Introduction: The Paradox of Healing in a Narcissistic Culture

In a small apartment somewhere in America, Katie sits at her kitchen table at 2 AM, laptop open, searching variations of the same desperate query: “How to know if you are being gaslit.” “Signs of emotional abuse.” “Why do I feel off around him.” “Narcissistic personality disorder relationships.” Each search brings a mixture of recognition and despair—she sees her experience has a name, that others have lived this nightmare; terror at what accepting it will mean for her life, her children, her future. She is exhausted, her nerves frayed. She knows she is bad at expressing herself, indecisive, anxious, seen as ‘stupid’ by the world, and for as long as she can remember no one has really ever listened to her. It will not work. Nothing will work. She has $247 in her checking account, two children sleeping in the next room, and a partner who has systematically burned out every relationship and resource that might help her leave. She feels so alone. One of millions trapped in the living slavery of our time: seeking healing from narcissistic abuse while speared through by systems that not only enable such abuse but actively profit from it. Her life—seen truly—is worse than any Greek tragedy.

Here we take all that prior work and put it to good use. No platitudes about “just leaving” or “moving on.” No pretending that individual healing can occur in a vacuum, unhooked from the causal web of relations that is our world. Our aim is nothing less than overcoming the systems—economic, legal, and cultural—that trap victims with their abusers. This chapter charts a path out: the researched approach developed through decades of clinical work and survivor testimony. The journey from recognition to recovery—from victim to survivor—is one of increasing clarity and restored autonomy. We must also acknowledge a hard truth: some people face greater obstacles to healing because the systems supposedly designed to help them have been captured by the very pathology they seek to escape.

The Double Bind of Recovery

Recovering from narcissistic abuse today presents what Gregory Bateson would call a double bind—a situation where contradictory demands make any response inadequate. Victims are told they must leave abusive relationships for their safety and sanity. People who should be actively helping them lecture them via social media and share resources. On the other hand, the systems supposedly designed to help them—family courts, social services, law enforcement, healthcare—often operate from frameworks that actively enable further abuse. Racist cops dismiss their complaints. Misogynistic bosses punish them for taking time off. Psychiatrists and doctors who do not want the messy long-term work of helping them be free unless the system or insurance covers it properly. Most victims will not have that in place. Through this, they must co-parent cooperatively with someone who uses every interaction as an opportunity for control and punishment. You must be financially independent when your abuser has destroyed your credit, sabotaged your employment, and hidden assets. You must “prove” abuse that leaves no physical marks in courts that barely recognise psychological torture. Especially if you are isolated, perhaps a different colour, or have a disability, or not a native speaker, or they have hurt your ability to speak for yourself freely.

Katie’s 2 AM search for answers represents more than one woman’s crisis; her story illuminates patterns affecting millions. Her situation feels impossible because it is, trapped between statistical realities that chain survivors and cultural contexts that normalise their suffering. The numbers tell us what is happening; the cultural analysis explains why it continues; and the individual stories like Katie’s remind us that behind every statistic is a human being deserving of dignity and support.

The statistics paint a stark picture. Research by the National Network to End Domestic Violence reveals that financial abuse occurs in 99% of domestic violence cases 918 . This is strategic, since abusers understand that economic crippling is the most effective chain. The average victim suffers an income loss of 37% after leaving an abusive relationship, with many facing devastating poverty that can last decades 8 . When we tell victims to “just leave,” we expose the sadism they are trying to escape—as ‘leaving’ often means choosing between abuse and destitution, between violence and homelessness, between psychological torture and losing their children. Do not force someone in pain to choose. That includes yourself by the way.

This economic entrapment intersects with what Christopher Lasch identified as “The Culture of Narcissism”—a society that rewards narcissistic traits while punishing their victims 712 . This is a euphemistic way of saying that the whole culture is infected with narcissistic traits and systems that prevent a level playing field, minimising the fighting chance of victims. The same corporate culture that elevates narcissistic leaders creates workplace environments hostile to abuse survivors. Ask any woman in the workplace in the past 30 years in London or New York. The survivor who needs time off for court dates, who has PTSD symptoms triggered by workplace dynamics, who struggles with the executive dysfunction that follows complex trauma, finds themselves labelled as “problematic” employees. Their career and prospects are stigmatised and sidelined. The narcissist, meanwhile, with their charm and ruthless self-promotion, climbs the corporate ladder, accumulating the resources that make leaving even more difficult. Yet money is not destiny.

Why Traditional Therapy Often Fails

Perhaps nowhere is this kafkaesque double bind more evident than in the therapeutic landscape itself. Survivors seeking help for narcissistic abuse often encounter therapists who, despite good intentions, operate from frameworks that inadvertently enable further harm. The reasons for this failure are systemic, not individual. Most therapeutic training programs provide minimal education about personality disorders and even less about narcissistic abuse dynamics. They may know some keywords, but have no real field or deep experience in the mechanics of abuse or how the dynamics manifest in real modern situations. A therapist trained in general couples counselling, armed with techniques designed for relationship enhancement between genuinely caring partners, becomes an unwitting accomplice to abuse when applying these exact techniques to narcissistic relationships. Narcissists know this and often use those same systems as shortcuts or traps, or punishment, or false hope followed by confirmation of their partner’s worthlessness.

The “neutral stance” that therapists are trained to maintain—the refusal to “take sides,” the assumption that “both parties contribute to relationship problems”—becomes actively harmful when one party is a manipulative abuser. This is particularly absurd in a situation where one party is a malignant narcissist, projecting an aura of victimhood and being misunderstood because of their undiagnosed ‘bipolar’ condition or more recently their subtle Asperger’s. In couples therapy, the narcissist performs vulnerability, takes “accountability” that lasts exactly as long as the session, and learns new psychological vocabulary to weaponise against their victim. They discover their partner’s deepest wounds and fears, revealed in the supposed safety of therapy, and use this for more targeted, even more sadistic attacks. Meanwhile, the victim, speaking their truth in front of their abuser, faces punishment at home away from protection and accountability for every revelation, every boundary attempted, every moment of clarity achieved. Often narcissists will soften them up by pretending to accept, understand, and try to change before switching back as soon as they can see the hope return, as that will gain them the maximal pleasure from their partner’s suffering.

Research by Stith and colleagues found that couples therapy not only fails in abusive relationships but actively increases danger for victims in the majority of cases 1188 . Yet many therapists, lacking training in power dynamics and coercive control, continue to recommend it. They follow protocol. They encourage “communication” with someone who uses every conversation as warfare. They promote “compromise” with someone who views any concession as weakness to exploit. They push “forgiveness” before the victim has even achieved real safety, inadvertently aligning with the abuser’s agenda of minimisation and premature reconciliation. Therapists can and should be accountable for outcomes in these cases.

The healthcare and especially medical insurance landscape compounds these problems. Most plans cover just 8-12 sessions of therapy per year—barely enough to establish trust with a complex trauma survivor, let alone begin meaningful healing. Perversely, the therapists who do specialise in narcissistic abuse recovery often do not accept insurance, knowing exactly how hard and draining being around narcissists can be, making their services inaccessible to those whose abusers have left them financially devastated. So Katie, the survivor, is left cycling through inadequate care, each failed therapeutic encounter reinforcing the narcissist’s narrative that they are “too difficult,” “untreatable,” or “the real problem.” This would be like turning up to the emergency room and having the doctor diagnose a broken leg, and then saying “Walk it off.”

Reframing Recovery: Beyond Individual Pathology

Our path out, for Katie, is different. The medical model’s focus on individual pathology—diagnosing the survivor with depression, anxiety, PTSD, as if these are diseases arising spontaneously within them—misses the reality that these are normal responses to abnormal situations, predictable and documented. Why is this so? The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study revealed that 67% of the population has experienced at least one significant childhood trauma, with serious implications for adult mental and physical health 381 . That is two out of any three people. Abuse forms part of broader patterns of developmental trauma, often intergenerational, never an isolated incident. Our focus shifts from “what is wrong with you?” to “what happened to you?”

This shift, championed by trauma-informed care advocates, recognises that the symptoms we pathologise—the hypervigilance and emotional dysregulation examined in Chapters 3 and 11—are actually adaptations that allowed survival in impossible circumstances. The woman who “cannot trust anyone” learned through brutal experience that trust leads to betrayal. She is not wrong about this, that is what the world showed her, and like any child growing up with that as reality, she believed it. The man who “overreacts” to minor slights developed a hair-trigger alarm system in an environment where missing subtle warning signs meant being hit by a parent until they expressed enough suffering the parent’s sadism was satisfied. The survivor who “cannot let go of the past” is trying to process trauma that was never allowed completion, interrupted by the next crisis, the next attack, the next desperate attempt at survival. He cycles through layers of incomplete pain, forced to go around in circles but with never enough fuel or time to complete even one ‘lap’ of this inner circuit. These are not personality flaws or weaknesses, they are mechanisms. They are our friends. Without them, the crime would leave no trace.

Neuroscience research explored in Chapters 5–7 supports this reconceptualisation. Bessel van der Kolk’s work demonstrates that trauma literally changes brain structure—measurable, observable alterations in neural architecture 1272 . The amygdala becomes hyperactive, scanning constantly for threat. The hippocampus, responsible for organising memories, shrinks under chronic stress, leaving traumatic experiences floating in an eternal present. Forever unable to reliably remember the trauma in an attempt to shield and preserve their mental state, at a huge cost in the rest of their living. The prefrontal cortex, our centre of executive function and emotional regulation, goes offline when triggered, to prevent degradation, with the horrific effect of leaving the survivor at the mercy of primitive fight-flight-freeze responses. Again, these are not character weaknesses or mental illnesses in any traditional sense—they are injuries, as real as broken bones mentioned earlier, requiring actual interventions, and compassionate work for healing.

The political dimensions of personal healing cannot be ignored. As feminist therapists have long argued, “the personal is political”—individual suffering reflects and reinforces broader systems of oppression. The woman trapped with her narcissistic husband is also bound by wage gaps, inadequate childcare, social mandates of caregiving, and family court systems that prioritise fathers’ egos over children’s safety, dominated by mostly male judges and lawyers. The adult child of narcissistic parents attempting to heal confronts not just personal trauma but cultural stereotypes masquerading as archetypes about family, about honouring parents regardless of harm, about blood being thicker than water even when that blood is poison, burning them from the inside out.

Recovery, then, is both personal healing and active political resistance. Freedom is paramount, and free will must be given space to operate. Choices must be real again. Every survivor who breaks free weakens the structures that enable narcissistic abuse. Every story told publicly challenges the silence that protects abusers and echoes in every decent person’s heart. Every boundary maintained despite family pressure, every “no contact” decision upheld despite social condemnation, every refusal to accept blame for abuse received—these are revolutionary acts of courage in a culture that feeds on victims’ suffering for its continuation. Only the brave make it back to themselves.

The Survivor’s Journey: From Recognition to Recovery

The journey from narcissistic abuse to home is not a linear path. It spirals and circles back, stalling in places no guide predicted. Yet patterns always emerge—give yourself time to breathe and you will see them. Stages that most survivors pass through, each with its own challenges and possibilities for growth, are as real as your journey to work. Understanding these stages provides something better than the traditional self-help ‘roadmap’: a powerful framework, a way to locate oneself in the journey and the terrain surrounding your real self, allowing you to anticipate and reliably overcome what may come next.

Stage 1: Recognition and Naming—The Shattering of Denial

It is a good and wonderful fact that recognition rarely arrives as a single moment of clarity but rather as a slow accumulation of evidence that eventually becomes impossible to deny. This is healthy and shows the survivor is turning towards genuine wellbeing. For months or years or even decades, the survivor has explained away each incident, rationalised each cruelty, accepted blame for each explosion. These things have definite causal effects, adding up. They have believed they were too sensitive when told their feelings were wrong, too demanding when basic needs were unmet, too difficult when they asked for respect. The narcissist’s reality-distorting narrative became their own inner voice, a colonisation of consciousness so complete that the survivor genuinely cannot distinguish between their perceptions and the abuser’s projections.

Then something shifts—a miracle happens. Perhaps they stumble across an article about gaslighting and recognise every tactic. Perhaps a friend, witnessing an interaction, names what they see as abuse. Perhaps the narcissist, grown comfortable in their control, escalates beyond what even the survivor’s compromised reality-testing can rationalize. A beautiful crystallisation happens. And yet, recognition, when it comes, brings terror before relief. If this is abuse—if it has always been abuse—then everything the survivor believed about their relationship crumbles simultaneously. It is never like the movies—these moments are mixed, comprising stunning clarity and a wellspring of inner emotion. The knot has loosened, and things are starting to flow again, but it is just the beginning, and it is powerful, and yet so fragile.

The statistics around recognition are sobering. It takes an average of seven attempts before a victim successfully leaves an abusive relationship 907 . The statistic reflects how severely abuse disrupts the very cognitive functions needed to recognise and escape it. Attachment hijacking and the mechanisms discussed earlier literally paralyse certain psychological faculties. Each return is part of a learning process, however much it feels like failure and is judged that way externally. It is gathering evidence, testing whether change is possible, double-checking they are on new solid ground, building resources both material and psychological for the next attempt. It presents hope but at the same time multiple opportunities for narcissistic abuse to worsen.

Melanie Tonia Evans describes her recognition process in her book You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse. 365 After over five years of abuse, she was “at the point of no return”, her health destroyed, her sense of self obliterated. “I thought I was the problem,” she writes. “He was so convincing, so consistent in his narrative that I was crazy, oversensitive, impossible to please. I went to therapy to fix myself, read self-help books, tried every communication technique. Nothing worked because I wasn’t actually the problem.” Recognition, when it came, brought not relief but terror. “At first I didn’t realise that my story was so many other people’s story. Initially I just thought I was trying to survive an isolated cataclysmic event in my life that was beyond the horrors of what I had ever known possible.” That recognition evolved into the foundation for her Narcissistic Abuse Recovery Program, which has now helped over 80,000 survivors worldwide.

Nulling

: Removing Gaslighting and Cognitive Dissonance

Gaslighting (the systematic denial of someone’s reality explored in Chapter 16) generates a very specific type of cognitive damage that makes recognition extraordinarily difficult. While we examined the nulling concept there, here we are going to apply it directly to your journey. The survivor exists in a state of perpetual cognitive dissonance, forced to hold two incompatible truths simultaneously: their lived experience of harm and the narcissist’s denial that harm is occurring. This is only possible due to the attachment hijacking outlined previously—the source of threat and lies convinces them they are the only source of comfort and truth. The psychological suffering of this dissonance is so intense that the mind seeks resolution by any means necessary. Since confronting the narcissist only brings more gaslighting, after all reality cannot be the opposite of itself, so I must be unstable, I must be wrong, I need to depend on the ‘truthgiver’. And so they never bypass the bind, and end up doubting themselves.

Because of this we are going to introduce a new, hopefully more helpful term, and call it nulling. In formal logic, null is an absence of data—a placeholder where meaning should be, but is not. Nulling is the narcissist’s attempt to void the victim’s ability to reason from a solid understanding of reality. By making claims without evidence, denying documented events, and rewriting shared history, the narcissist breaks down the victim’s self-esteem, agency, and reasoning ability. The victim’s grasp on reality becomes unstable—which is precisely the point.

The problem with calling this “gaslighting” is twofold. First, the term is idiomatic—it references a 1944 film most people have not seen, and its meaning has become diluted through overuse. Second, accusing someone of gaslighting triggers narcissistic injury and escalates the confrontation. Nulling is cleaner. It describes what is actually happening: the insertion of void where meaning should exist.

Why normal responses fail. Gaslighting typically occurs where there is vulnerability or a power differential—parent over child, employer over employee, abuser over dependent partner. A normal response to false claims would be to present evidence and expect the other party to accept it. But this requires the narcissist to agree to be reasonable and fair-minded, to accept documented truth when presented. They deliberately will not. The victim who tries to argue, explain, or prove their case (JADE: Justify, Argue, Defend, Explain) provides exactly the emotional engagement—the supply—the narcissist sought.

The Null Protocol. The defence against nulling is the null protocol: recognising that for any statement about reality to be credible, it must be convincing not just to the narcissist but to the world. Their claim is not established, not believable, until they provide evidence that would convince any reasonable observer.

The survivor’s response, therefore, is not to argue but to defer. All supply—through JADE, through emotional reaction, through acceptance of their version—is withheld until the narcissist provides a reasonable, logical, evidence-based argument. If they cannot, their nulling attempt is recognised for what it is: void, null, white noise. If they do provide something, the victim can have it checked independently before accepting it.

This forces the narcissist into an uncomfortable position: either work for their supply by constructing a credible argument (which exposes their claims to scrutiny), or abandon the attempt because it has become boring and unrewarding. The machinery inside them is not built for patient, evidence-based discourse. They are forced to move on.

From Gaslighting to Nulling

The term “gaslighting” implies a contest of realities: I see blue, you say red. The trap is that by arguing for “blue,” you validate “red” as a competing possibility. You treat the narcissist’s delusion as a valid counter-argument that requires rebuttal. It does not.

The narcissist’s contribution is informationally empty—no competing truth at all.

We discussed solid ground earlier, and the most solid ground for testing reality is the Null Hypothesis in science. The “null hypothesis” states definitively there is no effect or relationship until proven otherwise. In contrast narcissists are saying the world is different because I said so. “I’m a great father. I make a lot of money.” “I’m the best mother in the city—my kids never call me because they are so independent.” “The economy is great! Prices are DOWN” These increasingly desperate claims fizzle when unfed—when met with the null protocol rather than emotional engagement—and they then become embarrassing evidence of the narcissist’s arrested development and immaturity. They become part of the survivor’s arsenal of evidence that the narcissist cannot face reality.

Most narcissistic communication consists, therefore, in pure assertion without supporting valid arguments, reasoning, or any convincing evidence:

“You are crazy.” (Assertion)

“Everyone hates you.” (Assertion)

“I never said that.” (Assertion)

An assertion without evidence is simply noise. It carries no semantic weight. It contributes nothing to the human understanding of reality. It is null. To break free, one must not react against null statements. Instead, you respond peacefully as a gentle auditor of reality. You ask a single, boring question:

“What is the evidence for that?” or “How do you know that?”

better still: “How can you know that?” “How can one know that?”

The Narcissist: “You are always so selfish.”

The Null Check: “That would be easier to accept if you provide something convincing. Tell me the dates and actions you have noticed and why they’d be provably selfish to everyone. Of course I want to believe you, but without that, no one can.”

The narcissist cannot provide evidence because they operate through feeling, not fact. They also want you to do the work of hurting yourself. When forced to think and actively show they have been tracking and cataloguing your deeds and words to use against you, it reveals the disgusting truth about their contempt for you. That threatens them directly. When they fail to present or scramble to reframe, their statement remains null.

Unlike with gaslighting, you do not need to be “strong” to ignore a nulling event—you just need to relax and be logical. A whole arsenal of reasoning exists, and every thinking person in the world is on your side, so you can relax. It may take a few times, but they will quickly realise it is a waste of their time, leads to work, and is boring. The machinery inside them is not built for it, so they are forced, sometimes over such dead ends, to learn to move on.

When one views their speech as nulling—an attempt to insert meaninglessness into your reality—you stop feeling “crazy.” You feel bored. You realise you are arguing with a glitch. And you can simply step over it.

Gaslighting leaves the victim thinking: “Is my memory wrong?” (Uncertainty).

Nulling makes the victim think: “Where is the grounding in truth?” (Certainty).

For those caught in the uncertainty of the gaslighting cycle, this self-doubt becomes so reflexive that survivors often continue gaslighting themselves long after leaving the relationship. They minimise their experiences (“It was not that bad”), question their memories (“Maybe I’m remembering it wrong”), and accept blame (“If I had just been different…”). Breaking through requires external validation—someone outside the narcissist’s reality distortion field who can confirm that yes, this is abuse; no, you are not crazy; yes, this is as bad as you think it is. The nulling they do is designed to rob the victim of meaning, of the power to engage their authentic self with the world that is theirs. Because their reality is denied, they are fed increasingly meaningless substitutions for fact.

Psychoeducation is often the first step towards recognition. Learning that narcissistic abuse is a recognised pattern, that thousands of others have experienced identical tactics, that there is vocabulary for what happened to them—love bombing, devaluation, discard, hoovering—offers a framework that makes recognition possible. The YouTube channels of psychologists like Dr. Ramani Durvasula, with millions of views on narcissistic abuse topics, have become lifelines for survivors worldwide. The comment sections become impromptu support groups where survivors share stories and validate each other’s experiences in ways that formal therapy often fails to provide. These platforms offer accessible psychoeducation and community support to those who cannot afford traditional psychiatric care.

While the Nulling protocol offers a practical tool for managing the narcissist’s reality distortions, survivors often find themselves struggling with a more insidious barrier to recognition: the powerful emotional and neurochemical bonds that keep them connected to their abuser. Even when the mind clearly sees the abuse, the body may crave the relationship with an intensity that defies logic. Understanding trauma bonding—its neurobiological basis and addictive properties—helps survivors recognise that their difficulty leaving reflects powerful biological mechanisms that must be addressed with the same seriousness we would apply to breaking any addiction.

Understanding Trauma Bonding

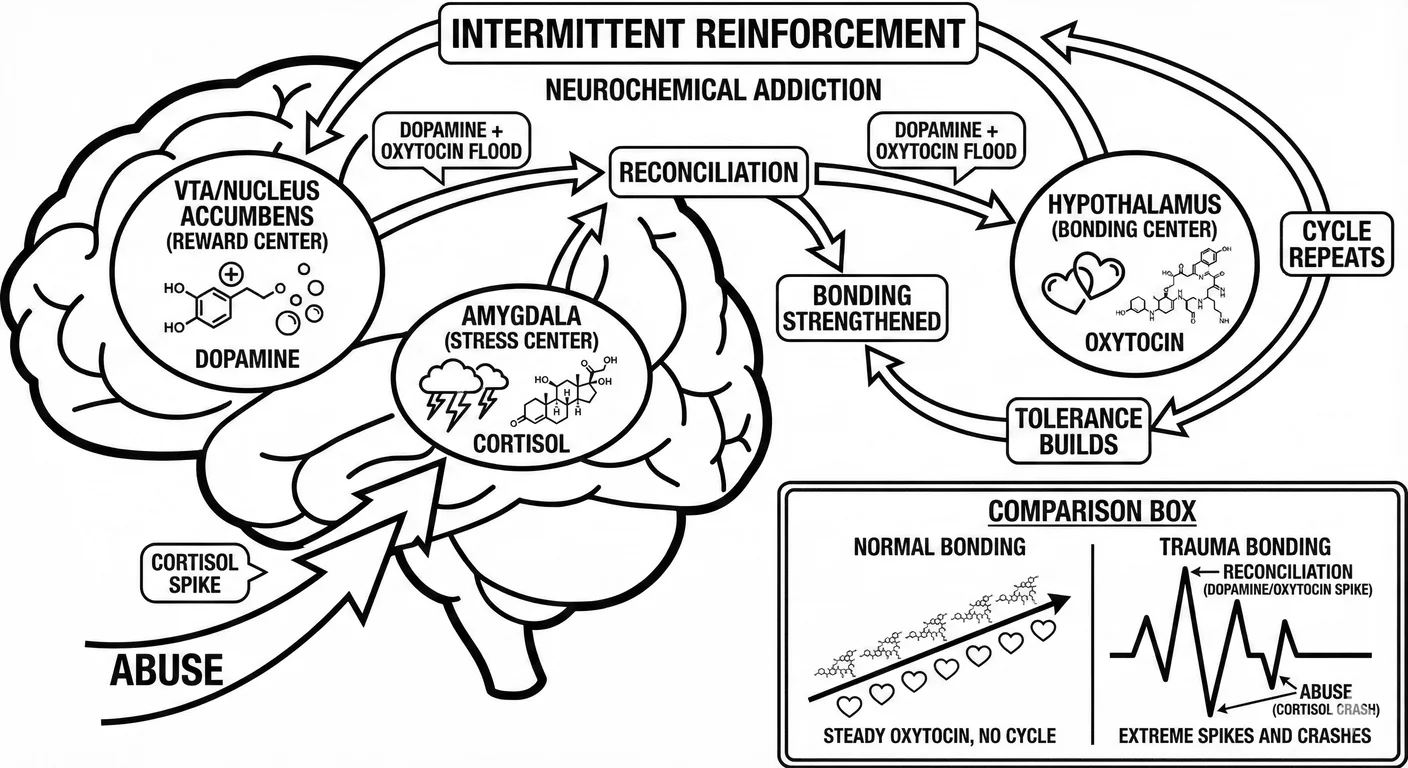

Recognition is complicated by trauma bonding, the psychological attachment explored in Chapter 3 that develops through cycles of abuse and intermittent reinforcement. This attachment is extremely difficult to break. B.F. Skinner’s research on operant conditioning demonstrated that intermittent reinforcement forges the strongest behavioural patterns, more powerful than consistent reward or consistent punishment 1145 . The narcissist, with a reduced pre-frontal cortex, and intermittently malfunctioning amygdala produces this pattern naturally. Their nature, whether consciously or instinctively, exploits this psychological principle. Periods of cruelty alternate with moments of kindness, rejection with love-bombing, devaluation with idealisation. The survivor’s neurochemistry becomes addicted to the cycle—the relief and euphoria when abuse temporarily stops, the dopamine hit when the narcissist briefly returns to their charming false self.

This is literal neurochemical dependence. The same brain regions activated in substance addiction light up in brain scans of people describing their attachments to abusive partners. Oxytocin, the bonding hormone, floods the system during reconciliation, creating powerful attachment even to someone causing harm. Cortisol from chronic stress paradoxically strengthens traumatic memories, making the abuser feel more significant and more central to existence than healthy relationships ever could 213 .

Breaking trauma bonds requires understanding them as a neurobiological phenomenon, not a character flaw. A set of mechanisms overriding free will. The survivor who returns repeatedly to their abuser is experiencing withdrawal as real as any heroin user’s. Research suggests it takes an average of 18-24 months of no contact for trauma bonds to significantly weaken, though some survivors report intrusive thoughts and trauma responses years after leaving 205 . This timeline often shocks survivors who expected to “just move on” after leaving, not understanding that their entire nervous system needs rewiring. The damage narcissism inflicts is real, and long lasting. They literally rob you of your real self, to sustain their false self.

The Seven-Attempt Reality

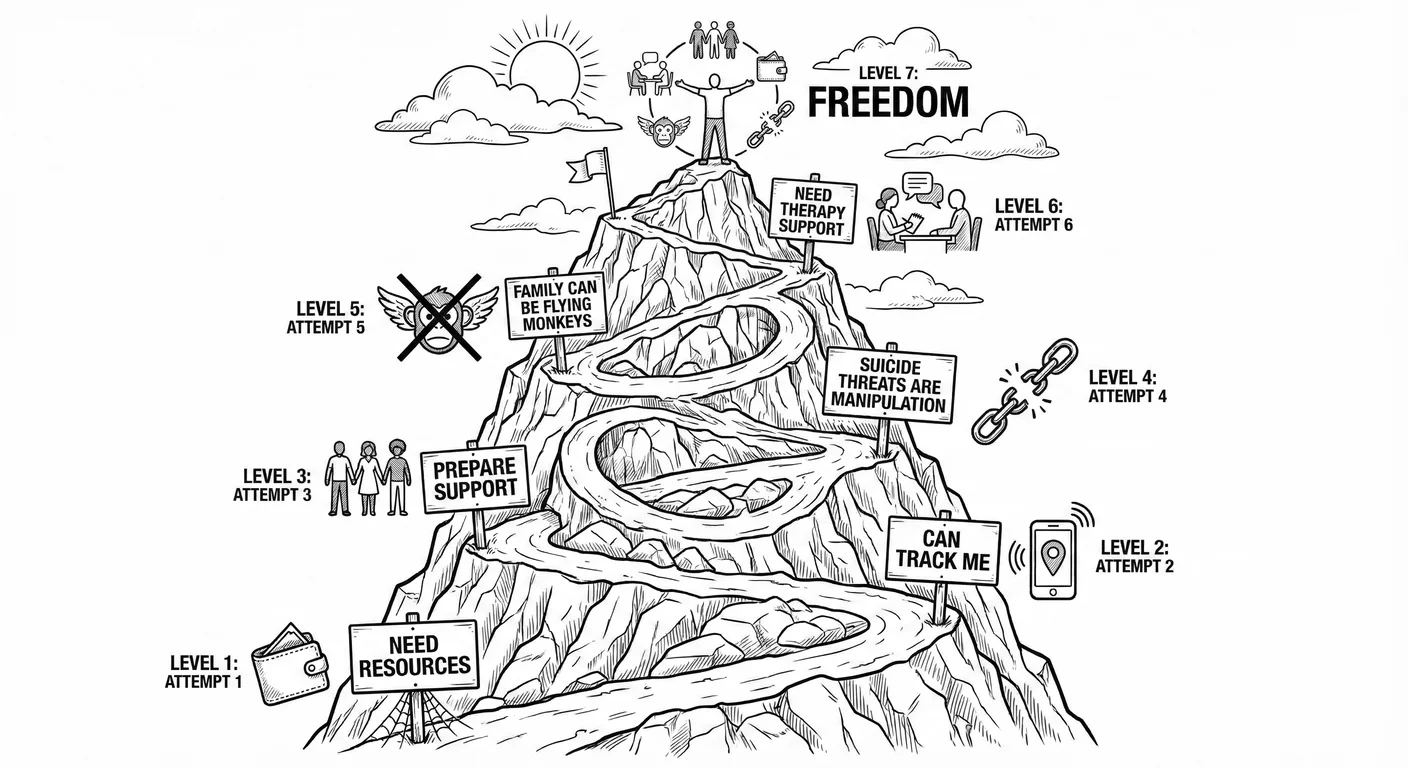

The statistic that victims attempt to leave an average of seven times before succeeding deserves deeper examination. Each attempt is an important information-gathering mission. Lisa, a survivor of a ten-year marriage to a narcissist, maps her seven attempts:

“Attempt one: I left after he screamed at me for three hours about loading the dishwasher wrong. I came back after two days because I had nowhere to go and no money. Lesson learned: I needed resources.

Attempt two: I saved $500 in secret and left again. He found me through my phone location, convinced me he’d changed, would go to therapy. I believed him. Lesson learned: He could track me, and promises meant nothing.

Attempt three: I turned off location services and left. He called my employer, my mother, my sister, telling them I was having a mental breakdown. The pressure was unbearable. I went back. Lesson learned: I needed to prepare my support system.

Attempt four: I told select people the truth before leaving. He threatened suicide, sent me photos of pill bottles, called from the hospital. I could not live with his death on my conscience. Lesson learned: Suicide threats were manipulation.

Attempt five: I did not respond to the suicide threats. He got my mother to call, sobbing, begging me to ‘just talk to him.’ He’d convinced her I was being cruel. I caved to family pressure. Lesson learned: Family could become flying monkeys.

Attempt six: I left and went completely no contact with him and anyone who might pressure me. But I was alone, terrified, having panic attacks. The isolation felt worse than the abuse. I went back. Lesson learned: I needed therapeutic support.

Attempt seven: I had a therapist, a lawyer, a safety plan, a separate bank account, a new phone he could not track, friends who understood, and a journal documenting years of abuse. This time, I did not go back.”

Each return provided important information about what would be needed for successful escape. The journey from attempt one to attempt seven took Lisa four years, but each attempt built the foundation for eventual freedom.

Lisa’s seven attempts illustrate an important truth: leaving is a complex process of preparation, encompassing attempting and refining strategy. She is showing heart and determination. She is disentangling herself in stages: loosening the knot one step at a time. Each “failed” attempt brought her closer to success by revealing what resources, knowledge, and support she needed. With this understanding, we can examine Stage 2—Extraction and Safety—not as a single dramatic exit but as the culmination of careful planning informed by everything learned through previous attempts. The logistics of leaving safely require addressing multiple interconnected systems of control that abusers deliberately create to prevent escape.

Stage 2: Extraction and Safety—The Logistics of Leaving

Leaving a narcissistic abuser is a process that often begins months or years before physical departure. The survivor must become a secret agent in their own life, maintaining a facade of compliance while systematically preparing for escape. This doubleness—performing submission while planning rebellion—requires enormous psychological resources at a time when the survivor is already depleted from chronic abuse.

The No Contact Challenge

No contact is often the only way to break trauma bonds and begin healing. But modern implementation presents challenges: digital surveillance (71% of abusers use technology to monitor victims 919 ), legal barriers when children are involved (58% of abusers who seek custody receive it 845 ), and financial entanglement requiring minimal contact.

When complete no contact is impossible, Grey Rock and BIFF methods (detailed in Chapter ) provide survival strategies for necessary interactions. Grey rock is not a long-term solution—it is a survival strategy while planning extraction or managing unavoidable contact.

While grey rock offers a psychological shield during unavoidable interactions, it represents only one component of a full extraction strategy. The emotional disengagement must be paired with practical preparations that address the multiple ways abusers maintain control. Modern technology has transformed the process of leaving, creating new vulnerabilities that require careful handling. A survivor’s safety plan must therefore span multiple dimensions—digital, financial, legal, and physical—each requiring specific actions taken in careful sequence to avoid triggering the abuser’s suspicion or retaliation.

Safety Planning in the Digital Age

Creating safety in the context of leaving a narcissist requires both digital and physical security measures that many survivors do not know they need until it is too late. A thorough safety plan might include:

Digital Safety:

-

New email account created on a device the abuser has never accessed

-

New phone with a number the abuser does not know

-

Two-factor authentication on all accounts

-

Password manager with complex unique passwords

-

Regular checks for tracking apps and AirTags

-

Social media locked down or deleted entirely

-

Cloud storage reviewed for shared access

-

Smart home devices reset or removed

-

Car GPS systems checked for tracking

-

Children’s devices monitored for surveillance apps

Documentation:

-

Journal of incidents backed up in multiple locations

-

Screenshots of threatening messages saved to cloud

-

Financial records photographed or copied

-

Medical records documenting injuries or stress-related conditions

-

Children’s behavioural changes documented

-

Witness statements collected when possible

-

Police reports filed even when no action taken

-

Therapy records documenting abuse impact

Physical Safety:

-

Safety plan shared with trusted friends

-

Code words established for emergencies

-

Important documents stored outside the home

-

Go-bag packed with essentials

-

Multiple exit strategies planned

-

Safe house identified

-

Legal protections explored (restraining orders, orders of protection)

-

Security systems installed at new residence

-

Work informed of safety concerns

-

Children’s schools notified of custody arrangements

You can find all these resources and more in Chapter .

The financial requirements for leaving safely are substantial—research suggests victims need an average of $5,000-10,000 to successfully leave an abusive relationship, money for housing deposits, legal fees, and the thousand unexpected expenses that arise when rebuilding a life from nothing. For survivors whose abusers have destroyed their credit, hidden assets, or sabotaged their employment, accumulating these resources while maintaining the facade of compliance requires years of secret planning. Each survivor has run a marathon while starving and under attack by their world, and the one person everyone thinks loves them.

Once physical safety is established—when the survivor has successfully extracted themselves and created barriers against further harm—a different kind of work begins. The adrenaline that fueled the escape dissipates, and in its place comes something unexpected: overwhelming grief. This emotional reckoning cannot begin while still in danger; the psyche protects us from feeling the full weight of loss while we need our energy for survival. But in safety, the protective numbness lifts, revealing wounds that demand attention. This grief is complex, encompassing multiple layered losses that must be acknowledged.

Stage 3: Grieving is Good.

“The wound is the place where the Light enters you.” —Rumi

Once physical safety is achieved, the psychological work begins in earnest. The survivor must grieve not just the relationship but the person they thought they loved, the future they thought they were building, the past they must now reinterpret through the lens of recognition. Dr Pauline Boss terms this “ambiguous loss”—mourning someone who is physically alive but psychologically gone, or perhaps was never real to begin with 140 . It is also, significantly, the grief for themselves—all the parts and opportunities, hopes and dreams lost along the way. It is a deep, living grief, without the support of memorials, and it provides what the narcissist never would—closure.

The Person Who Never Existed

The narcissist’s false self—that charming, attentive, loving person who appeared during love-bombing—was never real, but the survivor’s attachment to that illusion was genuine and must be mourned as such. Jennifer, three years out of a relationship with a narcissist, describes this particular agony: “I fell in love with someone who never existed. The man I loved was a character he played to hook me. Once he had me trapped—financially, emotionally, with two kids—the mask came off. But I spent years trying to get that first man back, not understanding he was never real. How do you grieve someone who never existed? How do you mourn a relationship that was a lie from day one?”

This grief is complicated by the gaslighting that makes survivors doubt their own memories. Was it all bad? Were there genuine moments of connection, or was every tender moment calculated manipulation? The narcissist’s occasional kindnesses—which may have been genuine in the moment, as narcissists can experience positive emotions when it serves them—become impossible to interpret. The survivor is left grieving what was lost and the inability to trust their own memories of what was.

The photograph albums tell competing stories. Here is the family vacation where everyone is smiling—but the survivor remembers the rage that preceded it, the silent treatment that followed, the walking on eggshells between snapshots. Here is the wedding day, radiant with hope—but now the survivor sees the red flags they ignored, the warning signs from friends they dismissed, the gut feelings they overrode. Every happy memory is contaminated by the knowledge of what came after, yet those memories still hold emotional charge, creating a grief that feels like a betrayal of both past and present self.

Processing the Theft of Years

Beyond grieving the relationship itself, survivors must process the magnitude of what was stolen from them—years, sometimes decades, that can never be recovered. The woman who spent her twenties and thirties with a narcissistic husband mourns the children she did not have because he sabotaged her pregnancies or refused to commit. The man who spent twenty years building a business with a narcissistic partner mourns not just the financial loss when the individual destroyed it all in revenge but the alternative life he might have built with those two decades.

Diana, now 55, reflects on thirty years with a narcissistic husband: “I do not just grieve the marriage—I grieve the person I could have been. I was accepted to medical school when we met. He convinced me to defer, then to decline, because ‘our love was more important than any career.’ I grieve the doctor I never became, the patients I never helped, the financial independence I never achieved. I grieve the friendships I lost because he isolated me, the relationship with my sister he destroyed with his lies, the confidence I had at 25 that he systematically demolished. How do you calculate that loss? How do you mourn decades of unlived life?”

This grief often includes professional devastation. Research indicates that 64% of domestic abuse survivors report significant career setbacks due to their abuser’s interference 1075 . The narcissist who called repeatedly during work, who created crises before important presentations, who insisted on relocating just as promotions became possible—their sabotage compounds over years into permanent economic disadvantage. The survivor at 50, starting over in entry-level positions, grieves not just income but professional identity, retirement security, the compound interest of a career never allowed to flourish.

Rage as a Necessary Stage

At some point in grieving, the fog of confusion and self-blame lifts, and rage arrives—pure, clean, clarifying rage at what was done to them. This rage is often terrifying to survivors who have been conditioned to suppress anger, who have been told their anger is “crazy,” “abusive,” “unfeminine,” or “unchristian.” But anger is a messenger, carrying vital information about boundaries violated, harm endured, injustice perpetrated. Women’s anger in particular is pathologized in a culture that depends on female compliance. 235

The rage, when it comes, may feel volcanic—overwhelming, uncontainable, threatening to consume everything in its path. Survivors report fantasies of revenge, of exposure, of the narcissist finally facing consequences. They may write letters they’ll never send, filling pages with the fury they were never allowed to express. Some create rituals of release—burning wedding photos, smashing dishes that hold memories, screaming in their cars where no one can hear. This is healing and breakthrough.

Anger is essential to recovery from trauma, representing progress from the numbing and denial that initially protected the psyche. 546 The survivor who can feel anger has moved from ‘This is my fault’ to ‘This was done to me’. They have shifted from self-blame to accurate attribution of responsibility. The rage says: ‘I deserved better. What happened to me was wrong. I am worth defending’.

Yet expressing this rage safely requires support and often professional guidance. The survivor who has repressed anger for years may fear their rage will destroy them or others. They need safe containers—therapy, support groups, somatic practices—to discharge this energy without retraumatising themselves or alienating the support systems they desperately need. Rage held in the body must be discharged physically, not just processed cognitively, for healing to occur. 727

Stage 4: Reclaiming the Self—The Archaeology of Identity

After the acute crisis of leaving and the raw grief of early recovery comes a quieter but equally important phase: rediscovering who they are beyond the narcissist’s projections and demands. This is delicate archaeological work—sifting through the rubble of a demolished self to find what remains of the original person, what can be salvaged, what must be rebuilt entirely.

Rediscovering Preferences, Desires, and Boundaries

The survivor emerging from narcissistic abuse often discovers they no longer know their own preferences. After years of subordinating their needs to avoid narcissistic rage, of shapeshifting to match the narcissist’s ever-changing demands, simple questions become overwhelming. What do you want for dinner? What movie would you like to watch? What colour should you paint your bedroom? The narcissist’s voice, internalised after years of conditioning, provides automatic answers: “You are too picky about food.” “Your taste in movies is stupid.” “You have no eye for colour.”

Survivors in the Klein et al. study described this loss of self in vivid terms. One participant recalled standing in a supermarket, paralysed: “I literally didn’t know what I liked to eat anymore. For years, I bought what he wanted, cooked what he demanded, ate whatever wouldn’t trigger his criticism. Standing in front of the cereal aisle, I started crying because I couldn’t remember if I liked corn flakes or if that was him. It sounds so small, but it was everything—I had lost myself so completely that I didn’t even know my own taste in breakfast cereal.” 670 The researchers found this pattern repeatedly: most subjects reported feeling as though they had lost part of themselves, that their self-concept had “shrunken,” or that they’d become a “shell of themselves.”

Rebuilding begins with micro-decisions, tiny acts of self-determination. The survivor might spend weeks trying different foods, noticing what their body actually enjoys versus what they were told to like. They might visit stores alone, touching fabrics, noticing what feels good against their skin rather than what someone else deemed appropriate. They might listen to music they were forbidden or mocked for enjoying, letting their body respond without judgement. Each small preference recovered is a small piece of self reclaimed.

The Terror and Freedom of Authentic Choice

As preferences reemerge, the survivor faces the terrifying freedom of authentic choice. For years, perhaps decades, someone else dictated their reality. There was a perverse safety in that imprisonment—no responsibility for decisions, no risk of choosing wrong, no vulnerability of expressing authentic desire only to have it crushed. Now, every choice carries weight. Every decision could be wrong. Every expression of self risks rejection.

The anxiety can be paralysing. Survivors report standing in clothing stores, unable to choose because they can no longer hear the narcissist’s voice telling them what to wear, but have not yet recovered their own aesthetic sense. They sit in restaurants, unable to order because they are simultaneously free to choose anything and convinced every choice will be wrong. This is a normal response to the cognitive liberation that follows cognitive imprisonment.

Slowly, with support and practice, the survivor learns to tolerate the discomfort of choice. They learn that choosing “wrong”—picking a restaurant that turns out to be mediocre, buying a shirt they later dislike—is not catastrophic. These small failures, which would have brought narcissistic rage, now become data points in self-discovery. “I do not actually like sushi” becomes valuable self-knowledge rather than evidence of inadequacy.

The Role of Therapeutic Support

The deep rewiring required after narcissistic abuse often exceeds what survivors can accomplish alone. Traditional talk therapy, while valuable, frequently proves insufficient—the trauma lives not just in thoughts and emotions but in the body itself. Chronic muscle tension from years of hypervigilance, collapsed posture from perpetual shame, shallow breathing from always being braced for attack: these somatic patterns require specific interventions.

Fortunately, trauma treatment has evolved dramatically. Approaches like Somatic Experiencing Somatic Experiencing A body-based trauma therapy that works with physical sensations to release trapped survival energy and restore nervous system regulation. , EMDR EMDR Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing—a trauma therapy that uses bilateral stimulation to help process and integrate traumatic memories. , and internal family systems offer powerful pathways to healing that address the nervous system directly, not just cognition. These modalities are explored in depth in the next chapter, along with the broader therapeutic landscape and systemic changes needed to support survivors. For now, what matters is knowing that effective help exists—that the damage inflicted by narcissistic abuse, however deep, can be healed.

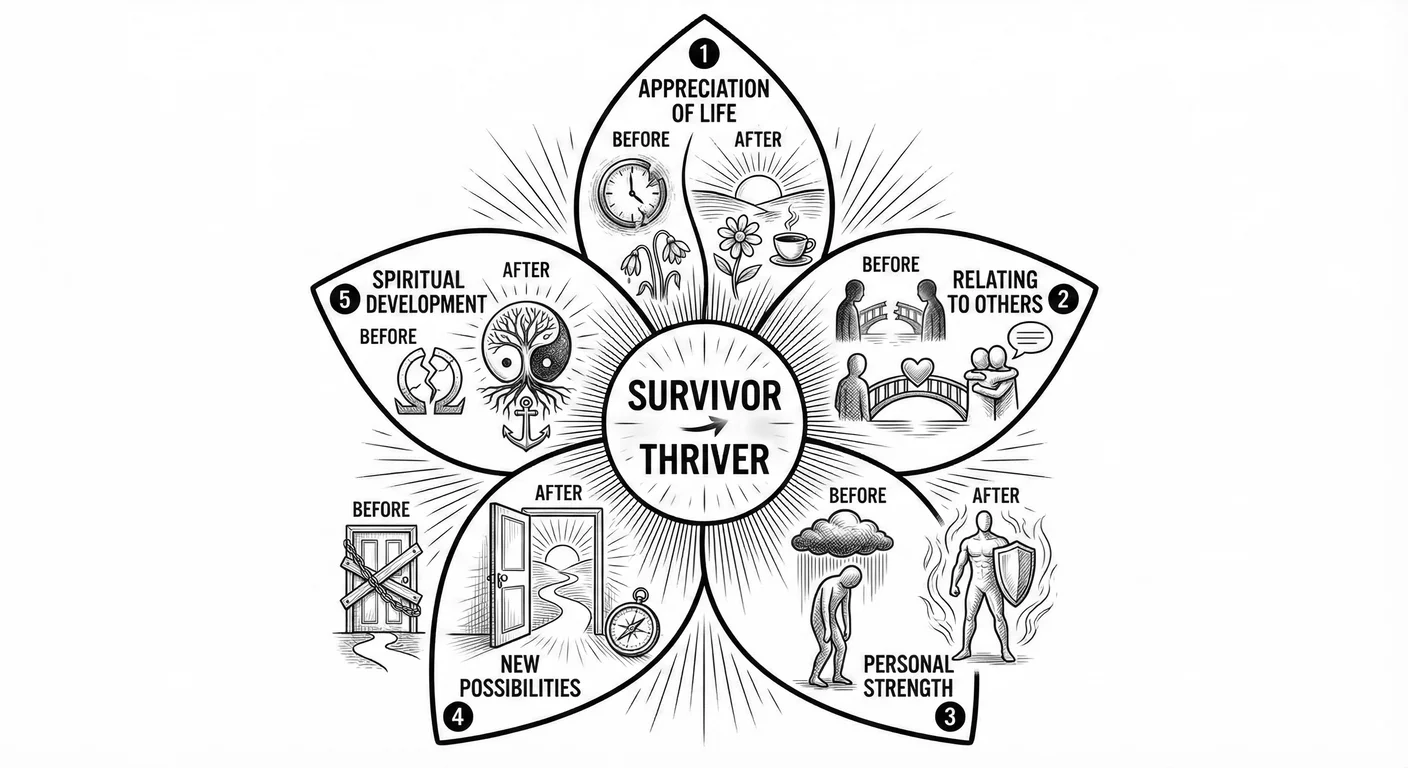

Stage 5: Post-Traumatic Growth—The Alchemy of Suffering

Not everyone who experiences trauma will experience post-traumatic growth, and there should be no pressure or expectation to find “silver linings” in abuse. But research consistently demonstrates that 50-70% of trauma survivors do report significant positive changes following their traumatic experiences—because of their struggle to survive and make sense of it, however terrible the trauma itself 1213 . For narcissistic abuse survivors, this growth often takes specific forms shaped by their particular journey through recovery.

The Five Domains of Growth

Tedeschi and Calhoun identified five areas where Post-Traumatic Growth Post-Traumatic Growth Positive psychological change experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging circumstances—finding meaning, strength, and transformation through adversity. commonly occurs:

Appreciation of Life: Survivors often report a marked shift in what matters. The small pleasures the narcissist mocked or forbade—a quiet morning with coffee, a walk in nature, a genuine conversation with a friend—become sources of deep joy. Having lived in chaos, peace becomes precious. Having been denied basic emotional nourishment, simple kindness feels miraculous.

Relating to Others: Paradoxically, betrayal by someone they trusted can lead to deeper, more authentic relationships with others. Survivors develop what one called “narcissist radar”—the ability to quickly identify manipulative people. More significantly, they develop deep appreciation for genuine connection. Having experienced false intimacy, they recognise and treasure the real thing.

Personal Strength: “If I survived that, I can survive anything” transforms into a common refrain. The survivor who extracted themselves from a narcissist’s web, rebuilt their life from nothing, and reclaimed their identity knows their own resilience in their bones. This is not naive optimism but tested confidence—they have been to hell and back and know they can handle whatever comes.

New Possibilities: Dreams the narcissist crushed often resurface with surprising vitality. The woman forbidden from returning to school enrolls in university at 50. The man whose creative pursuits were mocked publishes his poetry at 60. The entrepreneur whose business ideas were sabotaged launches a successful company at 45. Free from someone who needed them small, they discover how large they can become.

Spiritual/Existential Development: Many survivors report a spiritual awakening—sometimes religious, often a broader sense of meaning and connection. Having touched the depths of human cruelty, they often develop deep compassion. Having experienced systematic disconnection, they seek and create authentic connection. Having had meaning stripped away, they become architects of purpose.

From Victim to Survivor to Thriver

The journey from victim to survivor is often discussed, but the continued evolution to thriver is less acknowledged. A victim is in active danger, survival mode engaged, choices constrained by immediate threat. A survivor has achieved safety but remains organised around the trauma—healing from it, processing it, building defences against its recurrence. A thriver has integrated the experience into a larger life narrative and drawn power from it without being defined by it.

This evolution is not linear, and people may inhabit different stages simultaneously in different life areas. Someone might be thriving professionally while still surviving in intimate relationships. They might have healed from childhood narcissistic abuse but be actively victimised in their workplace. The stages are descriptive, not prescriptive—there is no timeline, no “should” about where someone needs to be in their journey.

Developing Earned Security

One of the most hopeful findings in attachment research is the phenomenon of “earned security.” While our early attachment experiences powerfully shape our relational patterns, they do not determine them irrevocably. Research indicates that 40% of people with insecure childhood attachments achieve earned security in adulthood—they develop the capacity for stable, secure relationships despite their traumatic beginnings 1046 .

For narcissistic abuse survivors, earned security requires three components: developing a coherent narrative that makes sense of what happened and why, emotional processing that allows feelings to be felt and integrated, and behavioural change through learning and practicing new relational patterns. The work involves metabolizing experience into wisdom, not “forgetting the past” or “moving on.”

The coherent narrative component explains why writing, whether in journals, therapy, or support groups, proves so powerful for survivors. The narcissist’s gaslighting created narrative incoherence—events that did not make sense, causality that did not track, a life story full of inexplicable gaps and contradictions. Creating a coherent narrative restores cognitive order. “He was not moody; he was manipulative.” “I was not too sensitive; I was being abused.” “The relationship did not fail; it was sabotaged.” Each clarification builds a story that makes sense, a self that coheres.

As survivors progress through their healing journey, often achieving remarkable growth and transformation, a painful question frequently emerges: “If I can change this much, why cannot they?” The next chapter addresses this question directly—examining why narcissists rarely change, what therapeutic resources exist for survivors, how to rebuild relationships after abuse, and what systemic changes are needed to create a world where narcissistic abuse is recognised, prevented, and healed.