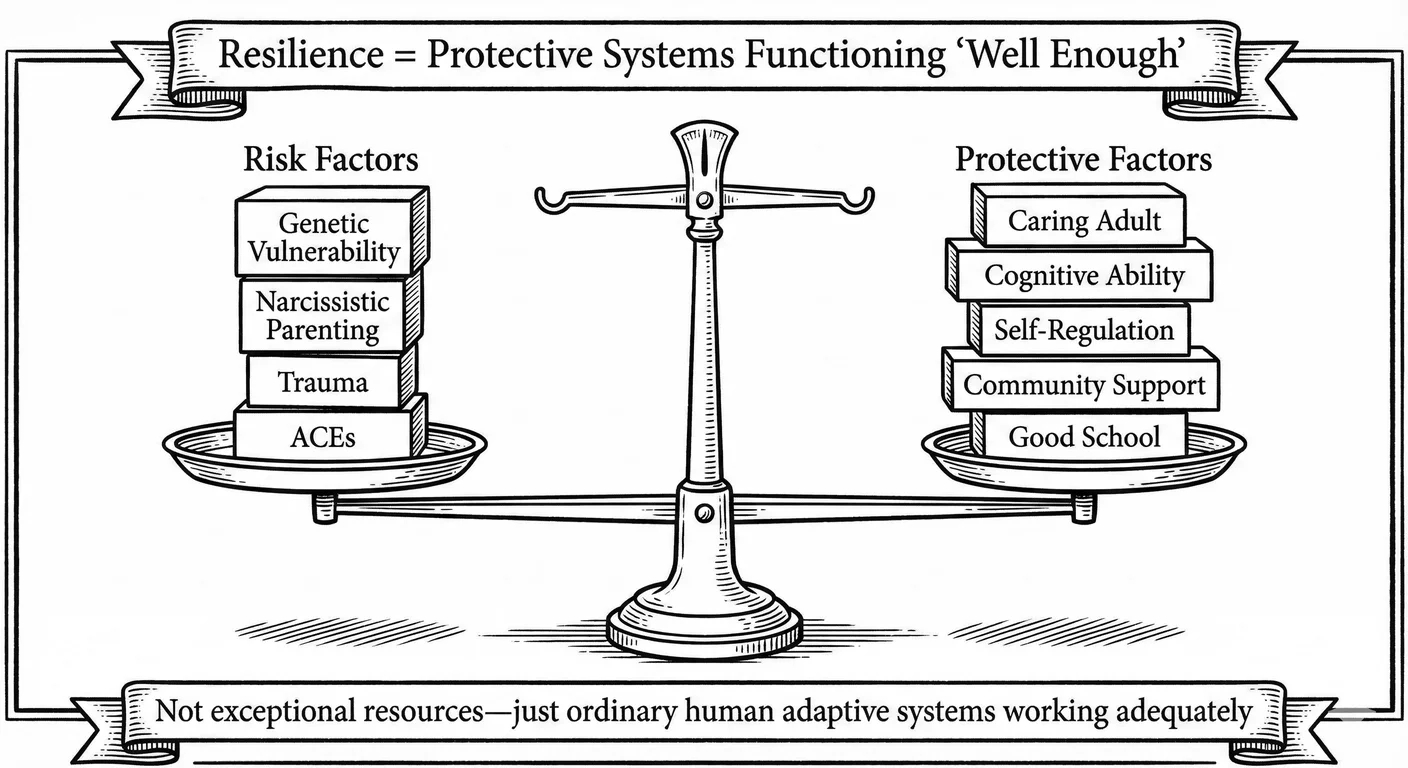

Clinical reality contradicts pessimism—at least when we consider how many children raised by narcissistic parents do not become narcissistic. In fact, many who experience severe developmental trauma achieve notably healthy adult lives. This is great news for them; less so for those building careers on their misery. If narcissism is the convergence of risk factors overwhelming our protective systems, then strengthening those systems (through policy, clinical intervention, or social support) offers hope in prevention and remediation.

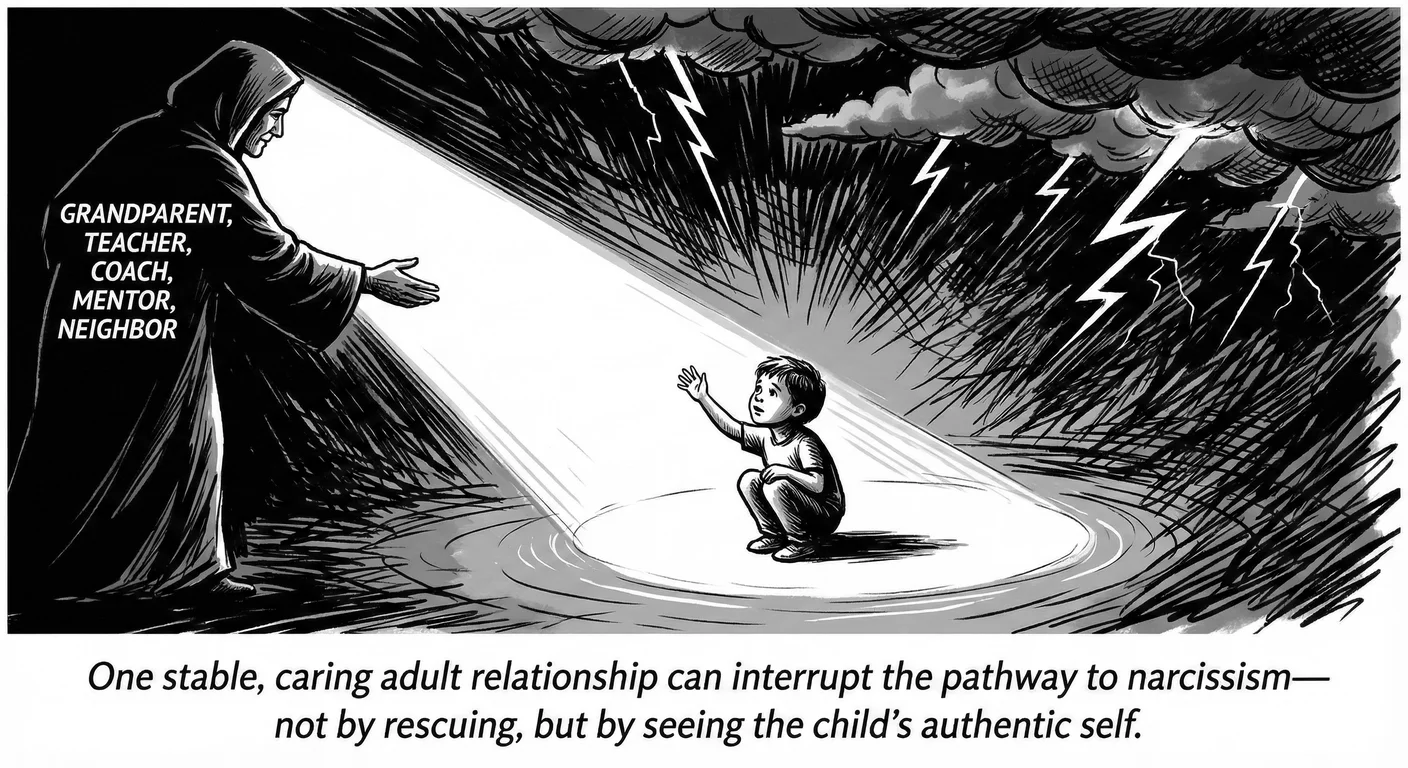

What saved Michael? Not exceptional genes. Not wealth. Not therapy. One person who saw him.

‘Ordinary Magic’: Resilience as Process, Not Trait

A child inheriting high negative affectivity and low effortful control who then gets assigned the role of golden child or scapegoat by a narcissistic parent would appear developmentally doomed. Yet, clinical reality contradicts this fatalism with joyful stubborn persistence. Many—actually, most—children exposed to narcissistic parenting do not become narcissistic 1313 . Many children carrying genetic vulnerabilities never manifest personality pathology. The hushed tones and sucked teeth in clinical offices as expert eyes are cast over test reports are misplaced.

The research is there: if one-third of high-risk children exposed to severe adversity develop into competent, caring adults despite their developmental histories 1313 , then vulnerability and adversity—however necessary—aren’t enough to produce narcissists. Something protects. Something wonderful interrupts the pathway from diathesis and stress to disorder.

From Invulnerability to Resilient Courage

The scientific study of resilience began with a mystery that annoyed developmental psychopathologists in the 1970s, back when behaviourism was the trend in research. 443 They studied children of schizophrenic parents (a population at dramatically elevated risk for psychopathology) and noticed that many children in these high-risk families developed with striking competence. They showed no evidence of the psychiatric disorders or social impairments predicted by their genetic and environmental setup according to the researchers’ best models.

At the same time Rutter 1070 in 1987, talking with children in institutional care, who were experiencing severe deprivation, and Werner 1313 in 1989, following 698 children born into poverty on the island of Kauai, documented the same finding: substantial minorities of high-risk children not only avoided pathology but thrived. They achieved educational success, stable relationships, and psychological wellbeing. This so baffled the researchers that these children were initially characterised as ‘invulnerable’ or ‘stress-resistant.’ The terms implied quasi-magical immunity to adversity, as though they possessed special plot armour protecting them from risks that devastated their peers.

This invulnerability framing highlighting their exceptionality wasn’t just there to protect prevailing theories (and associated funding) from inconvenient scientific results; it fundamentally mischaracterised what was happening. These resilient children were not invulnerable—they experienced distress and often carried psychological scars from their adverse experiences. Their suffering was not reduced, nor their courage diminished.

Yet the researchers said their adaptive functioning was not natural: how could it be? It was a response to threat, requiring active coping, developmental work, and often relational supports. The mythology of invulnerability also implied that resilience resided within the child as a stable trait, either one possessed it or one did not, an essentialist formulation offering little guidance for intervention. It let researchers and the psychiatric industry “off the hook”. If resilience required exceptional, innate qualities, then nothing could be done for children lacking those particular gifts.

In 2001, Masten 813 , synthesising four decades of resilience research in her article “Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in Development,” demolished this mythology with an elegant inversion. The most surprising conclusion from studies of resilient children, Masten argued, ‘is the ordinariness of the phenomena.’

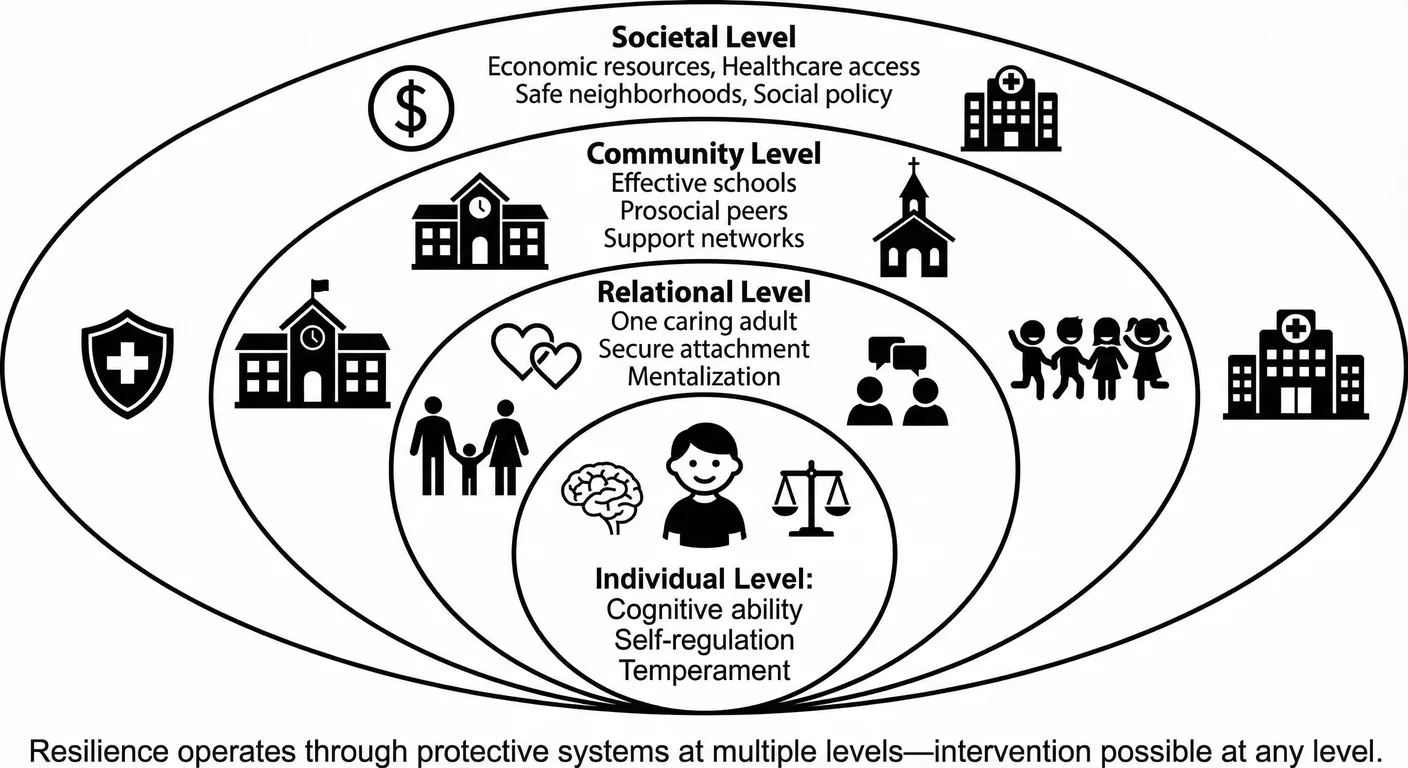

Resilience is not rare or exceptional—not magical. It emanates from the operation of ordinary human adaptive systems—attachment relationships, cognitive capacities, and self-regulation—that, when functioning adequately, protect development even under significant risk. It turned out we really are born that good, that strong.

Resilience is a process unfolding through transactions between individual characteristics and environmental contexts. The ‘magic’ lives in the child’s embracing the entire toolkit of redundant, well-honed adaptive systems characterising normal human development. When these systems function ‘well enough,’ they do a great job of absorbing and processing adversity; when they fail or are overwhelmed, pathology emerges and takes root.

This annoyed theorists and practitioners, while being theoretically and clinically revolutionary. If resilience emerges from ordinary rather than extraordinary processes, then interventions need not produce super children. Strengthening any of multiple protective systems—say by improving parenting, or ensuring stable adult relationships—could work. They could intervene by building self-regulation skills in the child and connecting families to community resources. These would all promote resilience. The child at high genetic risk for narcissism and also exposed to narcissistic parenting clearly remains vulnerable, but suddenly that vulnerability is conditional on whether basic protective systems function adequately—it is not destiny. All that needs to happen is for society to fulfil its duties and give that child a fighting chance.

Defining Resilience

After annoyance wore off, the industry went back to coining terms. Luthar 770 , in their critical evaluation and synthesis, defined resilience as ‘a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity.’

Two necessary conditions: Resilience, properly defined, requires both (1) exposure to substantial threat or severe adversity, and (2) positive adaptation despite that adversity 813 1070 .

That first condition, adversity, has to actually be there, as the term ‘resilience’ is sometimes misapplied to ordinary development in the absence of significant risk. It’s a positive presence of adversity—not the lack of a negative one. A child raised in a supportive, resourced family who develops well is not demonstrating resilience but expected normal development. To reiterate, resilience specifically denotes competent functioning despite conditions that typically derail development.

The second condition, positive adaptation, shows itself through age-appropriate developmental tasks: secure attachment in infancy, peer relationships and academic competence in childhood, identity formation and autonomy in adolescence, intimate relationships and occupational functioning in adulthood. Resilience means also maintaining competent functioning across these salient developmental domains, without demanding exceptional achievement.

Resilience as process, not outcome: So resilience is no longer a static trait or outcome but a dynamic process involving ongoing transactions between risk and protective factors across time 770 1072 .

A child may be resilient at one developmental stage (e.g., academically good in elementary school despite chaotic home environment) but struggle at another (e.g., relationship difficulties in young adulthood). Intriguingly, early struggles do not always preclude later resilience. Rutter 1070 introduced the concept of developmental ‘turning points’—life transitions or experiences that redirect trajectories, such as a supportive marriage, positive military service experience providing structure, or successful therapeutic intervention. His research showed that resilience processes can operate across the whole lifespan, not merely in childhood. This gave hope to many who thought their childhoods had written them off entirely.

Resilience is not the absence of distress: Resilient children are not unscathed. Werner’s 1313 longitudinal data uncovered that resilient adults from high-risk backgrounds reported more psychological distress and more relationship difficulties than their low-risk peers. This makes sense. What made them resilient, however, was their acceptance of struggle and courageous maintenance of competent functioning despite ongoing challenges.

Culturally embedded: Ungar 1262 , advancing a social-ecological model in 2011, pointed out that resilience is difficult to define without reference to the cultural situation. What constitutes ‘positive adaptation’ does actually vary across cultural scenarios. In some countries, individual autonomy and self-expression are markers of healthy development. In others, family loyalty and group harmony take precedence. Available protective resources (like extended family networks, religious communities, institutional supports) differ dramatically across those worlds.

The “Western” model of resilience emphasising individual agency alongside cognitive problem-solving and encouraging emotional expressiveness won’t capture resilience processes operating in communal cultures or under conditions of structural oppression 1262 . For the child, this cultural variability matters more than one might initially imagine. Resilience in one context will mean severing family ties and establishing independent identity (say, New York City). But a few miles away, for the same child, it means maintaining family connection while developing psychological boundaries within that relationship (say, Long Island in New York). Culture is not geography, nor ethnicity, nor even history; it comprises the actual values prevailing around us, that we live through.

The Empirical Foundation

Observable evidence comes from three key investigations that followed high-risk children into adulthood. Emmy Werner’s Kauai Longitudinal Study 1313 tracked 698 children born on a Hawaiian island from 1955 through age 40. One-third qualified as high-risk, experiencing four or more adversities by age two: poverty, or parental psychopathology, some family discord, and parental absence. This was objectively horrific and the best existing models confidently predicted uniformly poor outcomes. Approximately one-third of these high-risk children—72 individuals—nevertheless developed into competent, confident adults showing educational achievement and satisfying relationships.

What saved them? At the individual level, resilient children displayed temperamental ease: they were described as ‘cuddly’ and ‘good-natured’—precisely the low Negative Affectivity and high Effortful Control we discussed earlier. They showed adequate (not exceptional) cognitive abilities and what Werner termed ‘required helpfulness’—household responsibilities that built competence and provided satisfaction.

But the single most powerful predictor was relational: at least one stable, emotionally supportive relationship with a parent, grandparent, sibling, teacher, or mentor who provided what Werner called ‘continuous acceptance.’ At the community level, this often translated into involvement in church or youth groups, structured activities that provided belonging and additional positive adult connections. Society saw them and nurtured them; moving in to fill the gaps.

Norman Garmezy’s Project Competence 443 and Michael Rutter’s studies of Romanian orphans and Isle of Wight children 1070 had the same findings. Garmezy emphasised that protective factors operate through mechanisms: cognitive ability can protect because it enables recognition, hard as it is, that parental pathology reflects the parent’s disorder not the child’s failing. Being smart also led to accessing information about alternative ways of being and even planning escape routes. Rutter distinguished vulnerability factors from protective factors and noted that protection does not merely mean absence of risk: one good relationship within a high-conflict family is protective. The process succeeds through providing a relational haven amidst multiple relentless sources of unhappiness.

Rutter also identified that protective mechanisms operate most powerfully at those developmental turning points—transitions offering potential for change: this meant school entry, adolescence maturation, the leaving home threshold, entering marriage. At these junctures, even individuals on maladaptive trajectories can be redirected. Werner’s 40-year follow-up confirmed this: some who struggled in adolescence recovered through turning points with a supportive spouse, a new educational opportunity, and sometimes therapy. Resilience waxes and wanes depending on the balance between demands and resources at each life stage. Giving people open doors dissipates despair, and engages the inner urge towards progress and freedom.

The Architecture of Ordinary Magic

Masten 813 identified the adaptive systems constituting resilience’s ‘ordinary magic,’ and aligned them with Bronfenbrenner’s 161 ecological levels:

Individual-level protective factors:

Cognitive abilities, particularly problem-solving capacity, metacognitive skills—the capacity to think about one’s own thinking—and cognitive flexibility. These abilities enable the child to recognise parental pathology, adapt, and plan escape. The key finding: exceptional intelligence is not required; even modest cognitive capacity, when coupled with curiosity and persistence, can support adaptive functioning.

Self-regulation and effortful control, the capacity to modulate emotional arousal. To respond and not react, and therefore to inhibit impulsive responses, is paramount. The ability to sustain attention without reward, and therefore delay gratification. These temperamental capacities overlap substantially with Rothbart’s 1064 Effortful Control dimension. High Effortful Control lets the child partially compensate for inadequate parenting. The child can self-soothe when distressed. They will control themselves when provoked and can persist at tasks despite frustration, showing heart. The temperamental variability creating vulnerability in some children (low Effortful Control amplifies narcissistic parenting effects) also creates resilience in others (high Effortful Control absorbing those same effects).

Positive self-perceptions and mastery motivation, setting aside grandiose inflation for realistic self-efficacy built through genuine competence experiences. Realising parental opinions are not as solid as real-world achievement. The child who discovers they can master academic challenges or artistic pursuits has a pathway to growth. They discover they enjoy athletic skills or experience the glow of helping others and so develop a sense of independent agency: ‘I can affect outcomes; my efforts matter.’ This realistic effectiveness differs sharply from the narcissist’s grandiose fantasy: actual accomplishment grounds it. This inspires continued effort rather than defensive withdrawal when challenged.

Relational-level protective factors: The findings are thankfully consistent across studies: one stable, caring, available adult relationship, with parent, grandparent, aunt, uncle, teacher, coach, neighbour, family friend—buffers multiple risk factors 1313 443 1070 . This relationship need not be with the primary caregiver; actually, when the primary caregiver is the source of adversity (as in narcissistic parenting), alternative attachment figures become lifelines.

The protective adult offers emotional availability and validation, recognising the child’s authentic emotional experience, mirroring it back accurately, communicating ‘You are seen, you are real, your feelings matter.’ When the narcissistic parent cannot provide this validation, an alternative adult who does interrupts the developmental pathway to false-self organisation.

They also provide a secure base and safe haven—Bowlby’s 148 concepts apply to non-parental attachment figures. The child can explore challenging situations and take developmental risks when they know a supportive adult offers a base from which to venture and a haven to which to return.

Through modelling of healthy relatedness, the child of a narcissistic parent may gain exposure to relationships characterised by empathic reciprocity and repair after conflict. Witnessing such relationship dynamics with a teacher or coach—a grandparent—offers a template: “Relationships don’t have to be what I experience with my parent; other models exist.”

Finally, through cognitive reframing and externalisation, as the child matures and develops capacity for abstract thought, a trusted adult can help them mentalise the parent’s pathology: “Your mother’s rage is about her own shame, not you, little one. It was never about anyone else.” This externalisation prevents wholesale internalisation of pathological parental projections. Her mother’s worldview isn’t the whole worldview; it may not even be the main one.

Community and societal-level protective factors:

Effective schools provide not merely academic instruction but also structure, predictability, relationships with caring adults, opportunities for competence-building, and peer connections. For the child whose home environment is chaotic or emotionally barren, school may function as the primary developmental context supporting adaptive functioning.

Prosocial friend networks offer belonging and validation unavailable from family. Developmental tasks of adolescence (identity formation, autonomy, intimate friend relationships) can proceed successfully within these peer contexts even when family relationships remain impaired.

Religious and cultural communities provide meaning-making frameworks, moral guidelines, ritual structures, and adult mentors. For families facing multiple adversities, these communities may be primary sources of practical support, social capital, and hope.

Socioeconomic and structural resources, having adequate income, enough housing stability, proper healthcare access, and a feeling of neighbourhood safety. While these factors do not directly interact with the child, they materially affect parenting capacity and focus. Economic strain exhausts parents’ regulatory resources; unsafe neighbourhoods increase parental anxiety and restrict children’s exploratory opportunities; lack of healthcare means untreated parental mental illness and child developmental problems.

How Protection Becomes Biology

Our resilience has neurobiological mechanisms just as vulnerability does.

HPA axis regulation and stress buffering: Narcissism involves chronic HPA axis hyperactivation—the ‘vigilant brain’ showing elevated baseline cortisol, exaggerated stress responses, and impaired negative feedback. This brain signature is due to childhood programming caused by the unpredictable narcissistic parent. The child’s forced vigilance required to maintain the false-self and the terror of empathic abandonment change the child’s stress-regulatory system epigenetically.

Protective relationships exert counteractive effects. Children experiencing adversity (e.g., parental depression, marital conflict) who also have a warm, supportive relationship with one parent show cortisol patterns resembling low-adversity children. Those children denied that supportive relationship show HPA axis dysregulation 509 . The protective relationship reduces stress’s biological embedding without eliminating the stress.

The child still experiences the narcissistic parent’s failures, but the grandmother who provides predictable comfort, the teacher who offers reliable support, or the coach who recognises the child’s distress buffers that stress before it becomes fixed into their very nature. Loving protects and that protection lasts.

Prefrontal-limbic connectivity and emotion regulation: Narcissism involves reduced prefrontal-amygdala connectivity, crippling the top-down brakes on emotional reactivity. This neural circuitry is actually experience-dependent and sculpted by relational transactions during sensitive growth periods.

Chronic stress floods the stress hormone cortisol and impairs prefrontal cortex development while supportive relationships promote its growth. Fear literally stunts our children. However, children with strong attachment relationships show greater prefrontal-amygdala functional connectivity and attain better emotion regulation. Laboratory challenges directly reveal more adaptive stress responses 447 .

Not only is the world more emotionally real to them, they have greater traction over their emotions. They have better understanding of their experiences, and life becomes genuinely better to live through. The process involves both direct neurobiological effects (secure base experiences will reduce amygdala hyperactivation while allowing prefrontal executive centres to mature) and then skill-building (the caregiver who reduces stress also teaches regulatory strategies the child then internalises). These can be anything from reminding the child that people are fallible or that there are hopeful choices, and that splitting and absolutism isn’t how the whole world runs. For the child of a narcissistic parent, a compensatory attachment figure won’t fully remediate prefrontal-limbic dysfunction resulting from early attachment-based trauma. But even partial compensation, enough for sustained hope, strengthens regulatory neurology enough to prevent full narcissistic crystallisation—and enough for resilience.

Neuroplasticity and recovery: Neural systems, we now realise, retain plasticity across the lifespan, though plasticity decreases with age and early experiences do exert disproportionate influence 767 . This means, very rarely, limited protective interventions can partially change even well-established neurobiological vulnerabilities. Adult psychotherapy with narcissistic individuals has tried to leverage residual neuroplasticity: prefrontal-limbic remodelling; cognitive-behavioural work promoting flexible rather than rigid neural responses. This rarely works, however.

The Child’s Subjective Experience

For the child, protective factors are not abstractions. They are lifesavers. What child thinks, “My high Effortful Control is buffering my mother’s narcissism.”? They feel the actual terror of managing their distress when mother rages, finding solace in books or art, in imaginary worlds, connecting with the one teacher, or any person who seems to truly see them. The child does not “conceptualise resilience as process”; they experience surviving.

And their ability to use protective factors depends on their growth stage, not just the temperamental characteristics, and above all, the actual meaning they assign to their experiences. Remember that they are their own inner worlds, distinct from any other, and related to the rest of us through their experiences. What those experiences mean to them is everything. A three-year-old cannot cognitively reframe parental pathology; they can only experience the grandmother’s warm lap as refuge from mother’s cold withdrawal. A ten-year-old may begin recognising, “Mom gets mean when she’s upset about something else,” creating protective distance. A sixteen-year-old may consciously seek out the guidance counsellor, realising, ‘I may need help; my family is not like my friends’ families.’ Each developmental stage offers different protective possibilities.

Temperament guides which protective factors the child can access. The intellectually gifted, verbally precocious child may find refuge in reading, discovering through novels that other family configurations exist, that parents can be kind, that children can be valued for their authentic selves. Books become windows into alternative realities, ones their parents may not have realised exist, generating cognitive reframes before the child even has language for their parent’s pathology. The athletically talented child may find a coach who recognises their worth through their sports competence, their will to succeed thus building genuine self-efficacy that buffers hollow parental praise. The reality of training, improving, recognition and admiration from multiple sources can be reflected on when feeling the hollowness of the praise. It may be hollow because mother doesn’t understand and can’t see how real the achievement actually is. The musically gifted child may lose themselves in practice, achieving flow states offering temporary escape from home chaos while building discipline and mastery, and training their neurology to soak in the pure joy of integration and self expression. These domains of competence are not trivial hobbies; they are protective realities where the true self can exist and receive authentic recognition.

The child’s relationship to protective factors is also shaped by loyalty traps and survivor guilt. The child of narcissistic parents often experiences painful conflicts: accepting help from the teacher who recognises parental inadequacy feels like betrayal of the family; achieving success through their own competence triggers guilt (‘Why do I get to succeed when my siblings are suffering?’ or “If I’m competent, that proves mother’s claim that I’m the special one, but I hate being the only golden child, what about my little brother, my little sister?”). Protective relationships and experiences that threaten family loyalty or contradict internalised role assignments may be rejected rather than utilised. The scapegoat child offered genuine recognition may unconsciously sabotage that relationship, feeling it invalidates their identity, proves their parent right about how worthless and disloyal they are. The golden child achieving independent success may retreat into failure, unable to tolerate separation from the role conferring parental approval. They may also sabotage their future to try and give their siblings a chance at normality, at praise. All while experiencing passive aggressive hatred from them built up over years. Resilience thus requires not merely exposure to protective factors but the real capacity to accept and utilise them properly—in reality for every success there are countless near misses.

The timing and dosage of protection also matter. A single positive experience, a week at summer camp where a counselor showed kindness, will be insufficient if immediately followed by return to unremitting narcissistic parenting. The protective relationship must be stable and long-term to exert proper buffering effects. That’s actually rare. Grandparents living in the home, teachers the child has for multiple years, and ongoing relationships with coaches or youth group leaders confer more protection than transient connections precisely because the protective adult can be present across enough interactions and developmental challenges to become internalised as a secure base. The modern world is increasingly less built for those avenues.

Finally, the child’s experience of protective factors interacts with their growing understanding, and associated horror of their situation. Initially, the child may not recognise parental pathology as pathology; they experience it as just a reality. Mother’s rage is not “Mom’s narcissistic injury”; it is ‘I am bad.’ Father’s conditional approval is not “Dad’s inability to love unconditionally”; it is ‘Love depends on performance.’ Protective factors at this stage operate implicitly, neurobiologically, providing regulation and validation the child cannot yet conceptualise. As we grow we get access to other ways of being, either through school, our friends, our media, protective adults who spot something is wrong and try to help wherever they can, and an explicit recognition emerges: “Wait, other parents don’t act this way. Maybe the problem is not always me.” This insight is itself a powerful protective mechanism, but it is fragile, and depends on prior exposure to alternative experiences providing contrast, and vitally, time to reflect. The child raised in total isolation with only narcissistic parent as reference has no basis for comparison, no external perspective from which to recognise pathology. Protective relationships extending beyond the family become essential here: they provide the ‘view from outside’ enabling recognition that family dynamics are not universal laws, that the child’s experienced reality is specific, it is not, and never was, the only reality. Being there for this realisation with a child is one of the most powerful and moving moments one can experience.

The implications of the research are grounds of genuine hope. We don’t need exceptional children nor utopias. We need only normal protective systems working properly to have healthy societies. That’s achievable. Resilience is the outcome when protective factors successfully influence the vulnerability-adversity interaction—when relational and community-level systems function well enough they will prevent adversity from overwhelming children.

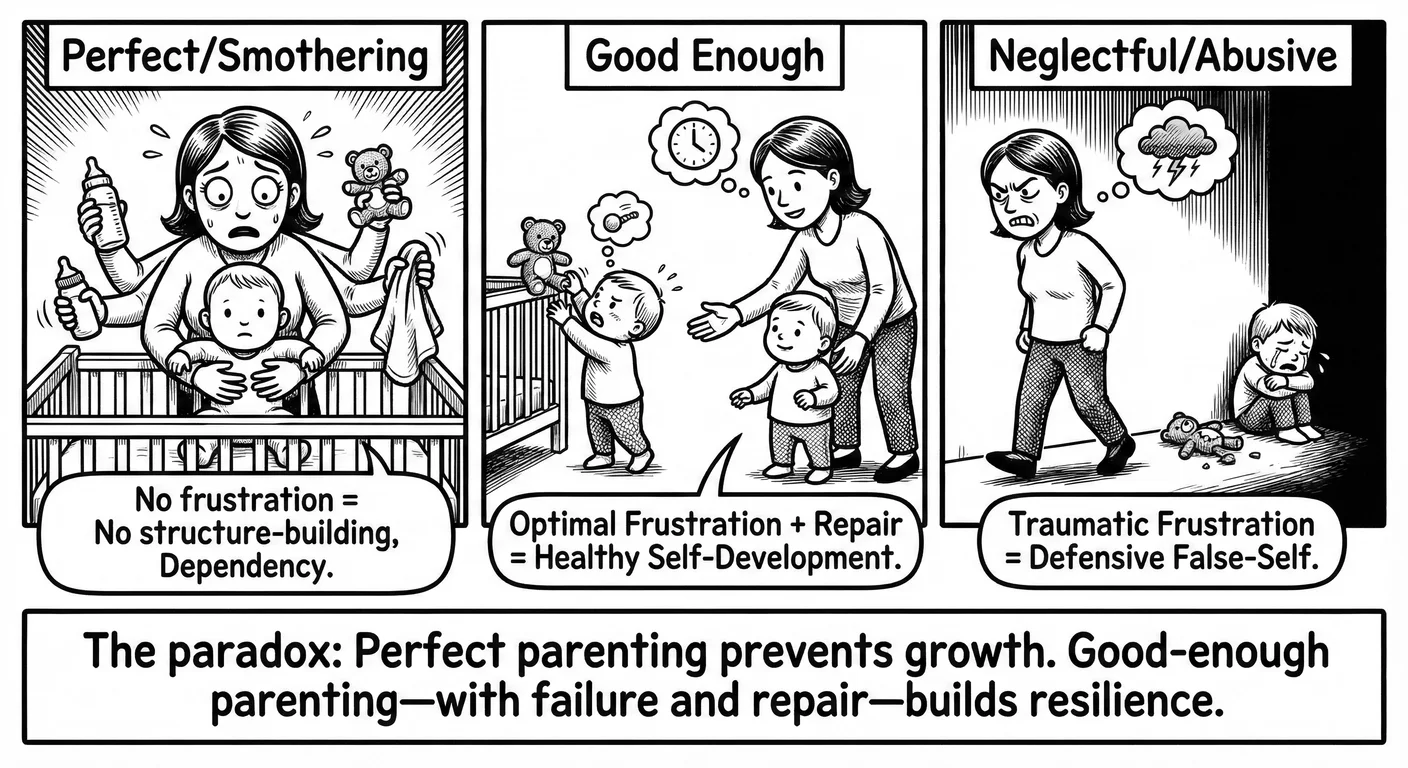

The Paradox of Imperfection

Winnicott’s 1331 ‘good enough mother’ concept tells us perfect parenting isn’t just unlikely but actively harmful to the child. The “good enough mother”—and Winnicott explicitly intended ‘mother’ as shorthand for primary caregiver, acknowledging that fathers or grandparents, other devoted adults, can fulfil this function—gives neither total gratification nor overwhelming deprivation but rather what Kohut 677 would later term: ‘optimal frustration’. This means reparable failures, tolerable delays in need satisfaction, and small disappointments that the child’s developing capacities can master. Each of these is due not to neglect or abuse, but to ordinary human lapses—say, forgetting to pick up mittens while on an airport run, or having to wait a few more minutes because the first round of toast was too burnt, or receiving a fried egg that is just a bit too solid, but still runny enough to appreciate. This works because instead of hurting, it grounds the experience as solid, in reality, one interaction at a time.

The developmental logic is equally elegant. In earliest infancy, the mother provides near-perfect adaptation to the infant’s needs. The newborn’s cry receives immediate response; discomfort is swiftly relieved; the mother functions as what Winnicott called the infant’s ‘subjective object’, experienced not as a separate person but as an extension of the infant’s direct will. This is actually fine: the little one has no real view of the rest of the world, and the cry for help and the response constitute the totality of their measure of reality. Meeting the vulnerable infant’s needs is perfectly healthy.

Yet Winnicott termed this the infant’s ‘moment of illusion’: the experience that the breast appears precisely when hunger emerges, that comfort materialises when needed, that the world directly conforms to desire. Winnicott thought the infant experiences, ‘I created this.’ However they could also be experiencing - ‘I love this. I should stick around.’ Winnicott believes this illusion of omnipotence is developmentally necessary—it delivers the infant’s first sense of agency, the proto-experience of effectance. While convincing this assertion of omnipotence on an empathic void is difficult to sustain logically, so we will circle back to it, and for now accept for scholastic purposes the thinking.

The good enough mother does not (actually can not) maintain this perfect adaptation. As the baby grows she begins—gradually introducing natural frustration to the child’s growing capacity—to fail the infant in small, reparable ways, not deliberately. She misreads a gesture, or perhaps is momentarily preoccupied as mentioned earlier. She cannot always provide immediate gratification because she is human and has needs of her own—bathroom breaks and sleep, to mention but a few—requiring the infant to wait temporarily. These failures are not catastrophic abandonment nor traumatic deprivation but ‘optimal frustrations’. They are manageable facts of a reasonable life that the infant’s developing self can understand, tolerate and process, and —and identify as innately human.

Through thousands of these micro-realisations, the little one accomplishes vital developmental tasks.

First, Winnicott’s disillusionment, although we prefer the term ‘recognition’: the infant realises mother is not an extension of the self but a separate person with her own reality and limitations. The breast does not magically appear; it arrives through mother’s agency, not the infant’s desire alone. By recognising her mother’s reality and limitations, the infant has a gradated gentle incline into grounding their own reality and learning about limitations and boundaries, and thus evoking the beginnings of self.

Suddenly her stomach doesn’t make mother appear for food. She will also turn to catch her mother’s eye because she loves mum and wants mum to see her, play with her.

Second, frustration tolerance: the capacity to endure delay to authentically self-soothe while waiting for reality. The infant who must wait three minutes for feeding begins developing the capacity that will, years later, enable the adult to tolerate setbacks and disappointments without fragmentation.

Third, internalisation: when the mother is briefly absent, the infant begins constructing internal representations—soothing memories and transitional objects, and their permanence—that provide comfort in her absence. The capacity for being alone and healthy, ironically, develops through experiences of good enough presence. Smothering exacerbates loneliness.

The good enough mother is not the ‘perfect’ mother. Winnicott’s clinical insight, drawn from decades of observing infants and mothers, was that mothers who attempted to achieve perfection—who could not tolerate their infant’s distress, who arranged to gratify every need instantly, who would not allow the infant to experience realistic frustration—got the results of maternal hubris, and also children with specific developmental arrests.

These children struggled (through no fault of their own) to separate self from other. They got frustrated easily, and had little inclination or skill in genuine independence. In short they were what was colloquially at the time called ‘spoiled’. They remained in fantasies of control or, defensively, in grandiose denial of need. Winnicott observed precisely this pattern in what would later be recognised as narcissistic personality disorder.

Beebe in 2014 97 , using frame-by-frame microanalysis of mother-infant interactions, showed that optimal infant development simply does not demand 100% attunement; the data proved it emerges when mothers are attuned around 30-50% of the time, with frequent mistakes followed by repair. Infants whose mothers were either perfectly synchronised (often reflecting maternal anxiety and over-control) or chronically misattuned showed poorer regulatory development. The Goldilocks range, good enough but not perfect, predicted secure attachment and effective self-regulation. This empirical finding vindicates Winnicott and Kohut’s clinical insights: structure emerges through manageable frustration and repair, not through idealised perfection. It also means children can love parents for being authentic people, and not idealised paragons.

Tronick’s Rupture-Repair Cycles: The Empirical Validation of ‘Good Enough’

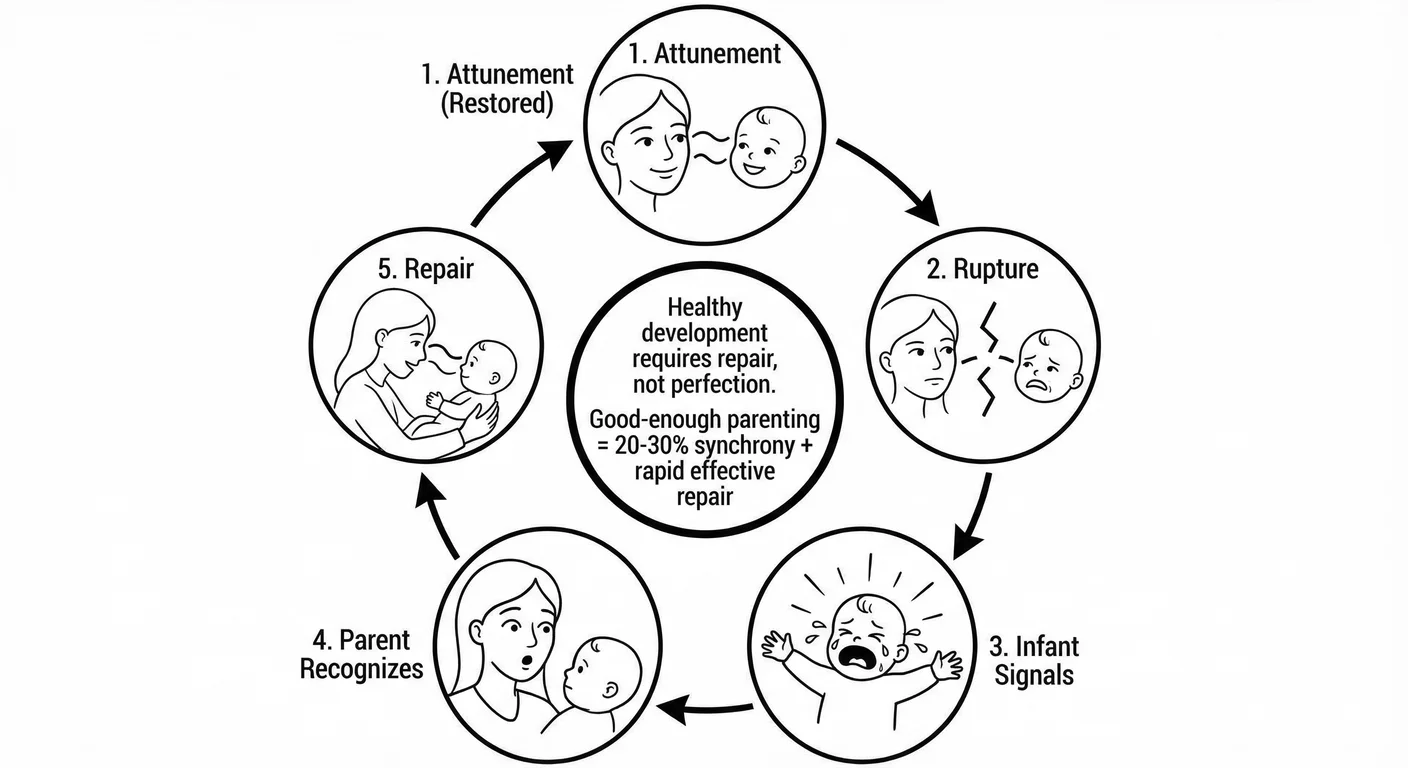

Tronick back in 1989 1238 , through his still-face paradigm and decades of developmental research, delivered the most direct empirical validation of good enough parenting’s protective powers. Tronick’s work showed that healthy parent-infant relationships are actually driven by cyclical patterns of interactive coordination (‘being in sync’), inevitable mis-coordination (rupture), and crucially, reparative re-coordination ( Rupture-Repair Cycle Rupture-Repair Cycle The natural pattern of disconnection and reconnection in healthy relationships. When ruptures (misunderstandings, conflicts, empathic failures) are followed by genuine repair, trust deepens and the relationship becomes more secure. ).

The still-face paradigm revealed the sequence experimentally. In the standard protocol, mothers and infants engage in face-to-face play, during which they achieve moments of joyful synchrony—mutual gaze, reciprocal smiling, coordinated vocalisations. This is genuinely delightful. The experimenter then instructs the mother to hold a ‘still face’, becoming emotionally unresponsive, maintaining neutral expression, ceasing all interactive engagement for two minutes. This is genuinely not delightful. The infant’s response is dramatic and distressing: initial attempts to re-engage mother escalate to distress signals, then self-regulatory attempts (looking away, self-soothing)—and ultimately, if the mother remains unresponsive, a collapse into withdrawal and despair. When the mother resumes normal interaction (the reunion phase), infants initially remain wary but, with maternal effort, gradually re-engage and return to coordinated interaction. The experiment is emotionally disturbing for baby and mother, most scientists, and most of the rest of us.

The still-face experiment does give us three life-changing findings however. First, even very young infants (as young as two months) expect interactive engagement and experience its absence as distressing. They truly feel the presence and love of their parents, and not merely as means of meeting drives. Second, infants actively attempt to repair interactive ruptures through escalating bids for connection—they are not passive recipients but active participants in relational regulation. That is agency. Third, and most relevant for good enough parenting, the capacity to repair after rupture is a normally developing competence that, when supported, builds resilience. We don’t just take things when born, we fix them, and ourselves to grow strong as well.

Tronick’s observations revealed that even in healthy, securely attached dyads (when two individuals interact), mother and infant are in synchronised coordination only about 20-30% of the time. The remaining 70-80% involves micro-misattunements—mother looks away when infant seeks gaze; infant becomes fussy when mother is playful; timing is slightly off; emotional tone is mismatched. Critically, these misattunements are not pathological. They are the ordinary fabric of everyday life.

What distinguishes healthy dyads is the rapidity and effectiveness of repair of naturally occurring setbacks, not their lack—just as walking on uneven ground improves our balance. The good enough mother recognises the mis-attunement (registers infant’s distress or withdrawal) and initiates repair—reestablishing eye contact and adjusting her emotional approach.

It is the conscious awareness of repair on both sides that rounds out the interaction and provides the security and trust both sides need.

Tronick’s 1239 longitudinal studies tell us that infants who experience frequent rupture-repair cycles actually develop better self-regulatory capacities compared to infants experiencing either chronic misattunement without repair or artificially perfect synchrony. The rupture-repair gives us further knowledge: (1) interactive disruption is survivable and temporary; (2) the self and other can tolerate asynchrony without relational dissolution; (3) misattunement can be recognised and repaired, meaning metacognition occurs in both mother and child; (4) autonomy coexists with connection—the infant can signal distress and trust the caregiver to respond. These are the exact capacities absent or impaired in narcissistic personalities; their interpersonal ruptures trigger catastrophic shame or rage— and repair feels impossible because the underlying capacity to trust in relational resilience was never established, or more accurately denied and therefore atrophied.

Follow-up studies confirm the long-term protective effects. Priel 1007 in 2005 found that infants with mothers demonstrating high rupture-repair competence showed more secure attachment at 12 months, and then better emotion regulation at 24 months, and far fewer behavioural problems at school age compared to infants whose mothers either maintained artificial perfection or failed to repair misattunements. The good enough mother’s willingness to fail and then repair protects more powerfully than impossible perfection.

Reflective Functioning: The Cognitive Mechanism of Good Enough Parenting

More recent work 404 in 2016 on parental reflective functioning (PRF for short) gives us a handle on the cognition behind good-enough parenting. Reflective functioning—the capacity to visualise mental states in oneself and others, recognising that behaviour springs from internal experience—embodies a core human capacity.

When applied to parenting, PRF lets the parent hold the child’s mind in their mind. They understand that the child’s behaviour truly arises from internal experiences rather than from deliberate provocation or defiance. It is not there as a confirmation of parental adequacy or inadequacy. In other words, parental reflection signifies nothing less than parental empathy.

The parent with good PRF observing their toddler’s meltdown thinks, “Of course she’s overwhelmed—the transition happened too quickly and she’s tired. I am a bit too.” rather than, “She’s manipulating me,” or “I’m a terrible parent.” The parent recognising their adolescent’s surliness thinks, “Aye, he’s struggling with a friend’s rejection and taking it out on me because I’m safe,” rather than, ‘He hates me,’ or “I’ve failed to raise a respectful child.” The ‘aye’ and ‘of course’ are essential, though often unmentioned. That agreement signals the initial recognition as insight arrives. The rest of the sentence is verbal rendering. PRF is an agreeable state, and an example of how agency changes with insight as well as environmental factors.

PRF gives the parent their own perspective with some hope of being within a stone’s throw of objectivity, or at least grounding. Recognising the child’s emotional journey as separate from the parent’s journey is key in this, ensuring neither merge anxiously (‘Your distress is my distress; I must eliminate all discomfort’) nor fall into the shortcut of defending rigidly (‘Your distress is unacceptable and must be suppressed’).

Slade 1148 tried to formalise PRF in 2005 through the Parent Development Interview (PDI), which assesses parents’ capacity to reflect on their child’s internal experience and their own parenting. Research with the PDI has shown that parental reflection powerfully predicts parenting quality and child outcomes. That same year, Grienenberger 491 found that mothers with high PRF showed more sensitive, attuned interactions with their infants, were more likely to repair ruptures effectively, and had infants demonstrating more secure attachment. Mothers with low PRF, struggling to recognise their infant’s mental states, often projecting their own feelings onto the child or responding to surface behaviour without understanding underlying experience, showed disrupted communication, more frequent unrepaired ruptures, and infants developing disorganised attachment. While this is impressive to confirm scientifically, it may not be entirely speculative to say parents have had some intuitive grasp of this throughout most of human history.

More personally, PRF helps the good-enough parent recognise and tolerate their own failures. The parent with mentalising capacity can reflect, “Ah yeah, I snapped at my child because I was stressed about work, not because she was misbehaving. She’d no idea. Oh gosh. She probably felt hurt and confused. I need to fix this.” This self-reflective capacity supports acknowledgement of error. That acceptance opens the door to taking responsibility and initiating repair quickly and sincerely—this is precisely the sequence absent in narcissistic parenting.

Cooke 263 examined 47 studies on PRF and parenting behaviours in infancy and early childhood. Higher PRF strongly predicted more sensitive responsiveness, less harsh discipline, more effective limit-setting, and more successful rupture-repair sequences.

At its heart, it allows a parent to separate the child’s actual communication of their inner world from the distorted projections of the parent’s own past experiences. By reflecting on behaviour as a meaningful form of communication rather than any kind of threat, parents can stay emotionally grounded, even joyful, in the most difficult of parenting moments.

This clarity assures care is guided by the child’s genuine needs rather than the parent’s own anxieties or desire for self-validation. A reflective stance provides the humility necessary for the “repair”—a quality a narcissistic parent simply doesn’t have. It accepts that failures in connection are as inevitable as the occasional dropped call, and the strength is in a parent’s ability to recognise those lapses and move towards an honest fixing until the forward flow is restored.

The Protective Mechanism

The good enough parent enables the true self to develop rather than be buried. Winnicott 1331 characterised the true self—that spontaneous, authentic core of subjective experience and agency—from the false self, which is a defensive, compliant façade constructed when the environment fails to recognise or encourage the true self. In optimal development, the good enough mother does recognise and respond to the infant’s spontaneous gestures and authentic needs. She sees her child. The infant reaching for a toy experiences the parent facilitating that reach; the infant crying in distress receives soothing; the infant showing delight is met with mirrored actual delight. These ‘attuned’ responses, occurring often enough but not perfectly, communicate: “Your authentic self is real and worthy of response, and I have limits and a separate reality. But you matter. You exist; I exist—we exist together.”

The narcissistic parent, predictably, ignores the child’s authentic gestures to instead focus on their own narcissistic needs. The child must be perfect, special, an extension of parental grandiosity and provide supply. Otherwise, what is the point? The child’s spontaneous self is ignored or contingently approved only when it aligns with parental requirements. If not, then it is interference, or worse, competition. The child’s true self, unrecognised, has no choice but to go underground.

The child first constructs an imaginary self, one that reflexively secures attention and starts using it as a shield until it becomes the false-self (the perfect child, the child who never authentically needs) calibrated to secure parental recognition. Good enough parenting prevents this split by recognising the authentic child, ensuring their true self remains viable.

The good enough parent enables frustration tolerance and realistic self-appraisal to develop. Through optimal frustration, the child learns that need does not guarantee immediate gratification, that others have separate realities and limitations. This means that the self (their own or that of their parent) is neither omnipotent nor worthless but realistically capable within constraints that make sense and are able to change, to harmonise with reality. The toddler who must wait just a few minutes for mother’s attention begins building the capacity to tolerate delay. The preschooler whose parent gently corrects a mistake (“That tower fell because the blocks weren’t balanced; let’s try again”) learns that failure is informative feedback, not catastrophe. The school-age child whose parent acknowledges genuine achievement without inflation (‘You worked hard on that project and it shines through’) develops realistic self-esteem grounded in actual accomplishment. These moments are integrated and form part of a responsive self instead of being encoded as self-defence schemas.

The narcissistic parent by comparison provides either traumatic frustration (rage and contempt when their child fails to meet impossible standards) or no frustration (hollow praise and gratification of all demands to maintain the child’s—and through identification, the parent’s—grandiosity). Neither provides any realistic self-appraisal, denying the little one the essential material for building a real, resilient self. The child never learns frustration tolerance because frustration is either threatening or nonexistent. The resulting narcissistic adult finds criticism or limitation intrinsically intolerable because these experiences were never integrated into manageable, informative feedback. Good enough parenting prevents narcissistic fragility by building character.

The good enough parent models repair, teaching that rupture is not the end and relationships are resilient. Tronick’s research tells us definitively that the rupture-repair cycle is an engine of relational competence. “The relationship can tolerate disruption. I can be angry or hurt, and mother will not abandon me nor retaliate. She will discover her error because she loves me and reconnect—we’ll be okay.” This internalised template enables the adult to navigate inevitable relationship conflicts without anxiety spikes or defensive rage.

The narcissistic parent is stuck. They cannot model repair because repair means first acknowledging failure. The narcissistic parent’s fragile self-structure cannot accept imperfection or fallibility, so this path is impossible. When the narcissistic parent fails her child, that failure is denied or, worse, projected onto the child.

There is no felt need for repair, leaving only doubling-down on the false narrative. This foreshadows gaslighting (“I never yelled at you; you’re too sensitive”) or counterattack (“If you weren’t so difficult, I wouldn’t get upset”). The child learns: “Rupture is destruction. Relationships are fragile and brittle. I can’t make mistakes, I can’t show need. I must never provoke abandonment.” This terror of rupture and lack of repair permeates narcissistic relationships all the way into their adulthood. Good enough parenting prevents this through thousands of rupture-repair cycles by showing that relationships are strong and failures are survivable.

The good enough parent’s reflective functioning enables the child to develop their own mentalisation capacity. Fonagy’s 404 research showed that PRF is transgenerationally transmitted: parents who mentalise their children raise children who develop mentalising capacities. The mechanism involves the child internalising the parent’s reflective stance. When the parent says, “You’re crying because you’re disappointed that we can’t go to the park today; it’s hard when plans change,” the child learns (1) behaviour arises from internal states, (2) internal states can be named and understood, (3) emotions are meaningful but not overwhelming, and (4) another person can understand your mind without merging with it. When they encounter these situations as they grow they learn to recognise. They begin to develop their own capacity to mentalise and so to reflect skillfully on their own internal experience, then progress learning to understand others’ perspectives, and to channel emotions through cognitive expansion.

The narcissistic parent with impaired mentalisation cannot therefore teach the child to mentalise. The parent projectively identifies—experiencing the child’s emotions as their own failure or projecting their own intolerable emotions onto the child—while remaining cognitively distant. They become a dark mirror responding to surface behaviour without recognising internal experience.

The child never gets to learn that minds can be known under that surface and separate selves are healthy. When the child grows into the resulting narcissistic adult they also show the characteristic failures of mentalisation, including specific difficulty recognising others’ separate subjectivity, due to bypassing the development of empathy. This leads to compromised emotional regulation due to their inability to mentalise emotional experience.

Good Enough Feels Better Than Perfect

For the child—the subjective, experiencing child—good enough parenting has a distinctive experiential quality. They experience the lived texture of being truly known and missteps repaired. The world becomes corporeal and “lived in”.

The toddler seeking mother’s attention experiences: “She saw me (mirroring). Then she turned away to the phone (frustration). I felt upset (emotional response). I cried louder (escalation). She looked back, put down the phone, said ‘I’m sorry, sweetie, let me finish this call and then I’m all yours,’ and two minutes later picked me up (repair).” This sequence, repeated across development, is just one example of tolerable frustration and reliable repair. The child feels, “She comes back. She cares. I can wait. The upset feeling goes away. We’re okay.”

As the child matures, the subjective quality evolves. The school-age child of good enough parents thinks, “Mum got mad at me for not doing homework, but then we talked about why I was avoiding it, and she helped me make a plan. She wasn’t perfect, she yelled first, but she apologised and we fixed it.” The adolescent thinks, “My parents have limits and flaws. They’re not heroes, but they’re real. They try. They mess up. They own it. I can be real too. This world is built by and for people like us.” This realistic appraisal of parents, neither idealised nor devalued, enables the child to develop a realistically open sense of self and others. This very capacity is absent in narcissism’s splitting dynamics (all-good vs. all-bad; grandiose vs. worthless).

The good enough parent’s failures, paradoxically, feel safer than the narcissistic parent’s pseudo-perfection because they are human failures accompanied by acknowledgement and repair. They are not automated performance adhering to an arbitrary schema. The child realises: “People fail. It’s survivable. Failure doesn’t equal worthlessness. Even if it is, it’s temporary. Relationships withstand rupture.” These realisations, unspoken, become the foundation for adult relational resilience. The child raised by good enough parents may struggle with relationships (it does not eliminate all difficulties) but they possess the core capacities for repair and frustration tolerance that enable them to work through challenges rather than fragmenting into narcissistic defensiveness.

The implications are quite hopeful. This doesn’t require extra resources or perfect self-awareness from the parent. It requires only, wonderfully, ordinary human capacities. One just needs the ability to see the child as a separate person and to attempt repair after failures. The parent must also notice those failures. These capacities are trainable and accessible to most parents most of the time. The child at genetic risk for narcissism who will be exposed to various environmental stressors will remain vulnerable. But when that child encounters a parent who is good enough—imperfect but reflective, relentlessly repairing—the trajectory towards narcissistic personality organisation is stopped. The maze need not be built because the wound was adequately tended. Not perfectly. But good enough.

When Parents Fail

But what happens to the child whose primary caregivers do crash out? For children raised by narcissistic parents who provide neither mirroring nor secure base, resilience won’t be from parental adequacy. Yet Werner’s Kauai study revealed another lifeline: even children experiencing severe parental failure developed adaptive outcomes when one caring adult—a grandparent, teacher, mentor, coach—provided what Bowlby 148 termed a ‘compensatory attachment relationship.’

We met Michael in the opening vignette. Another child, Mary, whose parents were both chronically mentally ill, formed a close bond with a teacher who recognised her intelligence and offered a relational template radically different from her chaotic home.

These caring adults did not rescue children from adversity nor provide substantial material resources. They offered something more—being seen and understood—that primary caregivers did not provide.

Research 499 shows children form quite distinct attachment bonds with multiple figures, and these very different channels contribute independently to outcomes. A child with insecure maternal attachment but secure attachment to grandmother shows trajectories resembling securely attached children. A recent review 284 concludes that even one secure attachment within a network of predominantly insecure attachments significantly protects the child. The child does not need to replace the narcissistic parent; they need only one person who sees them authentically. That one person can ground them in reality, and most kids will take it from there.

The process works through what Alexander 16 blandly termed ‘corrective emotional experience.’ The child conditioned to expect that vulnerability triggers parental rage takes a leap of faith, risks authentic expression with the caring teacher—and discovers that vulnerability elicits support. The child who learned that mistakes provoke devaluation makes an error in the mentor’s presence—and finds that failure prompts encouragement. Or even better, that it’s no big deal. These expectation violations destabilise pathological internal working models. The child begins to hope.

The ‘compensatory’ caregiver creates a relational space, a pocket world, where the child’s true self can emerge. For the child, this becomes: ‘With Grandma, I can be sad; with Coach, I can make mistakes. And things are still fine—this is real.’ The true self, rather than being constantly extinguished by narcissistic parenting, finds refuge—preserved until the child achieves sufficient autonomy to reclaim their authenticity throughout the real world. Childhood wasn’t Ragnarok; just a winter that passed.

But limitations do apply 1032 : any such relationships lasting less than six months produce negligible or even negative effects—premature termination reinforces the reality of abandonment even more keenly. Compensatory relationships can protect from, and sometimes even mitigate, but they can rarely eliminate damage. It’s not like in the movies. The adult who survived narcissistic parenting through a caring grandparent will definitely describe that relationship as life-saving—but still, they carry wounds from the parent who should have loved them but did not. Nevertheless, the social implication is clear: we need only ensure that every child has access to at least one caring, consistent adult who sees them authentically. That is achievable.

Individual Resilience Factors: What the Child Brings

What happens to the child is only part of the story, but what the child brings to their world is the greater part. Children are active agents whose individual characteristics—cognitive abilities, temperamental attributes, and self-regulation—make all the difference in how adversity registers and whether they fall towards narcissistic organisation or soar into healthy adults.

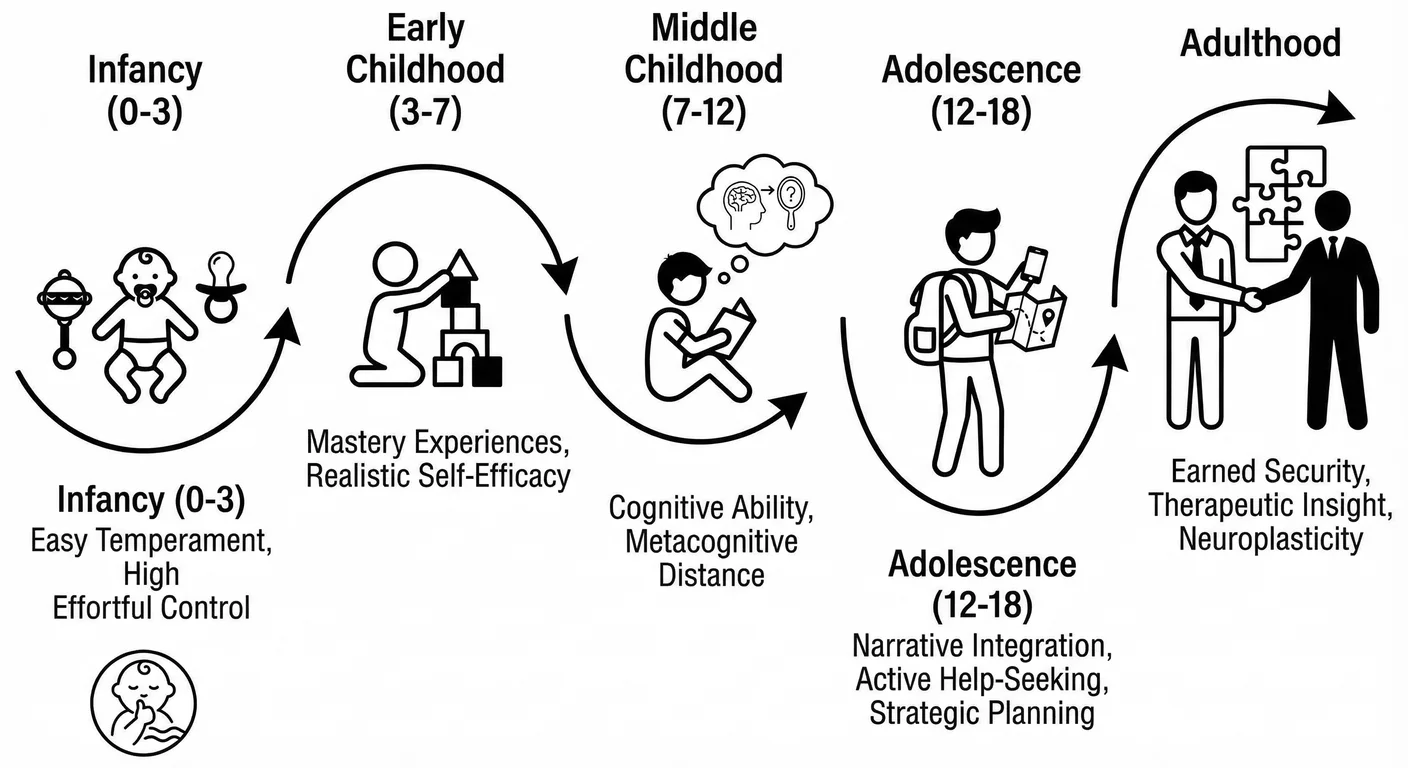

The Developmental Arc

In infancy and early childhood, temperament dominates. Nature provides temperament and says ‘here you go,’ and the world says ‘let’s roll the dice and see what happens.’ The ‘easy’ child 1224 —with positive mood and high adaptability—will get less negative parenting even from narcissistic parents. Less criticism from the world means less injury, after all. A 2011 meta-analysis 67 found these kids receive less harsh treatment across all family situations. A protective feedback loop emerges: easy temperament → less parental rage and withdrawal → better outcomes. Nature blesses, and the world ends up testing the child a little less.

Another child with high ‘effortful control’ 1064 can self-soothe well enough during parental abandonment and endure frustration when attunement fails; they learn to manage intense emotions without external support. The Dunedin 221 study revealed that children with this innate self-control predicted adult health and wellbeing in a dose-response gradient—which means self-control’s protective effects were strongest for children experiencing adversity. Nature made them a little stronger; the world kept sending bigger monsters, and these children kept defeating them and levelling up. This is heartening.

As children become more aware in middle childhood, that intelligence becomes protective through specific faculties they develop 770 . The bright child achieves ‘metacognitive distance’: ‘Dad’s rage when I got a B is crazy. Other kids’ parents don’t act this way. Maybe the problem is his reaction, not me.’ This won’t dismiss emotional pain but does prevent blind internalisation. If it’s not always their fault, reasons exist, and they can find answers.

The smart child also accesses alternate worlds—reading books, watching other families, comparing and thinking, forming ideas that reveal parental responses as unusual rather than universal. Luthar 771 documented that high-IQ children in dysfunctional families were far more likely to seek mentors and pursue therapy as adolescents. They wanted to talk to people who could guide them out of the maze.

By their teens, inner storytelling surfaces as powerful protection. McAdams 826 demonstrated teens writing ‘redemptive narratives’—stories acknowledging suffering but framing it as catalyst for growth—show better psychological adjustment than those with ‘contamination narratives’ where suffering defines everything, and purity lost is the arc. The teen who wonders, ‘My Mum is narcissistic and hurt. I’ve found some people now who help me see more. I’m building a life beyond that hurt,’ demonstrates the ‘narrative integration’ that protects against narcissistic attacks. This is not rationalisation, nor excusing the violations or abuse. On the contrary, Main 784 identified ‘ Earned Secure Attachment Earned Secure Attachment A secure attachment style developed through healing work and healthy relationships in adulthood, rather than being formed in childhood. It demonstrates that insecure attachment patterns can be changed. ’ because of these children’s acceptance of the truth and their mature response. They go on to become adults who have experienced difficult early relationships but achieved genuine security through coherent, grounded narrative processing. Their inner stories help build a world that makes sense, and is suffused with solid truth, and not gaslighting.

Adolescence is the peak period for individual resilience factors. Brain growth, surging neuroplasticity, and intellectual growth in multiple directions power the systematic de-idealisation of parents. They want out of the prison: some engage in active help-seeking, and some even start strategic planning for escape. Self-discipline motivates these children, resulting in sustained academic striving that opens up their exit routes. Narrative capacity leads to redemptive insights that form their futures. The 17-year-old recognises: ‘My parents are messed up. It hurt me. But I am going to college, I will be getting therapy, and not letting them define my whole life.’

In adulthood, neuroplasticity offers continued possibility. Siegel in 2012 1141 provided hope to us all by showing the brain retains modifiable capacity across the lifespan. The prevailing understanding until his work was that this capacity evaporated in the mid-20s to 30s. People can actually change, if they can get past themselves. That caveat becomes more important as we age. The therapeutic relationship also provides a corrective attachment experience: the narcissist expects criticism when vulnerable; the experienced therapist responds with genuine empathy. These repeated expectation surprises activate neural circuits enabling more flexible, less defensive functioning. It can take years, and only if the narcissist sticks around. Main 784 found that approximately 20-25% of adults shift attachment status over decades, with shifts to earned security occurring in those who engaged in long-term therapy and formed stable partnerships. For a lot of very hurt people, getting those factors in place is simply beyond reach.

Limitations and the Subjective Experience

The hard truth is that individual factors are neither necessary nor enough for resilience. The gifted child of severely abusive parents remains at substantial risk; intelligence tilts probabilities but offers absolutely no guarantees. The world rolls the dice every day on that child’s fate. Easy temperament may reduce intensity of pathology but won’t eliminate the harm—and the compliant, adaptable child may have to sacrifice true self-development through over-accommodation just to survive the abuse.

Yet throughout their childhoods, kids discover that their inner world provides some agency over outcomes. The 7-year-old notices: ‘When Mom says I’m stupid, it hurt. But I know I got an A. She saw it. She’s wrong.’ The 13-year-old thinks: ‘When Dad rages, I can go to my room and it’s quiet there, I can calm myself down.’ The 35-year-old in therapy feels: ‘Wow. For the first time, someone sees me without needing me to be perfect.’ This becomes realistic self-esteem, grounded in truth that can be reached for whenever, and by whomever, rather than narcissistic grandiosity which is imaginary and always a bet placed against the truth. Suddenly these people can acknowledge wounds while refusing to be solely defined by them.

Conclusion: The Wound and the Maze

The developmental pathway to narcissistic personality disorder emerges clearly. Narcissism is neither genetic destiny nor bad parenting alone—it’s what happens when cumulative risk overwhelms our natural protection during the years that matter most. Risk factors and protective mechanisms together show that early intervention can interrupt the pathway before NPD structures harden into permanent disorder.

But, when we look around, and see the damage in our lives, and going on around us, is that enough?

The most controversial implication: when prevention fails and narcissistic personality disorder consolidates by early adulthood, what remains is not a person in any meaningful non-legal sense. It is a narcissistic situation—an autonomous reactive system operating in the absence of the authentic self it was supposedly constructed to protect. The narcissistic fortification prevents access to the inner authentic self, and—critically—that authentic self was either never developed or was extinguished a very long time ago in childhood. Therefore, all we experience from all sides is the mechanised fortification. The individual is no longer a he or a she; we only see the ‘it’ of the narcissistic situation.

This defensive system hijacks the very attachment mechanisms evolution designed for human connection. It systematically trains victims through operant conditioning and trauma bonding to provide validation while believing they are engaged in authentic relationship. The narcissistic disorder at work, not the person—the disorder pretending to be the person through the false self.

The Labyrinth Without a Centre: Understanding Narcissistic Absence

How then can the narcissist reason and act? They do not have a self, however they do have agency. Working through the research, we notice that individual patterns of agency are modified and modulated by situational narcissistic patterns. This is as apparent in borderline-NPD interactions, as it is in narcissistic parent-child interactions, and also with NPD-social interactions. They provide models of agency that are integrated in two dramatically different paths. One path leads to the fluid agency states that comprise the ‘unstable self’ of borderline. The other is a series of overlapping reactions that harden into place as the apparent false-self of the narcissist. This is diamorphic agency masquerading as self.

Kernberg 649 described the narcissistic personality as a ‘grandiose self’ compensating for underlying fragility. Kohut 674 saw it as arrested development—the self failing to cohere around stable representations. Both frameworks converge on a reality confirmed by decades of clinical observation: at the core of consolidated narcissistic personality organisation lies not a wounded child awaiting rescue, but absence. The place where an integrated, authentic self would have developed—had early relational conditions permitted—is empty. There is no one home.

The metaphor of the labyrinth captures this architecture precisely. Greek mythology tells of the labyrinth housing the Minotaur at its centre—a monster to be vanquished, a prize to be claimed. The therapeutic impulse when encountering narcissistic personality disorder is to navigate the maze of defences and endure the cycles of idealisation and contempt, believing that persistence will eventually reach a wounded core amenable to healing.

But the clinical reality tells a different story, and has done so — consistently — for decades.

The labyrinth is the personality. No child, no authentic self waits at the centre. The maze structure—the grandiosity, the rage, the absence of empathy—protects nothing. It is everything. The labyrinth leads only to more labyrinth, corridors of defence opening onto further defences, all organised around an absence where selfhood should be.

This is not metaphor but phenomenological description grounded in attachment theory, object relations, and neurodevelopmental science. Narcissistic parents fail to provide the mirroring necessary for the child to develop what Winnicott 1331 termed a ‘true self’—an authentic core organised around the child’s actual emotional experience. Instead, the child develops a ‘false self’: a compensatory structure organised around parental expectations and the imperative to be exceptional rather than real.

In normal development, false-self adaptations are temporary. The child switches between authentic and adaptive presentations while maintaining internal continuity. But when parental invalidation is severe and coupled with vulnerability, the true self never consolidates. It is not hidden or defended—it fails to develop at all.

What remains is pure defensive structure. Grandiosity without genuine competence, relationships as validation extraction rather than human connection.

The defensive operations catalogued throughout the research—projection, splitting, idealisation-devaluation cycles, gaslighting, rage as regulation, exploitation as relating—do not protect some unseen authentic self from overwhelming shame. They are the personality, operating reactively to maintain the defensive structure itself.

The narcissistic situation (we deliberately avoid gendered pronouns; the system operates identically regardless of biological sex) does not relate—it extracts supply. It does not love—it idealises when useful and discards when not. It does not feel shame and defend against it—it is the defence, autonomous and self-perpetuating.

A labyrinth that reactively builds more labyrinth to obscure the central emptiness.

The mechanisms through which narcissistic situations operate—trauma bonding, intermittent reinforcement, gaslighting, attachment hijacking are explored later. Here, what matters is the developmental implication: every prevented case of NPD prevents not only one individual’s suffering but the creation of a system that will go on to traumatise dozens of others across a lifetime.

Prevention is not just kindness. It is containment.

The Maze Is Not the Wound

Clinical discourse about narcissistic personality disorder often emphasises compassion: ‘beneath the grandiosity is a fragile, wounded self.’ This framing works for individuals with narcissistic traits—those who retain capacity for authentic relating and vulnerability when safety allows. But when applied to consolidated narcissistic personality organisation, the ‘wounded child’ narrative becomes a cognitive trap. It sustains futile therapeutic efforts. It prolongs survivors’ entanglement. It is compassion weaponised against clarity.

The maze is not protecting the wound. The maze is the personality. Grandiosity, exploitation, absence of empathy—these are not defences obscuring an authentic self; they constitute the entirety of individual subjective experience. The narcissistic organisation does not hide vulnerability; it experiences grandiosity as reality. It does not repress empathy; it lacks the internal neural structures that would generate empathic awareness. It does not defend against authentic connection; there is no authentic self to connect from.

This distinction carries clinical and practical implications. Individuals with narcissistic traits—authentic self present but defended—differ markedly from consolidated narcissistic personality disorder, where defensive operations constitute personality. Therapeutic possibility exists where authentic self remains accessible. It diminishes where defensive structure has become total and encompassing.

Similarly, relational bonds based on mutual recognition differ from supply dynamics maintained through trauma bonding and intermittent reinforcement. One is a relationship. The other is a harvesting operation.

The Mechanism of False Self Creation: Diamorphic Agency

What happened to Lucia? Her agency—her capacity to want, to choose, to act from her own centre—didn’t simply diminish. It changed shape. It morphed to fit the container her mother’s pathology provided.

The term diamorphic agency describes this phenomenon wherein the self is not merely influenced by the other, but structurally reconfigured by them. Just as a gas will expand or contract to fit its container, human agency morphs to fit the constraints of its dyadic container.

In this state, the individual’s agency does not simply increase or decrease in volume; it changes shape (morphs) and is structurally altered to fit around situational factors. Specific agentic functions (e.g., critical thinking and self-regulation) are either hyper-activated or suppressed to maintain the homeostatic equilibrium and coherence of the relationship.

Mechanisms of Agency Morphing

1. The Principle of Complementary Schism. Diamorphic Agency relies on the systems theory concept that a dyad tends to split into complementary roles to function. If Person A morphs into a shape of Hyper-Agency (dominance and grandiose certainty), Person B is unconsciously compelled to morph into a shape of Hypo-Agency (compliance and self-doubt) to prevent systemic collapse. The “shapes” are diametrically opposed but mutually reinforcing. The insight here is that pre-existing roles and inertial power dynamics provide the system, the environment, enabling this shift in agency.

2. The Locus of Regulation. Individual Agency: The locus of regulation is internal (I decide what I do). Diamorphic Agency: The locus of regulation becomes intersubjective. The “Morphed” agent scans the other partner to determine their own permissible range of action. The agency is no longer self-determined but is “rented” or “licensed” from the dyad. This extension accounts for multiple presentations of abuse dyads across the research.

3. Institutionalisation (The “Frozen” Dyad). In systemic contexts (corporate and political, even legal), Diamorphic Agency is codified through external instruments—contracts and treaties, franchise agreements. These instruments serve as a prosthetic structure that permanently locks the diamorphic shapes in place, or at least ‘starting positions’ preventing the agency from “morphing back” into its natural individual state even when the parties are apart.

In high-control corporate structures or narcissistic relationships, we observe a ‘static diamorphism’—a permanent distortion where one party assumes the shape of the Architect (all will, no consequence) and the other is forced into the shape of the Instrument (all consequence, no will). This explains why intelligent, capable individuals (franchisees, partners of narcissists) often appear ‘paralysed’ or ‘irrational’ to the outside world; they have not lost their agency, but rather, their agency has been diamorphically specialised for a role that no longer serves their own survival, but the survival of the dyad.

Functional vs Pathological Presentations

Type I: Fluid (Functional) Diamorphic Agency. A temporary and reversible morphing of agency for the purpose of mutual efficiency or survival. Role flexibility characterises this type: the “Leader” and “Follower” shapes are costumes worn for a specific task (e.g., a surgeon and a nurse during an operation, or a pilot and co-pilot). Once the task or context ends, both individuals return to their baseline “Individual Agency.” The morphing leaves no structural mark to the self.

Type II: Static (Pathological) Diamorphic Agency. A rigid and coercive morphing of agency enforced by one party’s pathology (e.g., Narcissism) or an exploitative structural hierarchy. Role calcification characterises this type: the dominant agent (Narcissist/Suzerain) requires the subordinate agent (Partner/Vassal) to permanently inhabit a “diminished” shape to sustain the dominant agent’s structure. The subordinate agent eventually loses access to their original agency shape requiring the construction of rigid agency schemas in the serve-response cycle which simulate an idealised ‘false-self’, which they then reinforce in responses from others, perpetuating the pathology.