The Myth as Mirror

The pitch may have been flawless, but the empathy was missing. A Silicon Valley entrepreneur stood before a room of investors, presenting his revolutionary app that would “democratise personal branding.” Artificial intelligence would ensure maximum engagement. “Everyone deserves to be seen as extraordinary,” he proclaimed, his own image multiplied across the conference room’s screens: LinkedIn profile, Instagram feed, TED talk screenshot, Forbes 30 Under 30 mention. After the pitch, instead of applause, silence—textured and pregnant. When, finally, an investor asked about the societal implications of further amplifying self-promotion, the entrepreneur seemed genuinely puzzled. “But isn’t that what everyone wants?” he asked. “To be admired?”

He is not an outlier. He is a symptom of something measurable, which has been accelerating for decades. A study of fourteen thousand American college students between 1979 and 2009 revealed something disturbing: today’s students score 40% lower on measures of empathic concern and perspective-taking than students of the late 1970s and early 1980s. 679

The decline accelerated dramatically after 2000 (one barely needs to mention 9/11 and the shift in global attitudes that followed). 679 Students can still perspective-take, meaning they can see things from another’s point of view, but their motivation to do so has withered. The same demographic showing empathy decline also showed corresponding increases in narcissistic traits. 1251 This relationship suggests more than coincidence: narcissism appears to directly inhibit empathic development.

The entrepreneur pitching his wares would have been recognisable to observers even in the ancient world. The Greeks grappled with the same human tendency and encoded their understanding in myth.

Around the turn of the common era, the poet Ovid captured this same fatal confusion in his classic “Metamorphoses,” penning the tale that would give us our most enduring metaphor for pathological self-love. The story of Narcissus appears simple but conceals depths: a beautiful youth falls in love with his own reflection and wastes away, unable to tear himself from his own image. This brief parable encodes wisdom about self-obsession that modern psychology is only now beginning to unfold.

The Original Narcissus

Ovid’s version begins not with Narcissus but with his conception, itself a heart-wrenching story of violation and prophecy. His mother, Liriope, a river nymph, was enveloped by the river god Cephissus in his waters. When Narcissus was born, blessed with extraordinary beauty and a divine lineage, Liriope consulted the blind prophet Tiresias about her son’s future. Would he live to old age? Tiresias gave his cryptic answer: “Yes, if he never knows himself.”

This prophecy immediately inverts the Greek philosophical tradition’s highest command: “know thyself,” inscribed at the temple of Apollo at Delphi. The paradox is intentional and significant. Self-knowledge, the Greeks understood, meant grasping one’s limitations as a mortal and so accepting one’s dependence on others and the divine. What Narcissus would discover was something else entirely: self-obsession masquerading as self-knowledge, an infatuation dressed as understanding.

He grows to sixteen, desired by many but touching none. Ovid tells us he possessed “pride so unyielding” that no suitor could reach him. Enter Echo, the wood nymph cursed by Juno to repeat only the last words spoken to her. Echo’s disability transforms into a powerful metaphor: she represents all those who lose their own voice in relationship with a narcissist, reduced to merely reflecting back what the self-absorbed other wants to hear.

Echo follows Narcissus through the forest, burning with love but unable to speak first. When Narcissus, separated from his hunting companions, calls out ‘Is anyone here?’ Echo can only respond ‘Here!’ Their tragic dialogue continues: ‘Come!’ calls Narcissus. ‘Come!’ Echo replies, relieved, emerging from her hiding place with arms outstretched. ‘Hands off!’ Narcissus recoils. ‘May I die before you have me!’ ‘Have me!’ Echo pathetically repeats.

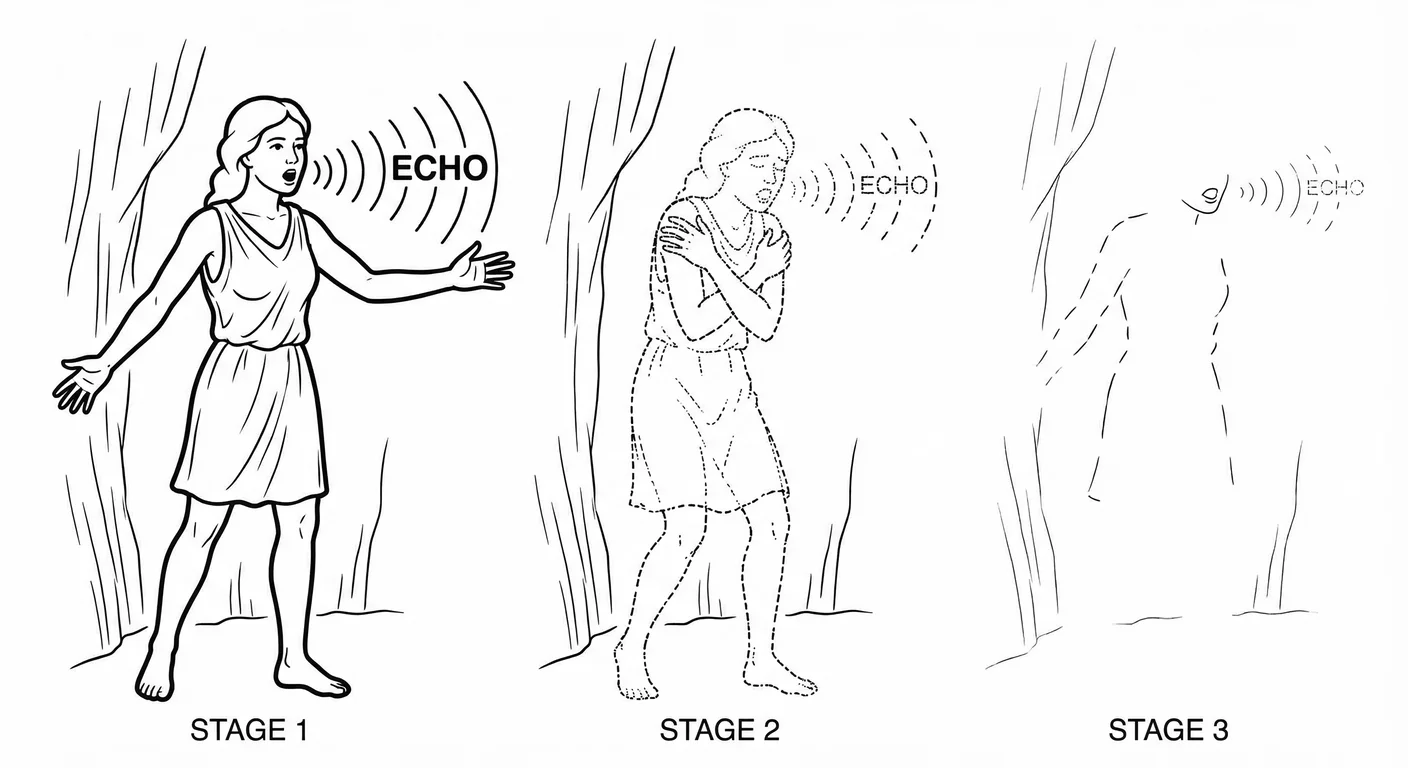

Rejected and humiliated, Echo retreats to caves and lonely places, her body wasting away until only her voice remains. Reduced to a disembodied presence, she haunts these empty spaces. Her fate prefigures what psychologists now recognise in those who love narcissists: the self erodes systematically, one’s own voice gradually disappearing until nothing remains. 42 338 Selves crystallise around relationships that say this is who you are, I know you, I remember. Echo had no such anchor. She could only repeat what others said; there was no one to reflect her back to herself.

The gods, witnessing this cruelty, ensure Narcissus experiences the pain he inflicted. One day, exhausted from hunting, he discovers a pool of water “silver with shining waters” untouched by shepherds or beasts—a perfect mirror. As he bends to drink, he sees his reflection and immediately becomes enthralled. Ovid’s description is clinically precise: Narcissus does not initially realise he is seeing himself. He falls in love with what he believes is another person, a water spirit perhaps, of incomparable beauty.

This is not merely self-admiration. The narcissist loves an idealised False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. , loving it precisely because they cannot develop or access their real self. 649

The recognition scene, when it comes, is devastating in its psychological accuracy. Narcissus realises the beautiful face moves when he moves, smiles when he smiles. ‘But it is I!’ he cries. ‘I know it now. My image does not deceive me. I burn with love of myself. I move and am moved by my own fire’. Even this recognition cannot break the spell. If anything, it intensifies his torment. He knows the image is himself, knows it cannot satisfy him, yet remains paralysed by the addiction to his own reflection.

Pathological narcissism persists even in the face of awareness. Modern neuroscience confirms this, showing that narcissistic personality disorder involves neurological patterns that maintain themselves despite conscious recognition of their destructiveness. 1037 82 These individuals sometimes achieve moments of clarity, even understand intellectually their patterns of behaviour, yet remain locked in cycles of self-inflation and interpersonal exploitation.

Narcissus wastes away by the pool. Neither eating nor sleeping, he is sustained only by his fixation. Tearing himself away, he always turns back. His last words (‘Alas!’) are echoed by Echo, still faithfully reflecting despite her own annihilation. When he dies, even in the underworld, he continues staring at his reflection in the River Styx, unable to join the rest of humanity in their accorded places. In his place, beside the pool, grows the Narcissus flower, nodding at its own image in water—nature’s reminder that some patterns are so fundamental they transcend even death.

What the Greeks Knew

The Narcissus myth crystallised centuries of Greek thought about what they called hubris—the refusal to recognise human limits. 317

Hubris was not simply arrogance; it was a fundamental violation of the cosmic order, a failure to recognise one’s place in the hierarchy of gods and humanity. The hubristic individual claimed more than their portion, whether of honour or, in Narcissus’s case, desirability. They positioned themselves as exempt from the reciprocal obligations and empathy that bound society together.

The Delphic maxim “know thyself” exemplified the antithesis of Narcissus’s fate. This was a warning from the Gods to know mortal human limitations: know that you are mortal and fallible. The ideal was sophrosyne—moderation and wisdom about one’s place in the cosmos, an understanding that one’s place in this causal web of relationships must be mutually empathic and reciprocal. Narcissus violated these principles by placing himself above human relationships.

Greek philosophy emphasised the fundamentally social nature of human identity. Aristotle argued that humans are “political animals” who achieve their nature only through community. 712 Identity, in this view, forms through anchoring relationships—others who know us, remember us, reflect us back to ourselves. The isolated individual, cut off from such bonds by choice rather than circumstance, was either beast or god—certainly not fully human. Narcissus’s rejection of Echo and all other suitors embodied this denial: without anchors, the self cannot cohere.

From Myth to Medicine

Two millennia passed before psychology began naming what the Greeks already knew.

The Birth of a Diagnosis

In a Victorian-era consulting room, a patient confessed to spending hours admiring himself in mirrors, experiencing physical arousal from his own image—the Narcissus myth made flesh. Havelock Ellis, documenting this case in 1898, became the first to apply the ancient name to a modern diagnosis. 357 Freud later transformed it from a clinical curiosity into a psychological cornerstone. His 1914 paper reframed narcissism away from perversion towards a necessary developmental stage— primary narcissism . This was the infant’s self-love before they distinguish self from other. 419 When adults regress to this state after injuries to self-esteem, Freud called it secondary narcissism : their libido withdrawn from the world and redirected to the self.

He introduced the idea of Ego Ideal Ego Ideal A psychoanalytic concept referring to the internalized image of who we should be—our ideal self formed from parental expectations, values, and aspirations. In narcissism, the ego ideal is often grandiose and serves as a defense against feelings of inadequacy. : an internalised image of perfection against which the actual self is measured. 419 When the gap between ideal and reality becomes unbearable, individuals retreat into narcissistic fantasy rather than face their limitations. This insight foreshadows our later understanding of the False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. —and the shame it exists to hide.

From Self-Love to Fractured Self

By the 1960s, clinicians had discovered something new: Freud’s framework could not explain it. These patients did not actually love themselves. They oscillated violently between fantasising they were godlike and fearing they were nothing. 649 Otto Kernberg, a psychoanalyst who had fled Nazi-occupied Austria as a child, saw in his patients a familiar pattern: the desperate construction of a false world to survive an unbearable real one. They had failed to integrate positive and negative representations of self which left them flickering between grandiosity and terrifying emptiness. His concept of “malignant narcissism”—narcissism fused with sadism—would later be applied to everyone from serial killers to dictators. 650

Heinz Kohut was working in Chicago with patients whose suffering seemed less about conflict than about absence. This offered a different clinical lens: not centred around conflict but arrest. 674 676 The grandiosity, he thought, was a legacy artefact; a cry for help by an infant self that had been stunted and unable to mature. “ Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. ”—wounds to pride inciting rage or withdrawal became a central focus. Narcissists seemed to require constant mirroring to maintain their fragile self-image; when that supply was threatened, they responded with explosive anger or crushing depression.

Narcissistic personality disorder entered the psychiatric canon in 1980. 33 The current diagnostic bible known as the DSM-5-TR maintains nine diagnostic criteria while recognising what clinicians have long observed: not all narcissists are loud braggarts. The Covert Narcissism Covert Narcissism A subtype of narcissism characterised by hidden grandiosity, hypersensitivity, chronic victimhood, and passive-aggressive manipulation rather than overt arrogance. subtype—individuals harbouring grandiose fantasies while presenting as inhibited or victimised—now has formal recognition. The wounded martyr and the preening executive share more in common than either would admit.

Portrait of a Narcissist

What does pathological narcissism actually look like in the world? Not the caricature of preening vanity, but the lived reality—for the narcissist and those caught in their orbit.

It begins with our modern word for hubris: grandiosity—not a healthy confidence or even arrogance, but a reality where one’s importance is axiomatic, cosmically ordained. We see this in the patient genuinely baffled at having to wait for an appointment, or the executive who bankrupts a company but lectures the board on their visionary genius. This grandiosity shields against shame while justifying exploitation of others who are, by definition, less important. Children of such parents grow up believing their own achievements will never matter. Partners find their successes minimised, and their struggles dismissed as trivial.

Grandiosity feeds on fantasy—not ordinary daydreams but consuming alternative realities. The struggling artist inhabits a world where museums compete for their work, dismissing actual unemployment as temporary, corrupted, blind to brilliance. Those closest get conscripted: partners must play adoring audience to greatness that never materialises. Children must perform as dynasty extensions. Employees who fail to share the “vision” become saboteurs.

With such fantasy comes a conviction of specialness. Normal rules simply do not apply. In therapy, such patients insist they need a specialist, someone who has worked with “gifted individuals.” They name-drop constantly, establishing position in an imagined hierarchy. Children learn that being ordinary is shameful—they are either exceptional or they were always nothing. Partners who fail to reflect sufficient status are criticised or replaced. Friends are selected and discarded based on prestige value.

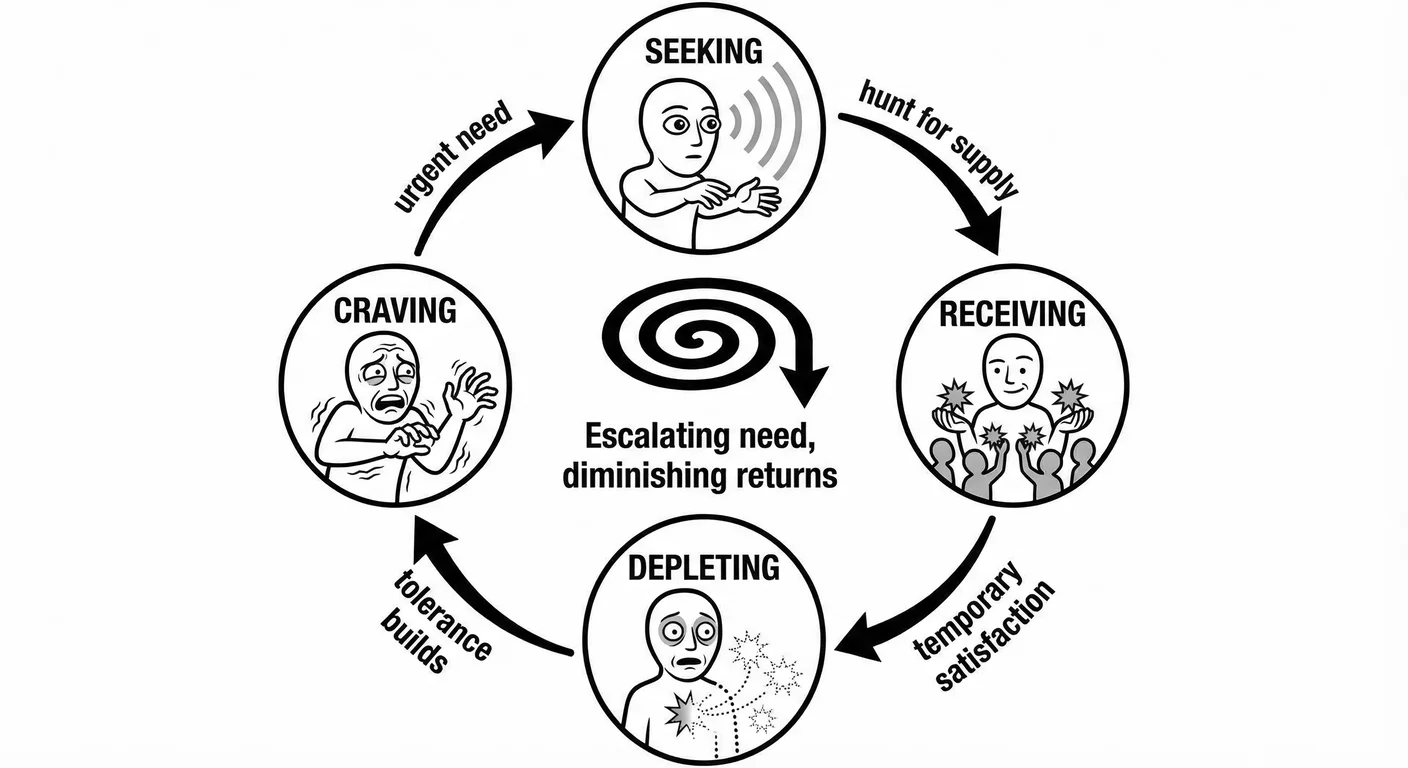

This specialness demands tribute. A healthy person can take or leave compliments. For the narcissist, they are as essential as oxygen. The admiration must be excessive, and increasingly extreme— because like addiction, tolerance develops. What satisfied yesterday feels insulting today. At a party they do not converse but perform. They will constantly scan for reactions and deflate when attention shifts. Partners often describe feeling like forced full-time cheerleaders; any decrease in enthusiasm triggers punishment or rage, often accompanied by sulking withdrawal. Children become mirrors rather than independent people only existing to reflect parental glory.

Beneath the need for admiration lies raw entitlement. A narcissist’s needs take automatic precedence. Denied special treatment, they feel violated. The entitled narcissist does not ask for favours; they assume compliance, often conditioning others to see it as ‘power’ rather than disguised insecurity and entitlement. For this reason, they do not negotiate; they attempt to dictate. Waiters are berated for imperfect service. Children’s needs are perpetually deferred—their time and space subordinate to the narcissist’s. Partners are conditioned until their own needs seem illegitimate, even selfish to voice.

A family therapist in Manchester described a session that crystallised this dynamic. A father had brought his teenage daughter to therapy because she was “difficult”—sullen, withdrawn, failing classes. Twenty minutes in, the therapist gently suggested that perhaps the daughter felt unheard at home. The father’s face shifted. “Unheard? I pay for that house. I pay for her school. I work sixty hours a week so she can have opportunities I never had.” His voice rose. “And you’re telling me she feels unheard?” He stood, gathered his coat. “This is a waste of time. Everyone knows she’s the problem, not me.” At the door, he turned to his daughter: “See what you’ve done? Now I’ve lost an afternoon.” The daughter sat motionless, face blank—then followed him out.

Entitlement enables exploitation. Others exist as functions, not persons. 71 The narcissist assesses what each person can provide—admiration, status, money, cover—and pursues relationships based solely on extraction potential. When depleted or no longer useful, people are discarded without thought. Think of the friend who only calls when they need something, and who disappears without apology during your crises but expects support during theirs. Consider the executive who takes credit for subordinates’ work while blaming them for failures. The romantic partner who isolates you from friends and family until you doubt your own perceptions. Once dependent, partners find savings drained and often their name on debts they never agreed to—while the narcissist moves on unburdened to the next source of supply.

Lacking Empathy Empathy The capacity to understand and share another person's feelings, comprising both cognitive (understanding) and affective (feeling) components—often impaired in narcissism. enables all of it—not simple coldness but genuine inability to recognise others’ feelings as real. 1037 The narcissistic mother, told her child is being bullied, immediately shifts focus to how this reflects on her as a parent. The narcissistic boss, informed an employee’s parent is dying, expresses annoyance about work disruption. The cost in time and support interferes with their goals. Partners in crisis instead of receiving support find themselves comforting the narcissist about how their crisis affects them. Children learn over time their feelings are irrelevant, often invisible, and perhaps even dangerous to express.

The narcissist lives in constant comparison. They envy others’ success while believing everyone envies them. A child’s independent achievement triggers resentment, not pride—the parent feels outshone. A partner’s promotion becomes evidence of their disloyalty. Colleagues’ successes are often met with sabotage disguised as concern.

All of this manifests outwardly as arrogance: an air of condescension, dismissiveness, and even contempt for “ordinary” or “lazy” people. They are often called “sheep” or “unenlightened.” Subordinates and anyone perceived as lower status are treated with barely concealed disdain. Children absorb the message that some people simply matter less, and so grow to fear becoming one of them. Partners watch their friends and family humiliated, and learn that silence is safer than objection.

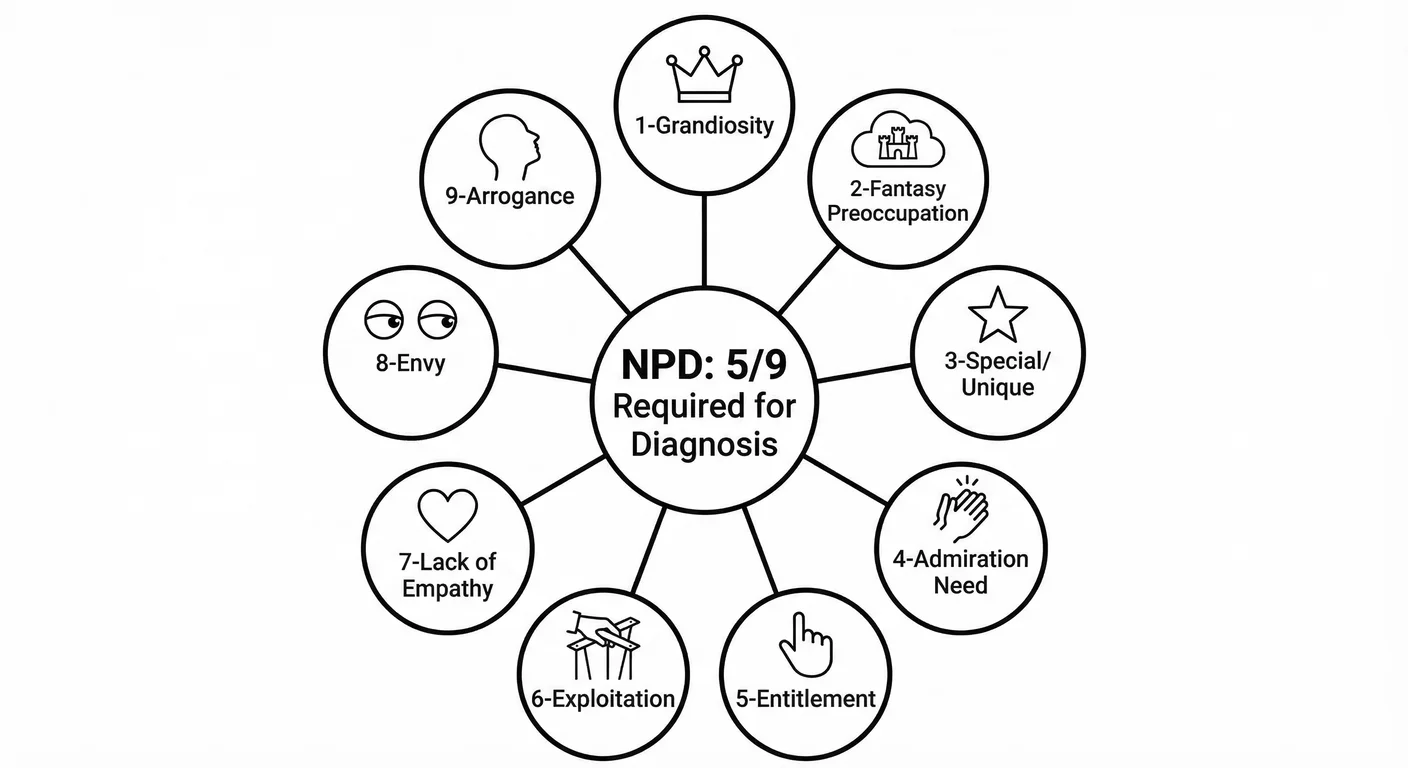

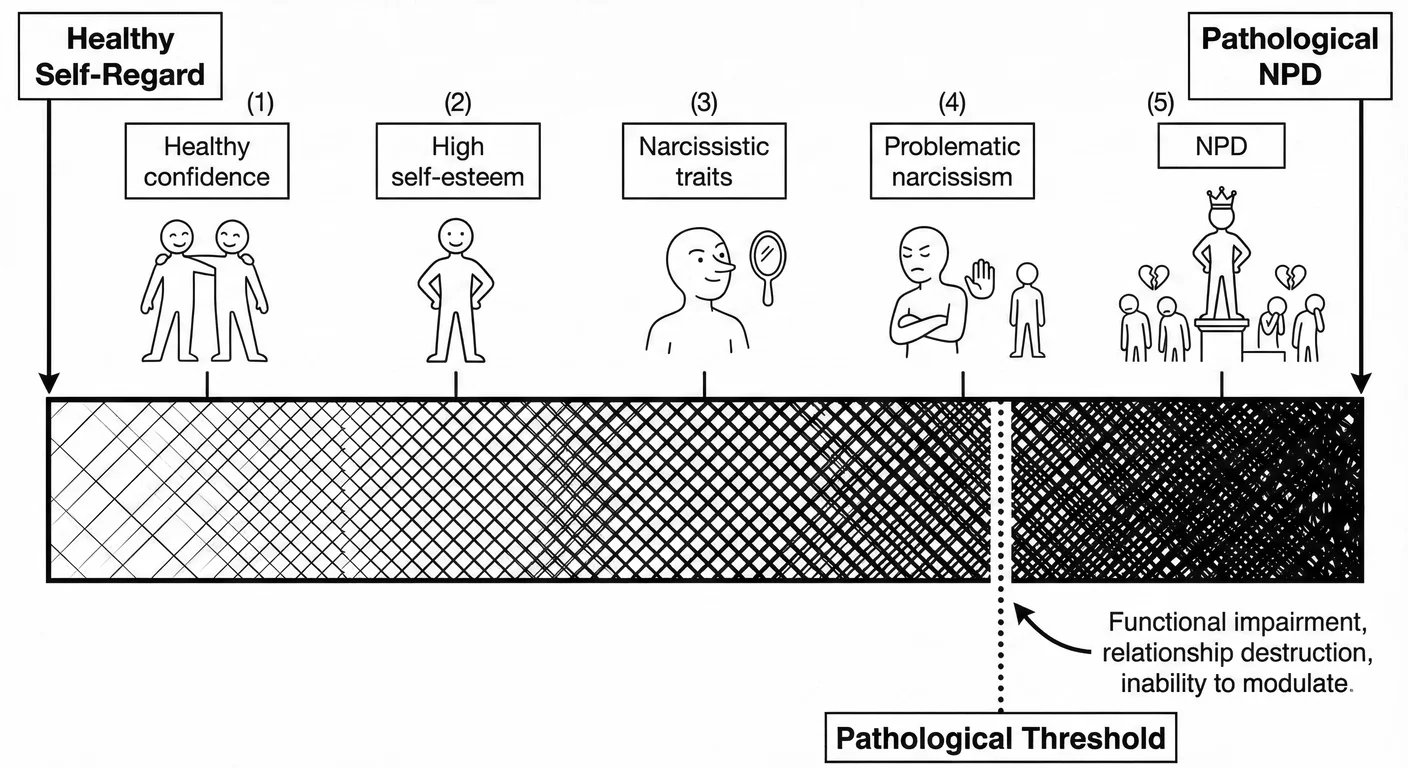

We all have some of these traits, maybe even two or three which surface due to situation or conditioning. However, healthy people try to notice them and correct them because they see the hurt they cause. We feel genuine guilt, remorse, and so do what we can to make amends and seek the balance and reciprocity necessary to bring happiness to those around us. The difference is that narcissists express several of these traits persistently despite the damage they cause. The DSM sets the threshold at 5 of these 9 traits for an individual to be diagnosed with clinical Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

Where Confidence Ends

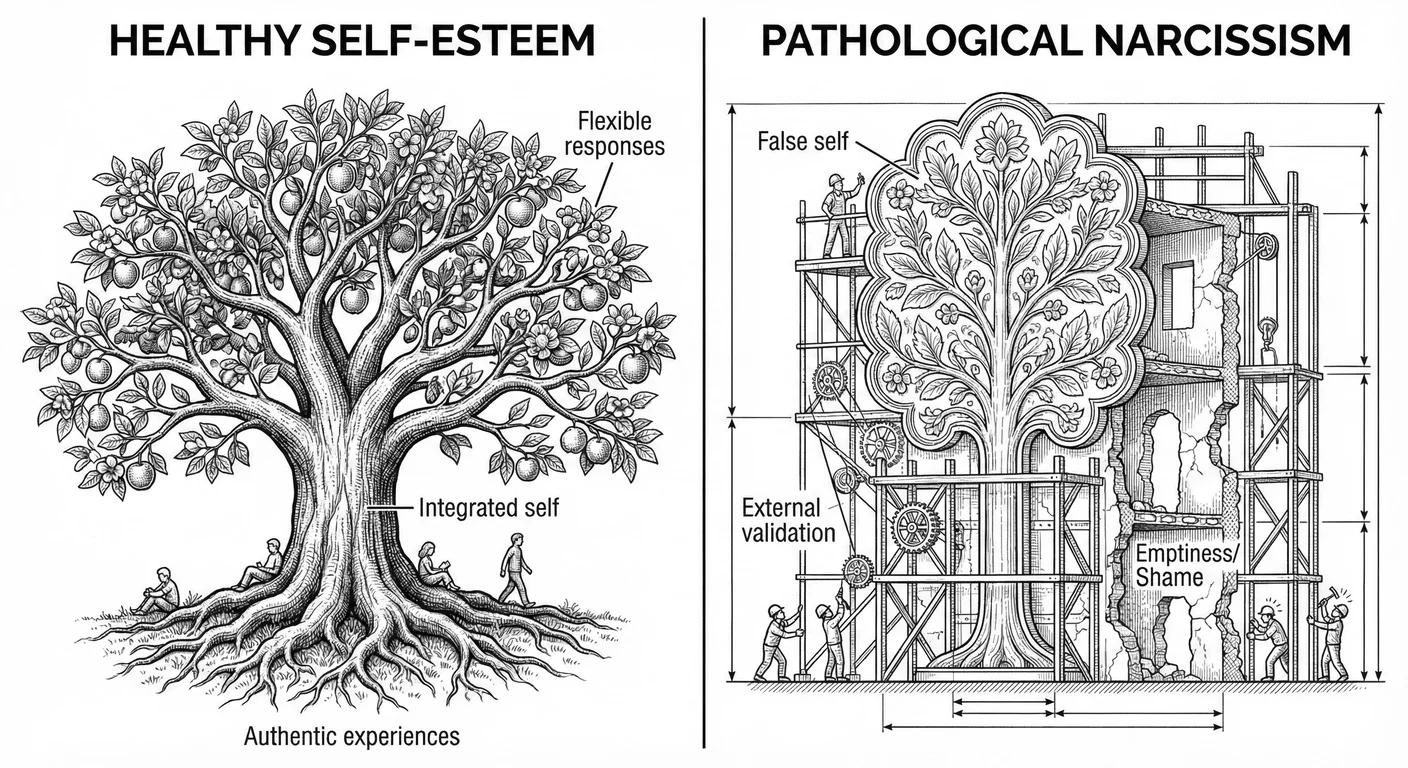

Self-regard is not always pathological, and the difference is vital in understanding ourselves and others. Healthy self-esteem requires realistic self-appraisal: acknowledging our achievements without grandiosity, and taking pride without requiring others’ diminution. 265 The healthy person enjoys admiration but does not need it to survive. It is nice to be acknowledged. By the same token criticism stings to someone with healthy self-esteem but remains tolerable, even becomes useful in repair, adaptation, and improvement. Failure for the healthy is information and not some kind of existential threat. The healthy person can lose a competition, a romantic prospect, even status in the eyes of their community and still feel whole. The narcissist cannot.

All of us fall somewhere on the spectrum, being capable of both healthy self-regard and occasional self-absorption. 1252 The question is where precisely the line falls, and what happens when we cross it. The difference goes beyond degree and into fundamental self-structure, akin to crystallization. In the territory of pathological narcissism there is no self-love and there is not enough coherent self present to experience genuine self-regard. What appears as self-love becomes a desperate attempt to simulate coherence by borrowing from one’s surroundings.

Clinicians call it “contingent self-esteem.” 649 Healthy self-esteem provides stable sustained self-worth. Pathological narcissism creates transient esteem tokens—entirely dependent on external validation or comparison. These tokens lose meaning as the moment passes, draining away and leaving a further void to be filled. This changes the stakes; admiration suddenly becomes more than pleasure; it marks psychological survival. Without Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. comes psychological annihilation.

Functional impairment delivers the clearest diagnostic threshold. When a person’s self-focus begins destroying relationships or causing significant distress, we have crossed into pathology. The successful CEO who drives away talent through tyrannical behaviour, the charismatic partner who leaves a trail of emotionally destroyed relationships—these patterns indicate disorder regardless of achievement levels. Those with pathological traits do not just prioritise themselves; they systematically damage others through exploitation and emotional abuse creating “narcissistic abuse syndrome”: a constellation of visible symptoms including Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) A trauma disorder resulting from prolonged, repeated trauma, characterised by PTSD symptoms plus difficulties with emotional regulation, self-perception, and relationships. and erosion of identity. 42 The pathological threshold is crossed when one’s self-regard suddenly requires others’ diminution.

The Paradox of Fragility

Behind the grandiose exterior lies glass. This is narcissism’s central paradox: apparent grandiosity coexists with extreme psychological fragility. The same person who presents as supremely confident, will, despite claiming to be superior, even invulnerable, react uncontrollably to minor slights with rage or collapse.

The False Self

We know from the research that something went wrong in a narcissist’s childhood. The anchoring relationships that should have said this is who you are—that should have reflected the child’s authentic self back to them—were missing or distorted, and perhaps conditional on performance. Rather than expressing authentic needs and risking rejection, the child then constructed a survival false self designed to secure needed attention and care. 1332

In pathological narcissism this false self becomes elaborately developed and fossilised—rigid. 649 It is a complete personality organisation: a series of social reactions pasted over each other to keep attention and praise coming. These reactions grow to overwhelm the entire natural psyche, spreading until they occupy the space where Authentic Self Authentic Self Your genuine identity—your true feelings, values, and needs—as opposed to the adaptive persona developed to survive narcissistic environments. -experience should reside. Many assume that under the false self lies another authentic self waiting to emerge. It does not. The grandiose false self both shields the organism against shame and attracts the admiration and attention needed for psychological survival.

This hardened false self explains many narcissistic paradoxes. The narcissist seems supremely confident yet constantly seeks validation. This is because the false self, being constructed, is both reactionary and shallow, rather than authentic; it requires that continuous external reinforcement through stimulation to maintain its existence. It cannot self-sustain because of its reactionary nature. The false self must be constantly projected to seem real. The true self, by contrast, develops when a child’s spontaneous gestures are met with affirmation—when someone says I see you, I know you. That foundation makes the self secure and self-sustaining, so no projection is required, and genuine relatedness possible.

False and true selves mutually exclude. Another person’s true self—with its needs, its vulnerabilities—threatens the false self by demanding reciprocal engagement. The narcissist’s terror of authenticity follows from this dynamic. Genuine emotional experience, particularly of need or vulnerability, triggers such anxiety that it must be immediately defended against through grandiosity or rage.

The false self’s content also varies based on what caregivers rewarded in childhood. If they valued achievement, the false self emphasises success. If suffering brought attention, it manifests as perpetual victimhood. Regardless of content, the structure remains the same: a rigid performance that must never falter.

Children with exceptional abilities often become narcissistic supplies for their parents, being valued for their achievements rather than their authentic selves. 864 These children learn to identify with their performance, developing elaborate false selves around their gifts while losing connection to genuine feelings and needs. The resulting adult seems successful but feels profoundly empty, achieving everything while experiencing nothing.

Finally, the false self requires constant maintenance through what clinicians call “narcissistic defences”—idealisation, devaluation, Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. —which usually operate automatically: outside conscious awareness.

This false self—created to ensure survival and acceptance—actually prevents genuine connection. Others relate to the performance. The narcissist, identified with the false self, cannot receive love for their Authentic Self Authentic Self Your genuine identity—your true feelings, values, and needs—as opposed to the adaptive persona developed to survive narcissistic environments. because that self remains out of reach. Like the image in the pool. They love an impossible image of perfection and never who they actually are. They are surrounded by admiration while never receiving any genuine recognition.

The Supply Economy

Validation functions like a psychological nutrient narcissists cannot generate internally. 676 Without regular infusions of admiration, they face a kind of psychological starvation leading to a collapse of the false self threatening psychic annihilation.

Attention comes in many forms, not all obviously flattering. Positive supply includes praise and association with high-status others. But negative forms—fear and hostility—can also feed the false self. In common parlance this can be termed trolling. What matters is impact by being the forced centre of attention and so creating strong reactions in others. Such individuals court controversy or create chaos because negative attention is better than none at all.

They become expert at extracting validation by developing supply acquisition strategies no matter how manipulative. Love Bombing Love Bombing An overwhelming display of attention, affection, and adoration early in a relationship designed to create rapid emotional dependency and attachment. creates grateful, attached suppliers through overwhelming attention and premature intimacy. 1195 Triangulation Triangulation A manipulation tactic where a third party is introduced into a relationship dynamic to create jealousy, competition, or to validate the narcissist's position. —pitting people against each other while remaining at the centre—generates competition to provide supply. 144 Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. creates dependent, compromised suppliers who rely on the narcissist for truth. 1184

A woman described the pattern in her first months of dating: “He texted constantly. Called me his soulmate after two weeks. Flew me to Paris for our one-month anniversary. I thought I’d won the lottery.” Six months later: “He’d mention his ex casually—how much she still wanted him, that sort of thing, how she understood him in ways I couldn’t. Suddenly I found myself competing with a ghost.” A year in: “When I remembered things differently from how he described them, he’d look at me with such concern. ‘You’re stressed, babe. You’re not remembering clearly.’ I started keeping a journal just to prove to myself I wasn’t losing my mind.” These strategies may start as conscious manipulation, or be absorbed from environments where they were modelled; over time though, they become automatic.

The economy of attention operates on principles of inflation and devaluation. Like drugs of addiction, the same amount provides diminishing returns over time. The promotion that would have sustained them for months now barely registers. The partner’s daily admiration becomes invisible, taken for granted. This drives them to seek ever-greater conquests and ever-newer sources.

Supply sources accumulate and eventually form a hierarchy. Primary sources (romantic partners, family, close associates) provide constant admiration; secondary sources like colleagues, acquaintances, and strangers offer occasional validation. Those with NPD maintain networks of attention-providers, cultivating multiple sources to ensure continuous availability. When one depletes, others are ready.

Devaluation and discard follow predictably. 338 A new source initially gratifies through novelty and conquest. The narcissist idealises them, showers them with attention ( Love Bombing Love Bombing An overwhelming display of attention, affection, and adoration early in a relationship designed to create rapid emotional dependency and attachment. ). But novelty fades and the source no longer delivers the intense hit of early days. Devaluation then begins. The once-perfect source becomes flawed and disappointing: inadequate. They are then discarded for fresh targets.

Victims gain crucial insight from understanding this economy: the problem is not them. No one can provide enough validation long-term. Devaluation reflects tolerance development, and never the victim’s actual worth. This realisation liberates those trapped trying to regain approval. They are trapped not by the person but by the disorder itself. Narcissists succeed by preventing this very realisation.

Shortages of attention trigger Narcissistic Rage Narcissistic Rage An explosive or cold, calculated anger response triggered when a narcissist experiences injury to their self-image, far exceeding what the situation warrants. or Narcissistic Collapse Narcissistic Collapse A severe breakdown of the narcissist's false self defences, exposing the shame and emptiness beneath, often triggered by major life failures or loss of supply. . 674 Rage (explosive anger disproportionate to the triggering event) punishes inadequate providers and extracts emergency validation through fear and attention. Collapse manifests as withdrawal, depression, even suicidal ideation when admiration completely depletes, causing the false self to temporarily fragment. Both responses are desperate attempts to restore the false self.

Modern technology has revolutionised the process of exploiting others and finding supply sources. Social media provides quantified, immediate validation through likes and shares. 1248 Narcissists can and do grow vast networks without ever needing to invest in genuine reciprocal relationships. Yet the emptiness persists. Social media validation is often unsatisfying—being too shallow, and all too transient—thus creating an ever-increasing need for more. This partly explains rising levels in social media-saturated cultures. 1255

A Note on Compassion

How do we understand destructive behaviour without excusing it—and maintain compassion without enabling harm?

The narcissist started, fundamentally, as a wounded person. 676 The grandiosity and cruelty that characterise narcissistic personality disorder are there to disguise intolerable shame and emptiness. Understanding this does not excuse the behaviour but can allow enough compassion to engage constructively rather than merely condemn. The abused child who transforms into an abusive parent deserves both understanding and accountability. They remain, like we do, responsible for life choices.

Compassion for narcissists must nevertheless be balanced with protection for their victims. Those harmed by narcissistic behaviour—partners and children especially—deserve priority consideration. Empathy for the narcissist’s wounds cannot override recognition of the wounds they inflict. The therapeutic notion that understanding leads to healing has limits when dealing with individuals who weaponise others’ compassion.

“Vulnerable narcissists” particularly challenge our compassion. 1050 These individuals present as victims, eliciting sympathy and care, but their victimhood is there to feed off others’ empathy—turning it into a form of validation and manipulation. They drain helpers through endless need while punishing attempts at boundary setting, and position themselves as too fragile for accountability. Compassion without boundaries becomes enabling and complicit.

For those in relationships with narcissists, compassion must become enlightened and healthy rather than reflexive. Understanding the narcissist’s psychological structure helps predict behaviour and protect oneself, but extending unlimited empathy will lead to exploitation. All interactions are essentially about supply. Compassion alone cannot heal narcissism, and in fact cannot reach the wound it would need to touch.

Mental health professionals face particular challenges in maintaining therapeutic compassion for narcissistic patients. 1050 These patients actively devalue therapists and terminate treatment when challenged. Yet some narcissists, particularly those facing Narcissistic Collapse Narcissistic Collapse A severe breakdown of the narcissist's false self defences, exposing the shame and emptiness beneath, often triggered by major life failures or loss of supply. , can engage in meaningful therapy. The key in those exceptional cases is maintaining professional boundaries while offering genuine understanding of their suffering.

Those recognising narcissistic traits in themselves face a particular challenge: honest self-examination without either grandiose self-attack or defensive dismissal. The patterns described in this book are not the self—they obscure it. Everyone has narcissistic moments; the question is whether these moments come to dominate one’s relational life. Crucially, the capacity for genuine self-reflection and concern about one’s impact on others already distinguishes the reader who worries they might be narcissistic from those with pathological narcissism. The very anxiety suggests something the true narcissist lacks: a conscience that can be troubled.

The myth tells us Narcissus died staring at his reflection, unable to look away even as he wasted to nothing. But Echo, though diminished, survived. She found caves, lonely places, other voices to carry. The pool held no power over her. She could still hear the world.