The Origin Puzzle

The Narcissus myth offers imagery but not explanation. The damage narcissism causes is real and ongoing. Fractured relations, broken families, the erosion of trust that keeps our societies whole.

Consider two individuals who walked into the consulting room within weeks of each other. Marcus, forty-three, arrived in a bespoke suit, radiating the confidence of someone accustomed to deference. A short blonde man with appropriate middle-age spread, and thin arms, he had the fidgety edge characteristic of the New English middle class. A successful property developer, Marcus sought therapy only because his third wife (Emelda) had threatened divorce unless he addressed what she called his ‘impossible ego.’ Marcus quickly described an idyllic childhood: upper-middle-class mansion home, devoted saintly stay-at-home mother, hugely successful father who coached his football team, the best private school education, and of course summer holidays abroad. ‘I had every advantage, nothing was lacking,’ he told me. “My parents adored me. I was a golden child: literally, mother called me that.” Yet beneath the surface, Marcus was an ugly portrait of grandiose narcissism: contempt for those he deemed inferior, explosive rage when challenged, discarded relationships stretching back decades.

Maria, thirty-eight, arrived with absolutely none of Marcus’s apparent confidence. A social worker specialising in child protection, she apologised twice, fussing before sitting down. Her childhood read like a case study in adverse experiences: alcoholic father who left when she was four, mother’s subsequent depression, periods in foster care, sexual abuse by a stepfather, poverty, instability, violence. By any predictive model, Maria should have developed significant psychopathology. Yet here she was: genuine empathy, a stable fifteen-year marriage, two well-adjusted children. ‘I know what damage looks like,’ she said. “I’ve spent my career making sure other children don’t know what I had to.”

Marcus and Maria embody the origin puzzle. If bad parenting causes narcissism, why did Marcus, raised with every apparent advantage, develop the disorder while Maria, exposed to virtually every childhood risk factor, did not? The simple formula ‘traumatic childhood equals narcissistic adult’ cannot account for the outcomes we see every day. Something is clearly missing.

The obvious place to look is in nature via nurture, the complex interplay between inherited temperament, neurobiological development, environmental input, and most important of all—the child’s subjective experience of all three. Kids are not machines. The mechanics of psychology apply to approaches, never the person.

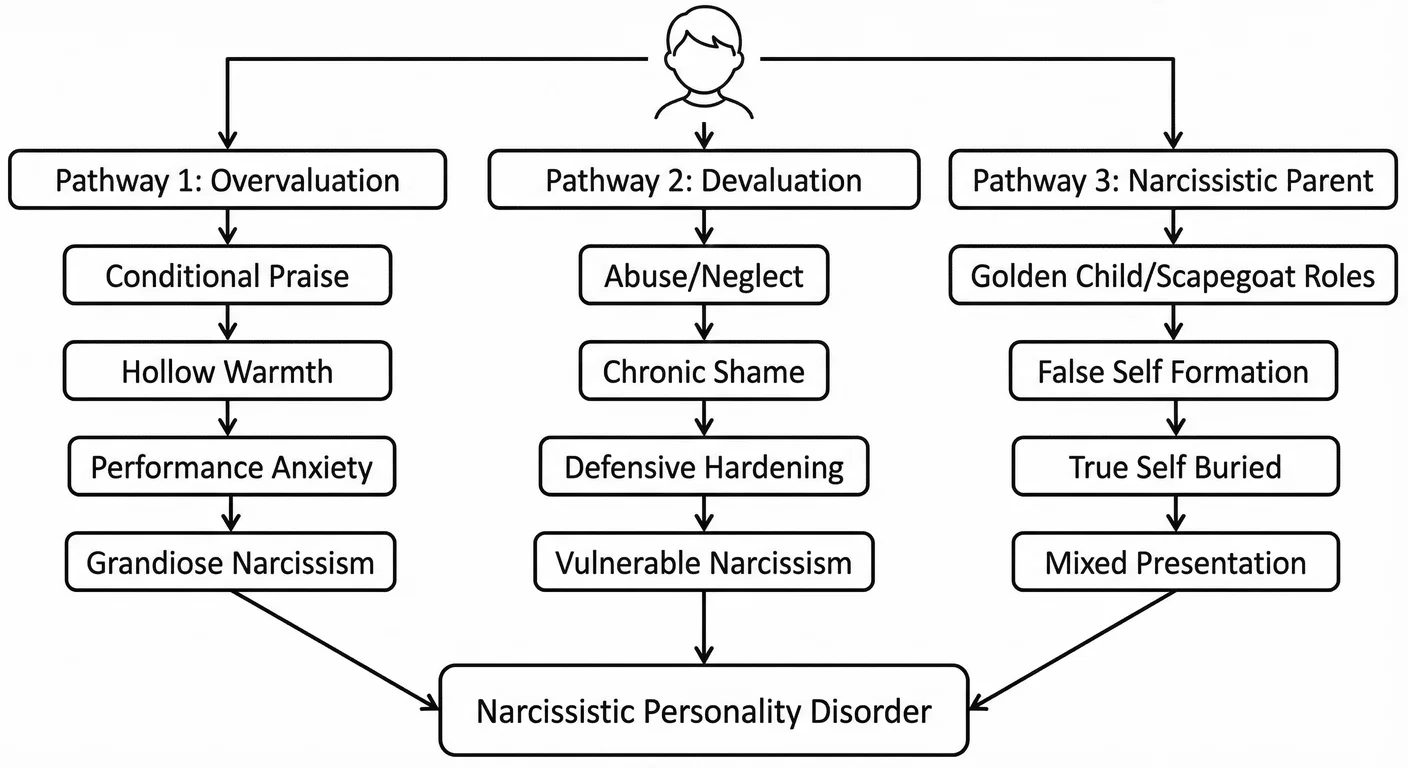

The pathways to narcissism are probabilistic. The principle of equifinality—multiple developmental routes leading to the same outcome—means we cannot identify a single ‘cause’ of narcissism. The narcissistic defence itself primarily obscures understanding of narcissism’s origins. The grandiose False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. functions as a maze, through indirection, and so effectively conceals the developmental wound it protects that even the narcissist forgets the maze was built in response to initial injury. Marcus genuinely believes his childhood was perfect; only careful clinical exploration revealed the conditional nature of his parents’ ‘adoration,’ their investment in his achievements rather than his authentic self, the terror of inadequacy that his grandiosity fought against.

The narcissistic maze stands upon biological and genetic foundations that create fertile ground for the disorder without determining destiny.

The Biological Foundation

The Heritable Component: ‘Is It in the Blood?’

Is narcissism genetic? Yes. What people inherit however is not the disorder itself but a disposition: a collection of genetically based temperamental vulnerabilities which, under the wrong environmental conditions, can crystallise into pathological narcissism . Coal and diamonds both inherit carbon. Their histories ultimately determine their final roles and value to society. This answer frustrates those survivors and victims seeking explanations. Nevertheless, decades of behavioural genetics research confirm that narcissism, like most personality pathology, emerges from the complex interplay of heritable traits and environmental factors. Understanding what exactly is inherited helps demystify why narcissism runs in families yet does not follow neat Mendelian patterns.

Since the rediscovery of Mendel’s work on heritable traits in the peas of his garden in the early twentieth century, researchers have asked whether personality traits are inborn or come from nurture. The answer, consistently, is both. Twin studies, comparing identical twins (who share 100 percent of their genes) with fraternal twins (who share 50 percent)—provide the gold standard for estimating heritability. If identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins on a trait, genetic factors must be involved. Across thousands of studies spanning decades, general personality traits show heritability estimates of 40-60 percent 143 . The remaining variance comes from non-shared environment (experiences unique to each individual) and measurement error. Surprisingly, shared environment, the family environment siblings experience together, typically accounts for near-zero variance in personality by adulthood. This counterintuitive finding, replicated hundreds of times, suggests that whatever shapes personality operates through individual experience rather than family-wide factors.

Narcissistic traits fall squarely within this 40-60 percent range, but the story becomes more interesting when we dissect narcissism into components. A large-scale twin study in 2014 766 examined the genetic architecture of narcissistic personality using over 300 twin pairs. They distinguished between two major dimensions: intrapersonal grandiosity (feelings of superiority and grandiose fantasies) and interpersonal entitlement (exploitativeness and expectation of special treatment). The findings revealed major differences. Intrapersonal grandiosity showed heritability of approximately 24 percent, meaning genetic factors account for roughly a quarter of individual differences in grandiose self-perception. Interpersonal entitlement, however, showed substantially higher heritability at 35 percent.

The interpersonal dimension (how narcissists treat others, their sense of entitlement and expectation of special treatment) appears more genetically influenced. The intrapersonal dimension (the grandiose beliefs, the inflated self-perception) shows stronger environmental influence. One interpretation (from the psychodynamic school of thinking) is that the temperamental traits that make someone prone to exploiting others, feeling entitled, or lacking empathy have stronger biological foundations. The specific content of grandiosity, believing oneself brilliant, beautiful, destined for greatness—gets ‘built’ more through environmental experiences that reward and reinforce these beliefs. This makes early correction even more important in preventing narcissistic traits from growing.

Even more revealing, Luo’s study 766 found that the genetic factors influencing intrapersonal grandiosity and interpersonal entitlement were 92-93 percent independent of each other. This near-complete genetic independence suggests these dimensions represent different heritable vulnerabilities. A person might inherit strong predisposition towards entitlement and interpersonal coldness but not towards grandiose self-perception, or vice versa.

The full narcissistic syndrome, high on both dimensions, must require inheriting both sets of vulnerabilities or, more commonly, inheriting one vulnerability and encountering environments that build the other dimension. This helps explain the heterogeneity within Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) A mental health condition characterised by an inflated sense of self-importance, need for excessive admiration, and lack of empathy for others. : different individuals arrive at similar diagnoses through different pathways. It also provides a way to interrupt the progression of the disorder into maturity.

What exactly is being inherited? The answer is not ‘narcissism genes’ but rather temperamental traits that increase vulnerability to developing narcissistic defences under specific environmental conditions. These include high emotional reactivity and shame-proneness, often expressed in behaviour as reduced affective empathy. The growing child doesn’t care how others feel, or if they have hurt others by stealing from them or destroying what they build. While such traits are continuously distributed in the population; narcissism-vulnerable individuals cluster at the extreme ends.

Consider two infants, Gemma and Oliver, both born into ‘good enough’ middle-class families with reasonably attuned parents. Gemma, from birth, is calm and easily soothed. When her mother is briefly unavailable, Gemma fusses mildly but recovers quickly when mother returns. Oliver, by contrast, is what paediatricians call a ‘difficult baby’—highly reactive and slow to adapt. When mother steps away briefly, Oliver’s distress escalates rapidly to screaming panic. He is harder to soothe and more easily frustrated. Neither set of parents has done anything wrong, yet Oliver’s temperament generates a vastly different interactive environment, and therefore subjective experience. His parents, exhausted and frustrated, may become less attuned or overly accommodating to avoid meltdowns. This is gene-environment correlation, the child’s genetic endowment reshapes the environment they experience — involuntarily.

The ‘confidence paradox’ confuses people about genetics. Narcissists present as supremely confident, yet we are claiming they inherit vulnerabilities. Are not shame-proneness and reactivity signs of weakness? This apparent contradiction evaporates when we remember the grandiose false self as defensive construction. It is the hardened scar over the wound of self. The inherited vulnerability is not confidence but intense shame-proneness and reactive sensitivity to rejection. The grandiosity develops later as psychological armour copied from others and used to shield against the triggers of these painful temperamental traits. The façade obscures the inherited fragility it defends against.

The role of non-shared environment also consistently surprises people. Shared environment—factors siblings experience similarly (family socioeconomic status, neighbourhood, parental divorce)—shows near-zero influence on personality by adulthood. Two brothers may look similar, have grown up in the same home, but are nothing alike. Experiences unique to each child, however, accounts for 35-45 percent of variance in narcissistic traits. What counts? The sibling who inherits difficult temperament while the other does not; the child who experiences parental overvaluation while the sibling is neglected; the daughter parentified into emotional caretaker while the son is babied; the son who is the target of the father’s rage while the daughter is protected. Within every family, children inhabit completely different psychological worlds. We are not machines, and are never merely statistics.

Nathan and Daniel, brothers raised by the same narcissistic father, illustrate this point. Both experienced their father’s grandiosity and criticism, yet Nathan developed narcissistic personality disorder while Daniel, though anxious and approval-seeking, remained empathic and self-aware. The difference? Nathan, the eldest, was the ‘ Golden Child Golden Child The child in a narcissistic family system who is idealised, favoured, and treated as an extension of the narcissistic parent's ego. ’, conditionally overvalued when he achieved, parentified as father’s emotional confidante. Daniel, younger by five years, was largely ignored: painful, certainly, but also protected from the systematic corruption of self Nathan underwent. Same family, same father, radically different psychological outcomes.

The finding does not mean families do not matter—they matter enormously. What matters is how parents treat each child individually—particular parent-child interactions make all the difference. The relevant question is not ‘What was your family like?’ but ‘How did your parents specifically treat you, and how did that interact with your temperament?’ This shifts the focus from family honour and demographic red herrings to particular parent-child interactions. It does not matter how rich, poor, educated, religious, or smart one’s parents are—what matters is whether those interactions were genuinely loving.

We have been down a few blind alleys to get to this stage of understanding, though. From the 1950s through the 1980s, psychoanalytic theory dominated mental health with its assumption that personality pathology resulted primarily from early parenting failures. Mothers were blamed for nearly every disorder—schizophrenic mothers, refrigerator mothers. The possibility that some children might be born with difficult temperaments that stressed even competent parents was ideologically unthinkable. This ‘blame the mother’ thinking heaped guilt on struggling parents while obscuring the reality that all of us arrive with different neurobiological endowments requiring specific parenting approaches. Only with the behavioural genetics revolution of the 1980s and the following computational burst in the 1990s did the field reluctantly acknowledge that temperament matters.

Of course this put even more responsibility onto parents, just a different kind. The 24-35 percent heritability means 65-76 percent of narcissistic variance comes from environment and gene-environment interplay. Alright, temperament creates vulnerability, we now know: but parenting and environment determines outcome.

A shame-prone, reactive child with ‘good enough’ parents who provide patient attunement and emotional coaching may develop healthy self-esteem—grounded self-regard and appropriate concern for others. That same child with overvaluing parents who exploit the child’s sensitivity may develop pathological grandiosity. The same child with devaluing, abusive parents may develop Malignant Narcissism Malignant Narcissism The most severe form of narcissism, combining NPD traits with antisocial behaviour, sadism, and paranoia—representing a dangerous intersection of personality pathology. . Biology is not destiny; biology creates the soft spot while the parents exploiting that spot to play out their needs decides whether adaptive or maladaptive defences develop. Parents act as sculptors, shaping inherited raw material into healthy or pathological forms.

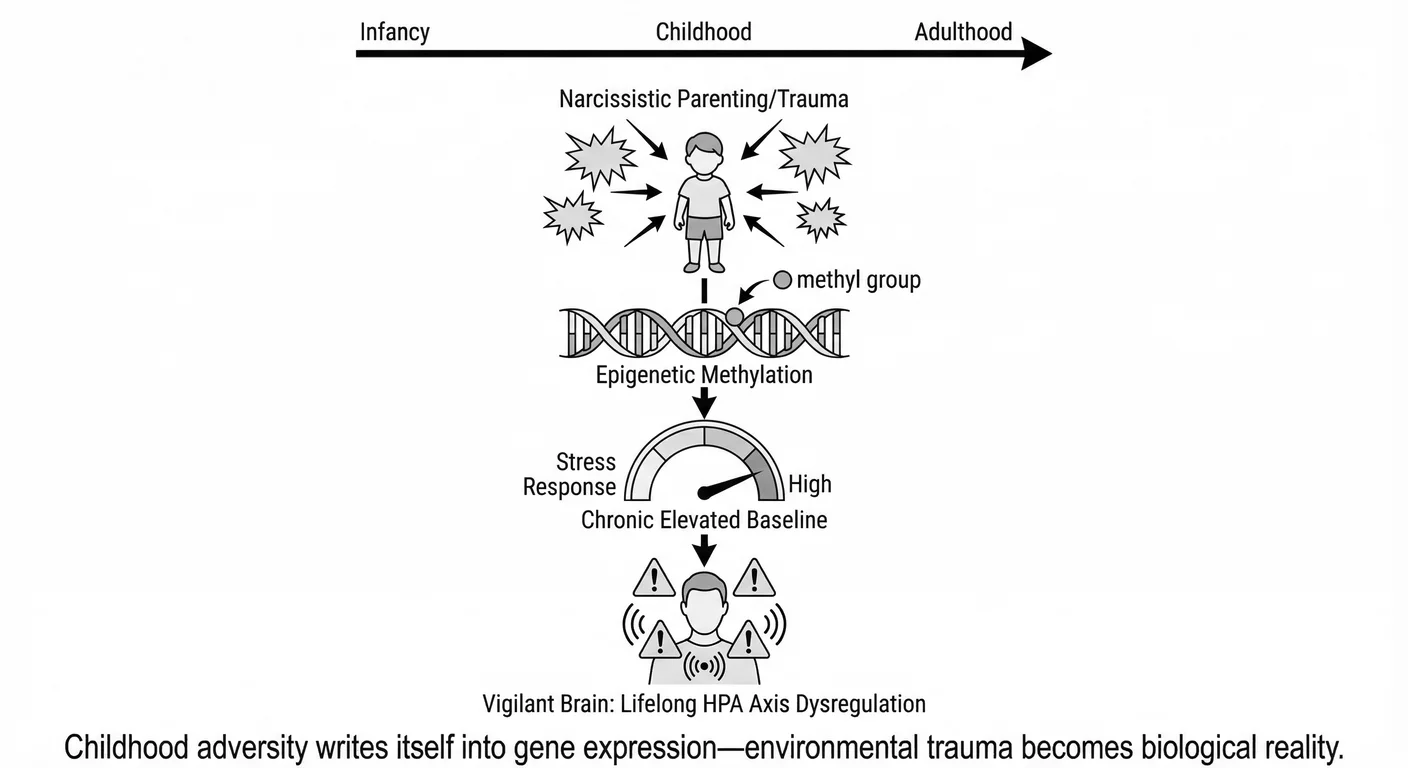

The neural terrain of these heritable vulnerabilities become clear when we look at specific brain differences in narcissistic individuals. We can literally see neural problems that make the temperamental person run differently. Shame-proneness and low empathy—these are not imaginary but reflect visible differences in physical brain structure and function. The actions of parents damage and break their child’s brain in very specific ways. This is hard truth of why narcissism is so difficult to change through willpower alone.

The Neurobiology of Narcissistic Vulnerability

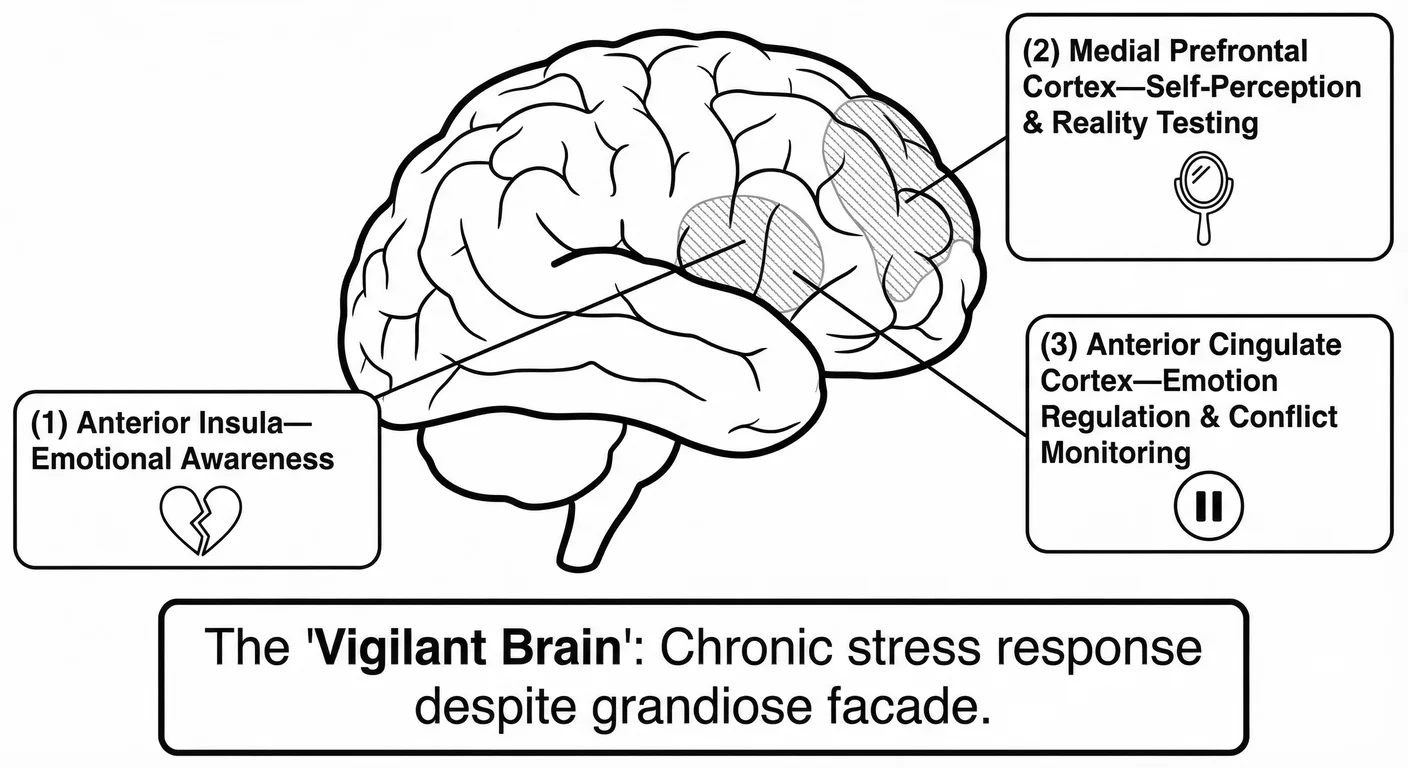

Three regions of the brain show consistent abnormalities in NPD.

The anterior insula, which translates bodily states into felt emotions and enables empathic resonance, shows reduced grey matter volume and blunted activation during empathy tasks 1104 . The narcissist can read people acutely, and know why they’re suffocating, or drowning, while remaining unmoved by their suffering.

The medial prefrontal cortex, responsible for self-referential processing and accurate self-perception, shows similar deficits 910 .

The anterior cingulate cortex, which monitors conflict and regulates emotional responses, cannot create the pause between stimulus and response that enables measured reactions rather than defensive explosions.

Together, these deficits create what researchers call the ‘vigilant brain’ phenomenon: despite feigning supreme confidence, narcissists show elevated physiological stress responses to ego threats and chronic baseline hyper-arousal. They are terrified. The grandiose façade masks constant threat detection and regulatory systems struggling to contain primitive emotions.

These brain differences are not entirely inborn. Failed parenting makes the situation far worse. Early relational trauma can cause or exacerbate neural deficits through neuroplasticity, creating a two-way process: genes influence brain development, which shapes parent-child interactions, which further shape the developing brain. The vulnerable child and the failing environment concentrate the narcissist creation process together.

The Developmental Crucible (The ‘Nurture’)

Two psychoanalytic frameworks influence our understanding of narcissism’s developmental origins. Heinz Kohut saw it as developmental arrest: a self frozen in infantile grandiosity because essential needs went unmet. Otto Kernberg, on the other hand, saw pathological defence: an actively constructed maze protecting against cold, aggressive parenting. Both were right—they described different aspects of the same disorder.

The Two Developmental Models

Kohut’s ‘Tragic Man.’ Kohut argued that healthy development requires caregivers who function as selfobject s—providing mirroring (the child is seen and affirmed) and idealisation (the child can merge with a powerful, calm presence) 674 676 . When these needs are chronically unmet—through emotional unavailability or subtle use of the child to regulate the parent’s self-esteem—the grandiose self never transforms into healthy self-regard. The result: desperate need for external validation and fragile self-esteem that collapses into shame when admiration is withdrawn.

Kernberg’s ‘Angry Man.’ Kernberg emphasised that some children experience caregivers as actively hostile—responding to dependency with coldness or rage 649 650 . The child cannot integrate the reality that ‘the parent I depend on hates me, hurts me’ so creates a ‘pathological grandiose self’: a fusion of real self, ideal self, and ideal object that proclaims ‘I need no one; I am complete unto myself.’ This grandiosity is fuelled by aggression redirected from the dangerous parent—turned against the vulnerable self (‘weakness is contemptible’) or projected onto others (‘they hate me’). The result: cold empathy and contemptuous exploitation.

Synthesis. Both presentations exist, often in the same person. The ‘tragic man’ can harden into contemptuous rage when vulnerability feels too dangerous; the ‘angry man’ harbours the terrified child underneath. Modern neuro-imaging validates both models: the ‘vigilant brain’ in chronic defensive alert (Kernberg’s defence) coexists with structural deficits in empathy circuitry (Kohut’s arrested development) 1104 910 . Both pathways—emotional neglect (Kohut) versus active hostility (Kernberg)—can produce similar outcomes, especially when interacting with the temperamental vulnerabilities discussed earlier.

Pathway 1: The ‘Special’ Child (Parental Overvaluation)

This is perhaps the most misunderstood pathway to narcissism because, from the outside, it resembles loving, attentive parenting. Affluent families, educated parents, children enrolled in elite schools—the external markers suggest success and investment. How could this environment produce narcissistic pathology? The answer lies in a subtle but grotesque dynamic first systematically articulated by 869 Millon’s biopsychosocial theory: the child is loved for social value, for what they represent and accomplish. They are treated as special, exceptional, superior to others, but this treatment makes them property; it also signals that ordinariness is unacceptable, that the child’s relaxed normal self is insufficient, that love is conditional on maintaining an inflated image the parents need the child to embody. Millon proposed that narcissism develops when parents provide ‘uncontrolled praise and compliments,’ combined with excessive permissiveness, teaching the child they are better than others and qualified for special treatment regardless of effort or performance. This social learning theory perspective has been systematically validated in subsequent empirical research 173 .

The key empirical study documenting this pathway came from 173 Brummelman in 2015, who conducted a long-term investigation tracking children and their parents over 18 months. The research design was elegant: parents completed questionnaires assessing two distinct constructs. Parental overvaluation was measured through items like ‘My child is more special than other children’ and ‘My child deserves something extra in life.’ Parental warmth, by contrast, was assessed through items like ‘I let my child know I love him/her’ and ‘I express affection to my child.’ These might seem like similar constructs (do not parents who think their child is special also love them warmly?) but the data revealed they were statistically independent and predicted radically different outcomes.

Parental overvaluation predicted increases in narcissistic traits over the 18-month period. Children whose parents saw them as more special than others, as deserving special treatment, developed higher scores on narcissism measures assessing grandiosity and entitlement. The effect was specific: overvaluation predicted narcissism without predicting self-esteem. Parental warmth, conversely, predicted increases in self-esteem (children felt good about themselves, secure in their worth) but did not predict narcissism. Warmth without overvaluation produced healthy self-regard. Overvaluation without warmth produced narcissistic grandiosity.

The most damaging pattern, though rarely measured explicitly in research, is the combination of overvaluation with hollow warmth, praise disconnected from genuine emotional attunement. The child receives the message ‘You are special’ but not the deeper message ‘You, your actual inner experience, your authentic feelings, are precious to me.’

Why does overvaluation create narcissism rather than healthy confidence? Parental warmth says: “You are lovable as you are. Your existence brings me joy. I delight in you.” This is Kohut’s mirroring, the parent’s eyes lighting up not because the child performed but because the child exists. The child realises this and so internalises: “I am inherently valuable. I belong. I am enough.” Parental overvaluation in contrast says: “You are superior to others. You deserve special treatment. Ordinary standards don’t apply to you.” This communicates several complex lessons. First, your value is comparative—you matter because you are better. This means if you are not better, you do not matter. Secondly, you are not like other people—you exist in a separate category, they are not like you for you to be important, and you cannot be like them for you to be important, thus preventing empathy development. Third, I need you to be special—making the child responsible for regulating the parent’s self-esteem, and thereby parentifying them. These are overwhelming realities for a child’s system to try to integrate. Whichever way they turn, who they actually are isn’t enough; their real self finds no connection. The only way to keep going is by presenting a false self to cope.

Otway in 2006 941 tested competing psychoanalytic predictions about narcissism’s developmental origins in a sample of 120 UK adults using an approach called structural equation modelling. The findings uncovered a suppression relationship: both overt and covert narcissism were predicted by both recollections of parental coldness and recollections of excessive parental admiration, and decisively, the effects of each were stronger when modelled together than separately. The most harmful combination is parental overvaluation with parental coldness. We call that the ‘hollow praise’ phenomenon. The child receives inflated praise for performance or appearance while experiencing emotional coldness when attempting to express authentic feelings or needs. The parent teaches the child that their normal self deserves no love. This aligns with 1309 Webb’s formulation of Childhood Emotional Neglect (CEN), which is defined as parents’ failure to respond adequately to a child’s emotional needs. In the overvaluation pathway, parents respond enthusiastically to the child’s achievements but remain indifferent when the child expresses vulnerability or ordinary needs for comfort. The message is devastating: ‘You are special’ (overvaluation) combined with ‘Your inner emotional self is not worth my attention’ (CEN). Over time the child learns that only the grandiose false self receives any validation; the authentic, vulnerable true self is ignored or implicitly rejected.

Children are very finely attuned to what parents truly value. When parents overvalue, children learn that the grandiose self—the special, superior, exceptional self—is actually what receives parental attention and approval. The ordinary self: the child who feels scared or simply wants to play rather than achieve, receives indifference or rejection. The child cannot afford to lose parental approval, so the authentic self goes underground. They can’t let it show, from now on they must role play. The grandiose false self evolves through a series of learned reactions into the only identity the child dares present. From the outside, the child appears pampered and showered with attention, but is emotionally starved. The praise never touches the real child, only the performance. The child learns to perfect the performance while the inner self remains unknown and eventually inaccessible even to the child themselves as they literally forget what it was like to be seen, or how to ask to be seen.

The cruel fact of overvaluation is what looks like love is exploitation. Parents will convincingly say they are supporting their child and investing in their future. They seem horrified to hear they are causing psychological damage. Yet the child is not a separate person with their own independent desires and developmental needs—they are an extension of parental narcissistic needs, a vehicle for parental ambitions. When confronted with this they say it is about culture, or religion, or identity and how could it be any other way?

Such children also often say, ‘They gave me everything.’ In material terms, this may be true. It’s irrelevant. In emotional terms, they received nothing they actually needed: acceptance of their authentic self, attunement to their feelings, even simple permission to be ordinary and receive genuine unconditional love.

Overvaluation produces narcissism via neurobiological deficits. Narcissists show reduced grey matter in the anterior insula, the brain region supporting emotional empathy. So, why would overvaluing parenting impair empathy development? Because empathy requires experiencing oneself as similar to others: ‘What I feel, they feel; what hurts me, hurts them.’ Overvaluation teaches that this is futile: ‘You are different from others, special, superior.’ As a consequence, the brain region that should come into play—the anterior insula—atrophies through lack of use. Worse still, the child never grows the associated neural circuitry for emotional resonance with ‘ordinary’ people because the child is trained to see themselves as categorically different.

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the brain region responsible for executive functioning, suffers drops in self-awareness that similarly make sense. When a child’s authentic feelings are consistently ignored in favour of the grandiose performance, the neural connections between internal states and conscious awareness never adequately develop. The child becomes skilled at reactively performing the false self while losing the opportunity to grow a true self.

The parental motivations behind overvaluation vary but share a common thread: the parent is using the child to regulate their own self-esteem. Some parents are themselves narcissistic, requiring a special child to reflect their specialness. These parents experience the child’s ordinariness as a flavour of narcissistic injury: “My child got a B? That makes me look bad.” Other parents, paradoxically, have low self-esteem and live vicariously through the child’s achievements. These parents might have failed to achieve their own ambitions: the parent who dreamed of musical stardom now pushes their child into grueling practice schedules. Still other parents come from marginalised groups and view the child as the family’s hope for social mobility or vindication: immigrant parents who sacrificed everything for the child to succeed, working-class parents determined their child will transcend their circumstances, minority parents who see the child as a symbol of group achievement. The motivations differ, but the impact on the child is the same: you exist to fulfil my needs, not to develop your own authentic self. You are property.

This pathway is most easily noticeable in families with resources—upper-middle-class and wealthy families who can afford elite schools, private tutors, travel sports leagues, music conservatories. However, we see variations on it in all levels of society. From the outside, these families look successful, functional, even healthy. The parents are educated, articulate, superficially warm. They attend school functions, volunteer for fundraisers, network with other parents. The child appears accomplished, poised, confident. Neighbours and teachers see an enviable family with a child making progress. Even mental health professionals can be deceived initially. Only those close to the family, or the adult child years later in therapy, feel the discordant undertones, and discover the reality. The child’s inner experience is one of chronic performance anxiety, fear of failure, inability to relax, compulsive achievement-seeking, and pervasive emptiness. The grandiose self is there to maintain the only identity that receives parental recognition.

Adult children of overvaluing parents often achieve external success (they have the skills, work ethic, and competitive drive the parents instilled) but experience no satisfaction. At all. Every achievement feels hollow, already insufficient. They must chase the next accomplishment compulsively, driven not by genuine ambition but by terror of ordinariness, the entropy of all things consumes them. Relationships fail because they can only relate to others as audiences (admirers to supply narcissistic validation) or competitors (threats to be destroyed). Authentic intimacy requires vulnerability, the capacity to be seen as ordinary, flawed, human, precisely what the overvalued child learned was unacceptable. The false self that shielded them in childhood becomes their prison in adulthood, and dismantling it requires grieving the childhood they never had: one where they were loved not for being special but for being themselves. That’s too painful to bear. Too painful to even see, or acknowledge.

Pathway 2: The ‘Devalued’ Child (Abuse & Neglect)

If the overvaluation pathway resembles love gone wrong, the devaluation pathway is pure despair. This is the territory of overt abuse and neglect that most people associate with childhood trauma. Yet even here, this pathway produces the rigidly defended grandiosity of narcissism. How does extreme devaluation, being treated as worthless and contemptible, create a personality proclaiming superiority and specialness?

The empirical evidence documenting this pathway has accumulated systematically over the past two decades. The key study came from Johnson in 2001 611 , who conducted a community-based longitudinal investigation following 793 families from two New York State counties across four time points spanning seventeen years (1975–1993). The study design was prospective—families were recruited when offspring were aged 5, then followed through adolescence (ages 14 and 16) into early adulthood (age 22), with comprehensive psychiatric and psychosocial interviews at each touchpoint in the study. This longitudinal design allowed researchers to establish temporal precedence: childhood experiences preceded personality pathology, not vice versa. The findings were shocking and dramatic, and have been replicated multiple times.

Children who experienced maternal verbal abuse during childhood were more than three times as likely to develop narcissistic personality disorder during adolescence or early adulthood. This association remained statistically significant even after controlling for potentially confounding variables including offspring temperament, childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, physical punishment, parental education, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. This signal shone through all those other factors. The specificity of verbal abuse as a risk factor, independent of other forms of maltreatment, suggests that contemptuous, shaming communication patterns were particularly pathogenic for narcissistic development. What those mothers said to their children deformed their lives.

The relationship between childhood maltreatment and narcissism has been synthesised in a comprehensive meta-analysis by Gao in 2024 441 . That study analysed 15 studies encompassing 9,141 participants to quantify the relationship between child maltreatment and pathological narcissism.

Child maltreatment positively predicted both vulnerable and grandiose narcissism, though the effect for vulnerable narcissism was more than twice as large.

This association (maltreatment more strongly predicting vulnerable than grandiose narcissism) provides confirmation of the clinical observation that abuse and neglect primarily produce the anxious, shame-prone, hypersensitive presentation rather than the overtly entitled and exhibitionistic grandiosity associated with parental overvaluation.

Felitti’s 381 Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Potentially traumatic events occurring before age 18—including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction—with documented long-term effects on health and wellbeing. (ACEs) framework illuminates this developmental pathway. The original ACE Study, conducted with over 17,000 adults at a Kaiser Permanente health maintenance organisation, documented ten categories of childhood adversity:

-

psychological abuse,

-

physical abuse,

-

sexual abuse,

-

emotional neglect,

-

physical neglect,

-

witnessing domestic violence against mother,

-

household substance abuse,

-

household mental illness,

-

parental separation or divorce,

-

and incarcerated household member.

The finding was clear—as ACEs increased, so did the risk for numerous physical and mental health problems in adulthood, including depression, substance abuse, and personality pathology.

Later NPD research confirms ACEs as the primary situational risk factor. Adults who went through four or more ACEs, compared to those who experienced none, showed elevated narcissistic traits even after controlling for current socioeconomic status—showing that the effects of early adversity persist across the lifespan, no matter what happens later. These children carry that weight forever.

This pathway primarily produces vulnerable narcissism—also termed covert or hypersensitive narcissism—rather than the grandiose presentation often associated with overvaluation. 867 Miller in 2018, using structural equation modelling and item-response theory, showed that vulnerable narcissism is primarily marked by neuroticism. It is characterised by shame-proneness and emotional lability—emotions easily aroused and shifted by criticism—combined with antagonistic rather than agreeable interpersonal functioning. They will only rejoin the party of humanity if no one makes fun of them.

Specifically, neuroticism—fear of the future—accounted for nearly two-thirds of the variance in vulnerable narcissism, while antagonism explained an additional fifth. The observable markers of vulnerable narcissism and neuroticism were nearly identical in the data, hinting strongly that these constructs share almost the same operational laws.

Disagreeableness-related traits—distrustfulness and interpersonal exploitation—largely explained the remaining variance in vulnerable narcissism.

These children grow up to experience chronic feelings of inadequacy and unworthiness beneath a defensive veneer of superiority. The grandiosity is brittle and desperate; it is skin-tight compensation against overwhelming feelings of worthlessness caused by parental devaluation and abuse. This does fit with Kernberg’s formulation better than Kohut’s: the grandiose self is active defence, not developmental arrest, though what it defends against is severe trauma, not just empathic failure.

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying this pathway connect to Schore’s 1096 work on Affect Regulation Affect Regulation The ability to manage and respond to emotional experiences in healthy ways—often impaired in both narcissists and their victims. and early brain development. Schore showed that right hemisphere development, which matures earlier than the left and governs emotional processing and stress response, critically depends on attuned caregiver-infant interactions during the first three years of life. When parents reliably respond to infant distress with soothing and validation, the infant’s developing orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex build the capacity to modulate and handle overwhelming emotions. They internalise the comfort, and learn to do it themselves. The caregiver’s regulated nervous system literally helps organise the infant’s dysregulated nervous system through what Schore terms ‘psychobiological attunement.’ Love is contagious, in the best sense.

But when caregivers are abusive or neglectful, chronically unavailable, this regulatory scaffolding never forms. The child’s nervous system remains in chronic dysregulation, hypervigilant to threat, unable to self-soothe. This early relational trauma becomes encoded in neural architecture, creating the structural and functional brain differences observed in adult narcissists 1099 .

And yet, most of the damage is down to the role of shame as both antecedent and consequence. Contemporary psychodynamic research by Pincus 992 and Roche 1043 has shown that narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability represent oscillating states rather than discrete subtypes, as first thought. Their integrative model, validated through intensive longitudinal assessment and interpersonal process analysis, shows that shame is the affective state that triggers defensive grandiosity in vulnerable narcissists . When people high in vulnerable narcissism experience shame-inducing situations: criticism, perceived rejection, social comparison revealing inadequacy—they cannot tolerate the affect as healthy people with secure self-esteem would. Shame triggers what Pincus 992 terms ‘narcissistic grandiosity states’—temporary defensive surges in exhibitionistic behaviour, arrogant self-promotion, and contemptuous devaluation of others. These grandiose states are attempts to regulate the unbearable shame affect, creating psychological distance from feelings of worthlessness and inferiority. Crucially, shame is strongly associated with vulnerable narcissism but shows a negative relationship with Grandiose Narcissism Grandiose Narcissism The classic presentation of narcissism characterised by overt arrogance, attention-seeking, dominance, and open displays of superiority and entitlement. , though this reflects defensive suppression rather than genuine absence of shame. Physiological and implicit measures reveal that individuals high in grandiose narcissism show elevated shame responses at unconscious levels despite consciously denying shame experiences—the body knows what the mind denies.

The actual types of ACEs that characterise this pathway include emotional abuse—being told you are worthless, that you should never have been born, that everything wrong in the family is your fault.

This differs from the emotional neglect in the overvaluation pathway. Neglect is absence: nobody responds to your feelings. Abuse is presence: someone responds to your feelings with contempt or rage.

A child expressing sadness might be told “Stop your crying or I’ll give you something to cry about.” A child expressing fear might be ridiculed: “Don’t be such a coward. You’re weak, just like your father.” The message is not merely that feelings are unimportant but that having feelings makes you contemptible, that vulnerability equals worthlessness. This systematic shaming of the authentic self, what Johnson 611 identified as the key element in verbal abuse, instils chronic shame-proneness that evolves into the affective foundation for vulnerable narcissism.

Physical abuse (being hit, slapped, beaten as punishment or displaced rage) teaches the child they are an object, not a person; that their body can be violated with impunity; that power determines worth.

Sexual abuse inflicts the most devastating message: you exist for others’ gratification; your boundaries mean nothing; you are fundamentally damaged goods.

Physical neglect—inadequate food, shelter, medical care, supervision—communicates you do not matter enough to keep alive. The child internalises: “I am unworthy of basic care. My survival is negotiable.”

Household problems compound direct abuse, and the tragedy is they frequently go together. Witnessing domestic violence teaches that relationships involve dominance and violence. The child learns, falsely, that love and fear are joined at the hip, that intimacy means danger.

Growing up with substance-abusing parents means chronic unpredictability: will parent be available or incapacitated? Loving or rageful? The child’s nervous system never gets to rest, constantly scanning for signs of danger.

Parental mental illness, particularly when the child becomes parentified, forced into the caregiver role for the mentally ill parent, inverts the natural order: the child must suppress their own needs to manage the parent’s emotional dysregulation. This means the child doesn’t just have to manage their own lives, steer their own emotions, ask for help when they need it, and avoid danger—they have to do that work for their caregivers. Their own needs get pushed down and never properly surface, and so they cannot see or understand themselves past the world of their parents.

Parental incarceration or abandonment inflicts the wound of unworthiness: ‘If I were valuable, they would have stayed.’ Each ACE alone is damaging; in combination, they create what van der Kolk 1272 called complex developmental trauma: chronic, inescapable threat from the people who should provide safety.

So why does this constellation of trauma produce narcissism rather than borderline? Both start with childhood trauma and involve emotional dysregulation. And still, their responses differ. The answer lies in the interaction between genetic temperament and trauma timing and type 950 . Emerging evidence suggests that the full NPD syndrome shows higher heritability (approximately 77% in clinical samples, higher than individual trait estimates) than borderline personality disorder (40–50%), with different underlying genetic vulnerabilities 1230 . While BPD correlates with genetic factors related to emotional dysregulation, NPD appears linked to temperamental antagonism—a predisposition towards interpersonal dominance and callousness rather than emotional lability.

When a child with antagonistic temperament experiences abuse, the reaction is not going to be emotional fragmentation but hardening: “I will never be vulnerable again. I will be invulnerable.” The BPD patient’s core terror is abandonment; but the narcissist’s core terror is worthlessness. BPD coping involves clinging, emotional amplification, desperate attempts to maintain connection even at cost of self-destruction. Narcissistic coping involves withdrawal into grandiose fantasy, emotional shutdown, contemptuous dismissal of need for connection.

The BPD patient says “I am nothing without you; please don’t leave me.”

The narcissist says ‘I need no one; you are nothing.’

Both statements defend against unbearable pain. But we can see they go in different, opposed directions. Moreover, trauma timing appears critical: severe early neglect and abuse in the first three years (during Schore’s critical period for affect regulation development) is more likely to produce narcissistic coping, while trauma during later childhood and adolescence, particularly involving unstable attachment relationships, leans towards borderline pathology. The later difference in approach signals that the child has sensed an inner self with some connection which evaporates when the other person vanishes. This remains an area requiring further empirical investigation, but clinical observation suggests children who develop narcissism often describe early severe neglect followed by expectations to perform or care for parents regardless of the kafkaesque nature of the situation—a combination of abandonment and exploitation rather than the chaotic enmeshment and confusion often reported by borderline patients.

The signature of vulnerable narcissism is that grandiosity is compensation, not a conviction. The person can’t actually believe in their superiority; yet they desperately need to believe it to survive. Any evidence contradicting the grandiose false self-image therefore triggers anxiety spikes, the threatened return of unbearable early feelings of worthlessness and abandonment.

The long-term consequences of this pathway are perhaps the most tragic because the narcissistic defence, initially adaptive, hardens into a self-perpetuating maze, and prison. The child who vowed ‘I will need no one’ evolves into the adult who cannot form authentic relationships nor experience vulnerability—unable to access the very human connection that might repair the original wound.

Every relationship confirms the narcissist’s worldview: people are unreliable, exploitative, disappointing. They never see that their own defensive withdrawal and contempt set up these outcomes. The reaction that shielded the wounded child destroys the adult’s chance for healing. And because the grandiose defence is so rigidly maintained, so well-fitting to their history and worldview that it feels like their true self, the narcissist will not seek help until external consequences become unavoidable—divorce, job loss, or the realisation of complete isolation. By then, often it is too late.

Pathway 3: The Narcissistic Parent (The ‘Dual’ Role)

The first two pathways seem like opposites—one child drowning in praise, the other in contempt. Pathway 3 reveals they often appear together and complement each other in the same family. When the parent is narcissistic, overvaluation and devaluation become tools deployed strategically, sometimes to the same child on the same day.

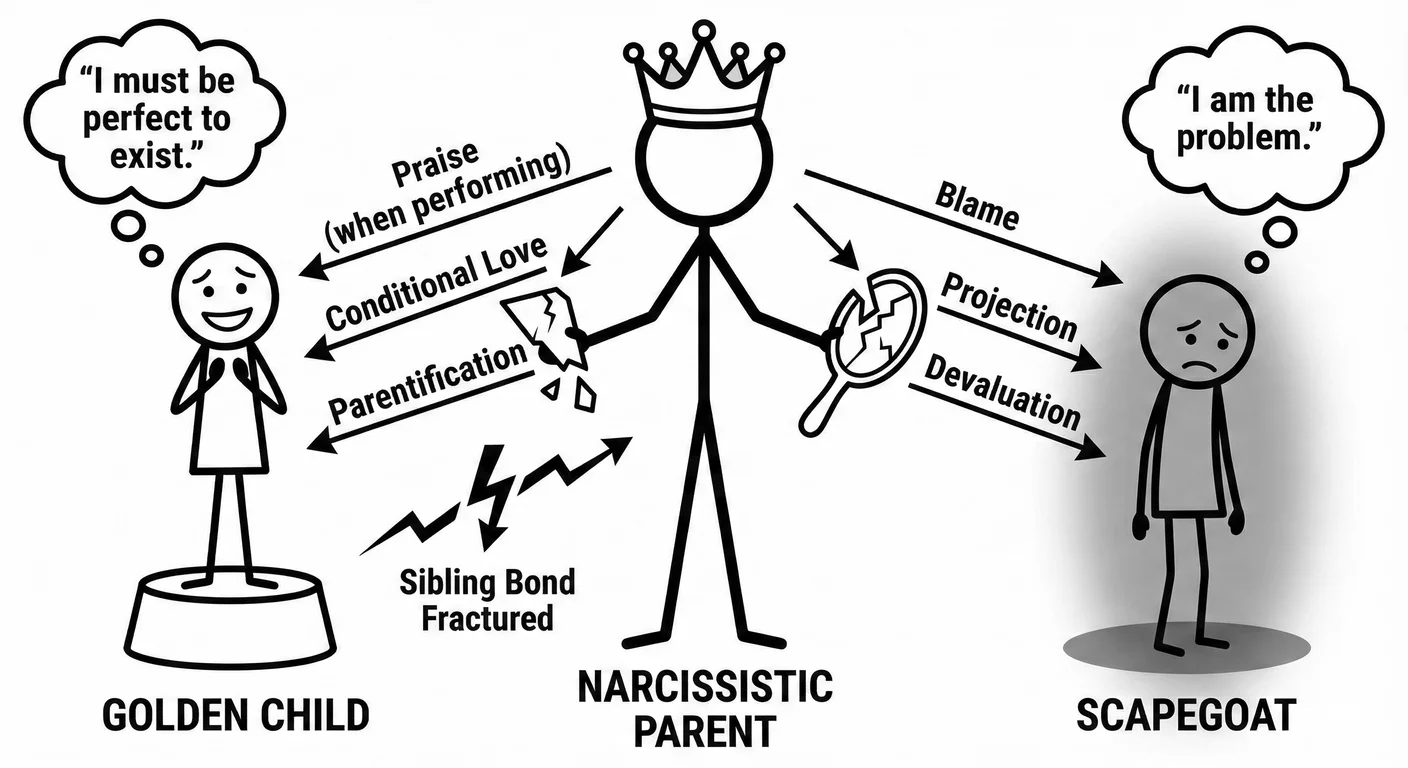

Thomaes 1223 calls this ‘intergenerational transmission’—a banal name for what is a birthright of cruelty and suffering, the parent’s narcissism directly scarring the child’s mind. But that clinical phrase, like all clinical terms, sanitises the brutality. The defining feature is what Winnicott 1333 termed failure of the holding environment : the caregiver’s unwillingness to see their child as a separate person with their own inner life.

In narcissistic families, the child is never more than a commodity. An extension. A prop in the parent’s psychological drama. They provide emotional servicing. The child regulates the parent’s fragile self-esteem—meaning they can’t be an autonomous being with legitimate needs 830 1025 .

The child’s personhood is erased. Not neglected. Erased.

Schore 1099 explained through his research why this failure matters. During the first three years—when the right hemisphere dominates and the circuits for emotional regulation are being built—the child requires what he calls ‘psychobiological attunement.’ The caregiver must respond not just to what the child does but to what the child feels. The narcissistic parent won’t do this; it is work without supply. They cannot wonder what their child is experiencing—that inner life threatens their need to use the child as mirror or prop.

Fonagy 404 calls this Mentalization Mentalization The capacity to understand behavior—in ourselves and others—in terms of underlying mental states like thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions. Narcissists show deficits in this crucial social-emotional skill. —holding another person in mind as a psychological being with their own thoughts and feelings. Narcissistic parents fail here. Not because they lack intelligence. Because genuinely wondering ‘What is my child feeling?’ would require recognising the child as separate from their own needs.

The parent looks at the child and sees only themselves. The Golden Child Golden Child The child in a narcissistic family system who is idealised, favoured, and treated as an extension of the narcissistic parent's ego. reflects their idealised self. The scapegoat carries their equally important disowned shade. Neither is an actual child.

Winnicott’s true self versus false self explains how the child copes. The true self is the spontaneous core—the child’s genuine feelings, their emerging sense of ‘this is me.’ In Good Enough Parent Good Enough Parent A concept from pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott describing parenting that meets the child's needs adequately but not perfectly. The 'good enough' parent provides consistent care while allowing age-appropriate failures that help the child develop independence and resilience. ing, the mother meets the infant’s spontaneous gestures with responsive mirroring. The child learns: ‘My feelings are real. I exist.’

But when the caregiver cannot tolerate spontaneity—when she needs the infant to be something other than what it is—the infant learns survival depends on compliance. A false self must surface: a protective shell presenting what the caregiver needs to see. It must be all that they see. The true self therefore goes into hiding. In narcissistic families, this isn’t occasional. It’s chronic and pervasive. It becomes law. The child learns from infancy that their life, their role, their place, their future depends on performing a role in someone else’s drama. Social theatre on a tightrope, over lava.

The golden child’s inner monologue suddenly seems obvious: ‘If I stop performing, I stop existing.’

The scapegoat’s less so, but still clear: ‘I could cure cancer and she’d ask why I didn’t cure it sooner.’

Assor 53 measured this in the real world through what he called parental conditional regard—affection conditional on meeting parent-imposed standards. Both conditional positive regard (warmth when you succeed) and conditional negative regard (withdrawal when you fail) predicted the same outcomes: resentment towards parents, compulsive task persistence even without motivation, and most critically, self-esteem that rises and crashes based on external validation.

Roth 1063 confirmed the pattern: conditional regard predicts suppression of negative emotions and thereby reduced vitality. This makes some sense—if you’re waiting for permission to feel validated, then you’re not likely to feel that way before or after. The whole shape and texture of your day, your world, changes. Those moments, and people, they become gravity wells, planets or stars, and everything beyond them is just the cold void. The child therefore learns to perform through those voids while feeling nothing. Winnicott’s false self translated into measurement: a constructed persona centred around compliance while the true self—the source of genuine aliveness—shrinks and then dies from disuse.

Vignando 1278 tested this mechanism directly, examining whether scapegoating mediates the link between parental narcissism and child distress. The finding was ugly: scapegoating accounted for significant variance in both anxiety and depression—even beyond the direct effects of having a narcissistic parent. Being the family scapegoat isn’t just subjectively miserable. It’s a concrete, real mechanism through which parental pathology transmits damage to the next generation.

The scapegoated child doesn’t just feel bad. They are being actively hurt, shaped into a more unfeeling, cruel being who will do the same to their children.

Narcissistic family systems run on the machinery of splitting—dividing people into ‘all good’ and ‘all bad’ with no room for complexity. This mechanism is a direct result of the empathy shortfall: proper, fully realised decisions are impossible because the empathy that provides them is missing, so splitting provides a reactionary shortcut. The narcissistic parent projects this onto the family structure almost reflexively: the Golden Child Golden Child The child in a narcissistic family system who is idealised, favoured, and treated as an extension of the narcissistic parent's ego. receives idealisation, the scapegoat receives Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. and devaluation. These aren’t arbitrary assignments. They’re complementary roles in a system that requires both. The contrast between the two highlights the two, and intensifies the perceived power of the parent feeding into their grandiosity.

The golden child gets the apparent warmth, while starving. The scapegoat watches, not even receiving that.

McHale 838 and Jensen 606 documented what happens later in life: favoured siblings have better mental health, fewer behavioural problems, stronger relationships. Disfavoured siblings show elevated anxiety, depression, compromised sibling bonds. The pattern established in childhood directly predicts relationship quality, mental wellbeing, even material support in adulthood. Disfavoured children report higher depression and lower life satisfaction decades after leaving home. They are still carrying the weight.

The golden child’s position isn’t enviable either. With overvaluation they bear additional burdens: parentification and systematic conditional regard. Conditional parenting forces parentification—role inversion where the child assumes responsibility for the parent’s emotional needs. They come to feel directly responsible for the parent’s cruelty, rage, neglect, and abuse. Jones 616 found it specifically predicts both narcissistic and self-defeating personality traits. The mechanism is perverse: the parentified child learns their worth depends on servicing others while developing grandiose compensatory fantasies to manage the rage of having their own needs systematically ignored.

Hooper 570 confirmed this in a 2011 meta-analysis: parentification reliably predicts adult psychopathology, especially, unsurprisingly, in mood and personality disorders. In narcissistic families, it rarely occurs alone—it combines with enmeshment, conditional regard, and pressure to serve as the parent’s ‘trophy.’

Allison, a 34-year-old doctor, entered therapy seemingly out of the blue, guardedly reporting ‘vague dissatisfaction’ despite ‘having everything.’ The clinician, a bearded and wily Hungarian spotted something in this and invited her in for a consultation, insisting it should be in the morning.

Allison was the eldest; a daughter of a mother with prominent narcissistic traits. From early childhood, she was singled out as ‘the special one’—precociously verbal, academically gifted, physically attractive. Her mother paraded these qualities to relatives and neighbours, comparing Allison favourably to other children and to her younger brother Daniel, who evolved, predictably, into the family scapegoat.

But she knew the praise was conditional. Allison was special because she reflected well on mother.

When Allison expressed interest in art, her mother discouraged it: “Artists are poor; you’re too smart for that.” When she struggled with organic chemistry and considered changing majors, her mother reacted with fury: “How could you do this to me? I’ve already told everyone my daughter is going to be a doctor. What am I supposed to say now?”

Allison already knew her role was to serve as her mother’s vicarious achievement. She became her mother’s emotional confidante—listening to complaints about father, mediating parental conflicts, managing mother’s moods. By her teens Allison knew more about her mother’s emotional life than her mother knew about Allison’s.

This is parentification’s essence: the child’s mental world colonised by parental needs. The developing sense of self wraps around ‘What does mother need me to be?’ rather than ‘Who am I?’ If the farm only grows crops for others, the farmer starves no matter what the harvest.

Allison’s true self—the part that wanted to paint, that felt burdened by achievement pressure, that longed for a mother who could see her—remained in the dark. What flourished was a false self almost perfectly attuned to maternal requirements. She was everything her mother hoped, an extension of herself. Capable of performing excellence while feeling nothing that could compete or conflict with her. Achieving without any satisfaction. Performing without living.

The outcome is often narcissism—typically vulnerable, masked by grandiose defences. Overvaluation’s conditionality drives the mechanism: the golden child is special when they perform, when they achieve, when they make the parent look good. Aside from that they are worthless, nothing. The resulting persona combines entitlement with anxious insecurity. An all pervading terror.

Allison in therapy expressed this precisely: entitled expectations (‘I should be chief resident; the people chosen over me are clearly less qualified’), hypersensitivity to criticism (a senior attending’s feedback triggered days of rumination and rage), and underlying emptiness (“I don’t know what I actually want; I’ve spent my whole life in service to others”).

The clinician observed to her she couldn’t sustain intimate relationships because vulnerability felt like failure. She chose romantic partners based on status rather than connection, then felt contempt when they displayed ordinary human needs. This wasn’t what she sought.

The golden child transforms into a narcissist not despite the overvaluation but because of it—praise that reflects the parent’s needs, creating Winnicott’s false self built around complying with parental needs.

The scapegoat experiences the second Pathway’s devaluation, but with an additional dimension: they’re not just abused—they’re also blamed for the family’s dysfunction. Through Projective Identification Projective Identification A defense mechanism where one person projects unwanted parts of themselves onto another, then manipulates the other to behave in accordance with the projection. Common in narcissistic dynamics where victims come to feel the narcissist's disowned shame and inadequacy. , the narcissistic parent projects and thereby displaces their own shame and anger onto the scapegoat, along with envy, then tortures the child as if these qualities are the child’s actual characteristics. The poor child is caught in the bind of playing along and being hurt, or revealing they are different and being punished for lying, or deceiving a parent who can’t accept their child is not what they project. If hell is existence as torture; then this child is literally in hell.

Daniel, Allison’s younger brother, occupied this role. While Allison was praised for every hollow achievement, Daniel was criticised for every flaw. Report card with mostly A’s and one B? Mother focused exclusively on the B: “Why can’t you be more like your sister? She never disappoints me.” When Daniel asked for help with homework: “Figure it out yourself; I’m tired of your stupidity.” When the siblings fought, Daniel was invariably blamed regardless of what happened.

Most devastatingly: when the parents’ marriage deteriorated, Daniel was identified as the ‘problem child’ whose behaviour was ‘causing stress.’ Family therapy was sought not to address the parents’ relationship but to ‘fix Daniel.’ The implicit narrative: everything would be fine if Daniel were different.

This is projective identification at its most poisonous. The parent’s internal bad is externalised onto the child, who is then treated in ways that induce the very traits projected. Daniel, constantly criticised, became understandably oppositional and angry—confirming the mother’s narrative that he was the problem.

Yes, the scapegoat’s developmental path to narcissism differs from the golden child’s, but both stem from Winnicott’s 1333 failure of the ‘holding environment’. The scapegoat’s true self—the child who needed love, recognition, safety—was actively attacked. Two responses are thus forced into expression: identification with the projection (‘I am bad, worthless, the problem’) leading to depression and borderline organisation; or defensive rejection through reactive grandiosity (‘I’m not bad; they are; I don’t need them; I’m better than all of them’).

Daniel left home at 18 and severed contact. It was too late. By his late twenties, he exhibited narcissistic patterns: chronic anger, exploitation, inability to maintain relationships, contempt for authority. His narcissism was clearly vulnerable—brittle, compensatory, constantly threatened by the underlying shame of having been the family reject.

But unlike abuse from strangers, Daniel’s carried an additional burden: rejection by the people who should have loved him most, in favour of a sibling no more deserving—only more compliant. After-hours, her Hungarian clinician related that a colleague had picked up the brother as a client a few months earlier, and asked him for a case review. He had placed an informal wager for a six-pack of soda that the sister would be in therapy before the year was out. After listening to her, he said he’d lost his thirst for the soda. There was much work to be done.

Jensen’s research 606 confirmed why a favoured sibling’s presence amplifies the trauma. Daniel didn’t just experience rejection—he experienced it while watching Allison receive praise for comparable or lesser achievements. Everyone knew the unfairness, saw the concrete reality, embodied in the sibling who sat across from him at dinner receiving the literal food and nourishment he desperately needed.

The scapegoat child develops a fine sensitivity to comparative evaluation, always monitoring for evidence of differential treatment. Nothing is ever enough because the standard isn’t excellence—it’s that impossible task of displacing the golden child. This creates what we call the ‘unseen child’: growing up invisible in plain sight, authentic needs treated as inconvenient or threatening to the family’s equilibrium. It is the broken heart of this book.

The torture doesn’t just take place across siblings: the most damaging scenario occurs when a single child oscillates between golden and scapegoat roles.

Some narcissistic parents assign roles by developmental stage. A child might be golden in early childhood—cute, controllable, maximally available for mirroring—then become the scapegoat in adolescence when autonomy and sexuality—emerging identity itself—threaten parental control, triggering envy.

Others oscillate based on performance: golden when achieving, scapegoat when failing or expressing needs that require actual caregiving rather than admiration.

This shifting is particularly cruel. The child cannot develop a stable sense of self—special and worthless, idealised and despised, depending on the parent’s shifting requirements. They learn their value is conditional but cannot understand the conditions, because these depend on the parent’s internal states, not their own behaviour. The more arbitrary and cruel the shifts, the more desperately the child tries to fit back into them.

The resulting personality often shows the affective instability and identity diffusion of borderline disorder, sometimes combined with narcissistic symptoms. The child develops neither a stable false-self nor coherent sense of which self to maintain—only identity confusion and desperate attempts to elicit consistent mirroring from others. When parents fade, the void expands to fit the entire human universe. No escape exists.

Golden child, scapegoat, oscillating roles—it doesn’t matter which. What unites all variations of Pathway 3 is this: the child was never allowed to exist.

Schore’s psychobiological harmonisation never happens—the child sees their internal states as irrelevant or dangerous. Fonagy’s mentalisation is missing—the parent cannot wonder ‘What is my child experiencing?’ because that would mean acknowledging the child as independent and real. Winnicott’s ‘holding environment’ collapses—spontaneous gestures meet not responsive mirroring but demand for compliance.

The true self has no way to surface. It drowns. An elaborate false-self emerges instead.

The long-term damage isn’t just the narcissistic or borderline traits that develop. It’s the lasting alienation from the authentic self. The adult person who doesn’t know who they are apart from roles assigned in childhood. Who literally cannot distinguish their own feelings from the scripts they learned to perform.

Gene-Environment Interaction (The ‘Via’)

The Diathesis-Stress Model

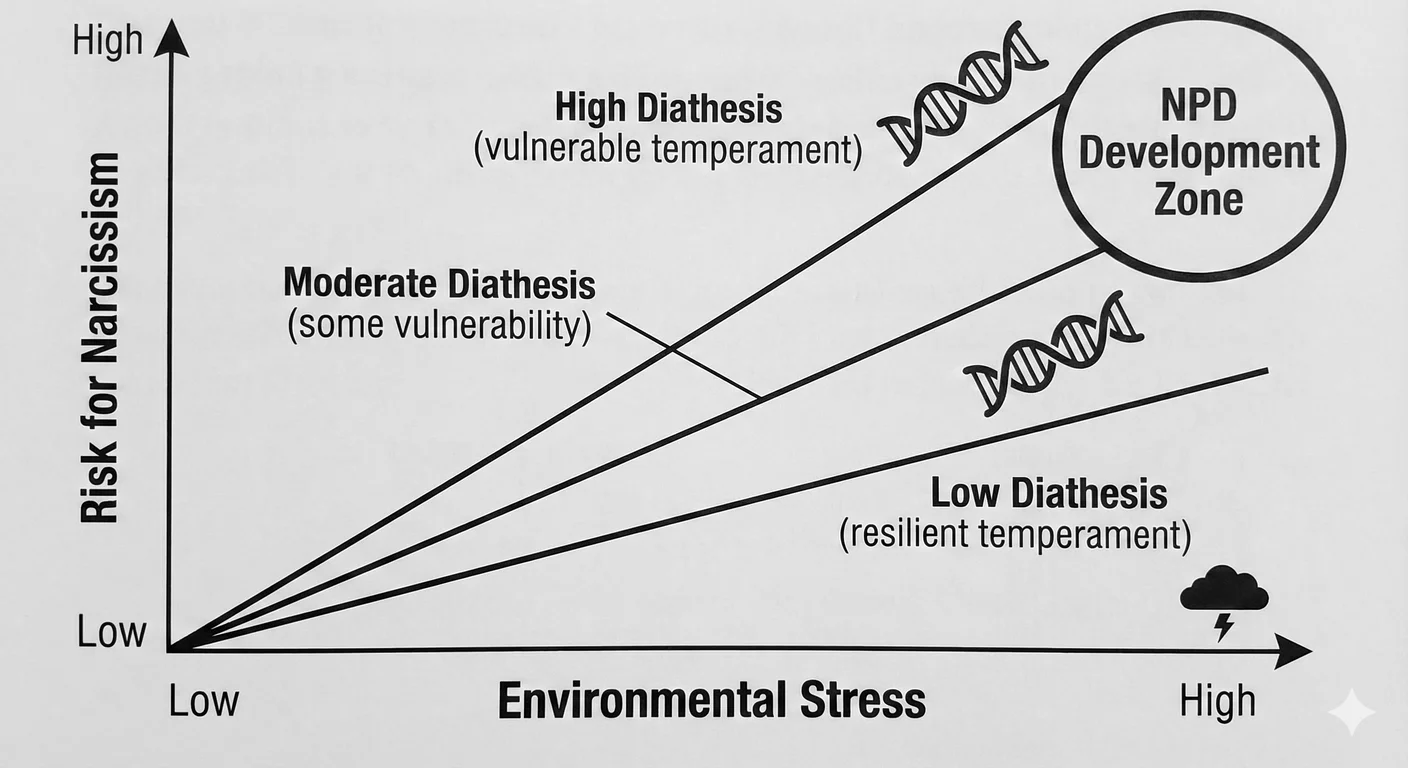

Heritable traits through genetics (which account for roughly half of the risk at 47-64% of narcissism variance), biological differences in the brain’s empathy and stress centres, and childhood experiences like over-praising or abuse—these might seem to contradict each other. People often ask: “Are narcissists born or made?” However, looking at it as a choice between “nature” or “nurture” is the central mistake. Genes and environment interact to cause narcissism. The “diathesis-stress model” shows that genes and life experiences don’t just add together; they multiply each other’s effects to create the disorder.

The Classical Diathesis-Stress Framework

The term ‘diathesis’ (from Greek, meaning ‘arrangement,’ ‘disposition,’ or ‘condition’) refers to a pre-existing vulnerability: the constellation of heritable temperamental traits, neurobiological peculiarities, and early developmental experiences that create susceptibility to disorder under stress. ‘Stress’ specifically refers to environmental triggers, adverse experiences, trauma, or developmental failures that activate the latent vulnerability. As Ingram and Luxton 591 articulate in their comprehensive 2005 review, the diathesis-stress model proposes that psychopathology results from the interaction between stable vulnerability factors (diatheses) and proximal stressors.

The formula is simple: Diathesis $\times$ Stress $=$ Disorder. The multiplication sign is essential, not decorative. Diathesis alone (the vulnerable temperament, the neurobiological substrate) produces risk, not actual narcissism. Environmental stress alone—narcissistic parenting, childhood abuse—does not always produce narcissism; many children exposed to such adversity do not develop personality disorder. Their interaction produces the disorder, each factor amplifying the other’s effect in ways neither could achieve independently 1373 882 . That’s the key finding.

Rutter 1071 , in his landmark synthesis “Genes and Behaviour: Nature-Nurture Interplay Explained,” demolished the lingering vestiges of nature-versus-nurture thinking by demonstrating that genes and environment do not operate as independent effects but engage in multiple forms of influential, radiative interplay. Rutter identified three mechanisms of gene-environment correlation (rGE): passive correlation (parents provide both genes and rearing environment), evocative correlation (child’s genetically influenced behaviour elicits specific environmental responses), and active correlation (individuals select environments concordant with their genotype). But beyond correlation, Rutter emphasised gene-environment interaction (GxE): genetic factors do not determine outcomes; they determine sensitivity to environmental input. A temperamental vulnerability is a conditional probability, activated or left dormant depending on environmental conditions encountered. People express to the world what the world makes them experience.

For narcissism, this framework helps resolve the contradiction. 950 Paris, applying diathesis-stress logic to personality disorders, clarified that a child with high temperamental reactivity—heightened sensitivity to criticism, difficulty regulating self-esteem, intense responses to perceived rejection—may still develop a healthy personality. If raised in a ‘good enough’ environment with parents capable of providing what Winnicott 1333 called adequate holding and mirroring, such a child may become sensitive, perhaps perfectionistic, but fundamentally healthy. This is a good outcome.

The diathesis exists, yes, but remains unactivated; the child’s vulnerability is met with local support that buffers rather than amplifies it. By the same token, a child with low temperamental vulnerability—resilient and emotionally stable, being less reactive—when exposed to narcissistic parenting may emerge with subclinical narcissistic traits, and have mild interpersonal difficulties, or even compensatory strategies, but will not necessarily get the full personality disorder. Less good news, true, but far better than the other outcomes. The environmental stress exists, yes, but encounters insufficient fertile ground to catalyse the narcissistic pathology because the child gives it less ground to grow.

The highest-risk scenario combines high diathesis and high stress: the vulnerable child—reactive and shame-prone—experiencing specific developmental failures. This unfortunate child inherits both the neurology predisposing to empathy deficits (reduced anterior insula grey matter) and stress dysregulation (the ‘vigilant brain’ in constant defensive alert) and encounters adverse conditions that activate and entrench these vulnerabilities into narcissistic personality structure. The narcissistic parent’s failure of mirroring meets the child’s genetically heightened need for external validation; the parent’s conditional regard meets the child’s temperamental difficulty regulating self-esteem; the parent’s empathy deficit meets the child’s neurobiological vulnerability in empathy circuits. The interaction proves not merely additive but synergistic: each factor exponentially increases the other’s destructive impact. A convergence of factors which accelerate and propel the creation of a narcissistic personality disorder.

Why Siblings in the Same Family Develop Differently

The diathesis-stress model explains the single most mystifying clinical observation confronting any environmental theory of narcissism: Why do siblings raised in the ‘same’ narcissistic family develop such radically different outcomes—one becoming narcissistic, another borderline, a third apparently resilient? Siblings do not actually share the same environment, even when raised by the same parents in the same household. Shared environment (family-wide atmosphere) accounts for literally 0% of variance in narcissism; non-shared environments (experiences unique to each child) account for 41-53%. This is because each child is their own separate world, and world building endeavour. This also makes sense within diathesis-stress logic, if we stop thinking of people as deterministic patterns (often an artefact of clinical and statistical detachment).

First, each child brings a different diathesis—different heritable temperamental vulnerabilities. Genetics is our lantern here. The twin study evidence proves that intrapersonal grandiosity (23% heritable) and interpersonal entitlement (35% heritable) show 92-93% genetic independence 756 ; siblings literally inherit different combinations of these trait vulnerabilities. One sibling may inherit heightened reactivity to criticism but low exploitativeness; another will inherit interpersonal callousness but stable self-esteem. Ask any sibling how like their siblings they are, and listen to the response from any family. The same narcissistic parent encounters fundamentally different temperamental profiles, forcing them into activating different pathways.

Second, the ‘shared’ environment is not actually shared. That’s great on paper, but at home the narcissistic parent assigns children to different roles, golden child versus scapegoat, as detailed, providing radically different environmental inputs in what is clinically the same environment. The golden child receives hollow praise and overvaluation (activating grandiose pathway); the scapegoat receives devaluation and neglect (activating vulnerable/defensive pathway). Siblings experience the ‘same’ parent as functionally different parents. This is evocative gene-environment correlation 598 : the child’s inherited nature elicits different parenting responses, amplifying the initial temperamental differences. The difficult, reactive child triggers parental frustration and harshness; the compliant, easy child elicits less negative parenting. Each child’s genotype actively, albeit unconsciously, shapes their experienced environment.

Third, siblings occupy different developmental niches within any family ecosystem. Both McHale 838 and Jensen 606 studies document sibling differential treatment as normative: parents always treat children somewhat differently based on birth order and personality. We find this in every culture, at all levels of society. In narcissistic families, this normal variation may be extreme and pathogenic, but the underlying mechanism—non-shared environment created by differential treatment—operates universally. The first child may bear the brunt of the narcissistic parent’s unmet needs; the second may benefit from parental exhaustion, with the first child acting as a buffer or shield; the third will be emotionally neglected as the parent focuses elsewhere for supply and demolishing resistance. Each child’s subjective experience of the family changes dramatically based on temperament and developmental stage at which key events occurred, as well. The 7th birthday party meltdown for one child is felt differently by older and younger siblings based on their assigned roles.

The case from the introduction illustrates this perfectly: Maria had a brother, raised by the same mother struggling with addiction and instability. Maria, despite temperamental sensitivity, developed notable resilience and empathy—she transformed into a social worker dedicated to protecting children. Her brother, perhaps inheriting different genetic variants or occupying a different developmental niche in the family system, developed vulnerable narcissism. Same mother, same house, yet different diatheses produced different experienced environments and finally different outcomes. The diathesis-stress model predicts precisely this pattern: siblings sharing 50% of genes and ostensibly 100% of family environment show widely divergent outcomes because neither genes nor environment operate in isolation, only in interaction.

From Diathesis-Stress to Differential Susceptibility

Psychiatry spends a lot of time looking for answers, but doesn’t like them when they arrive. Recent theoretical and empirical studies are already challenging the diathesis-stress model’s implicit assumption that vulnerability factors are unidirectionally harmful. Belsky in 2009 103 proposed the differential susceptibility hypothesis, another wonderfully opaque term arguing that genetic and temperamental factors labelled ‘vulnerabilities’ should be ‘reconceptualised’ as ‘plasticity genes’ or ‘plasticity factors.’ This seems as much a rebranding as it does an attempt at advance. Individuals carrying these variants are more susceptible to environmental influence in general: ‘for better and for worse.’ Is this more than a restatement? This reframing cognitive restructuring tries to account for empirical observations inconsistent with diathesis-stress logic: in multiple studies, individuals with supposed ‘risk’ alleles show worse outcomes under adversity but also better outcomes under supportive conditions compared to individuals without these alleles. Belsky’s point is that these aren’t simply ‘vulnerabilities’—there are times when the changeability they present is an active boon.

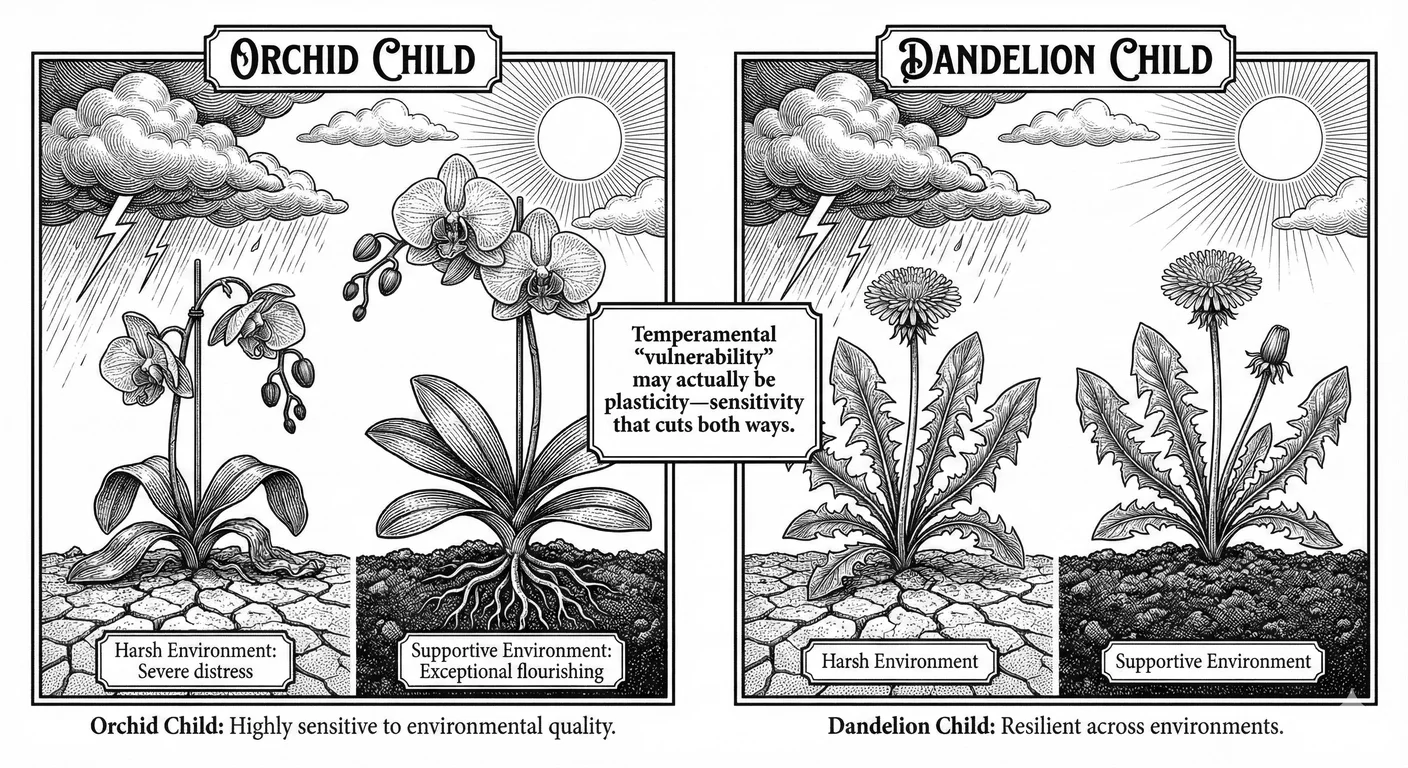

Boyce and Ellis 149 introduced the complementary framework of biological sensitivity to context, drawing on Swedish idioms of ‘orkidebarn’ (orchid child) and ‘maskrosbarn’ (dandelion child). Dandelion children, constituting the majority, are relatively hardy, resilient, and so able to develop adequately across a range of environmental conditions—neither devastated by adversity nor particularly enhanced by enrichment. Orchid children, neurobiologically sensitive and reactive, are akin to their flowers, sensitive to environmental quality: they wilt more obviously in harsh conditions (with high stress reactivity, and poor developmental outcomes) but flourish spectacularly in supportive conditions (exceptional creativity and empathy, emotional depth). Boyce and colleagues documented this empirically in studies of respiratory illness: children with high cardiovascular or immune reactivity showed highest rates of asthma in adverse family environments but lowest rates in supportive environments. The same biological ‘vulnerability’ predicts best and worst outcomes depending on environmental context. In all cases kindness and a genuinely loving environment led to better outcomes.

Applied to narcissism, diatheses can function as plasticity, not just vulnerability. The reactive, sensitive child exposed to narcissistic parenting (lacking mirroring, receiving conditional regard, experiencing empathic failures) ironically develops narcissistic traits to manage intolerable affect. But the same reactive, sensitive child raised by parents capable of good enough attunement, who validate the child’s authentic emotional experience, provide consistent mirroring, offer unconditional positive regard—may develop into an exceptionally empathic, emotionally attuned adult because their sensitive heart makes them more responsive to parental input. The ‘vulnerable’ child is more developmentally plastic, more thoroughly malleable, in either adaptive or maladaptive directions, by environmental quality.