The Dramatic-Emotional Cluster

Dr Séamus Gallagher first met Z in the winter of 2019. She arrived in his NHS consulting room referred by her GP after a suicide attempt that the A&E doctor had called “attention-seeking” in his notes. Gallagher, who had grown up Catholic in County Down during the Troubles, had learned early that attention-seeking and genuine desperation were not mutually exclusive. Sometimes the performance was the only language left.

Z was 28, with a history of intense, unstable relationships and self-harm suggesting Borderline Personality Disorder Borderline Personality Disorder A personality disorder characterized by emotional instability, intense fear of abandonment, unstable relationships, and identity disturbance. Often develops from childhood trauma and shares overlaps with narcissistic abuse effects. . Yet she also displayed grandiose fantasies about golden thrones in heaven, exploited others for admiration, and showed marked empathy deficits characteristic of narcissism. She had forged a car ownership slip to sell a vehicle—fraud, antisocial behaviour—but only when feeling abandoned or empty. Her dramatic emotional displays suggested histrionic features. Did she have one disorder with features of others? Multiple co-morbid disorders? Or did her presentation reveal the artificial nature of our diagnostic boundaries?

Gallagher had transferred three months earlier from a Harley Street clinic to this NHS trust in Greater Manchester. He had trained in Dublin, cut his teeth in the pressure cooker of London private practice, and grown tired of treating wealthy patients whose problems stemmed largely from having too much money and too little purpose. Manchester offered something different: proper medicine, he told his wife: patients who actually needed help. The NHS was haemorrhaging funding that year, mental health services hit hardest. His new caseload was impossible—forty-minute assessments compressed to twenty, six-month waiting lists for therapy that should have started immediately.

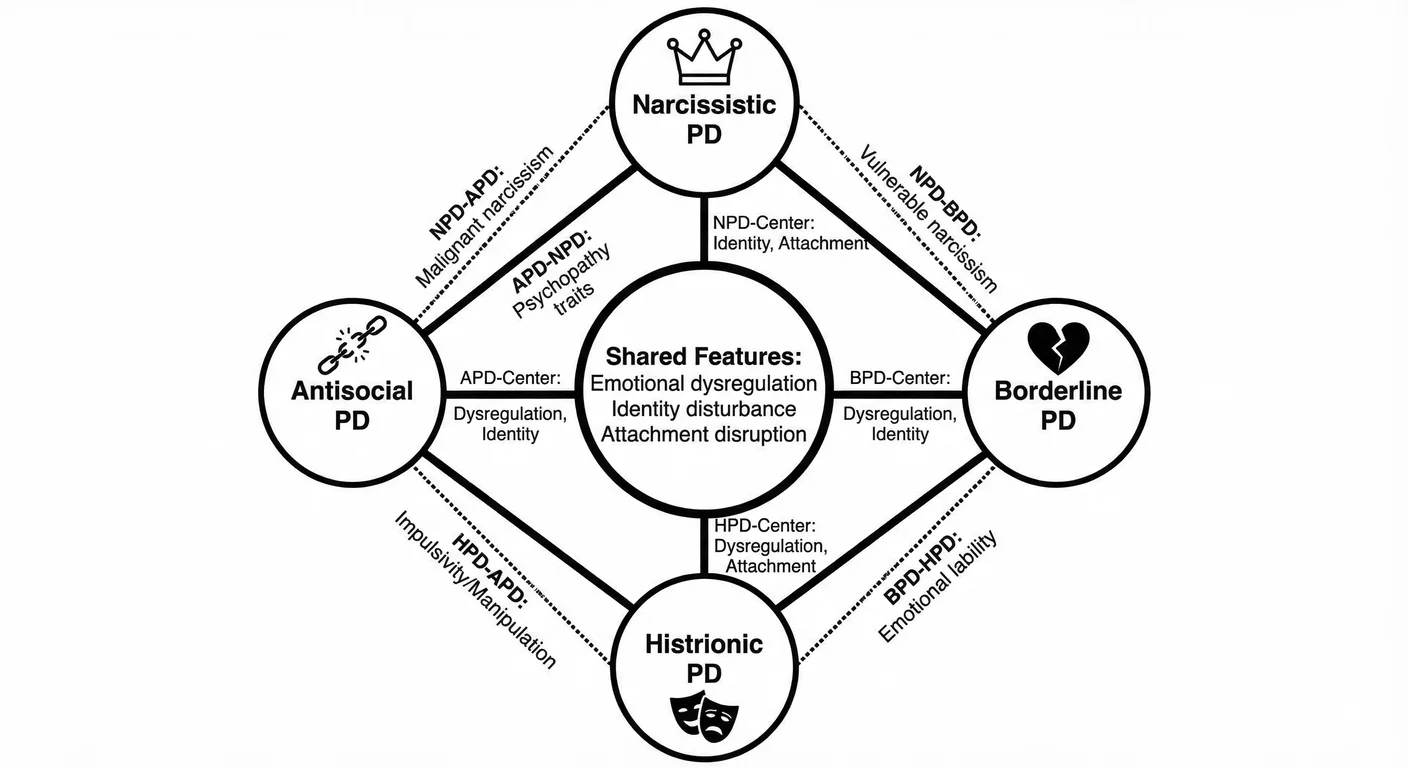

Z’s presentation embodied the diagnostic puzzle at the heart of Cluster B Personality Disorders Cluster B Personality Disorders A group of personality disorders characterised by dramatic, emotional, or erratic behaviour—including narcissistic, borderline, histrionic, and antisocial personalities. —the “dramatic-emotional” cluster that groups four personality disorders together: antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic. 34 These disorders share fundamental disruptions in emotional regulation and identity, yet each expresses its chaos differently. They create interpersonal weather systems: storms of rage and droughts of Empathy Empathy The capacity to understand and share another person's feelings, comprising both cognitive (understanding) and affective (feeling) components—often impaired in narcissism. . Their presence in a room changes the emotional temperature. Understanding how they relate and diverge explains why clinicians like Gallagher so often find themselves uncertain which disorder they are treating.

Clinical observation—not theory—generated this grouping. In the 1980s, factor analytic studies revealed that these four disorder types clustered together statistically, distinct from Cluster C’s anxious-fearful disorders and Cluster A’s odd-eccentric disorders. 101 1259 Empirical grouping preceded theoretical understanding—we still struggle to explain what unites these superficially different conditions.

The “dramatic-emotional” label however, does express something essential about all four. The drama—the borderline’s emotional storms, the narcissist’s grandiose exhibitions—is not the cause but a symptom. It is the chaos an organism makes when it cannot hold a self together on its own. We are beginning to understand that despite mainstream belief, selves do not form in isolation. The research suggests selves crystallise around relationships and particularly around being known and remembered by others. When those anchors are missing or destroyed, the early self appears to fragment, dissolve, or never form—and Cluster B is what the adult results look like.

Medical attitudes towards Cluster B have shifted over the past four decades. Clinicians once dismissed these conditions as untreatable character flaws but they now view them as pathological adaptations to developmental trauma. 951 The stigma remains severe though; mental health professionals often flatly refuse to treat Cluster B patients. They are difficult. Insurance companies often limit their coverage. And the public oscillates between voyeuristic fascination and outright disgust and horror. This stigma affects survivors and those trapped in relationships with Cluster B individuals: it prevents help-seeking and limits both treatment availability and research funding. 735

The gender politics of Cluster B diagnosis warrant scrutiny as well. Clinicians diagnose borderline and histrionic disorders predominantly in women, and antisocial predominantly in men; narcissistic disorder shows only slightly more balance but still skews male. These patterns reflect both genuine gender differences in symptom expression and diagnostic bias. Clinicians have historically labelled women’s anger borderline while viewing men’s anger as socially ‘justified’. They normalise men’s emotional coldness while pathologising women’s. They label sexual behaviour antisocial in men but histrionic in women. These biases affect who gets diagnosed and how we understand these disorders. 95

Cultural context also shapes how narcissism manifests and whether it is recognised as pathology. The DSM criteria were developed primarily in Western ‘individualistic’ societies where self-promotion is more visible and can be identified and stigmatised. In collectivist cultures, narcissistic supply may flow through family status and group achievement rather than individual grandiosity. The Asian executive who insists his family name demands deference, the Middle Eastern patriarch whose honour requires absolute obedience—these may represent culturally shaped narcissism that Western diagnostic criteria miss. Conversely, behaviours normative in individualistic cultures (aggressive self-promotion, personal branding, competitive displays of success) might meet diagnostic thresholds elsewhere. The underlying pathology—fragile self-esteem defended through grandiosity, exploitation of others, empathy deficits—seems to transcend culture but its expression definitely does not. Clinicians working across cultures must distinguish culturally normative self-presentation from pathological narcissism. This is a distinction the DSM acknowledges but does not adequately address. 1048

We do know that developmental patterns predict relational dysfunction. 953 All four typically manifest problems by early adulthood, and we know precursors appear much earlier. Childhood conduct disorder predicts antisocial personality; Emotional Dysregulation Emotional Dysregulation Difficulty managing emotional responses—experiencing emotions as overwhelming, having trouble calming down, or oscillating between emotional flooding and numbing. A core feature of trauma responses and certain personality disorders. predicts borderline features; grandiosity and lack of empathy indicate nascent narcissism.

Unifying Features across Cluster B

While emotional dysregulation underlies all four disorders its expression varies dramatically. 748 The borderline patient experiences emotions as tsunamis that overwhelm all defensive structures. Those with NPD manage their dysregulation through grandiose defences—forever crumbling structures requiring constant reinforcement through Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. . The antisocial personality achieves flatness of affect as a proxy for calm through disconnection from their own and others’ feelings. The histrionic personality amplifies and performs emotions for interpersonal effect in effect bypassing their self as an emotional regulator entirely. Each is a different mask over the same problem: emotions that reveal a lack of self and express true vulnerability. For those around them the cost is living in constant uncertainty—never knowing which version of the person will appear, and tiptoeing around triggers that can shift without warning.

Identity disturbance also pervades the cluster. There is no stable sense of self that anchors healthy relationships. 360 The borderline individual has an unstable, fragmented identity that shifts based on current relationships—whoever they are with determines who they become. The narcissist maintains that rigid False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. which is in itself a paper-thin, brittle construction that must never be questioned. The antisocial personality often shows actual identity poverty: an absence of self masked with predatory drives rather than genuine personality. The histrionic individual performs identity rather than experiencing it, becoming whomsoever will provide maximum attention. In each case, partners and children find themselves relating to a series of strangers wearing some sort of mask, never certain who they married or who truly raised them.

Attachment disruption appears consistently in Cluster B histories as well. 732 Research shows approximately 90 percent of individuals with these disorders have insecure attachment, with disorganised attachment particularly common. This pattern—arising from caregivers who are simultaneously sources of comfort and threat—forges the impossible bind that characterises Cluster B relationships: desperately needing others while being unable to trust them. The result is relationships that feel like psychological hostage situations: partners bound by trauma more than love, and children who cannot leave without guilt nor stay without damage.

Mentalization Mentalization The capacity to understand behavior—in ourselves and others—in terms of underlying mental states like thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions. Narcissists show deficits in this crucial social-emotional skill. deficits—difficulty understanding mental states in self and others—unite the cluster. 401 Early attachment trauma disrupts mentalisation development, leaving individuals unable to distinguish thoughts from reality or their own mental states from others’. They cannot imagine that others have inner lives independent of their own needs. When a partner says “I need space,” they hear abandonment. When a child expresses a different opinion, they perceive betrayal. The projective processes and interpersonal chaos characteristic of Cluster B arise from and maintain these foundational deficits.

Neurobiological abnormalities exist across the whole cluster. 1105 Reduced prefrontal cortex volume appears in all four disorders, most pronounced in antisocial personality. Amygdala hyperactivity characterises borderline and histrionic personalities, while narcissistic and antisocial personalities show amygdala hypoactivity. These patterns suggest that Cluster B disorders represent different outcomes of similar neurobiological vulnerabilities interacting with distinct environmental factors. The brain shapes behaviour; but the behaviour also reshapes the brains of everyone nearby—partners, children, colleagues slowly recalibrated by years of unpredictable exposure.

When Gallagher reviewed Z’s file, he found all five vulnerabilities present, tangled together like Christmas lights pulled from storage. Her emotional dysregulation was unmistakable—she had put her fist through a window during an argument with her mother, then wept for three hours, then laughed about it as though describing someone else’s weekend. Her identity shifted depending on who sat across from her: with Gallagher she presented as an intellectual, quoting Sylvia Plath; her GP’s notes described someone entirely different, girlish and helpless. The attachment history read like a textbook case of disorganisation—a father who left when she was four, a mother who oscillated between smothering devotion and weeks of silent withdrawal.

Z’s mentalisation deficits showed in her bewilderment when Gallagher asked what her mother might have been feeling during those silences. “Feeling? She was not feeling anything. She was punishing me.” The possibility that her mother had her own inner life, her own pain, simply did not exist.

As for neurobiological abnormalities—Gallagher had no scanner in his NHS consulting room, but he had thirty years of clinical intuition, and everything about Z suggested a nervous system wired for threat.

Malignant Narcissists

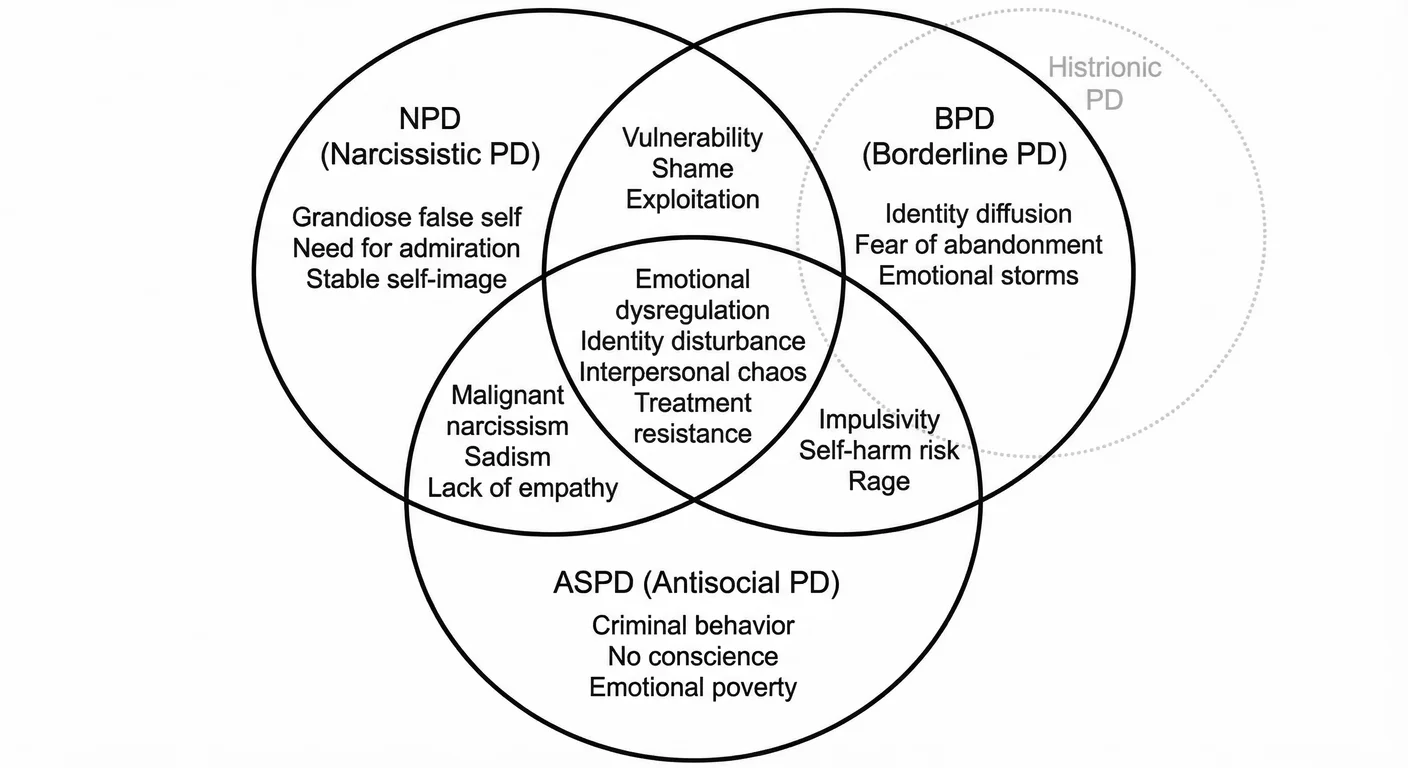

Narcissistic and Antisocial Personality Disorder Antisocial Personality Disorder A personality disorder characterized by persistent disregard for and violation of others' rights, deceit, impulsivity, aggression, and lack of remorse. Part of the Cluster B disorders alongside NPD, with significant overlap in traits. overlap to create something more dangerous than either alone: “ Malignant Narcissism Malignant Narcissism The most severe form of narcissism, combining NPD traits with antisocial behaviour, sadism, and paranoia—representing a dangerous intersection of personality pathology. ”, combining narcissistic grandiosity with antisocial aggression and lack of conscience. 650

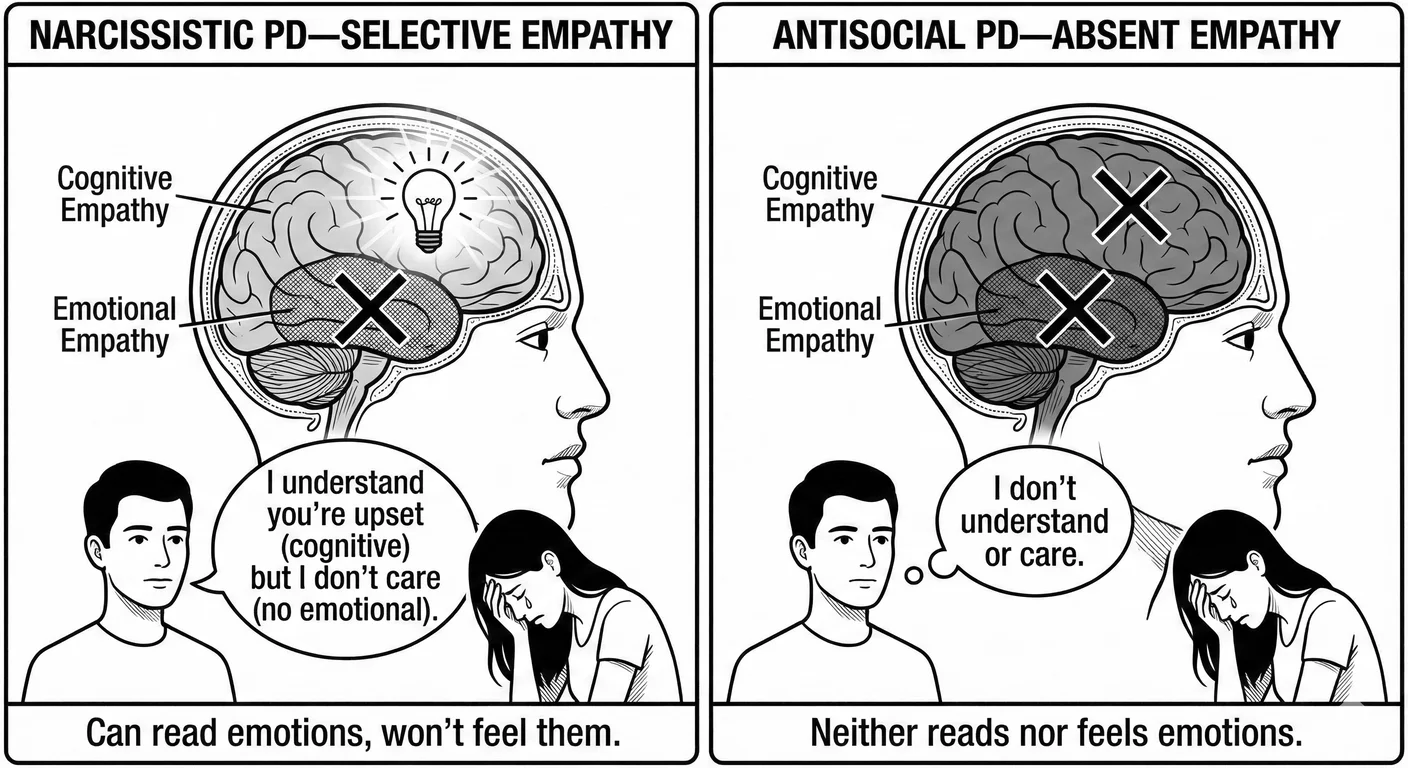

While both involve empathy deficits (as detailed in Chapter 1’s discussion of the nine DSM criteria), the mechanisms differ. 82 Narcissists can understand others’ mental states— Cognitive Empathy Cognitive Empathy The ability to understand another person's perspective and mental state intellectually, without necessarily feeling their emotions. Narcissists often have intact cognitive empathy while lacking emotional empathy. —but do not care about others’ feelings, lacking Emotional Empathy Emotional Empathy The capacity to actually feel what another person is feeling—to share their emotional experience. This is the component of empathy that narcissists characteristically lack. . Emotions are tools to manipulate rather than experiences that enrich and give depth and authenticity to life. Antisocial individuals lack both cognitive and emotional empathy—they neither understand nor care about others’ inner selves or experiences. They are more dangerous in some ways but, due to this shortfall, often less successful at sustained manipulation.

The grandiosity differs qualitatively too; there is a different texture. In NPD, it protects against shame while attracting the attention that maintains the false self. Narcissists need to believe in their superiority. Antisocial grandiosity is just a flat unreasoning belief in one’s entitlement to take what one wants fused with contempt for social rules and those who follow them. They sift the stream of experience for signs of dominance; any other signal from reality threatens their worldview. 649

Exploitation patterns also differ markedly. 649 Narcissists employ Idealization Idealization A psychological defence where someone is perceived as perfect, all-good, and without flaws—the first phase of the narcissistic abuse cycle. - Devaluation Devaluation The phase in narcissistic relationships where the victim is criticised, belittled, and degraded after the initial idealization period ends. cycles, extracting supply while maintaining plausible deniability. It is akin to playing good-cop, bad-cop but with experience. Stretching the person to see what supply will drop out. The cycling itself is an opportunity for extraction. Relationships begin as supply sources and end when depleted. Antisocial exploitation is more immediate. They take without giving due concern for consequences and so do not bother maintaining relationships. By adulthood they have mastered burning their bridges. The narcissist is a parasite; the antisocial a wildfire.

Malignant narcissism fuses the two pathologies into something more dangerous than either. 650 Possessing narcissistic traits such as grandiosity to rationalise any form of exploitation, they add antisocial lack of conscience. This results in them torching successive relationships and creating enemies everywhere. They are charming when supply targets are useful and then flip to ruthless when thwarted. Give them power and sadism emerges.

Serial killers often show malignant narcissistic features. 850 Ted Bundy exemplified the type: grandiose self-perception, belief in his specialness, exploitation of victims for practical and psychological purposes, sadistic pleasure in control. His narcissistic features enabled his crimes. Charm lured victims and his grandiosity convinced him he would never be caught. Entitlement justified murders. His antisocial features drove the criminal behaviour itself. Such individuals seek out the vulnerable and powerless to maximise their sadism, often taking jobs in law, policework, healthcare, and psychiatry. This gives them access to people in crisis, and the power to make them suffer.

Malignant Narcissism Malignant Narcissism The most severe form of narcissism, combining NPD traits with antisocial behaviour, sadism, and paranoia—representing a dangerous intersection of personality pathology. in intimate relationships produces what survivors describe as self death. These individuals do not just devalue partners; they systematically destroy them. Another person’s real self forces a comparison they cannot face. They employ calculated psychological abuse— Intermittent Reinforcement Intermittent Reinforcement An unpredictable pattern of rewards and punishments that creates powerful psychological dependency, making abusive relationships extremely difficult to leave. and isolation that distort reality. The sadistic element means they derive pleasure from their partner’s deterioration. Many survivors report that the perpetrator seemed most alive when causing maximum damage. 42

Divergent Pathways

Narcissistic and antisocial personalities diverge in ways that matter for diagnosis and danger assessment.

Image drives the narcissist; impulse drives the antisocial. 1048 People with NPD carefully guard their false self and will avoid behaviours that might damage their reputation—unless Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. overrides image concerns. The antisocial personality, driven by immediate gratification, engages in obviously self-destructive behaviours that narcissists would avoid. This makes narcissists more dangerous in some ways: their careful image management allows them to maintain positions of power longer, with their social networks constructed and lives maintained in ways that reveal diagnostic clues.

Anxiety separates them further. Narcissists experience significant anxiety about image and supply sources. This ongoing suffering nonetheless provides some behavioural constraint. 849 Antisocial personalities show markedly reduced anxiety; they simply do not care. The narcissist might panic at threatened exposure; the antisocial barely registers such threats. This makes antisocials more likely to engage in criminal behaviour but less likely to maintain elaborate deceptions. They prefer instead to recondition those around them to accept their pathological behaviours as normal. This is why boundary violation observation is so important. Cross the line into threat, exploitation, lying, theft shoud not just be noticed, it should be noted, and responded to immediately. The narcissist will attempt to repair, whether to preserve supply or avoid harm, and the antisocial won’t care but will mumble some excuse until they switch to something more interesting.

Their emotional palettes differ too. Narcissists experience shame. It may be defended against through grandiosity, and alongside envy and longing form a distorted range of emotion, but at least it is a range. 521 Antisocials show genuine emotional poverty: they have less shame, less envy, less of everything except perhaps animal anger. The narcissist’s inner life, while off-key, remains relatively complex; the antisocial’s is fundamentally flat. They tend to compensate by covering themselves in the latest trends, talking points, books, and even colourful clothing. They will divert others from noticing the flatness by giving away little favours or trinkets to encourage recriprocation and engage new supply sources.

Both disorders resist treatment, but narcissists will occasionally engage during crises such as looming divorce, job loss, any potential major Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. . Their need for admiration allows therapeutic leverage if the therapist becomes a valued supply source. Antisocial personalities rarely seek treatment except under legal mandate and show minimal response even then. 654 The narcissist might develop insight without change; the antisocial typically develops neither.

This means developmental trajectories also diverge dramatically. Antisocial personality disorder diagnosis currently requires evidence of conduct disorder before age 15, strongly suggesting early-onset pathology. Narcissistic personality disorder may develop later; sometimes emerging in response to success or trauma during adolescence or early adulthood. 953 Different origins imply different intervention windows—and potentially different causes.

Gallagher ran through these distinctions with Z in mind. Image or impulse? Both—she curated her social media obsessively, yet had keyed that car without a thought for witnesses. Anxiety? Plenty, but about abandonment rather than exposure. Emotional range? Complex, certainly—shame and envy present, longing too, nothing like the flatness of true antisocial pathology.

Treatment responsiveness? She had sought him out, which meant something. And developmental trajectory? No conduct disorder in childhood, according to her mother; the problems had started in adolescence, after the move to Stockport. She did not fit cleanly on either side of the narcissistic-antisocial divide. She sat somewhere else entirely, in territory the textbooks acknowledged but could not quite map.

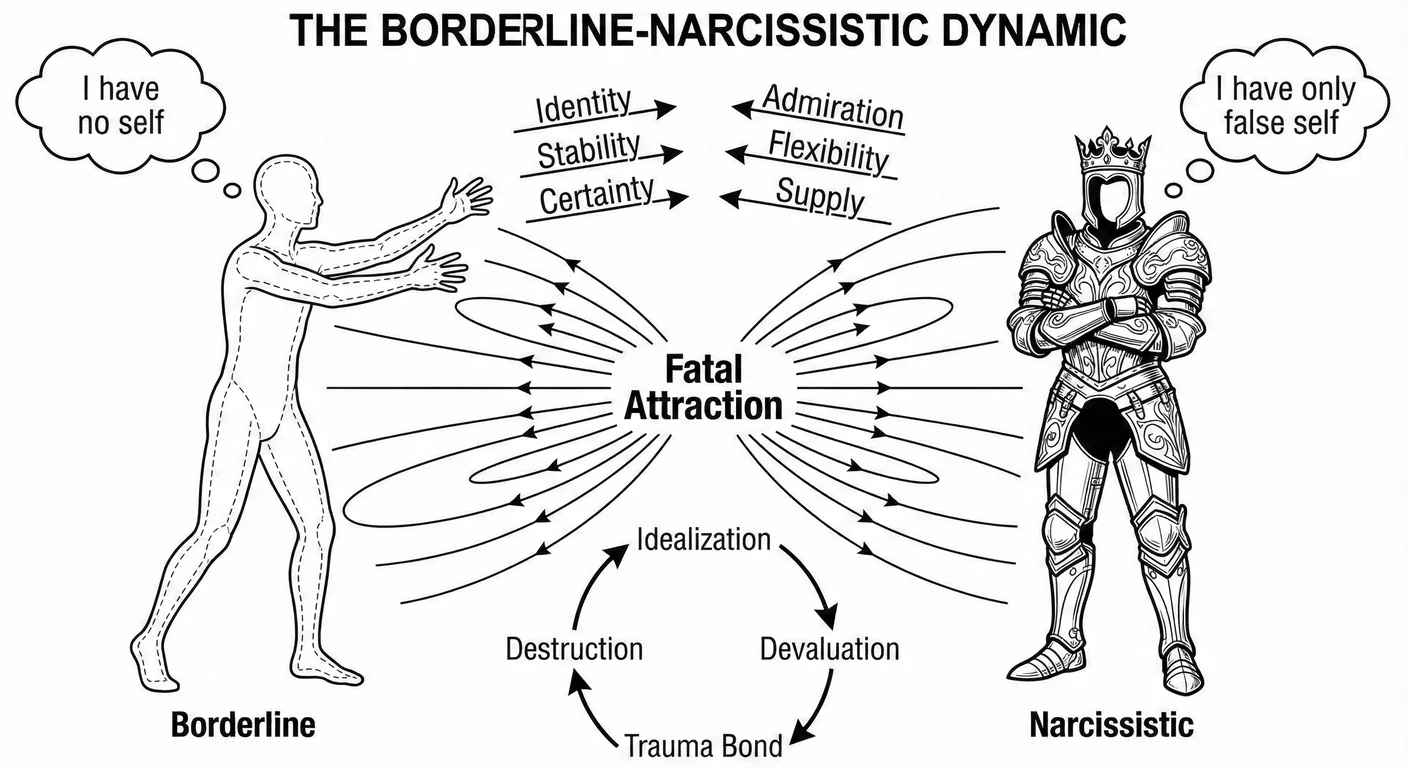

Borderline PD – The Anxious Sibling

Borderline and narcissistic personality disorders form the most dangerous pairing in Cluster B—and the most common. 698 Both share emptiness and identity disturbance, yet manifest them through opposing strategies. The borderline suffers Identity Diffusion Identity Diffusion A poorly integrated or unstable sense of self, characterized by confusion about who you are, what you value, and what you want. Common in personality disorders and in survivors of narcissistic abuse who were never allowed to develop autonomous identities. , a painful awareness of not knowing who they are, while the narcissist denies this through a rigid false self that must never be questioned. One has too little self; the other, too much false self. Both are searching for an anchor.

This complementary pathology creates a powerful mutual attraction. 698 The borderline, lacking stable identity, finds in the narcissist’s grandiose certainty exactly what they desperately need: someone who seems to know who they are. The narcissist finds in the borderline’s identity diffusion perfect Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. —someone who will become whoever the narcissist needs them to be, a mirror that reflects back only what the narcissist wishes to see.

These relationships cycle through intense idealisation and inevitable devaluation, sometimes for decades, creating Trauma Bonding Trauma Bonding A powerful emotional attachment formed between an abuse victim and their abuser through cycles of intermittent abuse and positive reinforcement. so powerful that survivors describe it as addiction. The borderline’s fear of abandonment meets the narcissist’s need for control; each locks the other in place. The next chapter examines this dance in depth—the neurobiological hooks, the cognitive distortions, and why leaving proves so difficult even when staying means destruction. 649

Histrionic PD – The Theatrical Twin

Gallagher had once treated a woman named Cressida who arrived at every session in a different persona: one week the ingenue, breathless and wide-eyed; the next the femme fatale, all knowing glances and provocative sighs; the next the tragic heroine, dabbing at dry eyes with a handkerchief she kept specifically for the purpose. She flirted with Gallagher, then accused him of coldness, then wept at his cruelty, then laughed and said she had only been testing him. Her emotional displays were performances, but she was not faking—she genuinely felt each emotion in the moment, then genuinely felt the next, with no thread connecting them. She did not want Gallagher to admire her brilliance or recognise her superiority. She wanted him to watch her. Any reaction would do. When he maintained therapeutic neutrality, she escalated—threatened to report him, then self-harm, then to seduce his receptionist—not from malice but from desperation. Attention was oxygen. Without it, she felt herself disappearing.

Cressida illustrated the core distinction between histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. Histrionic personality disorder shares so many features with narcissism that some researchers propose it as a female-presenting variant. 870 The debate reveals how gender and clinical bias shape our perception of personality pathology. Both disorders involve performative self-presentation and shallow relationships, using others for self-regulation rather than mutual connection. 34 But histrionic individuals seek attention broadly and indiscriminately—they want to be noticed, and need to be desired, to be exciting to others. The specific content matters less than the attention quantity and intensity. This differs from narcissistic Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. -seeking, which is more selective and hierarchical. The narcissist wants admiration specifically, preferably from high-status sources. Being noticed is not enough; being recognised as superior matters. Cressida wanted Gallagher to watch her; a narcissist would have needed him to be impressed.

The emotional quality is different. 748 Histrionic emotionality is shallow but genuine in the moment—rapidly shifting yet felt. Narcissistic emotional life is more defended and restricted—grandiosity masking emptiness, rage defending against shame. The histrionic individual feels emotions rapidly and superficially; the narcissist avoids feeling vulnerable emotions at all.

Identity organisation distinguishes the disorders. 650 Histrionic identity is impressionistic rather than coherent—vivid moments without connecting narrative. The fit to the acting world is startling. They experience themselves as others experience them, moment to moment. Narcissistic identity, despite emptiness underneath, maintains rigid organisation around the false self. The reactions are mechanised. The false self-concept does not shift based on audience; it demands audience recognition of its pre-existing superiority.

Interpersonal manipulation also differs in style and purpose. 870 Histrionic manipulation achieves immediate attention-getting—dramatic displays designed to draw others in. It is transparent, easily recognised as performance. Narcissistic extraction operates through cycles of idealisation and devaluation designed to maximise supply while maintaining control. Initial charm ( Love Bombing Love Bombing An overwhelming display of attention, affection, and adoration early in a relationship designed to create rapid emotional dependency and attachment. ) hooks the target. Once secured, extraction begins: admiration and resources flowing towards the narcissist. When the source is depleted or resistant, devaluation follows. This is more calculated—though not necessarily conscious—the narcissist has learned these patterns ensure maximum supply with minimum vulnerability.

Relationship patterns are another key area of variety. 105 Histrionic individuals often maintain numerous shallow relationships, each providing different forms of attention. They might have multiple “best friends” who do not know about each other, each believing they are special. These relationships lack depth but provide broad attention sources. Narcissists typically maintain fewer relationships with clearer hierarchies—primary supply sources and potential replacements. Their relationships are more explicitly transactional.

Sexual behaviour patterns distinguish the disorders in style and operation. Histrionic individuals often use sexualised behaviour for non-sexual purposes, dressing provocatively to ensure attention, flirting to create connection, implying availability to maintain interest—the casual “I will date anyone” thrown into conversation. Actual sexual behaviour might be limited or conflicted. Narcissists use sexuality for self-validation and control, notches on bedposts, proof of desirability, power over others. The histrionic individual asks, “Do you want me?” The narcissist states, “You must want me.” 870 40

Three months into treating Z, Gallagher found himself making lists. Borderline features: self-harm and abandonment terror, the way she clung to relationships until she destroyed them. Narcissistic features: grandiose fantasies (she was destined for great things, misunderstood by ordinary people), exploitation of her flatmates for money and emotional labour, blank incomprehension when he asked her to consider their perspective. Antisocial features: the car fraud, yes, but also smaller things—lies that served no purpose, casual cruelty to service workers, the time she described keying an ex-boyfriend’s car with something close to pleasure. And histrionic features: the theatrical distress that evaporated the moment she secured his attention, the way she dressed for sessions as though auditioning for a part, the performative vulnerability that felt both genuine and calculated. He had worked in psychiatry long enough to know that textbook cases existed only in textbooks. But Z was something else. She did not blur the boundaries between disorders; she seemed to occupy all four simultaneously, shifting between them like someone channel surfing through their own personality.

Diagnostic Challenges

Cluster B presentations in clinical practice defy neat diagnostic categories. Z was proof of that—channel surfing through her own personality, as Gallagher had put it to himself. Comorbidity rates between Cluster B disorders range from 40-70 percent, with many individuals meeting criteria for two or three disorders simultaneously. 1370 Are we carving nature at its joints or imposing artificial divisions on inherently dimensional systems?

The Comorbidity Problem

Cluster B disorders refuse to stay in their boxes. Among individuals with narcissistic personality disorder, 40 percent also meet criteria for another Cluster B disorder. Among those with borderline personality, rates are even higher. 485 In psychiatric inpatient settings, 70-80 percent of borderline patients show features of other Cluster B disorders. 1359 These are not rare overlaps but the norm.

When the self is seriously compromised, symptoms proliferate. The diagnostic question—Is the patient borderline with narcissistic features, or narcissistic with borderline features?—often depends on which symptoms are prominent during assessment, which gender the patient presents as, and which theoretical orientation the clinician holds.

Diagnoses prove temporally unstable too. The rebellious adolescent with conduct disorder becomes the young adult with antisocial personality, who “mellows” into middle-aged narcissism. The dramatic young woman diagnosed histrionic develops more stable narcissistic features with age. Are these different disorders or developmental variations of common underlying pathology? 951

Assessment itself compounds the confusion. 1048 Cluster B individuals present differently depending on context and psychological state. The narcissist in crisis appears borderline. The borderline in a stable period seems merely histrionic. The antisocial facing legal consequences strategically presents as traumatised and vulnerable. Single-session assessments capture snapshots, not portraits.

A consultant psychiatrist in Leeds described inheriting a patient from three previous clinicians. The first had diagnosed borderline personality disorder after witnessing emotional storms and self-harm. The second, seeing the patient during a stable period, revised to narcissistic personality disorder—the grandiosity and contempt were unmistakable. The third, reviewing the criminal record, settled on antisocial personality disorder. “When I met her,” the consultant said, “she was charming, seductive, and kept mentioning her connections to important people. I thought: histrionic, obviously. Then I read all three previous assessments and realised we had each met a different person. Or rather, we had each met the same person in a different state, and diagnosed accordingly.” The patient had not changed. The diagnostic categories had simply failed to capture someone whose pathology shifted faster than the assessment process could follow.

Differential diagnosis

Challenges

Surface behaviours may look identical while serving different psychological functions—distinguishing between Cluster B disorders requires careful attention to motivation and developmental history. 654 Get the diagnosis wrong and the treatment fails—or worse, causes harm. Clinicians know this, which is one reason many refuse to engage. The diagnosis may change with revelations, and Cluster B patients may weaponise the update to prove their clinician is inept.

Gallagher ran through the differential with Z, and each possibility carried a different cost if wrong.

If he diagnosed borderline and missed the narcissism, he might validate her victimhood narrative while she continued exploiting her flatmates—the treatment would address her abandonment terror while ignoring the damage she inflicted on others.

If he diagnosed narcissistic and missed the borderline, he might challenge her grandiosity while she escalated to genuine self-harm—the treatment would confront her entitlement while missing the suicidal desperation underneath.

If he emphasised the antisocial features, he might write her off as untreatable and discharge her to a system that would eventually find her dead or imprisoned—the diagnosis would be defensible but the patient would be lost.

If he focused on the histrionic presentation, he might dismiss her distress as performance and miss the genuine suffering—the treatment would address the theatre while ignoring the terror driving it.

Each diagnostic lens revealed something true and obscured something essential. The stakes were not academic. Get it wrong, and Z would either harm herself or harm others—or both, in the particular pattern that Cluster B so often produces.

Self-harm illustrates the complexity. The borderline hurts themselves to regulate unbearable emotions—physical pain distracts from psychic pain. The histrionic does so for dramatic effect, ensuring others see the wounds. The narcissist self-harms during collapse, attacking the body that failed to maintain perfection. The antisocial does so to demonstrate toughness or to manipulate systems. The behaviour is identical; the meaning, entirely different. 649

Interpersonal patterns provide the most immediate diagnostic clues. Borderline relationships show approach-avoidance conflicts—desperate clinging alternating with angry withdrawal. Narcissistic relationships follow idealisation-devaluation-discard cycles. Antisocial relationships are purely instrumental—others exist as objects to manipulate and then discard. Histrionic relationships are numerous but shallow. The quality of relational dysfunction points towards specific diagnoses, often visible through basic review of emails and messaging patterns. 105

Mixed Presentations

Most patients do not fit neatly into one box. Two combinations appear most frequently.

The “borderline-narcissistic” combination involves alternating between borderline vulnerability and narcissistic grandiosity. During attachment threat, borderline features dominate: clinging, self-harm, identity confusion. When stabilised, narcissistic defences emerge (devaluation and entitlement). Therapists describe feeling whipsawed between a desperate child and contemptuous adult; interventions appropriate for one state may be harmful in another. 651

The “antisocial-narcissist” represents malignant narcissism discussed earlier: grandiosity combined with aggression, exploitation without restraint. These individuals use narcissistic charm to enable antisocial exploitation, maintaining enough image management to avoid consequences while engaging in predatory behaviour. Corporate fraudsters and domestic abusers often show this pattern. 650

When early trauma is severe enough, individuals may show features of all four Cluster B disorders—what clinicians call “pan-cluster B” presentations. The damage was so early and pervasive that different symptoms emerge based on context: borderline in intimate relationships, narcissistic at work, antisocial under stress. Z was one of these. Treatment cannot address one disorder while ignoring others; everything must be worked on at once. 724

“Pan-cluster B.” Gallagher circled the term in the journal article he was reading one evening, long after Z had left his consulting room in tears—or what had looked like tears until he noticed her checking her reflection in his window.

The phrase captured something, but it also felt like a surrender. What did it mean to say someone had features of everything? That the categories were useless? That the damage was so severe it had shattered the person into diagnostic fragments?

He thought about the multidisciplinary meeting scheduled for the following week, where he would present Z’s case to colleagues who would each see her through the lens of their own speciality. The psychologist would focus on her attachment history. The social worker would emphasise her housing instability and benefit struggles. The psychiatrist would wonder about medication. The nurse would note her weight loss. Each perspective was necessary; none was sufficient.

Gallagher had learned in his training that diagnosis should guide treatment, but with Z the diagnosis seemed to shift depending on which treatment you wanted to try. He was beginning to suspect that the real question was not which disorder she had, but whether the very concept of discrete disorders could survive contact with someone this broken.

He was not alone in that suspicion. The debate between dimensional and categorical approaches to personality disorders has intensified as comorbidity rates have climbed. 1323 Categories offer clarity—patients in crisis need immediate answers, not continuums. But dimensions better capture reality: personality pathology is continuous, which explains why so many patients meet criteria for multiple disorders. The trade-off is real. Dimensional approaches risk reducing people to data points, yet escape labels like “grandiose” or “antisocial” that stigmatise more than they illuminate.

Culture and Context

No pathology exists in isolation. The narcissistic executive shapes corporate culture; corporate culture then attracts and promotes narcissistic executives. A hothouse emerges. The borderline patient’s Splitting Splitting A psychological defence mechanism involving all-or-nothing thinking where people or situations are seen as entirely good or entirely bad, with no middle ground. reflects family dynamics; family dynamics reproduce the splitting. Antisocial exploitation flourishes where systems reward predation. Histrionic attention-seeking intensifies in cultures obsessed with visibility. Individual disorder and social context feed each other in loops that are easier to enter than escape.

Understanding Cluster B dynamics helps us identify toxic organisational cultures and political polarisation—ideally before one is drawn into them. 1252 When narcissistic leaders create organisational cultures rewarding Cluster B traits, they attract and promote similar individuals while driving out healthier personalities. Social media algorithms reward engagement, selecting for Cluster B content: the controversial and polarising posts that generate maximum reaction.

The Western Bias Problem

A psychiatrist trained in Mumbai described her first months working in an NHS trust. “I kept seeing patients who, by the DSM, met criteria for borderline personality disorder—the identity instability, the shifting sense of self depending on who they were with. Then I realised: in the culture I came from, that flexibility was not pathology. It was how you survived in a world where family came first and individual identity was almost a Western luxury.” She learned to ask different questions: not “Who are you?” but “Who are you in relation to?” The answers often made the diagnosis evaporate—or revealed something the Western framework could not name.

These diagnostic categories emerged from studies of predominantly Western, middle-class patients in North American and European clinical settings, then were broadcast globally as universal truths. Critics characterise the DSM as resting upon an “undeclared ethnocentrism,” using Western cultural norms as a tacit measure. 667 The ICD, while more internationally developed, still reflects primarily Western conceptualisations of selfhood and pathology. Serious questions emerge: are we identifying universal human pathology or culturally specific patterns mistaken for universal disorders?

Collectivist cultures conceptualise personality differently. 734 In Japan, taijin kyofusho—fear of offending others through one’s appearance or behaviour—embodies a culture-specific pattern that simply does not map onto Western categories. What might be labelled “avoidant” in Western contexts could be culturally syntonic social anxiety in Japanese contexts. The social self there has genuinely different parameters and operates differently. Similarly, ataque de nervios in Latin American cultures involves dramatic emotional displays that might be misdiagnosed as histrionic or borderline by clinicians unfamiliar with cultural idioms of distress.

Western individualism underlies the self-concept in Cluster B diagnoses. 667 The “stable, integrated identity” considered healthy in Western psychology can be pathological in cultures valuing contextual flexibility and interdependence. In many African cultures, identity is fundamentally relational: “I am because we are” (Ubuntu philosophy). The Western emphasis on individual identity consolidation as mental health comes from cultures representing a small fraction of the human population, and risks pathologising healthy interdependence. A Vietnamese patient whose identity shifts based on family context is not necessarily borderline; they might be displaying culturally appropriate relational flexibility.

Indigenous trauma responses often get misread as personality pathology. 472 Historical trauma from colonisation and systematic oppression creates intergenerational patterns that superficially resemble Cluster B features: identity disruption from cultural destruction and emotional dysregulation from unprocessed collective trauma passed down through generations. Diagnosing these as individual personality disorders obscures their sociopolitical origins and perpetuates harm.

Clinicians must develop cultural formulation skills to avoid misdiagnosis. 11 This involves understanding how culture shapes emotional expression and identity formation. A Middle Eastern woman’s emotional intensity often reflects cultural norms, not borderline pathology. An East Asian man’s apparent lack of emotional expression often indicates cultural stoicism, not antisocial flatness. Extended family dynamics also amplify and consolidate these differences, creating collective patterns whose interactions clinicians are only beginning to recognise.

It was Z’s grandmother who finally unlocked something. Six months into treatment, Z mentioned offhandedly that her nan was Pakistani, had come to Bradford in the 1960s as a young bride, had raised seven children in a two-bedroom terrace while her husband worked double shifts at the mill. Gallagher asked about the extended family, and for the first time Z’s brittle performance softened into something that looked like genuine feeling.

She described Eid gatherings with thirty cousins, her grandmother’s house as the axis around which an entire community rotated, the aunties who had fed her and scolded her and known her since birth. “But we moved,” Z said. “My mum wanted out. She married an English bloke, we went to Stockport, and then he left and we had nobody.” The abandonment that structured Z’s psychology was not merely personal; it was cultural, a severance from a world where identity was collective and family was fate.

Gallagher thought of his own childhood in Bangor, the suffocating closeness of the parish, the way everyone knew your business and your grandparents’ business and formed opinions accordingly. He had fled that world for Dublin, then London, then—ironically—back north.

He understood the pull of escape, the seduction of reinvention. But he also knew what was lost when the old ties were cut. Z’s mother had sought freedom and found isolation; Z had inherited the isolation without understanding its origins. In a culture that worshipped individual autonomy, this looked like pathology. In the context of her grandmother’s Bradford, it might have looked like grief.

Hope and Healing

Evidence for Recovery

Long-term follow-up studies show prognosis better than clinicians once believed: many individuals achieve significant improvement or remission. The McLean Study of Adult Development found that 93% of borderline patients achieved remission (no longer meeting diagnostic criteria) lasting at least 2 years over 16 years of follow-up, though 30% experienced recurrence. 1362

“Good-enough outcome” has changed expectations for Cluster B treatment. Rather than requiring complete personality restructuring, clinicians now focus on achievable goals: reducing self-harm and stabilising relationships while developing Mentalization Mentalization The capacity to understand behavior—in ourselves and others—in terms of underlying mental states like thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions. Narcissists show deficits in this crucial social-emotional skill. capacity. A formerly chaotic borderline patient who achieves stable housing, even if still emotionally sensitive, represents therapeutic success. A narcissistic individual who develops sufficient empathy to maintain family relationships, despite residual grandiosity, has improved. 403

Neuroplasticity research offers particular hope. Brain imaging studies of borderline patients completing Dialectical Behaviour Therapy show measurable changes in prefrontal cortex volume and amygdala reactivity after one year of treatment. 476 The amygdala—that hyperactive alarm system firing at every perceived slight—quiets. The prefrontal cortex—the brake that should modulate emotional reactions—strengthens. These are not metaphors. They are visible on scans, measurable in millimetres of grey matter, correlating with the patient’s lived experience of feeling less overwhelmed, less reactive, more capable of pausing before the storm hits.

A DBT therapist in Edinburgh described watching this transformation unfold. “In her first year, my patient would spiral for days after a perceived rejection—a friend not texting back, a look from a colleague. By year three, she could notice the feeling rising, name it, and choose not to act on it. The feeling was still there. But she was no longer its hostage.” Similar neuroplastic changes occur with transference-focused psychotherapy and mentalisation-based treatment. 799 The “broken brains” narrative is wrong. These are neuroplastic conditions. The right treatment changes the brain.

Recovery narratives challenge therapeutic nihilism. 1274 Published accounts describe journeys from severe personality pathology to meaningful recovery, often emphasising that while traits may persist, their impact can be dramatically reduced. These narratives consistently identify key factors: finding therapists who balance validation with accountability and gradually building authentic relationships that do not replicate early trauma patterns.

The Hidden Victims

Family members and partners of Cluster B individuals often suffer trauma that goes unrecognised. Studies indicate that 30-40% of family members meet criteria for PTSD; partners show elevated rates of depression and complex trauma. 62 These hidden victims require support that acknowledges two truths simultaneously: the Cluster B individual’s behaviour stems from genuine pathology, yet this does not excuse harm caused. Both things are true. Both must be held.

Children of Cluster B parents face particular challenges. They grow up without the stable mirroring that forms identity, often becoming invisible as parental drama consumes all available attention. Some become caretakers; others become extensions of the parent’s needs; still others are cast as villains in a narrative they never chose. The wounds show up decades later, in their own relationships, their own parenting, their own fragile sense of self. 1272

Post-separation often brings escalation rather than relief. Narcissistic and antisocial individuals may weaponise children, legal systems, and social networks. Safety planning must account for personality pathology—the ordinary assumptions about co-parenting and moving on do not apply. 1172

What Remains

Gallagher treated Z for eighteen months before she moved to Birmingham for a job—a real job, in marketing, secured through an employment support programme his trust had somehow preserved through the funding cuts. On her final session, she brought him a card with a handwritten note: “Thank you for not giving up.” He kept it in his desk drawer, not because the treatment had been a success in any conventional sense, but because it reminded him of something important. Z still met criteria for borderline personality disorder on her discharge assessment. Her narcissistic features remained, though less florid; she had developed enough insight to catch herself mid-exploitation and occasionally choose differently. The antisocial behaviours had diminished—no new frauds, no new property damage—though Gallagher suspected this owed as much to stable housing and regular income as to therapeutic intervention. Her histrionic presentation softened when she no longer needed drama to secure attention.

Had he cured her? No. Had the diagnostic categories helped him treat her? Not particularly. What had helped, in the end, was something simpler: sustained attention from someone who refused to be either seduced or repelled. She had tested him constantly—idealising him one week, accusing him of incompetence the next, missing sessions, overdosing, showing up at A&E at 3 a.m. demanding he be called. He had held the frame, as his supervisor would say. He had remained interested in her without being consumed by her. For someone whose early attachments had oscillated between smothering and abandonment, this was genuinely new information about what relationships could be.

The visit to Bradford had been the turning point, though not in any way the textbooks would recognise. Z had reconnected with her grandmother, tentatively at first—a phone call, then a visit, then a regular Sunday lunch that she reported with something like wonder. “She is old now,” Z said. “She does not remember everything. But she remembers me. She calls me by my real name.” Gallagher never learned what that name was. But he watched Z’s identity stabilise around it, as though the grandmother’s memory was a mooring line thrown across forty years of drift.

The Cluster B constellation defies neat resolution. The categories blur into each other; the patients slip between diagnostic criteria; the treatments work partially and never permanently. What remains constant is the underlying wound: a self that never found its anchor, never had someone say this is who you are, I know you, I remember. Z found hers in Bradford, in a grandmother’s fading memory, in a name Gallagher never learned. Not everyone is so lucky. But the possibility exists—the self can still crystallise, even late, around relationships that finally provide what was always missing. Narcissus staring at his reflection, Echo reduced to repetition, and all their modern descendants trying to construct identities from whatever materials come to hand. Sometimes the materials arrive. The next chapter examines the closest of narcissism’s siblings—borderline personality disorder—and the dance that occurs when these two wounded souls find each other.