are reinforced; behaviours that lead to worse-than-expected outcomes are weakened. Over time we learn to predict rewards accurately and to perform behaviours that maximise reward. 1103 This is fundamental to almost all human behaviour and motivation.

Dopamine does not encode pleasure, but motivation—the drive to pursue rewards. The distinction matters: we can find something pleasurable without being motivated to seek it (as in anhedonia), or we can be intensely motivated to seek something that no longer provides pleasure (as in addiction). Dopamine drives the seeking, not the satisfaction. 112

Social Reward: Attachment Meets Dopamine

For us, a highly social species like humans, social stimuli are among the most powerful rewards. Consider the sight of a caregiver’s face, or even the sound of a friendly voice and the touch of a comforting hand. To our brains they all activate dopamine neurons in ways parallel to food, or water, or other primary rewards. 1034

For a human child, like Maisie, or even Laura when she was young, social connection is not optional—it is survival. The infant who is motivated to seek closeness to caregivers, and then to elicit caregiving behaviour through cries and coos and smiles is far more likely to survive than the infant who is indifferent to social contact. We all start off courageous and socially bold. Nature has wired the dopamine system to treat attachment figures as rewarding. 592 217

Neuroimaging studies in the past two decades confirm this. Viewing images of our romantic partner lights up our VTA dopamine neurons. 49 Similarly, receiving social approval from those who matter to us lights up our Reward Centre (nucleus accumbens). 597 Even viewing images of our own child activates the reward system in those of us who are parents. 1193 This is why we carry photos of our loved ones in our wallets or purses. And have them on our desk at work. Social connection is not just pleasant—it is fundamentally rewarding and motivating in the same inner pathways which also process food, sex, and drugs.

The Tolerance Trap: How the Reward Neuron Goes Numb

The narcissistic parent is a slot machine.

Sometimes Maisie’s mother is warm and present. Sometimes she is cold and distant. Sometimes extraordinary effort produces reward; sometimes it produces nothing, or punishment. The child cannot predict which pull of the lever will pay out. This is the worst possible environment for a developing reward system—not consistent deprivation (which produces one kind of adaptation) but unpredictable reward, which produces addiction. 31

Consider what happens to Maisie’s dopamine neurons. They are trying to build a prediction model, but the parent’s responses follow no learnable pattern. Prediction errors are constant and large. The system cannot stabilise. And so it adapts the only way it can: by going numb.

Downregulation: Growing Scales on the Reward System

The primary mechanism is receptor downregulation—the same defensive response we saw in the stress system. When dopamine signals are chaotic and unpredictable, target neurons reduce their D2 receptors, the receptors most responsible for experiencing reward as pleasurable. 1280 Fewer receptors means less response to the same signal. The neuron is protecting itself from the whiplash of constant prediction errors.

This is the cellular basis of tolerance. With fewer D2 receptors, ordinary levels of dopamine no longer register as rewarding. The child needs more—more intense validation, more dramatic confirmation of worth—to achieve the same reward system activation that another child gets from a simple hug. 69

The adaptation makes sense as defence. But defence has costs. The neuron that has grown scales against unpredictable reward has also lost sensitivity to reliable, ordinary connection. It has traded flexibility for protection.

The Epigenetic Lock

These changes consolidate through epigenetic modification. The genes encoding D2 receptors show altered methylation patterns in adults with histories of childhood adversity—the receptor reduction is not just functional but written into gene expression. 916 The adaptation that began as protection becomes permanent architecture. The child’s reward system has been calibrated, at the level of DNA regulation, for a world where ordinary connection does not satisfy.

This is why the seventeen-year-old Maisie, checking her phone for the fourteenth like, feels the warmth spark and fade. Her reward system was configured in childhood to require intense, dramatic validation. The steady appreciation of a friend, the quiet pride of accomplishment—these ordinary rewards fall below a threshold that was set years ago, in a Norwich kitchen, by a mother whose responses followed no predictable pattern.

The addiction to narcissistic supply begins here: in D2 receptors that were downregulated to survive a slot-machine parent, and in epigenetic marks that locked the adaptation into place.

The Reward Highway and the Broken Brake

The individual dopamine neuron is part of a larger system: the mesolimbic pathway, which we can think of as the brain’s ‘reward highway.’ This highway runs from the VTA (where Seeker neurons live) to the nucleus accumbens (the Reward Centre), with a crucial feedback loop through the prefrontal cortex (the Throne Room). 398

The key insight for understanding narcissism is the relationship between wanting and control:

The Highway (VTA → NAc): This pathway generates ‘wanting’—the motivational energy that makes stimuli attractive and worth pursuing. When dopamine floods the nucleus accumbens, we feel driven to seek. Animals with depleted NAc dopamine can still enjoy rewards delivered directly to them, but they lack the motivation to pursue those rewards. 112

The Brake (PFC → VTA): The prefrontal cortex provides top-down control, allowing cognitive evaluation to modulate reward-seeking. This is what lets us decide that the third glass of wine isn’t worth it, that the risky investment is a bad idea, that the affair would destroy our marriage. The brake allows us to want something and choose not to pursue it.

In disrupted development, the highway strengthens while the brake weakens. The nucleus accumbens becomes hypersensitive to intense reward cues (like admiration) while the prefrontal cortex loses its capacity to regulate the pursuit. 965 The result is compulsive reward-seeking that cognitive insight cannot override—the defining feature of addiction.

This is why the seventeen-year-old Maisie, in the earlier vignette, knows she should feel satisfied with 127 likes and a Regional Art Prize—but cannot stop checking her phone anyway. Her prefrontal cortex can see what is happening. But the brake was weakened during development, and the highway runs at full throttle. Insight without control is torture.

The Chase and the Hug: Why Wanting Replaces Liking

There is a crucial distinction hidden in the reward system that explains much of narcissistic suffering. Dopamine mediates wanting—the motivational drive to pursue. But the brain has a separate system for liking—the actual pleasure of having obtained what we sought. This is the endogenous opioid system. 112

Think of it this way:

Dopamine = The Chase. The excitement of pursuit, the thrill of the hunt, the anticipation of reward. This is what drives Maisie to post the photo and check her phone. It is wanting, seeking, craving.

Opioids = The Hug. The warm satisfaction of arrival, the contentment of being held, the peace of enough. This is what should follow—the landing after the flight, the meal after the hunger. It is liking, savouring, resting.

In healthy attachment, both systems develop together. The infant who is held reliably learns that the chase ends in the hug. Their opioid system—particularly the mu-opioid receptors that mediate social bonding—becomes sensitised to ordinary connection. 949 A parent’s presence, a friend’s warmth, a partner’s touch all trigger opioid release. The wanting leads to liking, and the liking satisfies the wanting.

But when early attachment is disrupted, the systems develop out of balance. The opioid system, starved of reliable connection, fails to calibrate properly. Mu-opioid receptors are downregulated; the capacity for social pleasure atrophies. 781 Meanwhile, the unpredictable parent keeps triggering dopamine—sometimes reward comes, sometimes it doesn’t—and the wanting system becomes hyperactive.

The result is a reward architecture built for pursuit but not for satisfaction. The narcissist becomes addicted to the Chase because they cannot metabolise the Hug. They can want intensely, seek compulsively, crave desperately—but when they obtain what they sought, the opioid system cannot convert the achievement into lasting pleasure. The warmth sparks and fades. They must chase again.

This is why the twenty-two-year-old Laura, holding her Founder’s Prize, feels almost nothing. Her dopamine system drove her to pursue it. But her opioid system, configured in a Norwich attic where hugs were unreliable, cannot convert the victory into satisfaction. She is already scanning for the next fix before the current one has cooled.

The Integrated Reward-Attachment System in Narcissistic Development

Disrupted attachment shapes the complete reward system, producing the characteristic narcissistic pattern of validation addiction.

The Developmental Sequence

Early infancy (0–6 months): During the first months of life, evidence suggests the reward system begins learning the contingencies of social interaction. 1097 When caregiving is consistent, the system likely learns: ‘Social cues reliably predict reward.’ Dopamine neurons develop appropriate prediction models; opioid release becomes associated with ordinary caregiving experiences. 841

When caregiving is inconsistent, the system learns differently: ‘Social cues do not reliably predict reward.’ The infant cannot predict when the caregiver will be warm versus cold, present versus absent, attuned versus preoccupied. Dopamine prediction errors are frequent and large—sometimes caregiving occurs unexpectedly (positive error), sometimes expected caregiving fails to occur (negative error). The system cannot stabilise around a reliable prediction. 767

Later infancy (6–18 months): The system begins consolidating its learning. 1097 In healthy development, the infant has learned that their bids for connection generally produce response. The reward system is calibrated for a social world that is, on average, responsive. Dopamine and opioid systems are sensitised to ordinary social cues. 592

In disrupted development, the infant has learned that only certain bids—those that successfully capture the narcissistic parent’s attention—produce response. Perhaps extreme distress works when ordinary fussing does not. Perhaps exceptional performance works when ordinary behaviour does not. The reward system calibrates to these contingencies, becoming sensitised to extreme stimuli while becoming desensitised to ordinary ones. 841

Toddlerhood and early childhood (18 months–5 years): The patterns consolidate through receptor regulation, synaptic plasticity, and epigenetic modification. 1308 The child’s reward system now requires intense stimulation to achieve reward activation. Ordinary praise does not register; only effusive admiration exceeds the threshold. Ordinary affection does not satisfy; only dramatic displays of devotion trigger opioid release. 1280

The child has morphed their reward system to fit the relational environment. That environment taught them that ordinary is worthless, that only the exceptional is rewarded. This lesson is now encoded in receptor densities, firing patterns, and gene expression. 1219

The Adult Narcissistic Reward System

By adulthood, the morphed reward system produces characteristic patterns:

Tolerance: Like any addiction, the narcissistic pursuit of validation shows tolerance. The dose that worked yesterday no longer suffices today. The admiration that once produced satisfaction now barely registers. Ever-greater validation is required to achieve the same reward system activation.

Withdrawal: When validation is unavailable, the narcissist experiences genuine withdrawal—dysphoria, restlessness, irritability, a desperate need for supply. This is not merely psychological—it reflects reduced dopamine and opioid activity in reward circuits, the same neurochemical signature as drug withdrawal.

Compulsive seeking: Despite negative consequences, the narcissist continues to seek validation. Relationships are damaged, careers are sabotaged, opportunities are squandered—but the compulsion continues. The reward system drives behaviour even when higher cognitive functions recognise the cost.

Anhedonia for ordinary pleasures: The narcissist may show reduced pleasure from ordinary activities and relationships. The reward system, calibrated for intense stimulation, finds ordinary life unrewarding. Only validation activates the morphed circuits.

The Skin/Scales Distinction in the Reward System

The reward system shows the same skin/scales distinction we observed in the stress response system. The healthy reward system develops flexible responsiveness to ordinary connection (skin); the disrupted reward system develops rigid calibration for intense stimulation (scales). The narcissist’s scales protect against constant disappointment but close off the capacity for ordinary social pleasure.

Implications for Understanding Narcissistic Validation Seeking

Validation Seeking as Addiction

This neural account shows validation seeking as genuine addiction: 1281

-

Compulsive use despite negative consequences: The narcissist pursues validation even when it damages relationships and opportunities

-

Tolerance: Increasing amounts are required for the same effect

-

Withdrawal: Characteristic negative state when supply is unavailable

-

Neurobiological substrate: Altered dopamine and opioid function in reward circuits

-

Conditioned cues: Environmental triggers that provoke craving

This is not metaphorical addiction. It is addiction in the precise neurobiological sense, involving the same circuits and mechanisms as substance addiction. The narcissist is not merely ‘psychologically dependent’ on validation—they are neurochemically dependent on it.

The Impossibility of Satisfaction

The morphed reward system explains why the narcissist can never be satisfied. The problem is not that they receive insufficient validation—many narcissists receive enormous amounts. The problem is that their reward system has been calibrated to a threshold that ordinary validation cannot exceed.

The tolerance mechanism means that any validation that does exceed threshold becomes the new baseline. Yesterday’s triumph is today’s expectation. The narcissist is on a hedonic treadmill with the dial turned to maximum—running ever faster yet never arriving at satisfaction.

This is neurobiologically determined. The receptor densities, the firing patterns, the epigenetic modifications—all conspire to make satisfaction impossible. No amount of external validation can compensate for a reward system that has morphed to require more than any environment can sustainably provide.

The Tragedy of the Disrupted Bond

Perhaps the deepest tragedy is what has been lost: the capacity for ordinary social pleasure. The healthy individual can sit with a friend and feel contentment. They can receive a compliment and feel genuinely pleased. They can be held by a loved one and feel the opioid-mediated warmth of connection.

The narcissist has lost access to these ordinary pleasures. Their reward system, morphed to survive an environment of disrupted attachment, no longer responds to the stimuli that should trigger reward. They are surrounded by potential sources of connection yet neurobiologically unable to experience them as rewarding.

They did not choose this. Their dopamine neurons adapted to the input they received. Their opioid system calibrated to the contingencies of early caregiving. The scales that now prevent ordinary pleasure were grown layer by layer, receptor by receptor, in response to an environment that offered only the exceptional or nothing.

Understanding this does not excuse harmful behaviour. But it reframes our understanding of what narcissism is: not merely a character flaw or a moral failing, but a neurobiological adaptation that has trapped its bearer in a reward system that can never be satisfied by what ordinary life offers.

The same principle—adaptation to available input space, consolidation over time, increasing rigidity as flexibility is sacrificed—operates from single dopamine neuron to integrated mesolimbic-opioid network. The narcissist’s addiction to validation is written in altered receptor densities, changed firing patterns, and epigenetic modifications—the molecular signature of a reward system that morphed to fit an environment of disrupted attachment.

The Empathy Circuit: Diamorphic Agency and the Capacity to Feel With Others

The third pathway is the neural circuitry underlying empathy—the capacity to perceive, share, and respond to others’ emotional states.

The narcissistic empathy deficit is perhaps the most consequential feature of the disorder. It is what allows narcissists to exploit, manipulate, and discard without apparent remorse. It is what makes intimacy with them so wounding—the sense that one is seen as object rather than subject, as supply rather than person. Understanding how this deficit arises at the neural level illuminates both its origins and its limits.

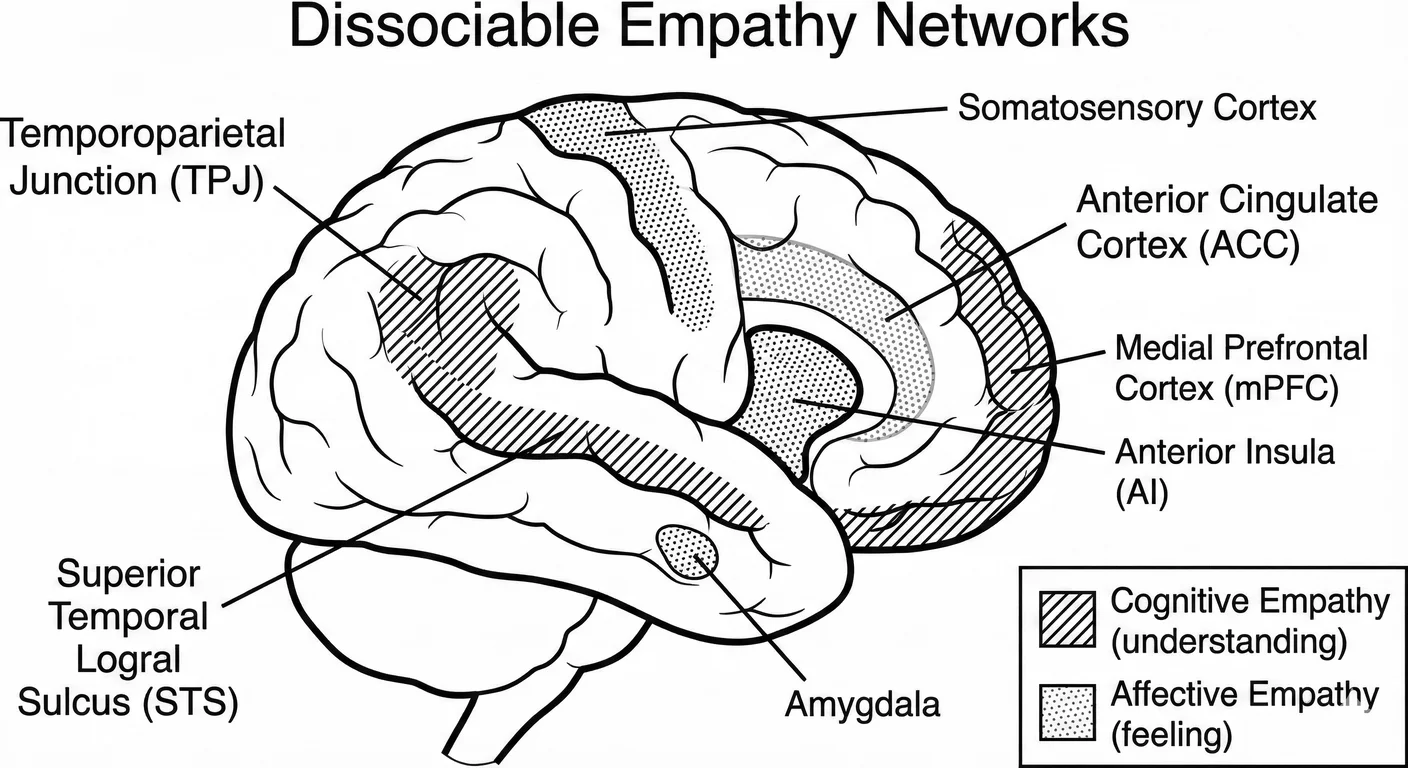

The picture that emerges is not of empathy’s absence but of its distortion. The narcissist typically retains cognitive empathy—the ability to understand what others think and feel, to read social cues, to predict behaviour. What is impaired is affective empathy—the capacity to feel what others feel, to experience their distress as distressing, their joy as joyful. 1037 82 363 This selective impairment has its basis in the differential morphing of distinct empathy circuits during development.

Two Systems of Empathy: Cognition and Affect

Before tracing the neural architecture, we must distinguish two distinct empathic capacities: 1122

Cognitive empathy—also called mentalising, theory of mind, or perspective-taking—is the capacity to represent others’ mental states, to understand what they believe, intend, desire, or feel. This is a cold, computational process. One can have accurate cognitive empathy while feeling nothing.

Affective empathy—also called emotional empathy or empathic concern—is the capacity to share others’ emotional states, to feel distress when witnessing suffering, joy when witnessing happiness. This is a hot, embodied process. It involves the body, produces physiological changes, and motivates prosocial action.

Both capacities are necessary for full empathic function. Cognitive empathy without affective empathy produces the psychopath who can read minds but feels nothing. Affective empathy without cognitive empathy produces overwhelming emotional contagion without understanding. Healthy empathy integrates both: accurate understanding of others’ states coupled with appropriate emotional resonance. 296

These two capacities depend on partially distinct neural circuits and show different patterns of vulnerability to developmental disruption. In narcissism, cognitive empathy is typically preserved (sometimes even enhanced, as manipulation requires accurate mind-reading) while affective empathy is impaired. 832 This pattern reflects the differential morphing of the circuits underlying each capacity.

The Cells That Learn to Feel

Empathy has its own specialised neurons, and they develop during exactly the years when attachment is being formed.

Von Economo neurons (VENs) are found in the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex—the regions most critical for affective empathy. Unlike most brain cells, VENs are scarce at birth and appear to increase substantially during the first years of life, based largely on comparative studies across species. 23 This postnatal development suggests they may be shaped by early experience in ways that prenatal neurons are not. The child who is felt with may develop more robust VEN populations than the child who is ignored or misread.

Mirror neurons may provide one mechanism for learning to feel—though this remains debated among neuroscientists. When the infant smiles and the mother smiles back, the infant’s brain appears to learn connections between the motor experience of smiling and the visual perception of smiling. 660 Over thousands of such exchanges, the infant builds a library of mappings: this is what joy looks like, this is what sadness feels like, this is how my inner state connects to what I see on your face.

Whatever the precise neural mechanism, mirror-like responses are not automatic. They develop through being mirrored. 1236

When the narcissistic parent does not mirror—because they are preoccupied with their own states, or mirror only selectively (responding to expressions that serve their needs while ignoring others)—the infant cannot learn accurate mappings. Their mirror systems develop poorly calibrated, less automatically activated, or active only under specific conditions. 539

This is the cellular origin of selective empathy. The adult narcissist can feel with others—the mirror systems function—but they feel selectively. They mirror those who provide supply while failing to mirror those who do not. The selectivity began in infancy, in the selective mirroring they themselves received. We learn to feel by being felt with. 1236 When no one feels with us, we learn something else instead.

The Translator Goes Silent

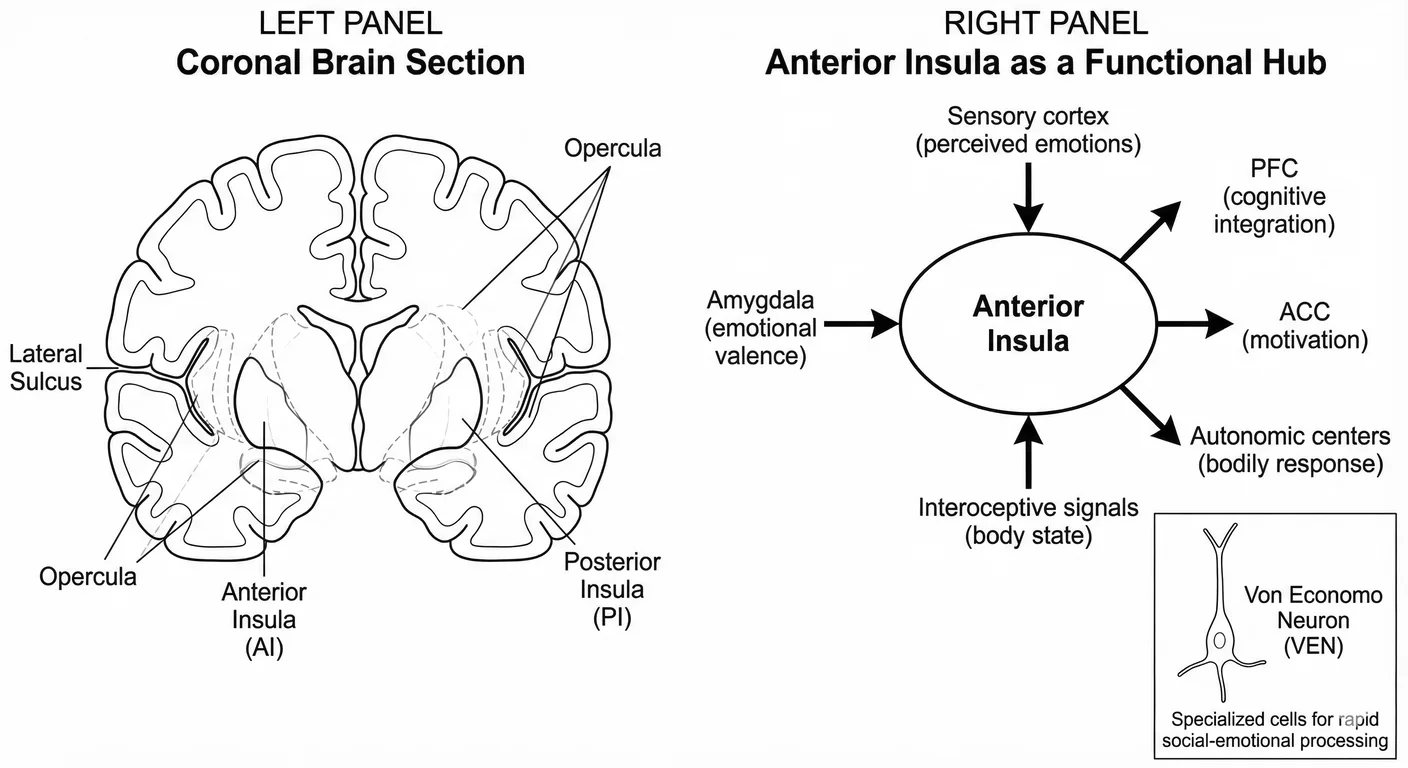

The anterior insula (AI) is the brain’s translator—the structure that converts perceived emotion into felt emotion. When you see someone in pain and wince yourself, that’s the AI at work. When a friend’s grief makes your own chest tighten, that’s translation happening in real time. 1143

The AI integrates what you see on another’s face with simulated bodily responses in your own body. It is densely populated with Von Economo neurons and richly connected to the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate. 852 It is the hub where social perception becomes embodied experience.

In early adversity, the translator morphs. Adults with histories of childhood maltreatment show reduced AI volume—a reduction correlated with maltreatment severity that persists decades later. 1219 710 Their AI connectivity is altered: stronger links to the amygdala (heightening reactivity), weaker links to prefrontal cortex (reducing regulation). 289 Many show alexithymia—difficulty identifying their own emotions—because the AI that should translate bodily states into conscious feelings has developed with impaired function. 420

This is why Laura, holding her crying daughter, can observe Maisie’s distress without feeling it land anywhere inside her. Her translator is present but silent. The structure exists but has morphed to fit an environment where emotional resonance was unavailable. She can see the pain. She cannot feel it. The translation fails.

Knowing Without Feeling: Two Networks, One Broken

The brain has two distinct empathy networks, and early adversity does not damage them equally. 1122

The affective network—anterior insula, anterior cingulate, amygdala—handles feeling what others feel. This is embodied empathy, the kind that makes your chest tighten when a friend describes their loss.

The cognitive network—temporoparietal junction, medial prefrontal cortex—handles understanding what others think and believe. This is mentalising, theory of mind, the cold calculation of another’s mental state.

These networks can be dissociated. Damage the affective network and you lose the feeling but keep the understanding. Damage the cognitive network and you lose the understanding but keep the feeling. 1122

In narcissism, the affective network is impaired while the cognitive network is preserved—sometimes even enhanced. This is not paradox but survival. 832

The child of the narcissistic parent must become an expert mind-reader. They must anticipate the parent’s moods, predict their reactions, read the room before entering it. This hypervigilant attention to others’ mental states strengthens the cognitive empathy circuits. Meanwhile, the parent does not feel with the child—does not mirror, does not resonate—so the affective circuits wither from disuse.

The result is the characteristic narcissistic profile: they can read you perfectly while feeling nothing. They know what you’re thinking. They just don’t care. The cognitive network functions; the affective network has gone silent. They have become expert knowers and failed feelers—exactly what their environment trained them to be.

From Mirroring Failure to Empathy Void

The developmental pattern follows the same logic we have seen in the stress and reward systems: the child adapts to what they receive.

The narcissistic parent does not mirror. They ignore the infant’s expressions, or respond with their own unrelated emotional states, or mirror only selectively—responding to expressions that serve their needs while ignoring others. 1236 263 The infant cannot build accurate mappings between felt and perceived emotion. Their VENs multiply during years when no one feels with them. Their anterior insula develops without the resonant input it needs.

Meanwhile, survival demands hypervigilant attention to the parent’s states. The child becomes an expert mind-reader because they must. The cognitive empathy circuits strengthen through constant use; the affective circuits wither from neglect. 832 By adolescence, pruning consolidates the asymmetry: underused affective circuits are cut while heavily used cognitive circuits are reinforced. 1219

By adulthood, the pattern is fixed. The narcissist can read minds but cannot feel with them. They understand what you’re experiencing—often with uncanny accuracy—but this understanding does not produce the visceral resonance that would motivate compassion. 1037 Research shows they can activate affective empathy when explicitly instructed to do so, when imagining themselves in another’s position, when the other provides supply. 544 The circuitry exists but requires effortful activation rather than automatic resonance. They must choose to feel, which means they must be motivated to feel. Usually, they are not.

The Scales on the Empathy System

The empathy network, like the stress and reward systems, can develop as skin or as scales. In healthy development, resonance is automatic and flexible (skin). In disrupted development, resonance is blocked or selective—the AI activating only for those who matter to the self (scales). 1097

These scales serve their function, protecting against the flooding that would occur if the child had felt the narcissistic parent’s rage or neediness without defence. But they also imprison. The adult narcissist cannot remove them at will. They can perform empathy—they know the choreography by heart—but they cannot feel it. Laura, at the kitchen table, executing the comforting gestures while thinking about her gallery commission, knows exactly what she should feel. The problem is that knowing and feeling are not the same thing. The scales have become the self.

Implications: Understanding the Empathy Void

Why Cognitive Empathy May Enhance Harm

A common misconception is that empathy deficits make narcissists unaware of the harm they cause. The opposite may be true. Preserved cognitive empathy means the narcissist understands they are causing pain. They see the hurt in their victim’s face. They predict the suffering their actions will cause. They simply do not feel it as aversive.

This combination—accurate understanding without affective resonance—is what enables calculated cruelty. The narcissist can predict how to hurt most effectively precisely because they understand others’ vulnerabilities. Their exploitation is not blind; it is informed by accurate mental state reading, unrestrained by the affective empathy that would make such exploitation viscerally unpleasant. 1287

The Paradox of Empathy on Demand

Research shows that narcissists can show affective empathy when instructed to do so. 544 If asked to imagine themselves in another’s situation, if prompted to take the other’s perspective explicitly, if the other is framed as an admirer or ally, their AI may activate appropriately.

This finding has important implications. It suggests the affective empathy circuitry is not destroyed—it is conditionally suppressed. The scales can, under specific conditions, be temporarily lifted. The question for therapy becomes: How can we expand the conditions under which affective empathy activates?

But it also suggests limits. The narcissist’s empathy requires effortful activation rather than automatic resonance. They must choose to empathise, which means they must be motivated to do so. In most situations, they are not. The conditional nature of their empathy means it will be deployed strategically, when beneficial to the self, not consistently, as genuine other-concern requires.

The AI as Therapeutic Target

The AI’s role in affective empathy points to a therapeutic direction. Interventions that enhance interoceptive awareness—mindfulness, body-based therapies, practices that strengthen the felt sense of bodily states—may indirectly strengthen empathic capacity by improving AI function. 374

This is not a quick fix. The morphing of the AI occurred over years; reversing it would require years of sustained therapeutic input. While the postnatal increase in VEN numbers likely reflects developmental processes rather than adult neurogenesis, 23 existing circuits can theoretically be strengthened, new connections formed, and function enhanced—but only with consistent, long-term effort.

Here the prognosis becomes sobering. Research on NPD treatment shows dropout rates of 63–64%, with motivation typically driven by external crises rather than genuine desire for change. 1050 1055 The individual with consolidated NPD will not voluntarily devote years to developing affective empathy for others’ benefit—others’ experiences do not register as mattering enough to warrant such investment. When narcissists do enter therapy, it is typically because external circumstances have become intolerable, not because they seek to reduce the harm they cause. And when the crisis passes, so typically does the motivation. The conditional nature of their empathy extends to the therapeutic relationship itself: they may engage when therapy serves as a source of supply or status, but genuine transformation requires a sustained commitment that the disorder itself precludes.

The Tragedy of the Defended Heart

The empathy circuit is where the tragedy becomes starkest. The hypervigilant stress response and the insatiable reward system cause suffering primarily to the narcissist themselves (though they harm others as well). The impaired empathy circuit causes suffering primarily to others—the partners, children, friends, and colleagues who are seen but not felt.

Yet behind this harm lies an earlier harm. The narcissist’s impaired empathy began as their own experience of not being empathised with. They developed scales because no one felt with them, so they learned not to feel with others. Their defended heart is an adaptation to a world that did not meet their emotional needs.

This does not excuse the harm they cause. Understanding is not justification. But it does reframe our understanding. The narcissist is not simply selfish or evil. They are carrying the neural signature of having their own emotional states systematically ignored. They treat others as they were treated—not through conscious choice, but through neural circuits that morphed to match the relational environment they received.

The affective empathy that would prevent them from causing harm is the same capacity that was never developed because no one showed them what affective empathy felt like. The gap where compassion should be is the shape of their own unmet need.

The infant’s experience of being (or not being) empathically met shapes neural structures from VENs to the anterior insula to the distributed empathy network. The narcissistic empathy deficit—preserved cognition with impaired affect—reflects the selective morphing of these circuits in response to an environment that demanded mind-reading for survival while offering no model or motivation for heart-feeling.

Together with the stress response pathway and the reward-attachment system, the empathy circuit provides a complete neural account of how early relational environment becomes adult personality structure. In each case, the mechanism is the same: diamorphic agency—the morphing of neural systems to fit available input space, consolidated through cellular, synaptic, and epigenetic mechanisms into increasingly rigid configurations. The palace becomes maze, the skin becomes scales, and the child who needed empathy becomes the adult who cannot give it.