The previous chapter traced the survivor’s personal journey from recognition through post-traumatic growth. But as survivors progress through their healing, a painful question frequently emerges: “If I can change this much, why cannot they?” This question deserves a thorough, evidence-based answer—one that validates the survivor’s efforts, avoids providing false hope of the abuser’s transformation, and explains why their love, patience, and sacrifice could never have been enough. Understanding the neurobiological barriers to narcissistic change serves an important function in recovery: it releases survivors from the burden of believing they could have done something differently to “fix” their abuser.

The Narcissist’s Dilemma—Is Transformation Possible?

The intractability of narcissistic personality disorder at the individual level, combined with the systemic enablers explored in Chapters 8–15, illuminates why personal healing alone cannot address the epidemic of narcissistic abuse. If individuals with this pathology rarely seek help and even more rarely change, then waiting for abusers to transform leaves victims perpetually vulnerable. This reality demands that we shift our focus from changing narcissists to changing the systems that enable them. The same structures that make it difficult for individuals to recover—economic dependence, legal frameworks that prioritise abusers’ rights, therapeutic models that misunderstand abuse dynamics—require collective action and systemic reform.

The Therapeutic Challenge

As stated before, the statistics about narcissistic personality disorder treatment are sobering. A major review published in Focus: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry found that 63-64% of NPD patients drop out of therapy, one of the highest rates among all mental health conditions 1055 . This is not simply resistance to change—it is that the very nature of NPD makes therapy feel like an existential threat. To engage genuinely in therapy would require acknowledging that the grandiose false self is indeed false, that the shame it protects against is real, that the damage inflicted on others matters. For someone whose entire psychological architecture is built on avoiding these truths, therapy represents annihilation.

Dr Elinor Greenberg, who has specialised in treating personality disorders for over forty years, describes the challenge: “Imagine you built your house on a cliff edge. Someone comes along and says, ‘Your foundation is crumbling; we need to demolish and rebuild.’ But you know that demolition means falling into the abyss below. That is what therapy feels like to someone with NPD. Their entire identity is built on not looking at what is underneath.”

Most therapists, recognising these challenges, simply refuse to treat NPD. They know the narcissistic client will likely challenge their competence, attempt to control sessions, use psychological knowledge as ammunition against others, potentially file complaints when confronted, and ultimately leave therapy having wasted everyone’s time while potentially causing harm to the therapist’s other clients through waiting room encounters or review bombing. The few therapists who do specialise in NPD often charge premium rates, do not accept insurance, and maintain strict boundaries that narcissists experience as intolerable injury.

The Neuroscience of Intractability

Brain imaging studies confirm measurable differences in narcissistic brains that help explain why change is so difficult. In earlier chapters we covered how research by Schulze and colleagues found reduced grey matter in areas associated with empathy, particularly the left anterior insula and rostral anterior cingulate cortex 1104 . The narcissist’s inability to feel genuine empathy is not just psychological—it is neurological. That surprises most laypeople as they naturally believe they are interacting with a real person, and not a false self projected neurally as a mask over basic animal needs. While neuroplasticity means brains can change, the willingness to endure the discomfort required for that change is precisely what narcissism prevents.

Consider what neuroplastic change requires: consistent practice of new behaviours that initially feel wrong, uncomfortable, even threatening. The narcissist would need to practice empathy despite feeling nothing, acknowledge harm despite believing they are always right, tolerate shame despite their entire personality being organised around avoiding it. Each therapeutic exercise would trigger the very wounds narcissism exists to protect against.

Dr Craig Malkin, author of Rethinking Narcissism, 788 puts it bluntly: “Asking a narcissist to develop empathy is like asking someone with paralysed legs to walk. The difference is, the paralysed person knows they cannot walk and might welcome treatment. The narcissist is convinced they are an Olympic runner and everyone else is just jealous of their speed.”

When Change Appears to Occur

Sometimes narcissists do appear to change, leading their victims to hope that transformation is possible. These apparent changes typically fall into several categories, none of which represent genuine growth:

The Hoover Maneuver: Named after the vacuum cleaner, hoovering describes the narcissist’s attempt to “suck” their victim back into relationship. The narcissist may attend therapy, read self-help books, apologise profusely, even cry genuine tears. But this performance lasts exactly as long as it takes to regain control. Once the victim returns, the mask drops, leaving them often worse off than before.

Strategic Adaptation: Some narcissists, particularly those with high intelligence and self-awareness, learn to mimic empathy well enough to maintain relationships and avoid consequences. They study emotional responses like an actor preparing for a role, delivering perfectly calibrated performances of care. But this is not growth—it is enhanced manipulation, using therapeutic language and emotional intelligence concepts as more sophisticated tools of control.

Age-Related Mellowing: Some research suggests narcissistic traits may decrease with age, particularly after 40. But this often reflects decreased energy for maintaining the grandiose facade rather than genuine development of empathy. The aging narcissist may simply lack the stamina for constant manipulation, settling into a quieter but fundamentally self-centred existence.

Crisis-Induced Compliance: When faced with genuine consequences—job loss, divorce, legal troubles—narcissists may temporarily comply with treatment demands. They’ll attend therapy, take medication, follow behavioural contracts. But this is survival strategy, not transformation. The moment they regain stability, old patterns reassert themselves.

The Harm Reduction Approach

Given the poor prognosis for genuine transformation, some clinicians advocate for harm reduction rather than cure. Like treating addiction where abstinence is not achievable, the goal becomes minimising damage rather than eliminating pathology. A narcissist might learn to:

-

Recognise when they are about to rage and remove themselves

-

Follow behavioural contracts about specific actions (not calling at work, attending children’s events)

-

Limit their validation seeking to domains where it causes less harm (professional rather than family)

-

Practice “good enough” parenting behaviours even without feeling genuine care

-

Maintain relationships through behavioural rules rather than emotional connection

This approach can reduce harm to others, but it requires the narcissist to acknowledge they have a problem and commit to ongoing management—exactly what most narcissists refuse to do. It also places the burden on victims to accept a relationship with someone incapable of genuine care, trading acute abuse for chronic emotional deprivation.

Therapeutic Modalities for Survivors

While narcissists rarely change, survivors absolutely can—and do. Trauma treatment has transformed radically in the past two decades, moving from purely cognitive approaches to integrated modalities that address trauma’s full impact—neurobiological and somatic. For narcissistic abuse survivors, this evolution offers hope where traditional therapy often failed. The following approaches represent the current state of the art, though the field continues to evolve as our understanding of trauma deepens.

The Foundation: Trauma-Informed Care

The principles of trauma-informed care undergird all effective therapeutic approaches. Developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), trauma-informed care recognises that trauma is widespread, that people have multiple pathways to recovery, that trauma affects entire families and communities, and that services must actively resist retraumatisation 1079 .

For narcissistic abuse survivors, trauma-informed care means:

Safety First: Physical and emotional safety must be established before processing trauma. A therapist pushing a client to “work through” trauma while they are still in danger or barely stable retraumatises rather than heals.

Trustworthiness and Transparency: After being gaslit, survivors need relationships where reality is consistent and clearly communicated. Therapists must be reliable and willing to acknowledge their own limitations.

Collaboration: Rather than therapist as expert and client as patient, trauma-informed care recognises survivors as experts on their own experience. The therapist brings clinical knowledge; the client brings lived expertise.

Empowerment and Choice: Having been controlled and coerced, survivors need to reclaim agency through choices about treatment approaches and goals, including the right to say no and to change course.

Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues: Trauma intersects with identity in complex ways. A woman’s experience of narcissistic abuse is shaped by cultural messages about female submission. A Black survivor faces additional challenges when seeking help from systems that have historically failed their community. LGBTQ+ survivors may have been targeted specifically around their identity. Trauma-informed care acknowledges these intersections.

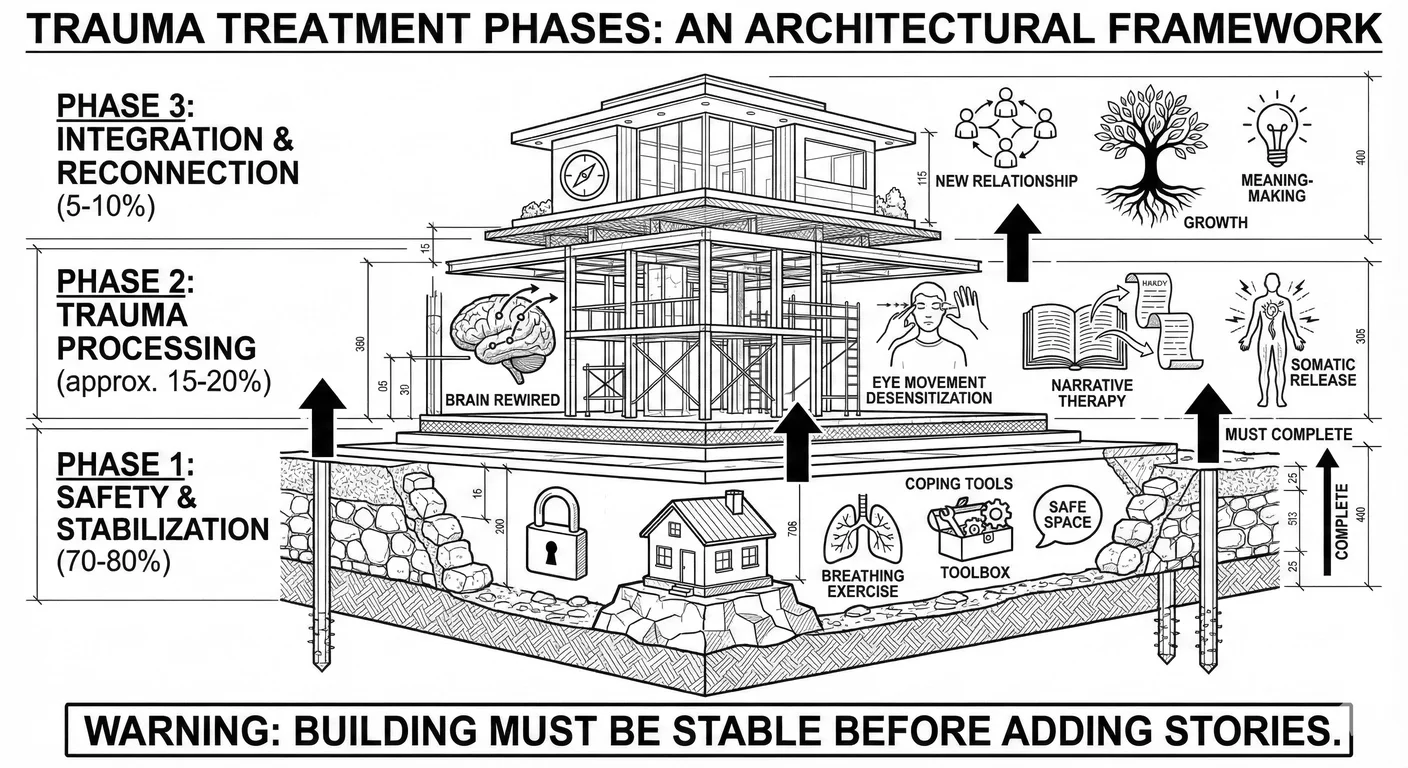

Phase-Based Treatment: The Universal Framework

Regardless of specific modality, effective trauma treatment follows a phase-based approach first articulated by Pierre Janet in the 19th century and refined by Judith Herman and others. The three phases—safety and stabilisation, trauma processing, and integration—provide a roadmap that prevents the overwhelm and retraumatisation that can occur when trauma is approached too directly too quickly.

Phase 1: Safety and Stabilisation typically comprises 70–80% of treatment time for complex trauma. The survivor learns to:

-

Recognise and manage triggers

-

Develop self-soothing techniques

-

Establish basic daily routines

-

Build support networks

-

Practice boundary setting

-

Stabilise any co-occurring conditions (addiction, eating disorders, self-harm)

Phase 2: Trauma Processing only begins when the survivor has sufficient internal and external resources. Processing might involve:

-

EMDR for specific traumatic memories

-

Narrative therapy to create coherent life story

-

Somatic experiencing to discharge trapped trauma

-

Expressive therapies (art, music, movement) to access non-verbal trauma

-

Group therapy for shared witnessing and validation

Phase 3: Integration and Reconnection involves taking the insights and healing from therapy into daily life:

-

Developing secure relationships

-

Finding meaning and purpose

-

Contributing to others’ healing

-

Creating new life narrative that includes but is not defined by trauma

-

Ongoing maintenance of mental health

Somatic Approaches: Healing Through the Body

The recognition that trauma is stored in the body has transformed treatment. Traditional talk therapy, while valuable for creating narrative coherence and cognitive understanding, often fails to address the physiological dysregulation that underlies many trauma symptoms. Somatic approaches work directly with the body’s wisdom, bypassing the cognitive defences that can keep healing at arm’s length.

Polyvagal Theory and Clinical Applications

Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal Theory Polyvagal Theory A neurobiological theory developed by Stephen Porges explaining how the autonomic nervous system regulates social engagement, fight-or-flight, and shutdown responses. Essential for understanding trauma responses and why abuse survivors may freeze, dissociate, or struggle with connection. has offered a neurobiological framework for understanding trauma responses and recovery. The theory identifies three evolutionary stages of our autonomic nervous system: the ventral vagal state of safety and social engagement, the sympathetic fight-or-flight response, and the dorsal vagal freeze or collapse. Trauma disrupts our ability to accurately detect safety and danger—what Porges calls “neuroception”—leaving survivors either hypervigilant or dissociated 1001 .

For narcissistic abuse survivors, polyvagal-informed therapy focuses on:

-

Recognising their current nervous system state

-

Learning to shift states consciously through breath and movement

-

Developing accurate neuroception—distinguishing real from perceived threat

-

Building ventral vagal tone through safe social connection

-

Understanding their responses as adaptive rather than pathological

Deb Dana, a clinical social worker who has translated polyvagal theory into practical therapeutic applications, offers simple exercises. The “ventral vagal brake” exercise involves extending exhales longer than inhales, activating the parasympathetic nervous system. The “social engagement system” exercise uses humming, singing, or gargling to stimulate the vagus nerve. These might seem simplistic, but for survivors whose nervous systems have been dysregulated for years, they offer concrete tools for state management 287 .

Somatic Experiencing

Somatic Experiencing Somatic Experiencing A body-based trauma therapy that works with physical sensations to release trapped survival energy and restore nervous system regulation. , developed by Dr Peter Levine, works with the body’s natural healing mechanisms. Rather than retelling trauma stories, which can retraumatise, the approach focuses on sensation—the tightness in the chest, the knot in the stomach, the tension between the shoulder blades. By gently attending to these sensations, allowing them to move and discharge, the trapped energy of trauma can release. Research indicates significant reduction in PTSD symptoms through somatic approaches, with some studies reporting up to 90% improvement 160 .

For survivors of narcissistic abuse, somatic work addresses specific body patterns. The chronic hypervigilance that scans for the narcissist’s mood shifts has generated a nervous system stuck in high alert. The suppression of authentic expression has created muscular armouring—tension patterns that literally hold back words never spoken, tears never shed, screams never released. The disconnect from their own needs has created dissociation from body signals—hunger, exhaustion, pain, pleasure all muted or absent.

Tom, a survivor of narcissistic abuse, describes his somatic therapy: “For twenty years with my narcissistic father, then ten more with a narcissistic boss, I lived in my head. My body was just something that carried my brain around. In somatic therapy, I learned I had been holding my breath for thirty years. When I finally let it out—really let it out—I sobbed for an hour. It was not sad crying but relief, like my body was finally allowed to exist.”

EMDR: The Gold Standard for Trauma Processing

EMDR EMDR Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing—a trauma therapy that uses bilateral stimulation to help process and integrate traumatic memories. (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) has emerged as one of the most effective treatments for trauma, with particular relevance for narcissistic abuse survivors. The therapy uses bilateral stimulation—usually eye movements but sometimes taps or tones—to help the brain reprocess traumatic memories. Unlike traditional therapy that requires detailed verbal processing of trauma, EMDR allows healing with minimal retelling—valuable for survivors who have been gaslit into doubting their own narratives.

EMDR’s effectiveness for PTSD is now so well-established that it is recommended as a first-line treatment by organisations including the World Health Organisation, the American Psychiatric Association, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Studies demonstrate that 84-90% of single-trauma victims no longer meet PTSD criteria after just three 90-minute sessions. For multiple-trauma victims, including those with Complex PTSD from prolonged narcissistic abuse, 77% achieve remission after six sessions 800 . Combat veterans, a population notorious for treatment-resistant PTSD, show 77% remission rates after twelve sessions 200 .

For narcissistic abuse survivors, EMDR offers particular advantages:

No detailed retelling required: For survivors who have been gaslit into doubting their own narratives, who struggle to find words for experiences that were systematically denied, this matters greatly. They do not need to convince anyone, including themselves, that the trauma was “bad enough.”

Addresses negative core beliefs: Through the process, beliefs like “I’m worthless,” “I cannot trust myself,” “I deserve bad treatment” are systematically challenged and replaced with adaptive alternatives. This is not positive thinking or affirmation but neurological rewiring.

Works relatively quickly: While complex trauma requires more sessions than single-incident trauma, many survivors experience significant relief within 12-20 sessions.

A 2021 study in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology found that EMDR therapy has a symptom-reducing effect not only on memories of traumatic events meeting the PTSD A-criterion but also on memories involving other types of adverse events, including emotional abuse and neglect. 618 One participant describes the experience: “I went in with this specific memory—him screaming at me while I cowered in the bathroom. Through the eye movements, other connected memories came up, my mother doing the same thing, a teacher who humiliated me, this whole chain of experiences where I learned I was worthless. By the end of the session, that bathroom memory had lost its power. I could remember it without feeling like I was back there. For the first time in years, it was actually in the past.”

Internal Family Systems: Harmonizing the Internal World

internal family systems (IFS), developed by Dr Richard Schwartz, has gained tremendous momentum in recent years, particularly for complex trauma where the psyche has fragmented into multiple protective parts. IFS posits that the psyche contains multiple “parts”—sub-personalities that developed to handle different situations. In narcissistic abuse, these parts often include harsh inner critics that echo the narcissist’s voice, hypervigilant protectors scanning for danger, exiled children holding pain from different developmental stages, and firefighter parts that numb overwhelming feelings through various strategies.

Research on IFS shows strong effectiveness, with 92% of participants reporting significant improvement in trauma symptoms 1108 . For narcissistic abuse survivors, IFS explains the internal confusion they experience—why part of them still loves the abuser while another part knows the truth, why they can be strong in some situations but collapse in others, why healing feels like internal warfare.

The process begins with identifying parts. The survivor might recognise:

-

A hypervigilant protector constantly scanning for danger

-

An inner critic that preemptively attacks to avoid external criticism

-

A people-pleasing part that tries to earn love through perfection

-

An angry rebel that wants to destroy everything connected to the abuser

-

Young exiled parts holding pain from different developmental stages

-

A numb dissociator that checks out when things get overwhelming

Rather than trying to eliminate these parts, IFS helps the survivor understand each part’s protective intention. The harsh inner critic, that voice that sounds exactly like the narcissist, is recognised as a protector that learned to anticipate and internalise criticism to avoid worse external abuse. The part that still loves the narcissist is honoured as holding the capacity for attachment, even if it attached to someone harmful. The hypervigilant part is thanked for its service in keeping the person alive through genuine danger.

The IFS clinical literature contains numerous accounts of survivors meeting exiled parts. One case study describes a client’s experience: “There was this eight-year-old part of me that had been frozen in time, holding all the terror from when my mother would rage. When I finally accessed him in therapy, he was still cowering in a closet, had been for forty years. I told him I was here now, that I’m an adult who can protect him. The relief in my body was indescribable. That chronic tension I’d carried my whole life, it was that little boy, still braced for impact.” Dr Schwartz describes this as “unburdening”, the exiled part, finally witnessed and protected by the client’s Self, can release the pain it has been carrying, often for decades. 1108

Choosing an Approach

The therapeutic modalities most effective for narcissistic abuse recovery share a common understanding: healing must address the nervous system, not just thoughts and feelings. Each approach offers distinct pathways to integration, and survivors often find that combining modalities—somatic work to discharge trapped energy, EMDR to reprocess traumatic memories, IFS to harmonize internal conflicts—creates synergistic healing. The choice of approach matters less than finding what resonates with the individual survivor’s needs and readiness.

Relational Reconstruction

Narcissistic abuse fundamentally damages our capacity for relationship—with others, with ourselves, with the world. Recovery requires healing from past harm while actively rebuilding relational capacities that may never have fully developed. This reconstruction happens in concentric circles, starting with the self, expanding to intimate relationships, then family systems, and ultimately community.

The Self-Relationship: Foundation for All Others

Before survivors can build healthy relationships with others, they must establish a caring, trustworthy relationship with themselves. This sounds simple but embodies a real challenge for those whose self-relationship was colonised by a narcissistic abuser. The internalised narcissistic voice—critical, contemptuous, dismissive—must be recognised as an interloper and gradually replaced with self-compassion.

Dr Kristin Neff’s research on self-compassion identifies three components: self-kindness rather than self-judgement, common humanity rather than isolation, and mindfulness rather than over-identification with thoughts and feelings. For narcissistic abuse survivors, each component requires deliberate cultivation:

Self-Kindness: After years of self-blame reinforced by the narcissist, survivors often treat themselves more harshly than they would ever treat others. Learning self-kindness might begin with imagining what they would say to a friend in their situation, then gradually directing that same compassion inward.

Common Humanity: Narcissistic abuse isolates victims, making them feel uniquely flawed or cursed. Recognising that millions of others have survived similar abuse, that their responses are normal reactions to abnormal treatment, breaks this isolation.

Mindfulness: Rather than being consumed by self-critical thoughts or drowning in emotions, mindfulness creates space to observe inner experience without being controlled by it. “I’m having the thought that I’m worthless” creates distance from “I am worthless.”

Dating After Narcissistic Abuse

The prospect of romantic relationship after escaping a narcissist can be simultaneously terrifying and compelling. The survivor craves the genuine connection they were denied, yet fears repeating patterns that led to abuse. They have developed hypervigilance for red flags but may struggle to recognise or trust green ones. The intensity and drama of the narcissistic relationship has conditioned their nervous system to equate chaos with love, making healthy relationships feel boring or suspect.

Why Healthy Feels Wrong

Survivors consistently report that healthy relationships initially feel uncomfortable, even wrong. Where is the instant intensity, the soul mate declarations, the feeling of being consumed by passion? The narcissist’s love bombing—that initial phase of overwhelming attention, premature intimacy, and grandiose promises—hijacked normal attachment systems, creating addiction-like bonding. Now, appropriate pacing feels like disinterest. Respect for boundaries feels like lack of desire. Consistency feels like boredom.

Understanding the neuroscience helps normalise these feelings. The narcissistic relationship generated a trauma bond reinforced by intermittent reinforcement—the most addictive psychological pattern known. The brain became conditioned to seek the dopamine hit of reconciliation after conflict, the relief of affection after cruelty. A stable, drama-free relationship provides steady serotonin and oxytocin but lacks the dopamine spikes the survivor’s brain has learned to crave. Like any addiction recovery, there is a period of withdrawal where the brain slowly recalibrates to find satisfaction in stability.

The work involves tolerating this discomfort while the nervous system adjusts. Survivors might need to consciously remind themselves: “This feels boring because it is safe. This feels wrong because I was conditioned to chaos. This person’s consistency is not lack of passion—it is emotional maturity.” Over time, usually 12-24 months, the nervous system adapts, and stability begins to feel satisfying rather than suffocating.

Green Flags That Feel Like Red Flags

After narcissistic abuse, positive relationship qualities can trigger anxiety because they are so foreign. The survivor must learn to recognise and tolerate green flags:

They respect your no: After years with someone who bulldozed boundaries, a partner who accepts “no” without argument, guilt-trips, or punishment feels suspicious. The survivor thinks, “They must not really want me.” In reality, respect for boundaries indicates healthy attachment—they want you to want them, not to comply from obligation or fear.

They are consistent: The narcissist’s unpredictability kept the survivor constantly off-balance. A partner whose mood is stable, whose affection is reliable, whose words match actions, feels unsettling. Where is the mystery, the challenge, the excitement? But consistency allows trust to build—the foundation for genuine intimacy rather than trauma bonding.

They have their own life: The narcissist’s possessiveness felt like love—they wanted to know everything, be involved in everything, control everything. A partner with healthy independence, who encourages the survivor’s autonomy, might initially feel uninvested. But interdependence, not codependence, characterises healthy relationship.

They admit mistakes: The narcissist never genuinely apologised, never took accountability, never acknowledged harm. A partner who says, “I was wrong, I’m sorry, how can I make this right?” might trigger disbelief or even fear—waiting for the manipulation that must surely follow. Learning to receive genuine accountability requires recognising it as strength, not weakness.

They are interested in your inner world: The narcissist only cared about the survivor’s thoughts and feelings as they related to the narcissist. A partner genuinely curious about the survivor’s inner experience, who remembers details, who asks follow-up questions, who celebrates their growth, might feel invasive or performative. The survivor must learn to distinguish genuine interest from intelligence gathering.

Family Reconstruction: Breaking and Remaking Bonds

For survivors from narcissistic families, recovery involves individual healing combined with handling complex family dynamics. Some relationships might be salvageable with new boundaries. Others might require permanent severance. Still others exist in liminal space—minimal contact, surface interaction, careful management.

When No Contact Becomes Necessary

No contact is vital protection—distinct from vengeance—when every interaction retraumatises, when the narcissist refuses to acknowledge harm, when abuse continues. The decision typically comes after years of failed attempts: boundaries ignored, therapy weaponised, limited contact escalated. No contact acknowledges that the relationship cannot be salvaged and that self-protection takes precedence.

For detailed guidance on implementing no contact, managing flying monkeys, and the extinction burst that follows, see Chapter 19.

Parenting After Narcissistic Abuse

For survivors with children, parenting presents unique challenges. If co-parenting with a narcissist, they must navigate ongoing abuse while protecting children. If parenting alone, they must heal their own wounds while meeting children’s needs. Either way, they face the terror of repeating patterns—becoming the narcissist they fled or swinging to opposite extreme of boundaryless permissiveness.

Parallel Parenting

Traditional co-parenting fails with narcissists. Parallel parenting—operating independently within custodial time, written communication only, divided decisions—protects children from ongoing conflict. For detailed implementation, see Chapter .

Systemic and Cultural Interventions

Individual healing, while essential, cannot be separated from the systems that enable narcissistic abuse. True recovery requires personal transformation joined with collective action to change the structures that trap victims with abusers, reward narcissistic behaviour, and punish those who resist. This is where the personal becomes political, where individual healing becomes social revolution.

Economic Justice as Abuse Prevention

The statistics are undeniable: financial abuse occurs in 99% of domestic violence cases 918 . This is strategy, never coincidence. Abusers understand that economic dependence is the most effective chain, that victims who cannot afford to leave will not leave, no matter how severe the abuse. Our economic system, with its vast inequality, expensive housing, inadequate childcare, and employment insecurity, creates perfect conditions for abusers to trap their victims.

Consider the practical barriers to leaving: First month’s rent, last month’s rent, and security deposit on new housing can easily total $3,000-5,000. Legal fees for divorce and custody proceedings average $15,000-30,000. Childcare costs while working can exceed $1,000 per month per child. Healthcare, if lost through leaving a spouse’s insurance, can cost hundreds per month. Transportation, if the abuser controls the vehicle, requires thousands for even a basic used car. The survivor needs not just enough money to leave but enough to sustain independent life while potentially battling a vengeful narcissist with greater resources.

Universal basic services would fundamentally alter this equation. Guaranteed housing would mean victims are not choosing between abuse and homelessness. Universal healthcare would eliminate insurance dependence on abusive spouses. Universal childcare would enable economic independence through work. These are not radical ideas—many developed nations provide these services—but in the United States, their absence generates a trap that narcissists exploit.

Legal System Reform

The family court system, designed with the assumption that children benefit from relationships with both parents, transforms into a weapon in the hands of narcissistic abusers. The concept of “parental alienation”—the idea that one parent is turning children against the other—has been particularly devastating. Despite lacking scientific validity and being rejected by the American Psychological Association, parental alienation accusations are used to discredit protective parents and force children into relationships with their abusers.

Dr Joan Meier’s research revealed the scope of this problem: when mothers alleged abuse and fathers claimed alienation, courts were 2.3 times more likely to disbelieve the abuse allegations. When alienation was credited, mothers lost custody 44% of the time. Even when abuse was proven, if alienation was also credited, mothers lost custody 28% of the time 845 . The narcissistic abuser has learned that crying “alienation” is often more effective than denying abuse.

Reform requires fundamental changes:

-

Training judges in personality disorders and coercive control dynamics

-

Rejecting parental alienation as a valid concept in custody decisions

-

Recognising psychological abuse as equally harmful as physical abuse

-

Appointing guardians ad litem trained in narcissistic abuse

-

Creating specialised family courts for high-conflict cases involving abuse

-

Implementing supervised visitation when personality disorders are present

-

Enforcing consequences for litigation abuse and false allegations

Therapeutic System Transformation

The mental health system’s failure to adequately address narcissistic abuse is not just about individual therapist competence but systemic issues in training and treatment models. Most graduate programs in psychology and social work provide minimal training on personality disorders and even less on narcissistic abuse specifically. Therapists enter the field equipped to treat depression and anxiety but unprepared for the complex dynamics of coercive control.

Insurance companies compound the problem by limiting coverage to diagnostic codes that do not capture narcissistic abuse’s reality. A survivor might receive a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or PTSD—all accurate but incomplete—while the underlying cause remains unaddressed. Treatment is authorized for symptom management rather than trauma resolution, for individual therapy rather than the intensive, specialised intervention narcissistic abuse recovery requires.

Cultural Narrative Change

Perhaps the deepest change needed is in our cultural narratives about relationships and forgiveness. The myths that keep victims trapped—that love conquers all, that family bonds are sacred regardless of harm, that forgiveness is required for healing—are woven into our literature and daily discourse. Challenging these narratives is essential for creating a culture where narcissistic abuse is recognised, victims are believed, and leaving is supported.

These systemic interventions—economic justice, legal reform, therapeutic training overhaul—may seem overwhelming in scope. Yet history shows us that every social transformation began with individuals who refused to accept the status quo. The survivor reading this chapter, working to heal their own wounds, participates in this larger transformation. Each person who breaks free and shares their story, each professional who learns to recognise narcissistic abuse, each friend who believes and supports a survivor—all contribute to weakening the structures that enable abuse. This brings us to the fundamental truths that can sustain survivors through their journey and beyond.

Conclusion: Creating a Post-Narcissistic World

At the end of this journey through recovery and reconstruction, the larger picture comes into view. Narcissistic abuse is a societal symptom—the inevitable result of systems that reward grandiosity and punish vulnerability. Healing from narcissistic abuse, then, becomes personal recovery and cultural resistance alike.

The Collective Awakening

Something is shifting in our collective consciousness. The explosion of interest in narcissistic abuse—from academic research to social media discussions to popular media representations—suggests we are in a moment of cultural awakening. Google searches for “narcissistic abuse” have increased 500% in the past five years. The hashtag #NarcissisticAbuse has billions of views on TikTok. Support groups that did not exist a decade ago now serve millions worldwide.

This awakening encompasses individual recognition and collective pattern identification. We are beginning to see how narcissistic leadership in politics threatens democracy (Chapter 15), how narcissistic corporate culture destroys both workers and economies (Chapter 14), how narcissistic patterns manifest throughout history (Chapter 1), and how narcissistic family systems perpetuate intergenerational trauma (Chapter 4). The personal is revealing itself as political, the individual as systemic, the psychological as cultural.

The Three Truths

Three truths to hold simultaneously, each essential for the journey ahead:

Truth 1: You Will Heal

The research is clear and hopeful. Post-traumatic growth occurs in 50-70% of trauma survivors 1213 . The brain’s neuroplasticity means that trauma’s neurological impacts can be reversed. Earned Secure Attachment Earned Secure Attachment A secure attachment style developed through healing work and healthy relationships in adulthood, rather than being formed in childhood. It demonstrates that insecure attachment patterns can be changed. is achievable. The survivors who have walked this path before you light the way forward. Healing is possible—probable, even—for those who seek it. You have already survived the worst. Recovery, while challenging, is gentler than what you have already endured.

Truth 2: They Will not Change

The narcissist in your life—whether parent, partner, boss, or friend—will almost certainly not change. With a 63-64% therapy dropout rate and no proven cure, waiting for their transformation is waiting for something that will never come. This is liberation. Stop waiting. Stop hoping. Stop making your healing contingent on their evolution. They are who they are. You can only change your relationship to them, not them themselves.

Truth 3: The System Must Change

Your individual healing is necessary but insufficient. The systems that enabled your abuse—economic inequality, inadequate legal protection, therapeutic ignorance, cultural myths—will continue creating new victims unless we collectively transform them. Your healing is resistance. Your boundary-setting is revolution. Your story-telling is cultural change. Every survivor who breaks free weakens the structures that enable narcissistic abuse.

The Return to Love

Narcissistic abuse is the antithesis of love. Where love sees and celebrates the other’s authentic self, narcissism sees only its own reflection. Where love gives freely, narcissism takes endlessly. Where love connects, narcissism isolates. Where love heals, narcissism wounds.

Recovery from narcissistic abuse is, therefore, about returning to love—genuine care that sees and nurtures. This begins with self-love, extends to chosen family and friends, and ultimately encompasses community and even, for some, the narcissist themselves—through distant compassion—without reconciliation—that we might feel for anyone trapped in the prison of their own pathology.

This return to love is not soft or sentimental. It is fierce, boundaried, discerning love that says no to harm and yes to health. It is love that chooses truth over comfort, growth over stagnation, authenticity over performance. It is love that recognises that sometimes the most loving thing is to leave, that distance can be compassion, that protecting yourself is not selfish but sacred.

The Spell Can Be Broken

Like Narcissus gazing into the pool in Chapter 1, the narcissist remains trapped by their own reflection, unable to see beyond it to authentic existence. But unlike that mythic figure doomed by the gods, you are not condemned to waste away by the water’s edge. The title of this chapter promises that the spell can be broken, and it can. The spell that makes you doubt your reality—broken by validation and evidence. The spell that keeps you bonded to someone who harms you—broken by understanding trauma bonds as neurobiology, not character flaw. The spell that says you are worthless—broken by discovering your inherent value. The spell that isolates you—broken by finding community with fellow survivors. The spell that says this is all there is—broken by glimpsing what lies beyond abuse.

Breaking the spell is daily practice, not a single moment of liberation. It is conscious choice, repeated resistance to old patterns. It is choosing reality over gaslighting, even when reality is painful. It is maintaining boundaries despite guilt and pressure. It is believing yourself worthy of respect and genuine care, even when—especially when—everything in your history suggests otherwise.

The spell can be broken. It breaks through the slow work of rebuilding and healing. It breaks through individual healing and collective action. It breaks through countless small acts of courage—the therapy session attended despite fear, the boundary held despite guilt, the truth told despite consequences, the help sought despite shame.

You are already breaking it. By reading this chapter, by recognising your experience in these pages, by considering that healing is possible, you have begun. The spell’s power lies in its invisibility, in victims not knowing they are under its influence. Once seen, once named, once understood, its power begins to fade. Not all at once—the narcissist’s voice in your head will not suddenly silence, the trauma bonds will not immediately dissolve, the wounds will not instantly heal. But the spell’s hold loosens. Light enters through the cracks. And in that light, recovery becomes not just possible but inevitable.

The journey ahead is long. There will be setbacks and moments when the old patterns reassert themselves with surprising force. But you are not walking alone. Millions of survivors walk with you, some ahead lighting the path, others beside you offering support. Together, we are breaking the spell—for ourselves and our communities. Together, we are creating a world where narcissistic abuse is recognised and healed. Together, we are returning to love.

The spell can be broken. You are already breaking it.

Keep going.