I am a series of small victories and large defeats and I am as amazed as any other that I have gotten from there to here.

— Charles Bukowski, The People Look Like Flowers At Last

The Abandonment Core

A terror so overwhelming it organises every aspect of experience lies at Borderline Personality Disorder Borderline Personality Disorder A personality disorder characterized by emotional instability, intense fear of abandonment, unstable relationships, and identity disturbance. Often develops from childhood trauma and shares overlaps with narcissistic abuse effects. ’s heart: abandonment. 504 The threat feels like annihilation—like a baby who cries and cries until realisation hits, beyond words, that no one is coming. Where the narcissist fears exposure of their False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. , the borderline fears death of any self at all. This core terror is why borderline personality disorder became narcissism’s anxious sibling, sharing the same developmental wounds, but coping through desperate attachment rather than grandiose detachment.

Mia, recently diagnosed, describes it: “When my boyfriend is five minutes late, I don’t think he’s stuck in traffic. I know he’s left me. My body knows it before my mind—my chest caves in, I can’t breathe, everything goes dark. It’s not normal feeling that way; it’s more than fear. I’m totally sure it’s over, it’s dead, it was a lie, the life I cling on to is already gone, dissolved, nothing. Then he walks in and I hate him for putting me through that death.” This is the experience of actual loss before it occurs. 506

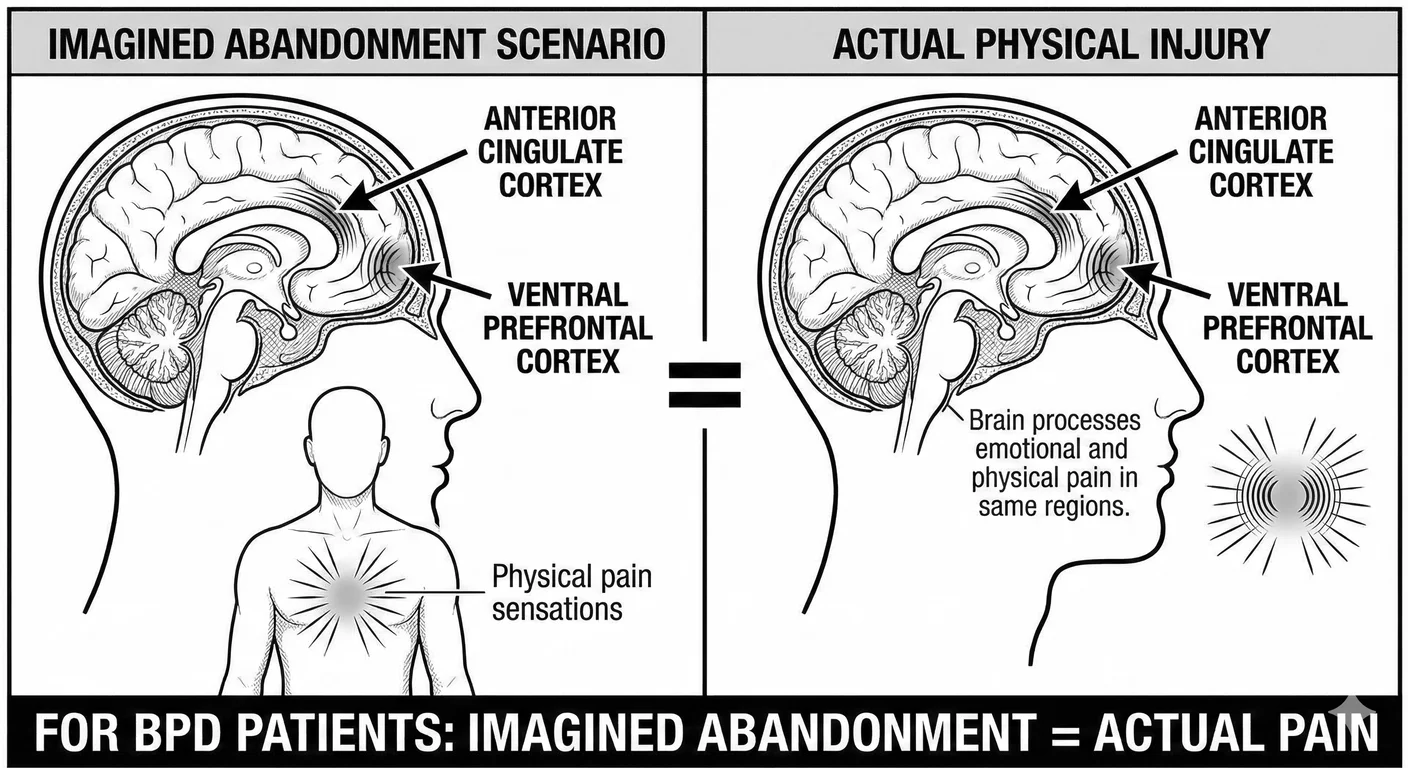

This fear’s somatic, bodily dimension is harrowing. People with BPD do not just think about abandonment; they feel it everywhere, visceral and totally real. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies demonstrate that imagining these scenarios activates not just emotional centres but actual pain processing regions; the anterior cingulate cortex and right ventral prefrontal cortex light up as if experiencing physical injury. The phrase “heartbreak” is not metaphorical for such people; social rejection actually registers as physical pain. Abandonment fears trigger such extreme behavioural responses because the person is responding to genuine agony. 356 This surprises many people.

It gets worse. Past losses feel perpetually present; they experience future abandonments as current reality, not fears. Patients describe feeling trapped, as if at the bottom of a well. Each potential abandonment carries the cumulative weight of all abandonments across time. 1361

Abandonment fears come to dominate every aspect of borderline life. Career choices prioritise security over satisfaction. A doctor with a promising career in London takes a job at the other end of the country to stay near her troubled family, abandoning colleagues and a promising romantic partner. Borderlines often remain in harmful situations rather than face solitude, gravitating naturally to jobs with shifts and rosters—any structure that avoids aloneness. 504

This terror of abandonment drives them into a “borderline dilemma,” the need for and fear of closeness. 817 Intimacy is protection against abandonment, yet intimacy itself triggers those same abandonment fears. The closer someone gets, the more devastating their potential loss would be. It’s tense. It’s explosive. The characteristic push-pull dynamic results: pulling others close for safety, pushing them away harder to prevent eventual abandonment. The borderline is trapped between equally terrifying options—engulfment or abandonment.

Contrast this with narcissistic abandonment responses. When relationships end, narcissists experience Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. —a wound to pride and loss of supply. They might rage or seek revenge, act out in some attention-seeking way, but they do not experience existential dissolution. The narcissist’s False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. and its mechanical grandiosity create pseudo-independence: “I never needed them anyway.” Their loss is real but it is a practical issue, like filling up the gas tank at a station. The borderline’s pain is total, threatening the very sense of being. The relationship is an essential part of what establishes their role, their secure place in the world. Losing a job, a husband, a house, access to family, feels very much like losing a living part of themselves, if not themselves entirely. 649

If Narcissus was narcissistic, then Echo—who could only repeat others’ words, who had no voice of her own, who wasted away when her love was rejected until nothing remained but sound—was borderline. She is the perfect myth for borderline pathology: a self that exists only as reflection, that dissolves without another to mirror.

Origins in Disorganised Attachment

BPD emerges from disorganised attachment—the most severe kind of insecure attachment. 732 While narcissistic personality disorder often develops from being treated as an extension of the parent, borderline comes from caregivers who were both source of comfort and unrelenting threat, creating an impossible bind for the developing infant.

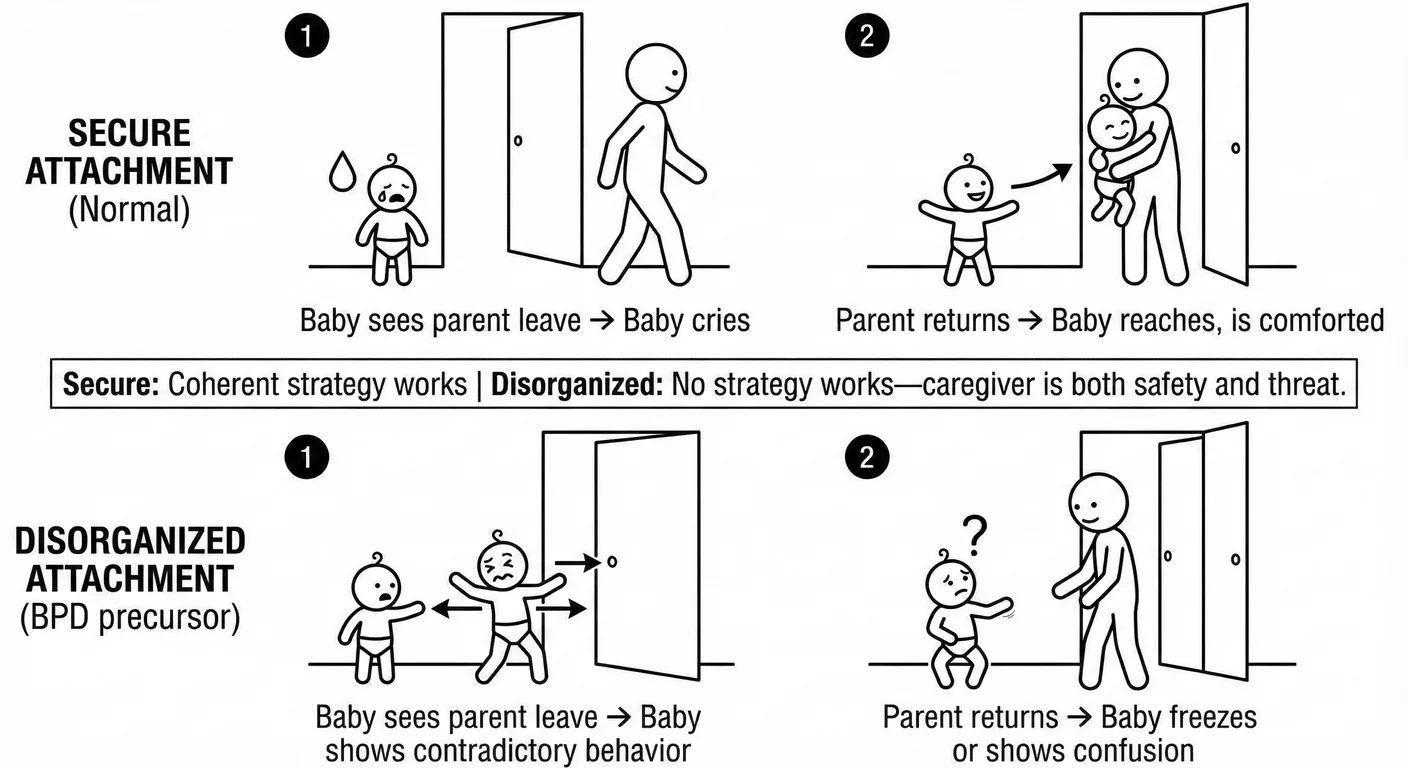

Mary Main’s research on disorganised attachment is difficult to watch. The videos show infants crawling towards their mother while looking away, as if approaching a cliff edge. They freeze mid-approach, hands outstretched, faces blank with confusion. One famous clip shows a toddler circling her mother in a wide arc, never getting closer than three feet, orbiting like a satellite that cannot land. These children cannot develop a coherent strategy for managing attachment needs because no strategy works. Go to mother and she might hurt you. Stay away and you might die. The infant’s entire being is forced to hedge. 785

The Strange Situation Procedure captures disorganised attachment in twenty minutes. Mother leaves. The secure infant cries, reaches for the door. Mother returns. The secure infant reaches for her, is comforted, returns to play. The disorganised infant does something else. Mother leaves and the child reaches towards the door while backing away from it. Mother returns and the child approaches sideways, or freezes completely, or—in the clips that stay with you—enters a trancelike state, dissociating before the very person meant to provide safety. One video shows a fourteen-month-old girl who, when her mother returns, walks toward her with arms outstretched but face turned completely away, as if her body is trying to go somewhere her mind cannot follow. She reaches her mother’s legs, stops, and begins hitting herself in the face. The mother does nothing. The hitting continues, rhythmic and mechanical, while the girl stares at the wall. Researchers watching these tapes for the first time often need breaks. The wrongness is visceral. 786 These children grow up trying to stay behind the parent, out of eye-line. They flinch when unexpectedly approached. The terror never leaves. It just goes underground.

Caregiver behaviours creating disorganised attachment read like a blueprint for borderline development. Frightened or frightening behaviour—parents who are themselves traumatised and dissociate during caregiving. Role confusion—parents who seek comfort from their children, parentifying them one moment, infantilising them the next, stretching the child’s being beyond tearing point. These patterns teach the little one that attachment itself is dangerous, yet necessary for survival. 772

And of course it gets trickier, as not all disorganising caregiving involves obvious abuse. Sometimes the trauma is the echo of the caregiver’s trauma—a postpartum depressed mother who dissociates while holding her baby, or a father whose unresolved trauma triggers sudden shutdown or uncontrollable rage. The infant experiences these ruptures as what they are: genuinely life-threatening, and while the parent may not actually intend any harm, the attachment system that should provide safety instead properly triggers alarm. In extended families, other adults come running to the cry to offer support, comfort, safety. In modern isolated nuclear families, this is not possible. Inevitably, the hidden trauma is harder to identify and treat than obvious abuse. 339 Shame stains the future.

Studies following disorganised infants into adulthood confirm the damage. Minnesota’s Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation tracked disorganised infants for over 30 years. By adolescence, 40-60 percent showed borderline features. By early adulthood, many met the full criteria for BPD. The disorganised infant who could not develop a coherent attachment strategy invariably becomes the adult who cannot maintain stable relationships. The approach-avoidance conflict visible in infancy hardens into the adult pattern of clinging and rejection. The inability to depend on any caregiver for emotional regulation becomes chronic emotional dysregulation. 201

Early trauma directly reshapes the brain. The prefrontal cortex, which should develop capacities for emotional regulation, is visibly smaller in individuals with borderline histories. The amygdala shows hyperactivity—always scanning for threat—while the hippocampus shows structural abnormalities that contribute to the dissociative symptoms common in BPD, preventing the normal encoding of moments into a healthy time stream. These brain changes are not destiny, but they show how early relational trauma literally reshapes neural architecture. 1219

Identity Diffusion

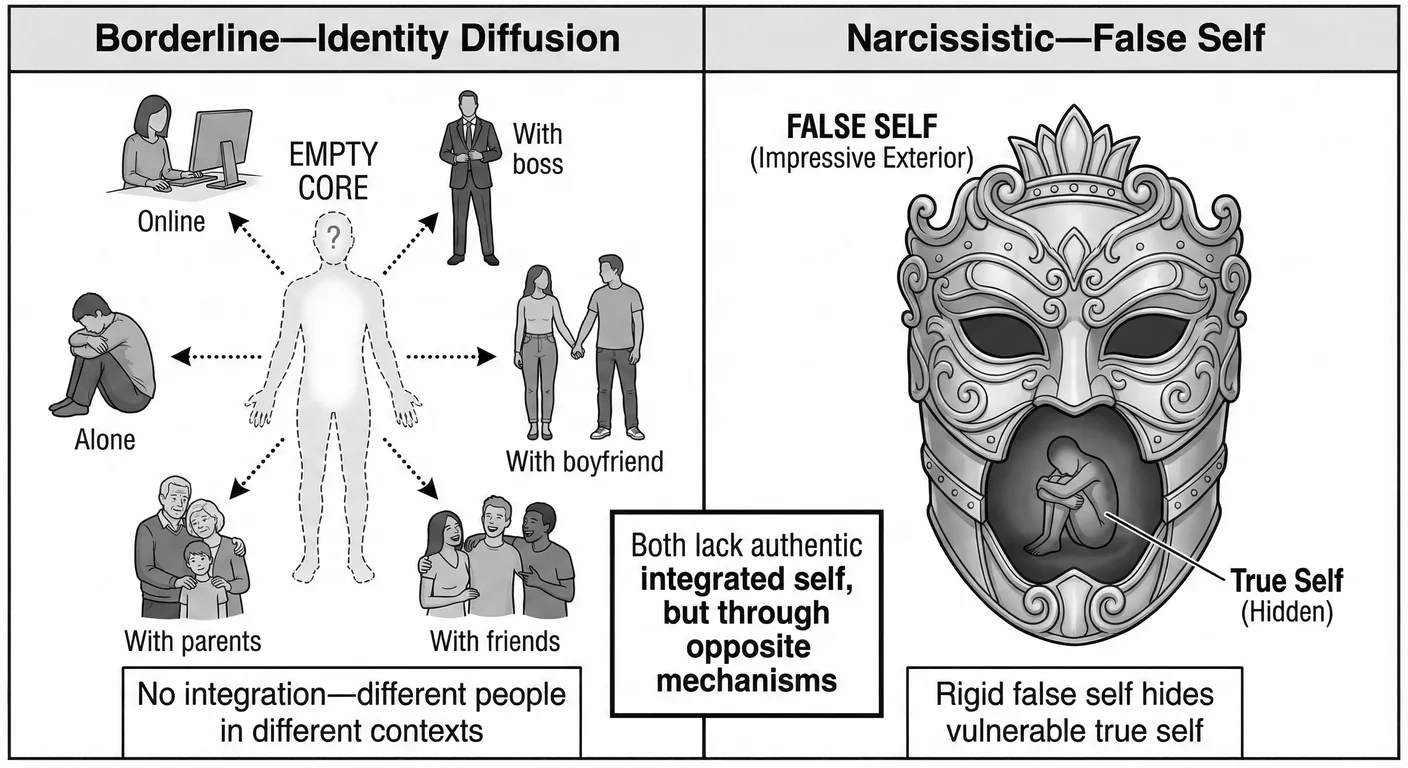

If fear of abandonment lays the foundation of borderline, Identity Diffusion Identity Diffusion A poorly integrated or unstable sense of self, characterized by confusion about who you are, what you value, and what you want. Common in personality disorders and in survivors of narcissistic abuse who were never allowed to develop autonomous identities. becomes its cognitive structure. 650 This chronic inability to develop an integrated sense of self distinguishes borderline from the other personality disorders. While narcissists have a false self, borderlines often have no stable self at all, just shifting fragments that reorganise based on interpersonal context. They literally change who they are based on whom they are with.

Rachel, a model working in New York, describes her identity confusion as she preps for her latest show: “I don’t know who I am. It’s not that I’m unsure or figuring it out—I literally have no idea. When I’m with different people, I become different people. With my boss, I’m competent and professional. With my boyfriend, I’m really needy and quite emotional. But none of these feel like, me. You know? It’s like… I’m acting roles without anything underneath. They’re like clothes in shows. Sometimes I look in the mirror and do not recognise myself. Not a joke—I sometimes need an actual beat to realise it’s actually me looking back. She’s someone else until I look long enough to realise it’s me.”

Healthy identity development involves trying different roles while keeping one’s continuity of self. Teenagers experiment with styles and relationships throughout various stages but know they are the same person across situations. Borderlines do not. Every role is its own thing, and they can only park in it for so long. They are not trying on different selves; they become different selves, with no core self providing integration, and no hope of maintaining them.

BPD’s diagnostic criteria capture this: markedly unstable self-image and chronic feelings of emptiness. 34 Each criterion reflects identity diffusion—unstable self-image because there is no stable self to image, chronic emptiness because no self fills the void. The relationships are unstable because different selves emerge with different people, and none of them can hold.

Neuroimaging studies highlight the centres of identity diffusion. When viewing their own faces, borderlines show decreased activation in self-recognition areas compared to healthy controls. They literally process their own image less as “self.” When making self-referential judgements (“Am I kind?”), they show increased activation in areas associated with uncertainty and conflict. The borderline brain struggles with the basic task of self-recognition and self-knowledge. 98 They cannot see themselves as anything other than echoes—which is perhaps why Echo’s myth resonates so deeply. She had no original voice; borderlines have no original self.

The Narcissistic Contrast

While borderline is an echo with too little real self, the narcissist has too much of their false-self. Darnell, an Uber driver in New York, offers unsolicited life advice as we approach Grand Central: “See, the problem with most people is they don’t understand value. I’m driving Uber temporarily—between ventures. I’ve had businesses, real estate, consulting. People always want my opinion because I see things others miss. My ex? She couldn’t handle being with someone operating at my level. Most people can’t.” He has not asked a single question about his passenger. When the conversation turns to setbacks—a business that failed, the divorce—his tone shifts: “That wasn’t failure. That was other people not executing my vision. The market wasn’t ready. She wasn’t ready.” The grandiosity emerges not as boast but as frame: everything is interpreted through the lens of his superiority.

At a red light, something crosses his face—a flicker, quickly suppressed. “My daughter doesn’t talk to me anymore. Her mother poisoned her against me.” He says it flatly, as fact, but his hands tighten on the wheel. “I was building something. I was going to give her everything. But they couldn’t see it. Nobody could see it.” For a moment, the mask slips—not into vulnerability, but into something harder, a cold fury at a world that refuses to recognise what he knows himself to be. Then the light changes, and the salesman voice returns: “Anyway. You want some advice? Never let anyone define your limits. That’s what I tell my mentees.”

The certainty requires constant maintenance. It cannot withstand examination. And underneath it—visible only in the moments when the performance falters—is not emptiness, like the borderline’s void, but something more like a clenched fist. The narcissist knows, somewhere beneath knowing, that the grandiose self is a construction. The construction must never fall. The fist must never unclench.

This false self achieves what borderline identity diffusion cannot: predictability and apparent coherence. The narcissist always knows how to act and what to want because the false self operates like a “lookup table”. But this stability is brittle; one significant failure can expose the entire conceit. 649

These complementary structures create powerful mutual attraction. The borderline person, lacking identity, finds in the narcissist’s apparent false self exactly what they seek: solidity. The narcissist finds in the borderline’s identity diffusion a flexibility perfect for Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. —a devoted admirer who will become whoever they need. This codependency feels like “destiny” but is actually pathology. 698

Emotional Dysregulation Compared

Wild mood swings that stigmatise borderlines contrast sharply with narcissistic emotional patterns. Borderlines experience emotions as entire changes in their very field of being; narcissists experience emotions as threats to be defended against—shot down, managed, or projected.

The Borderline Emotional Storm

Borderline emotional instability is among psychiatry’s most dramatic phenomena. Emotions are not merely intense; they are totalitarian, commandeering every aspect of experience. Partners describe the disorientation: “It’s like living with the weather,” one husband said. “Sunshine one minute, hurricane the next, and I’m always somehow responsible for both.”

Conversations become minefields. The borderline typically does not feel heard or seen. They lean into and amplify the feelings of their situation. A partner’s mild irritation becomes their rage. A minor, fleeting look of sorrow becomes their failure and leads to weeping, and begging their partner not to walk out on them. This is not acting; it is real pain, and so they need compassion, need to be held, to feel stable and secure. It is intense emotional labour for their partner. Marsha Linehan, who developed Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) specifically for BPD, describes borderline individuals as “emotional burn victims”, lacking the protective emotional skin that allows others to modulate feeling. Every emotional stimulus creates agony. 748

Tommy rolls himself a smoke as he leans outside a Wetherspoons in Denton: “When I feel it, I become it. Anger isn’t something I have; I am rage. I am raging. Sadness ain’t a feeling, mate; total metal despair. Joy isn’t just Disney happiness; it’s manic highlander lightning that might kill me as I become immortal. It drowns me, man, the emotion is everything.” Neuroimaging confirms Tommy’s truthfulness: during emotional activation, borderlines show decreased activity in self-awareness regions and increased activity in emotional centres. They neurologically lose themselves in emotion. 1105

Borderline emotions detonate like grenades throughout the day—a neutral comment triggers immediate rage, a minor disappointment provokes suicidal despair, with real self-harm risk. Peak intensity is reached within seconds. What would be a five-minute annoyance for others becomes a five-hour fury; the emotional system never fully resets. 344

While causing tremendous suffering, the wild mood instability achieves a purpose. Without a stable self, intense emotions provide something to organise around: “I suffer, therefore I am.” The storms communicate desperate needs that cannot be articulated verbally. Self-harm regulates unbearable emotional states through physical pain that paradoxically soothes. These are not just symptoms but survival strategies—understanding them is essential for treatment. 231

Yet, ask anyone in a BPD relationship, of any sort, and the impact of their storms is devastating. Partners and family describe living in constant vigilance, never knowing what will trigger an explosion. “Walking on eggshells” transforms into a way of life. The borderline’s emotions become the organising principle of relationships—everyone mobilises to manage storms. This gives the borderline temporary power but leads to ultimate isolation, as others burn out and withdraw. The very intensity meant to maintain connection drives others away. 505

The Narcissistic Emotional Fortress

Where borderlines are consumed by emotions, narcissists fortress against them. 1048 Ask a narcissist about their feelings and watch the deflection: “I don’t really do emotions”—said with pride, as though describing an accomplishment. Depression is weakness. Anxiety is for lesser people. Vulnerability is contemptible. They experience emotional life not as rich inner terrain but as threat to manage, weakness to hide, ammunition others might use.

Consider rage: borderline rage is hot, lava-like, desperate—often followed by genuine remorse (“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean it, please don’t leave”). Narcissistic rage is cold and self-righteous, never genuinely remorseful (“You made me do this by failing to recognise my importance”). Borderline rage seeks to prevent abandonment; narcissistic rage punishes insult to grandiosity. 649

Emotional Contagion and Boundaries

Emotions lend meaning to experiences and their healthy interplay informs and enriches the self. BPD individuals have no ‘skin’ when it comes to feeling—everything is raw and visceral, overwhelming—while NPD individuals evade emotions or regard them as signs of weakness threatening their constructed image. That dynamic powers some of the most pathological behaviours when the two share the same situation.

Borderline people show incredible emotional contagion—they “catch” others’ emotions instantly and intensely. In a room with an angry person, the borderline becomes angry. Near someone sad, they are overwhelmed with grief. This is not real empathy in the sense that healthy people know it; up close and personal, it seems to be genuinely a violation of boundaries and an attempt to absorb others’ selves into their void of self. The borderline cannot maintain boundaries between self and other emotions, partly because they lack a stable self to maintain boundaries around. Others’ emotions consequently flood in and become their own. 315 This can feel incredibly strange in real life, as your own authentic emotions and response can feel “stolen” or “hijacked” by a nearby BPD person.

This same emotional permeability makes borderlines supremely sensitive to interpersonal atmospheres. They will detect micro-expressions and tonal shifts others miss. This sensitivity could be a gift in normal circumstances, yet without emotional boundaries, it becomes a curse. The borderline is lost in the churning emotional soup of their environment. Group therapy is often overwhelming as a result; crowded spaces unbearable. They are flooded by everyone’s emotions while their own intensity overwhelms those directly around them. 913

Narcissists show complementary patterns—a hardened sealed outer shell that prevents genuine emotional exchange. They neither catch others’ emotions nor allow their own authentic feelings to be accessed. The narcissist might intellectually recognise that someone is sad, but does not feel moved. It is akin to noticing a trend on a spreadsheet. They might strategically display emotion for effect, but do not share genuine feeling at all. This emotional indirection prevents any real intimacy. Others feel lonely in relationship with narcissists because no true emotional contact occurs. 1037

When borderline emotional contagion meets narcissistic indirection, destructive dynamics emerge. The borderline desperately broadcasts emotional intensity, seeking connection. The narcissist could not care less, perhaps is even contemptuous: “You’re being dramatic.” This rejection triggers borderline escalation, more intensity, more desperate attempts at emotional contact. The narcissist withdraws or attacks: “You’re crazy, too much.” The borderline experiences this new rejection as abandonment, confirming their worst fears. Neither can actually provide what the other needs: the borderline cannot navigate the narcissist’s emotional maze; the narcissist is unable to face the borderline’s genuine emotion. 699

Defence Mechanisms

Both disorders rely on primitive childhood defences, but borderline defences are chaotic: Splitting Splitting A psychological defence mechanism involving all-or-nothing thinking where people or situations are seen as entirely good or entirely bad, with no middle ground. cycles rapidly, and Projective Identification Projective Identification A defense mechanism where one person projects unwanted parts of themselves onto another, then manipulates the other to behave in accordance with the projection. Common in narcissistic dynamics where victims come to feel the narcissist's disowned shame and inadequacy. induces in others the feelings the borderline cannot tolerate. Narcissistic defences are more stable, maintaining the false self through cycles of idealisation and devaluation that keep the narcissist in control. 650

A therapist in Bristol described watching these defences collide in a couples session. The borderline partner had discovered a flirtatious text on her husband’s phone—nothing definitive, but enough. In the session, she oscillated wildly: one moment he was evil, a monster, she had always known he would betray her; the next moment she was the problem, too jealous, too crazy, she was destroying everything good in her life. The splitting happened in real time, the husband transforming from villain to victim and back every few minutes. Meanwhile, the narcissistic husband sat perfectly still, face composed, radiating wounded dignity. “I can’t control what she feels,” he said calmly. “I’ve done nothing wrong. If she chooses to interpret an innocent conversation as betrayal, that’s her pathology, not mine.” He was projecting his guilt outward while disidentifying from it completely—the text existed, his flirtation was real, but in his telling the problem had become entirely her perception. By the session’s end, the therapist noticed something unsettling: she herself felt vaguely guilty, as if she had done something wrong. The borderline’s projective identification had worked—the unbearable feeling had been successfully transferred. The room was saturated with displaced emotion that belonged to no one and everyone.

One narcissistic defence deserves particular attention: projective dis-identification. Unlike projective identification, this involves attributing one’s own unacceptable qualities to others while maintaining conscious distance, literally shedding parts of their identity to distract and distance themselves from negativity. In so doing the narcissist can project their own manipulation onto others (“Everyone’s trying to use me”) while remaining unaware of their own exploitative behaviour. 1180

The Relationship Dance

Borderline and narcissistic pathologies complement each other, creating among psychology’s most intense and difficult-to-escape relationship patterns—“Fatal Attraction” in real life.

The Initial Idealisation

Emma (borderline) describes meeting David (narcissistic): “The moment I met him, I knew he was different. He was so confident and clear about what he wanted. I’d been drifting, lost, empty, and suddenly here was this person who knew exactly who he was and where he was going. When he looked at me, I felt real for the first time. When he said I was special, I believed it because he was special. I didn’t just fall in love—I found myself in him.”

David describes the same meeting: “She was mesmerised by me from the start. The way she looked at me, like I was a god. She hung on every word and agreed with every opinion. She told me I was the most amazing person she had ever met, and unlike others who say that, she meant it completely. She became whatever I needed—sexy or intellectual, always admiring. It was like she was custom-made for me.”

Neurochemistry resembles addiction. Functional MRI studies show activation in the ventral tegmental area and caudate nucleus—the same regions cocaine activates. Dopamine floods reward circuits; meanwhile serotonin drops, leading to intrusive thinking about the partner. They literally become addicted to each other. 391

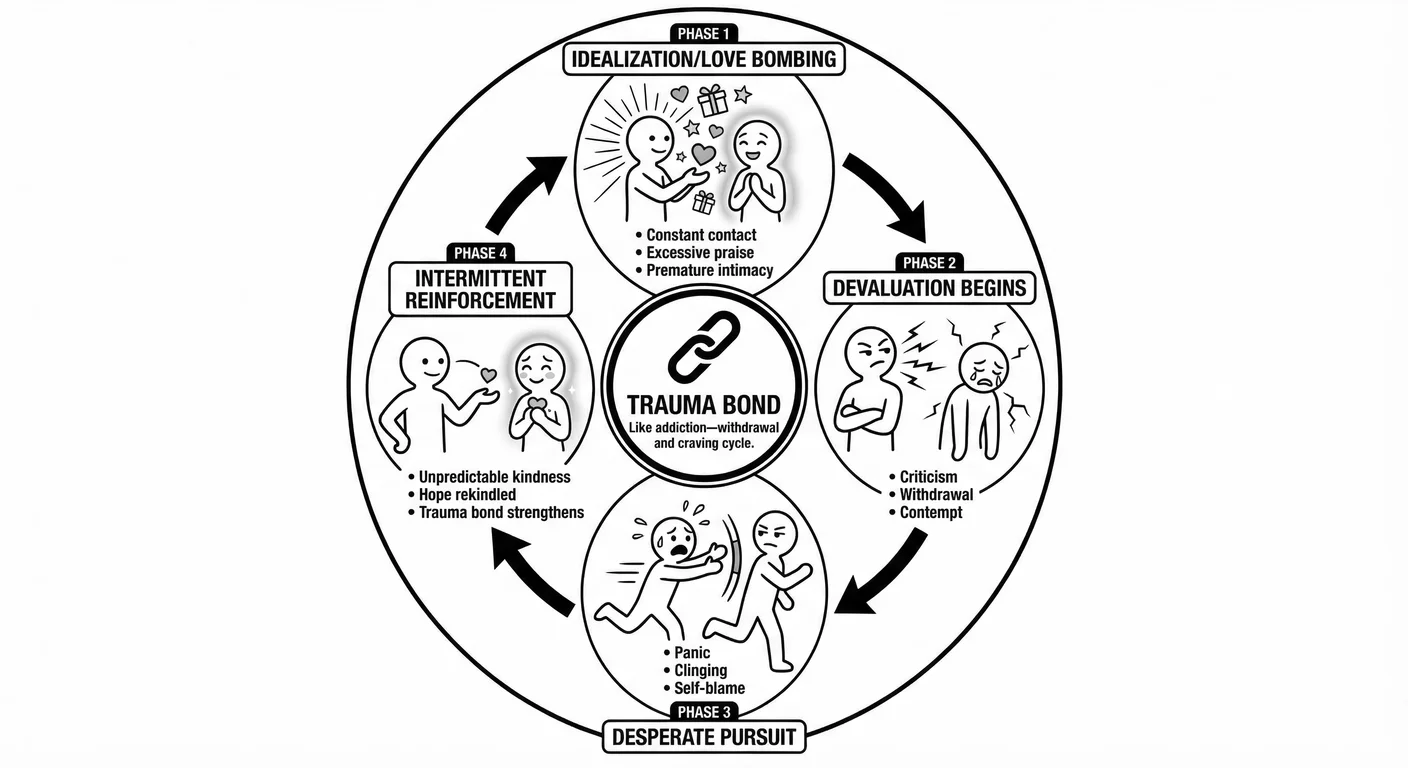

“ Love Bombing Love Bombing An overwhelming display of attention, affection, and adoration early in a relationship designed to create rapid emotional dependency and attachment. ” takes on particular poignancy. The narcissist overwhelms: constant texting, elaborate gifts, premature declarations of love, discussions of marriage within weeks. For the borderline, every text proves they have not been abandoned, every gift confirms their worth. The intensity matches their internal emotional state, making it feel “right” in ways healthy relationships never do. 42

The Inevitable Devaluation

The borderline’s needs quickly overwhelm the narcissist’s limited capacity for even cognitive empathy. The narcissist’s emotional flatness triggers the borderline’s abandonment fears. What seemed like perfect completion reveals itself as mutual exploitation. The timing varies, weeks to months typically, but the outcome is always the same.

The first cracks often appear around the borderline’s emotional intensity. Initially flattering, “She feels everything so deeply”, it becomes burdensome: “She’s too much, too emotional, too needy.” The narcissist withdraws from emotional episodes they can neither understand nor tolerate. This withdrawal triggers borderline abandonment panic, creating desperate pursuit that further repels the narcissist. The dance of pursuit and withdrawal begins, each step confirming the other’s worst fears. 812

That dinner was the first crack. Over the following months, the pattern intensified. Emma’s abandonment panic escalated—if David was five minutes late, she accused him of cheating; if he wanted an evening alone, she threatened self-harm. David’s contempt calcified. “She made me feel trapped,” he said later. “Me? I never needed anyone, let alone her.”

Devaluation follows predictable, almost banal stages. First comes irritation, then criticism, then contempt—the ultimate relationship killer. The narcissist views the borderline with disgust; the borderline sees the narcissist as evil. 478

The narcissist enters relationships expecting unlimited admiration. Sometimes they call it “unconditional love.” When the borderline, consumed by their own needs, fails to provide it in the form of constant supply, the narcissist experiences this as betrayal. The borderline’s needs do not just inconvenience the narcissist; they threaten their inner structure. If the individual has to provide care, they are not superior. This intolerable position triggers devaluation. 649

Borderlines experience devaluation as particularly devastating. Having found identity in the narcissist, devaluation threatens not just the relationship but the self. Emma continues: “When he stopped seeing me as special, I stopped existing. I would look in the mirror and see nothing. I would try to remember who I was before him, but there was no before, just emptiness. I became desperate, doing anything to get back to how we were—dressing how he liked or being whoever he needed. But it was never enough. The more I tried, the more disgusted he looked.”

The Trauma Bond

This cycling between idealisation and devaluation creates Trauma Bonding Trauma Bonding A powerful emotional attachment formed between an abuse victim and their abuser through cycles of intermittent abuse and positive reinforcement. through Intermittent Reinforcement Intermittent Reinforcement An unpredictable pattern of rewards and punishments that creates powerful psychological dependency, making abusive relationships extremely difficult to leave. of reward and punishment—a mechanism similar to Stockholm Syndrome. 341

Intermittent reinforcement is the most powerful form of behavioural conditioning. 1146 In healthy relationships, love and care are relatively consistent, creating secure attachment. Both parties know the love and care are there, and will be, whatever the current ripples may be—the boat will not sink.

In traumatic relationships, periods of intense affection alternate unpredictably with cruelty, creating powerful addiction. The borderline never truly knows if they will get the loving partner or the cruel one, so they stay ever vigilant, always trying to earn the good treatment. Each moment of kindness after cruelty creates intense relief and gratitude, bonding them more deeply than consistent kindness ever could.

The neurochemistry resembles addiction withdrawal. During reward periods, dopamine floods the system; during cruel periods, dopamine crashes, creating desperate craving for the next relief. It is not love they seek but escape. Ironically, the borderline becomes physiologically dependent on the narcissist’s approval signals. Attempting to leave triggers withdrawal symptoms: anxiety, depression, physical pain, obsessive thinking. Many borderlines report that staying in abuse feels simpler than enduring withdrawal.

Shame plays a central role in maintaining artificial trauma bonds. The borderline feels genuinely ashamed of their neediness and inability to leave, as any person would. They hide the relationship’s reality from others, isolating themselves further. The narcissist exploits this shame: “If you weren’t so crazy/needy/emotional, we would be fine.” This shame prevents the borderline from seeking help or support, keeping them trapped.

Breaking Free

Breaking free requires considerable courage and often professional intervention. For the borderline partner, leaving means facing annihilation anxiety. Without the narcissist providing identity scaffolding, they face the self void. Often they say staying in an abusive relationship feels safer “for now” than facing emptiness. One patient explained: “I know he is destroying me, but without him, there is no me to destroy.” It is almost as if their identity is on licence. The work of leaving must include developing alternative sources of identity and learning to tolerate aloneness without annihilation. 684

The practical challenges of dependence are immense. Financial dependence is common, and social isolation means few support systems remain. Self-harm and suicidal ideation often escalate during separation attempts. Many borderlines make multiple attempts to leave before succeeding. 1291

The extinction burst phenomenon makes leaving particularly dangerous. When the borderline finally attempts to leave, the narcissist often experiences narcissistic injury so severe it triggers extreme behaviours including stalking or violence. The period of separation is when these relationships turn most dangerous. 194

Successful separation usually requires intensive therapy and psychiatric support, alongside the slow, painful work of building an identity that never fully formed. 1023

Gender and Diagnosis

Clinicians diagnose BPD predominantly in women, NPD more commonly in men. These patterns reveal as much about our diagnostic systems as about the disorders.

The Feminisation of Borderline Diagnosis

Clinicians diagnose borderline in women at rates of 3:1 over men in clinical settings, though community studies suggest more equal prevalence. 485 The discrepancy points to bias.

Marcus, a 34-year-old electrician from Leeds, describes what his GP called “anger management issues”: “When my girlfriend’s late, I lose it. I’ve put holes in walls. I’ve followed her car. Once I sat outside her work for three hours because she didn’t text back. They sent me to anger management, not therapy. But it’s not anger—it’s terror. I can’t breathe when I think she’s leaving. I’d rather die than be alone.” His presentation—the abandonment panic, the identity that dissolves without a relationship, the desperate controlling behaviours—maps precisely onto BPD. But clinicians diagnose men who cling as borderline; they diagnose men who control with “anger issues” or antisocial traits. Same wound, different expression, different label. 1147

Gendered criteria compound the problem. “Frantic efforts to avoid abandonment” describes behaviours more visible in women. The borderline man who fears abandonment controls instead of clings, drinks instead of cries. Studies show clinicians, given identical vignettes with only gender changed, diagnose BPD more readily in women. Emotional intensity pathologised as borderline in women becomes “typical male anger” in men. 96

Borderline diagnosis descended from hysteria—wandering uteruses, female weakness. The overt misogyny is gone; the structural bias remains. We pathologise emotional intensity and relational focus—behaviours society teaches women—while normalising emotional restriction, which society teaches men. 1336 Sexual trauma, more common in female borderline histories, also contributes: childhood sexual abuse strongly predicts BPD, and the boundary violations map directly onto borderline symptoms. 1360

The Masculinisation of Narcissism

Clinicians diagnose NPD more frequently in men, but underrecognise it in women. The bias runs in reverse.

Male narcissism takes culturally rewarded forms: the tech CEO in his black turtleneck, the billionaire who smokes a joint on a podcast. A man who dominates conversations and demands recognition is an “alpha male,” not a narcissist. Society rewards these traits—the ruthless executive, the arrogant surgeon, the domineering politician—while punishing women for the same behaviours. Successful masculinity and pathological narcissism blur together. 493

Female narcissism hides in different channels. Somatic narcissism manifests as obsession with appearance, constant comparison, excessive cosmetic procedures. Communal narcissism involves being the best mother, the most caring friend, extracting supply through virtue rather than dominance. Vulnerable narcissism declares “I’m special in my suffering” and “No one understands my sensitivity.” Clinicians diagnose these presentations as histrionic or borderline, not narcissistic. 192 989

The same wound—failed authentic recognition—manifests through whatever channels culture provides. Boys encouraged to be special develop grandiose narcissism. Girls taught to derive value from relationships develop communal variants—different masks, same emptiness. 1256

Clinical Implications

For men presenting with “anger issues” or substance abuse, clinicians should probe for abandonment terror and identity diffusion—Marcus’s terror, not his wall-punching, is the diagnostic clue. For women presenting as depressed or anxious, probe for hidden grandiosity: the belief in special suffering, the sense of deserving more than received.

Treatment must accommodate gender. Men with BPD often resist emotion-focused interventions that feel “feminine”; skills training provides a safer entry point. Women with NPD engage better with relational than achievement-focused approaches. And clinicians must address trauma—sexual violence in women, masculine shame in men—alongside personality pathology. The wounds are gendered; treatment must recognise this. 546 76

Treatment Responsiveness

Borderline patients often show significant improvement with appropriate intervention; narcissistic patients remain stubbornly treatment-resistant. Echo can be coaxed from her cave. Narcissus cannot look away from the pool.

The Borderline Treatment Journey

Psychiatry’s transformation from therapeutic nihilism to cautious optimism represents a genuine success story. 953 Long-term studies show that the majority of patients achieve significant improvement or even remission—stunning clinicians and patients alike. This treatability says something fundamental: despite their chaos and suffering, borderline individuals desperately want connection and help.

Dialectical behaviour therapy, developed by Marsha Linehan specifically for BPD, transformed borderline treatment. DBT’s genius lies in its dialectical approach, accepting patients where they are right now, while pushing for change. The skills training modules directly address borderline deficits in emotional regulation and interpersonal effectiveness. Studies consistently show DBT reduces self-harm and hospitalisation while improving overall functioning. 750

DBT’s structure reflects deep understanding of borderline pathology. Individual therapy delivers the relationship borderlines desperately need while maintaining boundaries they must learn. Skills groups teach concrete tools for managing emotions. Consultation teams prevent therapist burnout and keep clinicians from being split. Each component supports the others. 748

Sophie, now 34, describes what DBT gave her: “Before treatment, I’d feel abandoned and immediately spiral—cutting, screaming at whoever was nearest, sometimes ending up in A&E. Now I feel the abandonment wave coming and I have tools. I can name it: ‘This is an emotion, not a fact. Feeling abandoned doesn’t mean I am abandoned.’ I can ride it out. I still feel everything intensely—that hasn’t changed—but I don’t drown in it anymore. For the first time in my life, I have a self that stays the same person whether my boyfriend texts back or not.”

Other approaches work through different doors. Mentalisation-based treatment teaches patients that feelings are mental representations, not facts—that feeling abandoned does not mean being abandoned. Transference-focused psychotherapy uses the therapeutic relationship itself: the borderline’s splitting plays out with the therapist, who becomes alternately saviour and abandoner, and the therapist’s consistent presence despite attacks becomes the corrective experience. Schema therapy provides “limited reparenting,” giving patients within appropriate boundaries what they missed in childhood. 84 251 1351 The approaches differ in technique but share a core insight: the therapeutic relationship is the catalyst for change. The therapist’s consistent presence despite being devalued becomes a corrective emotional experience. 84

Long-term outcome studies provide genuine optimism. The McLean Study tracked borderline patients for over two decades: 85 percent achieved remission within 10 years, though relapses occur. Patients feel better before they function better, but functioning continues improving over time. The chronic, lifelong course once assumed for BPD is myth. Most borderlines improve significantly with treatment and time. 1362 Echo can learn to speak in her own voice. She can find, as Chapter suggested, the relationships that finally say this is who you are, we know you, we remember—the anchors around which a self can crystallise.

The Narcissistic Treatment Challenge

Narcissistic personality disorder stubbornly refuses to budge from the pool. 1050 The very features that define narcissism prevent engagement with treatment. Most narcissists never seek help, and those who do often leave prematurely or show minimal improvement.

Lack of genuine motivation remains the primary obstacle. They simply do not care. Narcissists do not seek therapy to change themselves but to fix others or validate their superiority. One narcissistic elder from an Asian community in Oldham, Manchester explained his therapy goals when forced to attend by his family: “I’m here to understand why everyone else is so incompetent and how to deal with their failures better.” They might seek help during narcissistic crisis—loss of supply or public humiliation—but this crisis-motivated engagement rarely leads to sustained treatment. Once the crisis passes or new supply is found, they just leave.

Therapeutic relationships with narcissistic patients prove frankly brutal. They enter therapy expecting the therapist to admire them and validate that others are the problem. When therapy instead asks them to examine their behaviour, they experience this as narcissistic injury. The therapist becomes devalued: “You’re incompetent,” “You don’t understand me,” “I’ve read more about this than you know.” Maintaining therapeutic alliance requires considerable patience and skill. Some clinicians keep irony journals to survive the experience.

Narcissistic defence mechanisms also actively work against therapeutic progress. Their whole point in life is to protect the false self. When the therapist identifies a problem, grandiose defences immediately activate: “That’s not really a problem,” or “Everyone does that.” When vulnerable feelings emerge, they quickly evaporate into rage or contempt. The very emotions that might motivate change are defended against so mechanically that they never consciously register.

Limited evidence-based treatments for NPD confirm the difficulty. Transference-Focused Psychotherapy, effective for borderline patients, has been adapted for narcissistic presentations but shows almost no success. Mentalisation-Based Treatment struggles as narcissistic patients use cognitive understanding defensively rather than emotionally engaging. Schema therapy approaches narcissistic schemas but encounters powerful resistance. No treatment approaches the efficacy rates seen with borderline interventions. 1051

Different narcissistic subtypes show varying treatment responsiveness. vulnerable narcissists , whose grandiosity hides behind shame, sometimes engage better than grandiose types. Communal narcissists may tolerate group therapy if they can position themselves as helpers. Somatic narcissists occasionally accept treatment for body image concerns, which can secondarily address the underlying narcissism. Understanding subtype can inform treatment approach, though the research confirms that all remain challenging. 993

Successful therapists often show exceptional patience and capacity to tolerate being devalued while seeking the wounded person beneath grandiosity. They must maintain empathy despite extreme provocation. This requires unusual therapeutic stamina and solid self-care. Many excellent therapists simply refuse narcissistic patients, knowing the toll they exact. 1051

Drug treatments do not help. Unlike borderline, where medications can reduce symptoms enough to enable therapy, narcissistic traits show little response to pharmacotherapy. Some clinicians prescribe hoping symptom relief might indirectly facilitate engagement, but evidence is lacking. The narcissistic personality structure remains stubbornly resistant to biological intervention. 1050

Cultural factors enable narcissistic entrenchment. In societies that valorise narcissistic traits—like the West—along with competitive individualism and success at any cost, narcissists see little reason to change. They are often rewarded rather than troubled by their pathology in corporate, military, judicial, and political spheres. One Silicon Valley executive asked why he should develop empathy when lack of empathy made him millions. In cultures emphasising community and interdependence, narcissistic traits will cause more dystonic distress, creating treatment motivation. But globalisation increasingly spreads systemic narcissistic values, centred on lack of empathy, thereby reducing cultural pressure for change. 196

Comparing Narcissus and Echo’s Journeys

Borderline instability, remarkably, enables change. 1362 Fluid identity allows incorporation of new self-concepts—instability makes change inevitable while suffering makes it necessary. Treatment delivers stability and the skills to manage what was chaotic. 405

Narcissistic rigidity prevents change, trapping them and those around them. That false self must be maintained at all costs—giving it up threatens psychological survival as they know it. Treatment asks them to abandon the only self they know without guarantee of replacement. Few take that leap. 993

Age affects these outcomes differently. Borderline symptoms peak in young adulthood and decline with age. The emotional storms of the twenties often mellow by middle age, as life experience teaches some emotion regulation, and the wisdom to spot what is futile. Many borderlines achieve significant natural improvement by their forties. Narcissism, conversely, often intensifies with age as reality increasingly contradicts grandiose fantasies and sources of validation dwindle, forcing the false self to solidify and harden. 951

Insight brings us back to the pool and Narcissus. Borderline patients often have painful awareness of their difficulties. Echo understood her plight. This insight causes suffering but enables engagement with treatment. Narcissistic patients typically lack anything approaching genuine insight. They might intellectually acknowledge certain patterns but do not emotionally own them. “I suppose some people might see me as arrogant” is not the same as “I am arrogant and it damages my relationships.” Without emotional insight, behavioural change remains superficial. 312

The Anxious Sibling

Borderline and narcissistic personalities are siblings from the same traumatic family—sharing attachment wounds but developing opposing adaptations. Echo seeks from others what she cannot provide herself: a voice, an identity, proof of existence. Narcissus constructs a false self that proclaims it needs no one while staring endlessly at its own reflection. Their complementary deficits create powerful mutual attraction and inevitable mutual suffering. Two people drowning cannot save each other.

But Echo’s story need not end in dissolution. The self that never formed can still crystallise—around a therapist’s consistent presence, around relationships that finally provide what was always missing, around the slow discovery that one’s own voice exists and can be heard. The borderline’s very instability, paradoxically, makes change possible. They have no rigid structure to defend. They are looking for anchors—and they can find them.

Narcissus, staring at the pool, cannot look away long enough to find one.