We are the first generation to have to actively choose our level of engagement with the digital world. How we spend the next few years will decide whether technology will liberate us or enslave us.

— —Yuval Noah Harari

Introduction: The Digital Mirror Pool

In September 2022, Molly Russell’s father Ian held up his daughter’s iPhone at a coroner’s inquest in North London. The inquest had taken five years to reach this moment—five years of legal battles to access his daughter’s social media data. The phone was small, ordinary, the same model carried by millions of teenagers. But what it contained was not ordinary. In the six months before Molly took her own life in November 2017, she had viewed 16,300 pieces of content on Instagram and Pinterest. Of these, 2,100 related to suicide, self-harm, and hopelessness. She had generated a Pinterest board with 469 images on these themes, a digital scrapbook of despair that nobody knew existed until her family, after five years of legal battles with tech companies, finally gained access to her accounts.

The algorithm had noticed her interest. It had learned what kept her scrolling. And so it served her more. No one at Instagram or Pinterest wanted a fourteen-year-old girl to die. The system was simply optimised for engagement, and Molly’s engagement with dark content was measurable and monetisable. Pinterest sent her emails with subject lines like “10 depression pins you might like” and “new ideas for you in depression.” The machine was working exactly as designed.

Senior Coroner Andrew Walker ruled that Molly “died from an act of self-harm while suffering from depression and the negative effects of online content.” The coroner found that the online material “was not safe” and “shouldn’t have been available for a child to see.” It was the first time in legal history that social media was officially cited as a contributing factor in a child’s death. But Molly was not an anomaly. She was what the system produces when it finds a vulnerable mind and optimises for attention above all else.

For Molly, no one saw the warning signs. Her Pinterest board of 469 depression images existed in a space her parents could not access, curated by an algorithm that understood her engagement patterns better than anyone who loved her. The coroner’s inquest revealed that Molly’s family had no idea what she was consuming; the platforms were designed to be opaque to parents while being transparent to advertisers. This opacity is not accidental. It is the business model.

Opacity, however, can be pierced. Patterns can be recognised. The difference between a child building a palace and a child lost in a maze manifests in observable behaviours and emotional responses. The same is true for adults, for relationships, for institutions. You cannot protect what you cannot see. You cannot escape a maze you do not know you are in.

Molly’s story exemplifies the darkest endpoint of a phenomenon transforming human psychology at unprecedented speed: the weaponisation of our deepest psychological vulnerabilities by digital platforms designed to exploit them for profit. Dr Sherry Turkle 1248 , a clinical psychologist and MIT professor, has been studying human-technology interaction since the early days of personal computing. What she observed beginning in the late 2000s alarmed her: a deep shift in how humans understand connection and selfhood. She called it “alone together”, a paradox where we are more connected yet lonelier than ever, performing elaborate versions of ourselves while losing touch with who we actually are.

“We expect more from technology and less from each other,” Turkle writes. “We are lonely but fearful of intimacy…\ Digital connections offer the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship.”

Digital technology acts as a great accelerant, finding existing vulnerabilities and amplifying them exponentially. The unseen children—hungry for recognition and validation their parents never provided—find in social media a machine that promises unlimited mirroring while delivering only deeper invisibility. The narcissistically injured, seeking the perfect reflection Narcissus sought in his pool, find instead infinite screens that multiply their image while fragmenting their identity.

The Smartphone as Abusive Parent

Chapter identified five mechanisms by which proximity to a narcissist reshapes the brain: chronic stress dysregulation, attachment system conditioning, mirror system atrophy, prefrontal hijacking, and default mode network disruption. The smartphone activates every single one.

[style=nextline,leftmargin=1.5em]

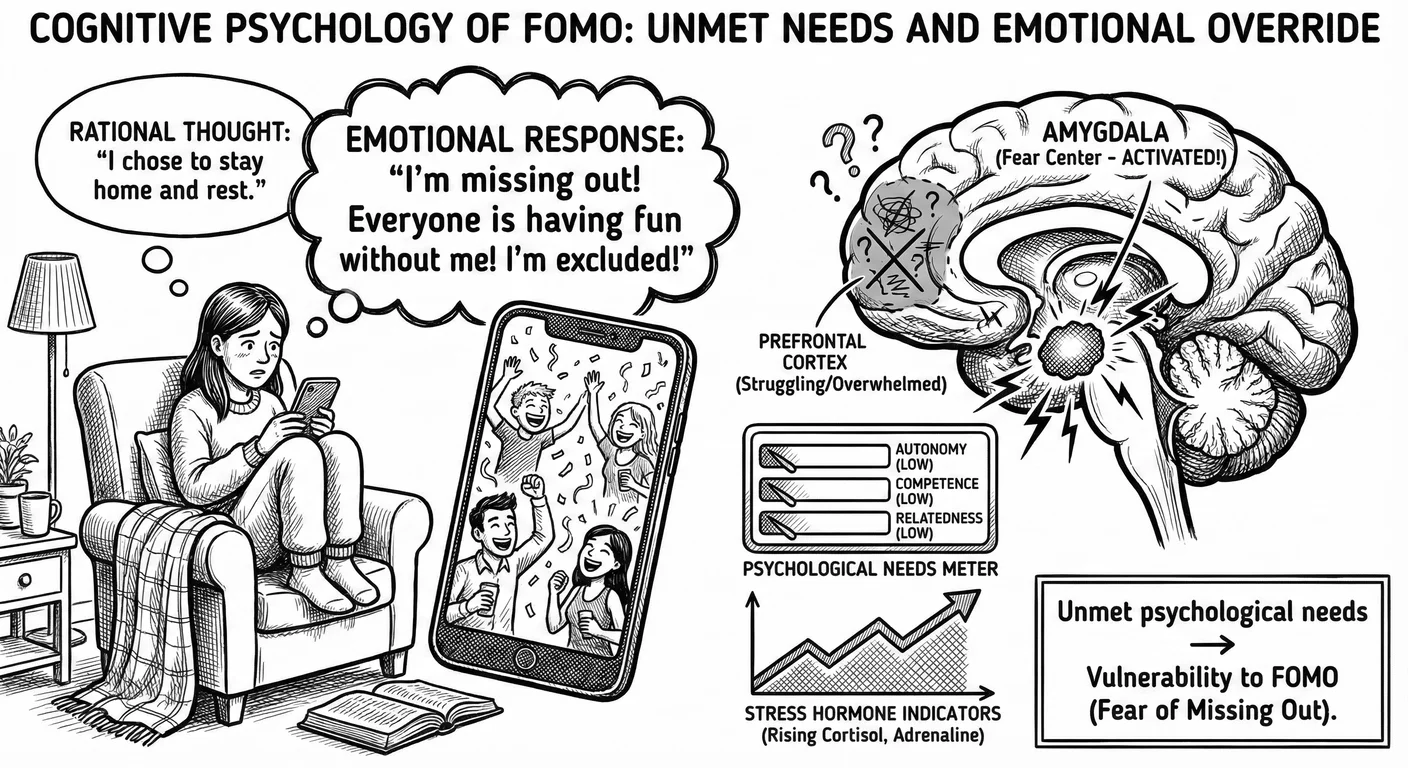

Chronic stress and HPA axis dysregulation: The notification ping triggers cortisol release. Social comparison on Instagram activates threat-detection circuits. FOMO (fear of missing out) maintains low-grade anxiety. The phone creates what narcissistic abuse creates: an environment of chronic, unpredictable stress where the next emotional assault—a hurtful comment, an unflattering tagged photo, evidence of exclusion—could arrive at any moment.

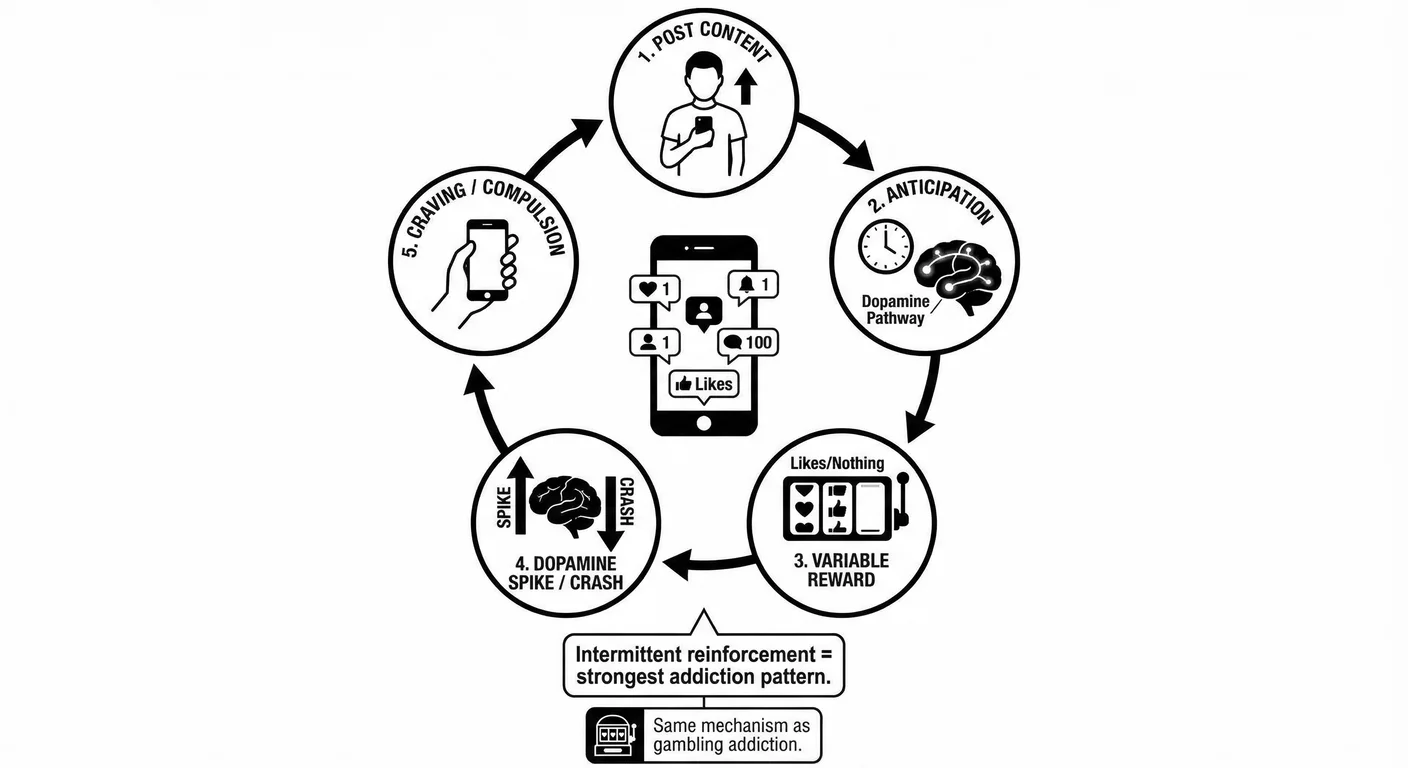

Attachment system conditioning: The intermittent reinforcement that bonds victims to abusers operates identically through likes and notifications. Sometimes your post goes viral; usually it doesn’t. Sometimes the notification brings validation; sometimes rejection. The unpredictable reward schedule that Chapter identified as creating addiction-like attachment to narcissists is the explicit design principle of social media platforms.

Mirror system atrophy: A screen cannot mirror your emotional state. It cannot attune to your distress and respond with comfort. The hours spent seeking connection through devices that cannot provide reciprocal emotional mirroring produce the same deficit that develops in children whose narcissistic parents never reflected them back to themselves.

Prefrontal hijacking: The constant pull of notifications redirects executive function from self-directed goals to phone-checking, exactly as living with a narcissist redirects cognitive resources to threat-monitoring. Studies show the mere presence of a smartphone—even turned off—reduces available cognitive capacity. 1297 The prefrontal cortex, perpetually managing digital demands, cannot fully engage with present experience or long-term planning.

Default mode network disruption: The DMN activates during rest, enabling self-reflection and memory consolidation. Endless scrolling prevents this restorative function—there is no “rest” when a bottomless feed awaits. Heavy smartphone users show reduced DMN connectivity, 760 the same pattern observed in those living under chronic narcissistic stress.

This is not analogy. It is mechanism. The smartphone does not merely resemble an abusive relationship; it exploits identical neural pathways through identical psychological techniques. The platforms employ neuroscientists specifically to optimise these effects. The correlation between smartphone adoption and rising mental health concerns reflects causation operating through documented, replicable mechanisms—the same mechanisms that make narcissistic relationships neurologically devastating.

The difference is scale. A narcissistic parent damages one child. A narcissistic partner damages one family. A smartphone in every pocket, running algorithms optimised for engagement above all else, damages an entire generation. The neuroplasticity of proximity has gone viral.

The relationship between social media and narcissistic patterns is engineered, hardly coincidental. As whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed in her October 2021 testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee—after disclosing tens of thousands of Facebook’s internal documents—social media companies deliberately design their platforms to exploit psychological vulnerabilities. They employ teams of neuroscientists and behavioural psychologists whose explicit goal is to maximise “engagement”, a euphemism for behavioural addiction. The techniques they use— Intermittent Reinforcement Intermittent Reinforcement An unpredictable pattern of rewards and punishments that creates powerful psychological dependency, making abusive relationships extremely difficult to leave. and social comparison—are precisely those that activate and exacerbate narcissistic defences.

Longitudinal analysis of data from 11 million young people documented increasing rates of depression and suicide among teenagers—rising by more than 50% between 2010 and 2015, precisely the period when smartphones became ubiquitous and social media use exploded. 1255 This is not merely correlation; dose-dependent relationships emerged: the more time teenagers spend on social media, the more likely they are to report symptoms of depression and anxiety.

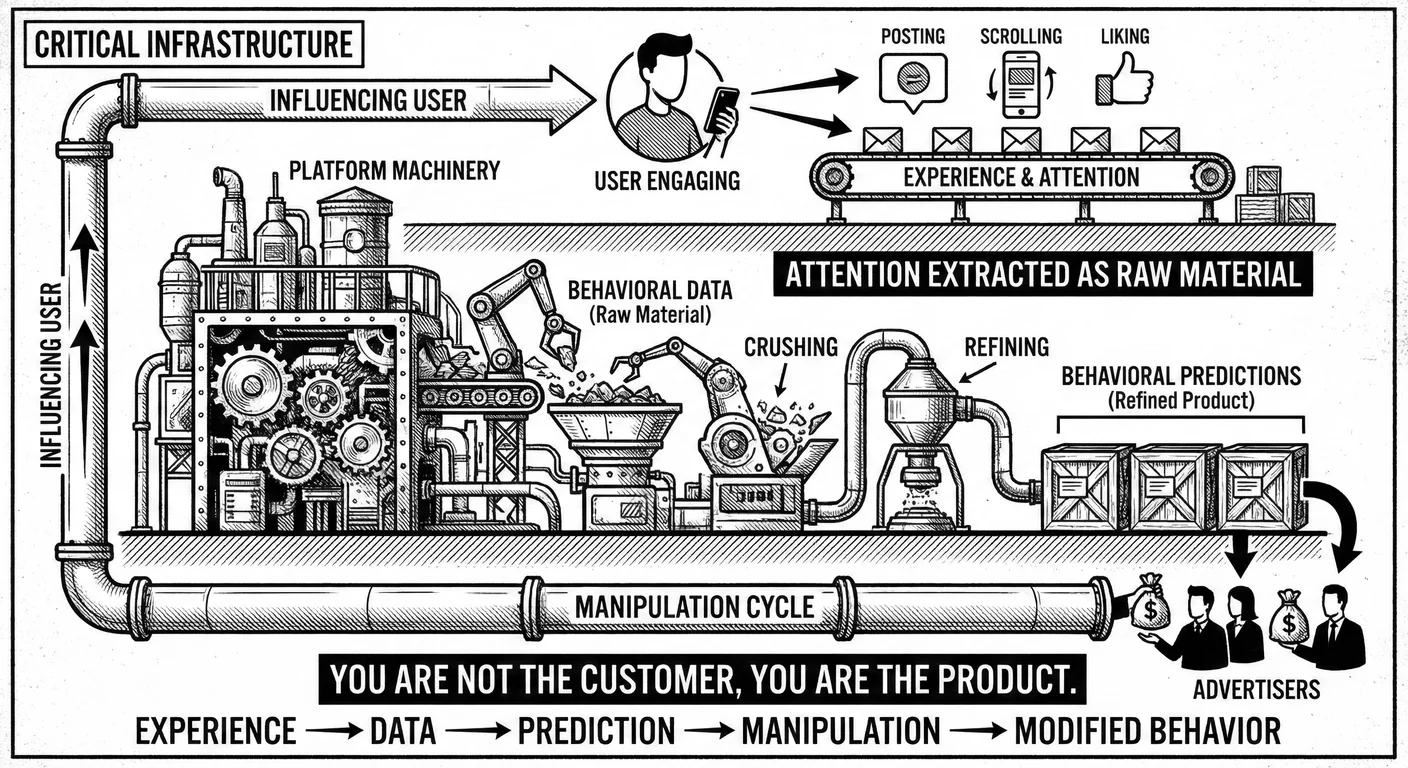

The impact extends far beyond mental health statistics. Social media is altering how humans develop identity and perceive reality itself. 1372 This is ‘surveillance capitalism’—the unilateral claiming of private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data sold into behavioural futures markets, pioneered by Google and Facebook—an economic system that extracts human behaviour as raw material for predictive products. In this system, we are the product, our attention and data harvested and sold, while advertisers are the customers. More disturbingly, our very selves become products—personal branding marketed for likes and engagement.

Digital platforms provide infinite mirrors—every screen a potential reflection, every platform a stage for performance. They quantify self-worth through metrics—likes and followers—creating a numerical hierarchy of human value. They enable perfect curation of self-image through filters and selective presentation. They deliver Intermittent Reinforcement Intermittent Reinforcement An unpredictable pattern of rewards and punishments that creates powerful psychological dependency, making abusive relationships extremely difficult to leave. —unpredictable rewards that create addiction-like dependence upon external validation. They allow for the complete commodification of human relationships and experience.

The grandiose false self (detailed in Chapter 1) finds perfect expression in curated profiles and filtered selfies. The need for validation (explored in Chapter 1’s discussion of supply economy) is fed by likes and comments, though never satisfied. The tendency towards idealisation and devaluation is amplified by the ease of following and unfollowing. The empathy deficit established in Chapter 1—emotional empathy impaired while cognitive empathy remains intact—finds enablement in the distance and anonymity of digital interaction. The rage at narcissistic injury finds outlet in cancel culture and viral shaming.

More troubling still, social media does not simply amplify existing narcissistic traits; it actively creates them in previously healthy individuals. Teenagers who use Facebook more often show more narcissistic tendencies, and young adults who have a strong Facebook presence show more signs of psychological disorders including Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) A mental health condition characterised by an inflated sense of self-importance, need for excessive admiration, and lack of empathy for others. . 1057 The platforms are literally training users to become more narcissistic, rewarding self-promotion and the commodification of experience.

The tragedy is that those most vulnerable to social media’s narcissistic amplification are those already wounded by narcissistic abuse. The adult children of narcissists explored in Chapter , desperate for the validation they never received, are particularly susceptible to social media’s false promises. The platforms exploit the same psychological mechanisms their parents did—intermittent reinforcement and devaluation—but at industrial scale and algorithmic efficiency.

This digital acceleration has realised Christopher Lasch’s warning about a culture of narcissism where the pathological becomes normal. The mass performance of self erodes the distinction between performer and audience. Compulsive documentation colonises private life. Metric-based worth displaces intrinsic value. Commodified connection reshapes intimacy.

Technology is not neutral. The platforms are designed with specific goals—maximising engagement and advertising revenue—that directly conflict with human wellbeing. The fact that they damage mental health and amplify narcissistic traits is a feature, designed in from the start. The business model depends on creating and maintaining the very wounds they claim to heal.

Digital Mirrors Everywhere

The Quantification of Self-Worth

In 2009, when Facebook introduced the ‘like’ button, they altered human social interaction. What seemed like a simple feature, a quick way to show appreciation for content, transformed into a mechanism for the complete quantification of social contingent self-esteem. Within a decade, metrics of engagement would become the primary currency of self-worth for billions of people, creating what Dr Gwendolyn Seidman 1114 calls ‘the quantified self’: an identity determined by numerical feedback rather than intrinsic qualities or genuine relationships.

Every post becomes a referendum on one’s value; every photo carries the anxiety of potential rejection; every shared thought risks the humiliation of silence. How many likes? How many followers? How many views? These metrics, meaningless in any real sense, become the measures by which people judge their worth and place in the social hierarchy.

Social media likes trigger dopamine release in the same reward pathways activated by gambling and cocaine (see Chapter for detailed neurobiology). 1133 Neuroimaging confirms these effects extend to brain structure: heavy social media users show grey matter alterations in addiction-related regions identical to those seen in substance dependence, 536 while media multitasking correlates with reduced grey matter density in the anterior cingulate cortex—a region critical for emotional regulation and empathy. 761 The platforms have generated a digital drug, with likes as the dose and the smartphone as the delivery mechanism. The same circuitry, disturbingly, works in reverse: Molly Russell scrolled through depression content because despair, like joy, is engaging, and the algorithm cannot distinguish between engagement that heals and engagement that destroys.

Algorithmic manipulation adds another layer. Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, and other platforms do not show content chronologically but through algorithms designed to maximise engagement. They learn what triggers response—primarily outrage—and serve content accordingly. Technology critic Jaron Lanier 708 calls this ‘continuous behaviour modification on a mass scale’. Users are not just seeking validation; the platforms train them to seek it in ways that serve platform interests.

The platforms deliberately exploit the psychological principle of intermittent reinforcement, which B.F. Skinner identified as the most powerful mechanism for creating persistent behaviour. You never know when you will get the reward of viral content or high engagement, so you keep checking, posting, refreshing. Dr Adam Alter 26 calls this unpredictability ‘behavioural addiction’—compulsive engagement despite negative consequences. Industry research found that the average person checks their phone 96 times per day, often unconsciously, seeking the next hit of digital validation. 55

The Skinner Box reimagined: social media’s addiction cycle. Post content, receive variable rewards (likes or silence), experience dopamine spike or crash, feel anxiety and craving, post more. The same intermittent reinforcement that Skinner discovered creates compulsive behaviour in laboratory animals now operates at civilisational scale.

Quantification extends beyond simple likes to complex hierarchies of digital status. Blue checkmarks indicate “verified” accounts, creating a caste system of credibility. Follower counts determine influence and access to opportunities. Engagement rates affect visibility through mysterious algorithms. A new social stratification has emerged, based entirely on digital metrics—what researcher Alice Marwick 803 calls ‘the influencer economy’, where human value is literally calculated by engagement rates and follower counts.

The Selfie as Modern Narcissus

The selfie exemplifies the perfect crystallisation of digital narcissism: the self as both subject and object, photographer and photographed. Like Narcissus gazing into his pool, the selfie-taker stares into the screen, seeking the perfect reflection. But unlike Narcissus, who saw only one image, the digital self can take hundreds of photos—selecting and editing until the image matches an impossible ideal.

Industry estimates suggest that 93 million selfies are taken globally per day, with the average person taking over 25,000 in a lifetime. 720 By age seven, the average child has already appeared in approximately 1,500 photos shared on social media. We have become a species obsessed with self-documentation, turning every experience into an opportunity for self-portraiture.

Dr Jesse Fox’s research at Ohio State University found direct correlations between selfie-posting frequency and narcissistic traits. 412 Fox and Rooney’s study of 800 men found that those who posted more selfies scored higher on narcissism and psychopathy, with those who edited selfies scoring higher on narcissism and self-objectification. Follow-up research found similar patterns in women. The act of taking and sharing selfies does not just reflect narcissistic traits; it cultivates them, training the brain to see the self as an object for display and evaluation.

The phenomenon of ‘Snapchat selfie dysmorphia’—a form of body dysmorphic disorder where patients seek plastic surgery to replicate their filtered selfies—identified by dermatologists at Boston University, 1275 reveals the severe psychological impact of filtered self-images. Patients increasingly bring filtered selfies to plastic surgeons, asking to look like their digitally altered selves. The filters—which enlarge eyes and reshape faces—create impossible beauty standards that users internalise as achievable goals. A 2022 survey found 79% of plastic surgeons reported patients wanting to look better in selfies. 1 The line between real and digital self blurs, with devastating consequences for self-perception and mental health.

Death by selfie has become a genuine public health concern: research published in the Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 75 documented 259 selfie-related deaths between 2011 and 2017—people falling off cliffs or being hit by trains, all while trying to capture the perfect self-image. The Russian government has launched a “Safe Selfie” campaign. The literal danger of selfie-taking serves as a dark metaphor for its psychological dangers: the destruction of self through obsessive self-focus.

Dr Renee Engeln’s 359 research on ‘beauty sick’ culture reveals how selfie culture particularly damages young women. The constant self-scrutiny and reduction of self to appearance produces “self-objectification”, seeing oneself from an outsider’s perspective rather than experiencing life from within. This external focus correlates with increased rates of depression and eating disorders. When attention is focused on appearance, fewer cognitive resources remain for other tasks.

The selfie also embodies a deep shift in how we experience life. Dr Susan Greenfield 490 , a neuroscientist at Oxford, warns that constant self-documentation prevents full engagement with experience. Instead of living moments, we perform them. Instead of seeing sights, we photograph ourselves in front of them. The selfie stick, extending the arm to fit more background into the self-portrait, perfectly symbolises this distancing from direct experience—life held at arm’s length, mediated by the screen.

Sophie, nineteen, shows me her camera roll. We are in a coffee shop near her university in Manchester, and she scrolls through what looks like the same photo repeated hundreds of times. “This was one lunch,” she says. “I took 147 photos trying to get one I could post.” She zooms in on her face in each rejected image, pointing out flaws invisible to me: jawline wrong, eyes too small, skin texture visible. The photo she eventually posted—after forty minutes of editing—shows a smiling girl enjoying avocado toast. “I didn’t even eat it,” she admits. “It went cold. I wasn’t hungry anymore anyway.” She has 3,200 followers. Her therapist has diagnosed body dysmorphic disorder. “I know what I look like in real life doesn’t matter as much as what I look like online. That’s where people actually see me. The real me is just… draft content.”

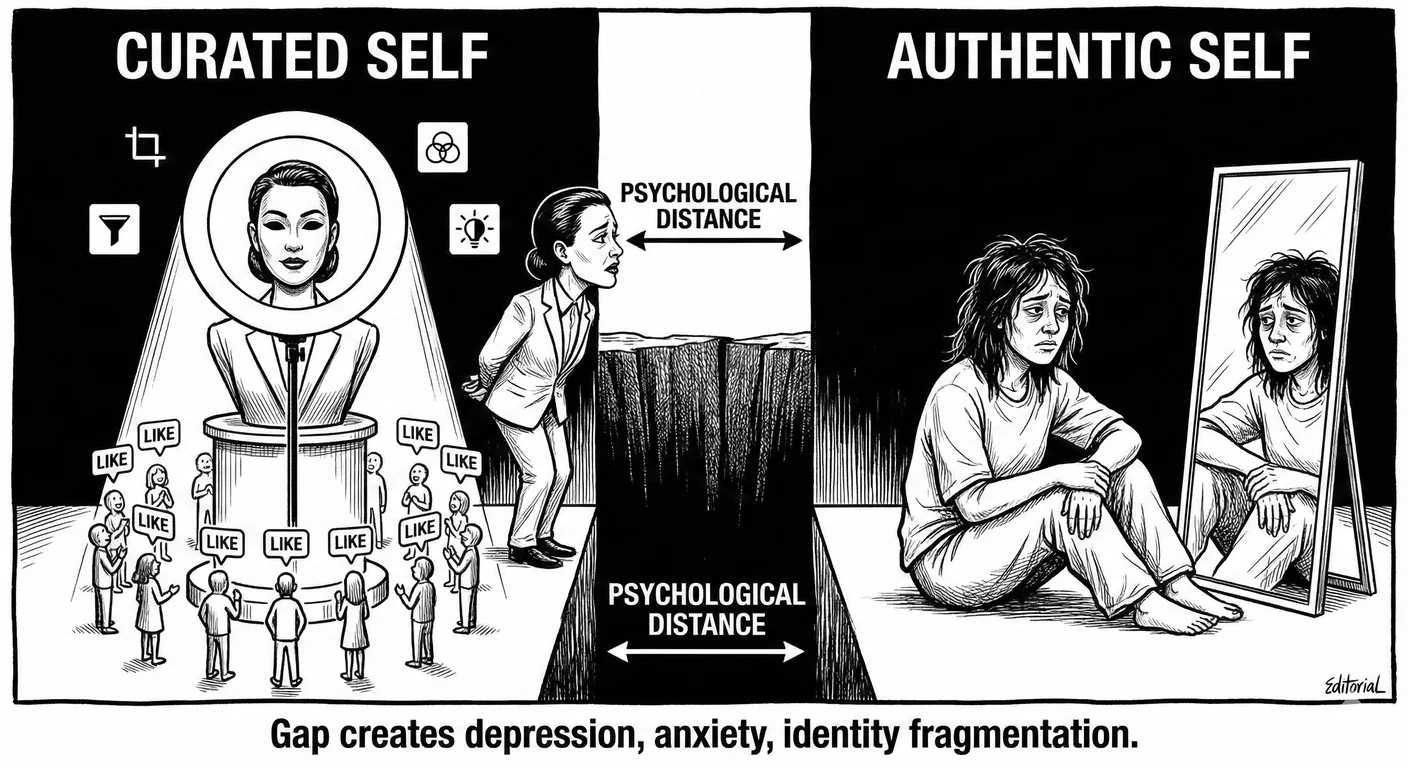

The Curated Self vs. Authentic Self

Social media profiles represent the ultimate expression of the False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. , but unlike the false self developed in response to narcissistic parenting, the digital false self is conscious and constantly refined based on algorithmic feedback. We have become curators of our own lives, selecting and editing experience to create idealised narratives of who we wish to be.

The labour involved in this curation is exhausting yet invisible. Ethnographic work with social media users 803 exposed the intense work behind seemingly casual posts. Users report spending hours selecting photos and timing posts for maximum engagement. They maintain spreadsheets tracking metrics, use multiple apps for editing and scheduling, and constantly monitor competitors’ content. The “influencer” who appears effortlessly perfect is actually engaged in full-time identity construction.

The gap between curated online self and lived reality produces ‘the authenticity paradox’. Users know their own profiles are carefully constructed performances, yet often believe others’ presentations are genuine. Impossible standards and constant inadequacy follow. Comparing internal experience to others’ curated external presentations predictably decreases self-esteem and increases depression. 190

Multiplying selves across platforms adds another layer of complexity. Users maintain different personas on LinkedIn, Instagram, and TikTok (the professional self, the party self), all performed simultaneously, often contradictorily. This identity diffusion—maintaining multiple contradictory self-presentations without a coherent core identity—is what Turkle calls ‘the tethered self.’ It prevents the integration necessary for psychological health.

Logging off from these curated selves becomes impossible, creating chronic anxiety. Unlike previous generations who could leave false selves at work or social events, digital natives carry their performed identities constantly. The profile exists 24/7, accumulating likes and judgements even while sleeping. Fear of missing out (FOMO) keeps users constantly connected, unable to risk the social death of digital absence.

Platform design deliberately makes authentic self-expression risky while rewarding performance. The algorithmic prioritisation of engaging content means that extreme presentations, whether perfect or disastrous, get more visibility than ordinary life. The ‘Instagram vs. Reality’ movement, showing the difference between posted photos and actual circumstances, reveals the extent of this distortion but has not changed behaviour. Users know the game is rigged but feel compelled to play anyway.

Tom, twenty-four, works in marketing but spends more time on his personal brand than his job. We meet in a co-working space in Shoreditch where he is photographing his laptop and coffee for LinkedIn. “I post three times a day minimum,” he explains, adjusting the angle. “Morning motivation, lunchtime insight, evening reflection. I have a content calendar. I batch-produce posts on Sundays.” His feed shows a confident young professional: keynote speeches, networking events, thought leadership. “Most of it’s exaggerated,” he says quietly. “That keynote was a five-minute slot at a free meetup. The networking photos are from the same three events, just cropped differently.” He pauses. “The worst part is I’ve done this so long I don’t know what I actually think anymore. My opinions are whatever gets engagement. I’m a character I invented, and I can’t remember who I was before him.”

The Addiction Machine

Social media platforms deliberately exploit intermittent reinforcement—the same mechanism that creates trauma bonding in narcissistic families (Chapter ). Tech companies employ ‘attention engineers’ using casino techniques: the pull-to-refresh gesture, the notification sounds—all designed to trigger compulsive checking. 26 Former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris, founder of the Centre for Humane Technology, has exposed how these features deliberately ‘hijack our minds.’

The neurobiological impact is measurable: heavy users display grey matter changes in addiction-related regions identical to substance addiction. 536 Notably, these changes extend to prefrontal regions responsible for impulse control: Facebook users show impaired inhibitory systems in the same amygdala-striatal circuitry that governs self-regulation, 1247 while smartphone-based social media use correlates with altered grey matter volume in the nucleus accumbens. 885 The intermittent schedule produces what gambling researcher Dr Natasha Schüll calls ‘the zone’—a dissociative state characterised by loss of time awareness and compulsive continuation despite exhaustion—users scrolling for hours without conscious awareness, unable to stop.

The Attention Marketplace

In what Dr Michael Goldhaber 462 presciently called the ‘ attention economy ’—theorising in 1997 that the global economy was shifting from material-based to attention-based, since information is not scarce but attention is inherently limited—human attention has become the scarcest commodity. Social media platforms are attention-harvesting machines, extracting this resource and selling it to advertisers. But users have internalised this economy, competing desperately for scarce attention, turning themselves into content producers in an endless battle for visibility.

Dr Zygmunt Bauman 87 calls this ‘liquid modern life’—nothing is stable, and individuals must constantly market themselves to avoid irrelevance. Every user transforms into an entrepreneur of the self, building “personal branding,” tracking “engagement metrics.” Market language has colonised personal expression, turning human connection into transactional exchange.

The mechanics are not new—only the scale. Twentieth-century personality cults pioneered what social media has perfected: the systematic manufacture of validation as a state obligation. Under Stalin, towns and streets bore his name; citizens competed to compose hymns to his genius; children were taught to thank ‘Father Stalin’ for their happiness. 162 The ideology mandated continuous displays of devotion—mandatory rallies, public pledges, ritual denunciations. What required secret police to enforce in the twentieth century, social media has achieved through gamification in the twenty-first. The difference: where totalitarian systems demanded validation of a single leader, digital platforms have democratised the dynamic, creating millions of micro-dictators each requiring their own tribute of likes and follows.

The influencer phenomenon exemplifies the full professionalisation of this self-commodification. According to Business Insider 181 , the influencer marketing industry is worth $13.8 billion. But the influencer dream sells a false promise. Dr Brooke Erin Duffy’s 335 research on ‘aspirational labour’—unpaid work performed in hope of future success, endemic to social media where millions create free content hoping to ‘make it’—reveals that for every successful influencer, thousands work for free, investing time and emotional labour into followings that will never monetise. The platforms profit from this free content while users bear all the risk.

The algorithms amplify content that generates strong emotional responses: outrage, envy, disgust, desire. Users learn to perform increasingly extreme versions of themselves. The reasonable and moderate are invisible; the outrageous and controversial thrive. Jaron Lanier 708 calls this ‘algorithmic behaviour modification’—users unconsciously adapting their personalities to what the algorithm rewards.

The Micro-Celebrity Trap

The democratisation of fame has created what Dr Alice Marwick 803 calls ‘the micro-celebrity’—ordinary people famous primarily for performing their lives online rather than for specific talents, embodying a shift in how humans understand identity and social value. Survey research suggests that 86% of young Americans would like to become influencers 890 —in a digital culture where visibility equals value, to be unseen is to be worthless.

Jessica, twenty-six, has 50,000 Instagram followers. She works as a personal trainer at a gym in Bristol, where we meet between her morning clients. The gym is empty at 10 AM, machines gleaming, mirrors reflecting mirrors. She is wearing the athleisure she’ll photograph for tonight’s content, but in person she looks tired, smaller than her profile suggests. “I started posting fitness content in 2019 to document my recovery after I got through anorexia. Ironic, right? I thought it would help me stay accountable. But once I started gaining followers, everything changed.” She demonstrates a bicep curl, her form perfect, her face switching instantly to the performance smile she uses in videos. “I can’t just work out anymore. I have to film it, edit it in CapCut, write a caption that sounds motivational but not preachy, post it at exactly 6:30 PM when my analytics say engagement peaks. I can’t eat a meal without considering how it photographs—do you know how many times I’ve let food go cold for the right angle?” The smile drops. “I transformed into a character called ‘FitJess’ who’s always motivated, always positive, always in a crop top with a flat stomach. The real me, who sometimes binges on Cadbury’s, who skipped the gym three times last week, who takes sertraline for depression—she had to disappear. I was playing myself in the movie of my life, and I couldn’t break character. Because when I tried, the numbers dropped, and without the numbers…” She gestures at the empty gym. “This job depends on the brand. No brand, no clients. No clients, no flat. I built my own cage.” Her experience mirrors the grandiosity as defence mechanism described in Chapter 1, the performed perfection masking deep vulnerability, the false self that becomes indispensable for survival.

The path to micro-celebrity reinforces narcissistic adaptations. Aspiring influencers develop a “niche”—a specific identity that distinguishes them. They consistently perform this identity regardless of authentic feelings. Every moment becomes potential content, every interaction possible engagement. The structure does not just attract people with narcissistic traits; it actively creates them. Longitudinal research 831 found that people who use social media more frequently become more narcissistic over time; the platforms are literally training users to develop narcissistic adaptations as survival strategies.

The greatest paradox is the performance of authenticity. As audiences have become savvy to fake perfection, influencers now perform ‘realness’—carefully curated vulnerability that appears spontaneous but is actually strategic. The ‘crying selfie’ phenomenon exemplifies this: influencers post photos of themselves crying, ostensibly to show vulnerability, but the act of stopping mid-breakdown to position the camera reveals the performance underneath. Even genuine emotion becomes content. The line between experiencing feelings and performing them dissolves.

The collapse when the audience disappears reveals the extent of narcissistic dependency. Interviews with former influencers describe experiences resembling withdrawal from addiction. Without constant validation, they experience emptiness and identity crisis. Having externalised their self-worth into metrics, they have no internal resources when the numbers disappear. Some describe feeling like they have ceased to exist.

The Scarcity Engine

The platforms manufacture anxiety through artificial scarcity. Despite unlimited potential for content, the zero-sum dynamics mean that attention given to one person is attention denied to another. But the psychological mechanism runs deeper than simple competition. Dr Andrew Przybylski and colleagues’ 2013 study 1010 delivered the first rigorous analysis of what they called ‘fear of missing out’ (FOMO), defined as ‘a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent.’

Przybylski’s research, grounded in self-determination theory, revealed something important: FOMO is not simply a personality trait or bad habit. It emerges from unmet psychological needs. Individuals who reported less satisfaction of their basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness also reported higher levels of FOMO. The fear is not irrational—it reflects genuine psychological hunger. Social media does not create this hunger, but it exploits it relentlessly, offering the appearance of relatedness while delivering only its simulation. Passive social media use—scrolling without posting—elevates cortisol levels, 113 producing the same HPA axis activation pattern observed in children with insecure attachment. The stress response that should be buffered by secure relationships is instead chronically triggered by algorithmic feeds designed to maximise anxiety-driven engagement.

The behavioural consequences are measurable. In Przybylski’s nationally representative sample of 2,079 adults, those high in FOMO were significantly more likely to check social media while driving and immediately upon waking. They reported ambivalent feelings towards social media—knowing it was bad for them but unable to stop. The pattern mirrors addiction precisely: awareness of harm combined with compulsive continuation.

Consider what FOMO actually feels like from the inside. It is 11 PM on a Friday and you are home, tired, wanting nothing more than sleep. You open Instagram. Stories from a party. Friends laughing. Someone you like talking to someone else. The rational mind knows this is a curated highlight, knows you chose to stay home, knows the party is probably awkward and loud. None of this matters. The gut clenches. The mood darkens. Sleep becomes impossible. You scroll, looking for—what? Evidence that you made the right choice? You will not find it. The algorithm ensures you see only what triggers engagement, and envy engages more reliably than contentment.

Now multiply this by every waking hour. The platforms provide constant windows into others’ curated lives, manufacturing the impression that everyone else is living better and succeeding more. Dr Bren’e Brown 167 calls this ‘scarcity mindset’: the belief that there is never enough, that someone else’s gain is your loss. Scarcity mindset was once an occasional visitor during genuinely competitive situations; social media now makes it ambient, inescapable, the baseline condition of digital existence.

The obsessive monitoring becomes automatic. Who viewed my story? Who unfollowed me? Whose post got more likes? The platforms provide detailed analytics enabling this surveillance, turning friendship into competition and connection into scorekeeping. Instagram’s ‘activity status’ shows exactly when someone was last online; users check to see if partners are active late at night, if friends are ignoring their messages, if crushes are looking at others’ profiles. The tools designed ostensibly for ‘staying connected’ become instruments of paranoid vigilance.

Children are increasingly treated as content in this marketplace. Family vloggers monetise their children’s lives from birth, creating what Dr Crystal Abidin 4 calls ‘micro-microcelebrity’—children famous for being their parents’ children. Consider the DaddyOFive scandal of 2017, where parents ‘pranked’ their children with psychological abuse for YouTube views, or the more recent expos’es of family channels where children describe being forced to perform emotions on camera, crying real tears while parents adjust lighting. These children grow up under constant surveillance, developmental moments transformed into monetised content. They learn that their worth lies in how many views they generate, divorced from who they are. Such cases exemplify malignant narcissism (discussed in Chapter 2): the combination of narcissistic grandiosity with antisocial behaviour and sadism, where pleasure is derived from others’ suffering while maintaining a public image of devoted parenting.

Molly Russell’s Pinterest board of 469 depression images exemplifies the dark inverse of this dynamic: a child whose algorithm-curated content was not monetised but was just as systematically optimised for engagement. The same system that rewards family vloggers for exploiting their children’s joy rewarded Pinterest for feeding Molly content about suicide. Both optimise for the same metric: time on platform. Both are indifferent to the human cost.

Dr Deborah Chambers 226 warns we are raising a generation for whom narcissistic self-commodification is normal development, indistinguishable from pathology. When children grow up seeing parents document every moment for likes, when their own childhoods exist primarily as content, when their developing sense of self must compete with algorithmic metrics from the earliest age, what inner architecture can possibly form? The palace requires private space and experiences that belong to oneself alone. The children raised in this fishbowl have no such space. Their palaces are glass.

Intimacy Commodified

Dating apps extend the same dynamics into our most intimate relationships. Over 300 million people now swipe through human beings reduced to photos and bullet points, making split-second judgements about worth. 182 Industry data suggests that the average dating app user swipes through thousands of profiles before meeting someone in person. Dr Barry Schwartz 1107 calls this ‘choice overload’—why work through relationship challenges when thousands of alternatives are at your fingertips? Users develop ‘relationship shopping’, approaching partners with a consumer mindset, never fully committing.

Priya, twenty-eight, has been on dating apps for six years. She is a solicitor in Birmingham, precise and articulate, but when she talks about dating her composure cracks. “I’ve been on maybe three hundred first dates,” she says. “Maybe more. I stopped counting.” She shows me her phone: Hinge, Bumble, Tinder, all active simultaneously. “I swipe while I’m in court, waiting for cases. On the train. In bed. It’s compulsive.” She describes the pattern: match, message, meet, disappointment, repeat. “Nobody’s ever good enough because I know there are thousands more options. Why settle? But then years pass and you realise you’ve optimised yourself out of any real connection.” She looks at her phone, then puts it face-down. “I’ve ghosted probably a hundred people. Been ghosted as many times. It doesn’t even feel cruel anymore—it’s just efficient. But I remember when someone not calling back would devastate me. Now I feel nothing. I’ve trained myself to feel nothing. And I’m not sure I can untrain it.”

‘ Ghosting Ghosting Abruptly ending a relationship by cutting off all communication without explanation. In narcissistic abuse, ghosting is often used as a discard tactic or punishment—leaving the victim confused, anxious, and desperate for closure that never comes. ’—abruptly ending all communication without explanation—has become endemic, with 65% of dating app users having experienced it. 1227 This behaviour normalises disposal without closure, reflecting narcissistic patterns of idealisation and devaluation. People become disposable commodities, discarded the moment they fail to meet expectations. Dr Lisa Wade 1284 found that ‘hookup culture’ surrounding dating apps—with its emphasis on emotional detachment and performance—teaches young people to suppress attachment needs and treat intimacy as achievement rather than connection. These patterns become templates for future relationships.

The algorithmic design of dating apps actively promotes these dynamics. Tinder’s original creators deliberately modelled the swipe mechanism on slot machines, exploiting the same variable reward schedules that make gambling addictive. 1076 The endless scroll of potential partners triggers dopamine release not through connection but through possibility—the next swipe might be ‘the one.’ This neurochemical hijacking keeps users engaged while systematically undermining their capacity for the patience and commitment that real relationships require.

Commodification extends to self-presentation. Users learn to market themselves, optimising photos and strategically timing responses. Dr Donna Freitas 417 found that young people increasingly describe themselves using marketing language—‘personal brand,’ ‘value proposition,’ ‘competitive advantage’—when discussing romantic prospects. The self becomes a product; the partner becomes a consumer. Love becomes a transaction.

Virtual vs Real Relationships

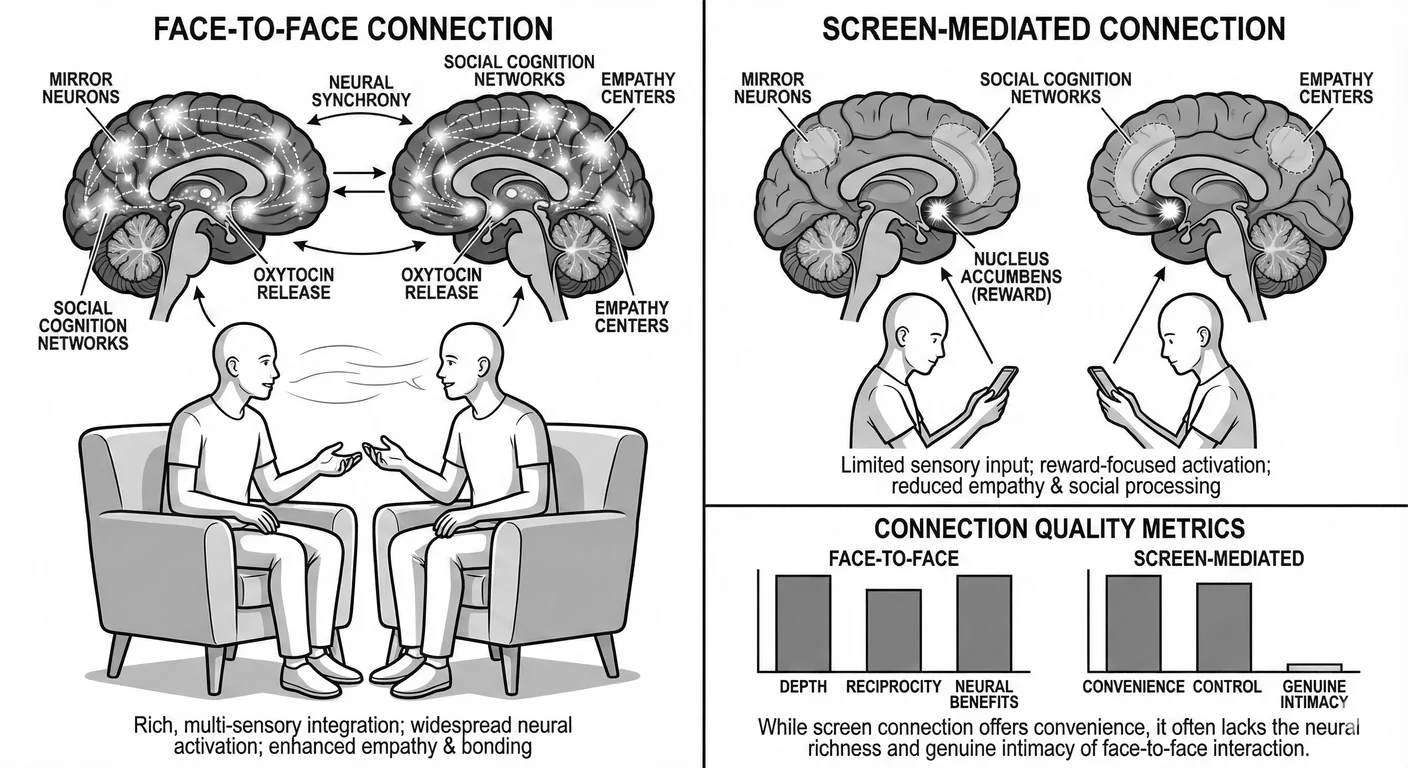

Virtual relationships, mediated through screens and platforms, operate according to different psychological and neurobiological principles than face-to-face connections, creating new forms of intimacy that often amplify narcissistic dynamics while failing to meet basic attachment needs.

Dr Susan Greenfield 489 argues that online relationships alter how empathy and social Cognitive Empathy Cognitive Empathy The ability to understand another person's perspective and mental state intellectually, without necessarily feeling their emotions. Narcissists often have intact cognitive empathy while lacking emotional empathy. develop. Face-to-face interaction involves processing microexpressions and body language cues that screens cannot transmit. The fusiform face area of the brain—specialised for facial recognition, developing through experience with faces and essential for reading emotional expressions—receives impoverished input from screen-mediated interaction. While Facebook use activates the nucleus accumbens during self-relevant feedback, it simultaneously shows reduced activation in social cognition regions during empathy tasks 854 —the reward is decoupled from genuine interpersonal understanding. Children growing up with primarily virtual relationships may fail to develop the neural circuitry necessary for reading complex emotional states, creating what Greenfield calls “autistic-like” traits in neurotypical populations.

The asynchronous nature of most digital communication allows for unprecedented control over self-presentation. Unlike face-to-face conversation, where responses must be immediate and authentic, digital communication permits crafting and curating responses. Dr Nancy Baym 90 calls this “hyperpersonal communication”—Walther’s (1996) theory that computer-mediated communication can become more intimate than face-to-face because it allows idealised self-presentation—interactions that can feel more intimate than face-to-face contact because they allow selective self-presentation. Users share only their best thoughts and most attractive angles, creating idealised versions of themselves that no real person could maintain.

Young adults with the highest social media use had twice the odds of reporting feelings of social isolation compared to those with lower use. 1008 This paradox, feeling more alone while more connected, reflects the quality of virtual relationships. Dr Matthew Lieberman 740 explains that while social media activates some of the same reward centres as in-person interaction, it fails to activate the full complement of neural systems involved in genuine social connection. Virtual relationships provide the simulacrum of connection without its full neurobiological benefits.

Parasocial relationships—one-sided emotional connections with media figures—have exploded in the digital age. Originally described with television, 571 social media has intensified the phenomenon exponentially. Users develop intense emotional connections with influencers and YouTubers, investing time and emotional energy in relationships that are inherently narcissistic—entirely Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. with no genuine reciprocity. These parasocial relationships can crowd out real relationships, offering the illusion of connection without the challenges of actual intimacy.

Jason, thirty-two, works as a software developer in Edinburgh. We talk in his flat, which is small, neat, dominated by the gaming setup in the corner: three monitors, mechanical keyboard, headset hung on a stand. The Discord notification sound pings twice during our conversation; he does not look. “I had hundreds of online friends,” he says. “People I’d been talking to for years in gaming communities, my World of Warcraft guild, my Destiny clan, three different Discord servers where I was a moderator. I knew their voices and their jokes. Some of them I’d talked to every day for five years. More than I talked to my own brother.” He is quiet for a moment, looking at the blank monitors. “When my dad died last March—a stroke, very sudden—I posted in the guild chat. Everyone was kind. Heart emojis. ‘So sorry mate.’ ‘We’re here for you.’ But when I logged off that night and sat in my dad’s empty house trying to sort through his things, I realised I couldn’t call any of them. I didn’t even have their phone numbers. I’d shared raids and jokes and thousands of hours with these people, but no one could sit with me while I cried. No one could bring me food when I couldn’t get out of bed for three days. My neighbour, a woman I’d barely spoken to in four years, she’s the one who noticed my bins weren’t out, knocked on my door, made me tea.” He looks at the gaming rig, the headset waiting. “The relationships that felt so real online turned out to be performances we were all doing for each other. Friendship-shaped things. But when I needed actual weight, they had none.”

‘Context collapse’ 150 describes how social media flattens the different social contexts we typically move through. In offline life, we present different aspects of ourselves to family and colleagues. Online, all audiences merge into one undifferentiated mass. Boyd calls this ‘lowest common denominator’ self-presentation—sharing only what is acceptable to all audiences. A flattened, performative self emerges, lacking the depth and complexity of contextual identity.

Virtual relationships often operate on what Dr Joseph Walther 1296 calls the ‘hyperpersonal model’: the tendency for online relationships to become more intimate more quickly than offline ones. Without the full range of social cues, people fill in gaps with idealised projections. The limited information available gets overweighted, creating intense but fragile connections. When virtual friends finally meet in person, the clash between Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. and reality often destroys the relationship.

The gamification of social relationships through metrics—followers and likes—transforms human connection into a competitive marketplace. Adolescents increasingly evaluate relationships through quantifiable metrics rather than qualitative experience. 936 A friend’s failure to like a post becomes betrayal; the number of birthday wishes received becomes a measure of social worth. These metrics, designed to increase platform engagement, train users in narcissistic scorekeeping rather than genuine reciprocity.

‘Phubbing’—snubbing someone in person to look at one’s phone—illustrates the prioritisation of virtual over present relationships. Phubbing significantly predicts relationship dissatisfaction and depression. 1041 Partners report feeling invisible and rejected when their significant other prioritises screen relationships over their physical presence. A vicious cycle follows: neglected partners turn to their own devices for validation, further eroding the present relationship.

Virtual infidelity has become a major source of relationship conflict. Research suggests that 70% of adults have looked through a partner’s phone, seeking evidence of virtual betrayal. 327 The Boundaries Boundaries Personal limits that define what behaviour you will and won't accept from others, essential for protecting yourself from narcissistic abuse. of monogamy become unclear in virtual spaces—is liking someone’s photos cheating? What about private messaging? Virtual relationships offer opportunities for emotional and sexual connection that bypass physical presence, creating what researchers call ‘covert intimacy’ 1353 —connections that feel more real than the primary relationship because they exist in the space of fantasy and projection.

Children’s development suffers particularly. Parent-child interaction decreased by 20% when a smartphone was present, even if not in use. 242 Children learn they must compete with devices for parental attention, internalising the message that virtual relationships take priority. They see parents constantly documenting moments rather than experiencing them, learning that life’s value lies in shareability rather than lived experience.

Digital Detox Impossibility

Digital detox has become a multi-billion dollar wellness industry—yet its very existence reveals that we have created a technological ecosystem from which escape remains nearly impossible. Employment demands constant connectivity; banking and government services require digital engagement. The extensions we accepted as conveniences have become load-bearing walls. 26

Dr Sherry Turkle 1249 describes the ‘tethered self’—identity so intertwined with digital presence that disconnection feels like death. Seventy-three per cent of students experienced significant anxiety when unable to check their phones for just 15 minutes. 1058 Those who attempt to quit often experience social death—exclusion from events organised through Facebook and professional disadvantages from LinkedIn absence.

The phenomenon of ‘digital detox privilege’ reveals class dimensions: wealthy individuals can afford human assistants to manage their digital presence, while working-class people depend on gig economy apps for survival. 362 Even successful detoxes paradoxically reinforce narcissistic patterns—Instagram posts about quitting Instagram seek the same validation the platforms provide.

Corporate surveillance capitalism makes true detox impossible even for those who try. 1372 Data collection continues through others’ devices and public cameras; the individual who deletes Facebook remains tracked through shadow profiles. Children born into this ecosystem have no reference point for non-digital existence—infants distressed when caregivers attend to phones are soothed with screens themselves, learning that technology both abandons and comforts. 1019

The Palace transforms into a Maze

Quantified self-worth, curated personas, intermittent reinforcement, and commodified intimacy—these elements constitute a single transformation: the conversion of the palace into a maze.

The healthy self builds its palace gradually through lived experience and genuine connection. This requires what Turkle calls ‘the capacity for solitude’—the ability to gather yourself before reaching outward, to know who you are before asking others to validate your existence. 1248 Digital technology offers a seductive alternative: renting space in the cloud rather than building your own palace. The extensions we accepted as conveniences have become load-bearing walls; the palace we thought we were building was never ours.

What happens when an entire generation grows up with this friction removed? Baseline data from the ABCD Study—tracking 10,000 children longitudinally—already shows that screen time in nine- and ten-year-olds correlates with cortical thinning across diverse brain regions. 962 They become, in Twenge’s words, ‘on the verge of the most severe mental health crisis for young people in decades.’ 1255 The palace walls that previous generations constructed through boredom and unmediated experience were never built for this generation. In their place: the endless scroll, the constant stimulus of someone else’s design.

The palace requires contemplation; the maze demands distraction. The palace requires vulnerability with trusted others; the maze rewards performance for anonymous crowds. The palace grows through the slow accumulation of meaning; the maze consumes meaning, converting experience into content and relationships into metrics. Every meal and every trip becomes raw material for the profile. The experience is not complete until posted. The memory is not real until shared. The self does not exist until validated.

From Neurons to Nations: The Scaling Problem

A legitimate objection arises: even if smartphones reshape individual brains, how does this translate to societal transformation? The leap from neuron to nation appears to require a bridge—some mechanism by which individual pathology becomes collective phenomenon.

But the primary bridge requires no special mechanism at all. It is arithmetic.

The Homology Argument: Same Damage, Same Outcomes

The core claim of this chapter is not that digital platforms resemble narcissistic environments but that they are narcissistic environments—producing identical neural damage through identical mechanisms. If this homology holds, scaling follows automatically.

Consider the evidence systematically:

[style=nextline,leftmargin=1.5em]

Amygdala sensitisation: Children of narcissistic parents show hyperactive amygdala response to social threat, the product of chronic unpredictability. 1219 Adolescents who habitually check social media show progressive increases in amygdala activation during social anticipation—the same structure, the same hypersensitivity, documented longitudinally over three years. 824

Prefrontal cortex thinning: Survivors of early relational trauma show reduced prefrontal grey matter, impairing emotional regulation and executive function. 1218 Heavy digital media users show accelerated cortical thinning across prefrontal regions, with dose-response relationships documented in the ABCD cohort of 10,000 children. 962

Anterior cingulate and insula deficits: The empathy circuit—anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula—shows reduced volume and connectivity in those raised in invalidating environments. 1272 Media multitaskers show reduced grey matter density in the same anterior cingulate cortex. 761 The structure that enables feeling with others atrophies in both conditions.

Attachment system hijacking: Intermittent reinforcement—the unpredictable alternation of reward and punishment—creates trauma bonds in abusive relationships by exploiting dopaminergic reward prediction error. 341 Social media platforms employ the identical mechanism: variable reward schedules explicitly designed to maximise engagement by exploiting the same neural circuitry. 26

HPA axis dysregulation: Chronic unpredictable stress in narcissistic homes recalibrates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, producing elevated baseline cortisol and impaired stress recovery. 509 Problematic smartphone use correlates with HPA axis dysregulation and elevated cortisol, particularly in adolescents. 899

This is not analogy. It is convergent damage—different inputs producing the same neural output because they exploit the same vulnerabilities through the same mechanisms.

Now apply arithmetic. If narcissistic parenting affects approximately 6 percent of children (the estimated prevalence of parents with clinically significant narcissistic traits), 1187 while smartphone exposure affects over 95 percent of adolescents in developed nations, 977 and if the neural damage is homologous, then the population-level burden of narcissistic-pattern damage has increased by an order of magnitude—not through any exotic contagion mechanism, but through sheer prevalence of exposure.

The scaling problem dissolves once the homology is established. Same damage at individual level, multiplied across billions of users, produces population-level transformation. No additional mechanism is required.

But additional mechanisms exist, and they amplify the effect.

Network Amplification: Three Degrees of Influence

Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler’s landmark research on the Framingham Heart Study—tracking 12,067 people over 32 years—demonstrated that behaviours, emotions, and health outcomes spread through social networks in predictable patterns. 243 When a Framingham resident became obese, their friends were 57 percent more likely to become obese. A friend’s friend becoming obese increased one’s own risk by 20 percent—even if the connecting friend gained no weight. The effect extended to three degrees of separation before dissipating.

The same pattern held for happiness, depression, smoking cessation, and loneliness. Your emotional state depends partly on the emotional experiences of people you have never met, two to three degrees removed in your social network. This is not metaphor; it is epidemiology.

The mechanism involves three components: homophily (we choose relationships with similar others), confounding (shared environments produce shared outcomes), and induction (behaviours actually spread from person to person through social influence). 244 Careful statistical controls in the Framingham data isolated the induction effect: behaviours genuinely propagate through networks, reshaping populations one relationship at a time.

Apply this framework to the neural adaptations documented in this chapter. If depression spreads through networks to three degrees of separation, and if habitual social media use produces depression through documented neural mechanisms, 824 then the neural reshaping does not remain confined to individual users. It propagates. The adolescent whose amygdala has been sensitised by algorithmic manipulation influences peers, who influence their peers, who influence theirs. The attention economy is not merely reshaping millions of individual brains in parallel; it is reshaping the network dynamics through which brains influence each other.

The Narcissism Epidemic Debate

A critical reader might object: if digital technology produces narcissistic adaptations, we should see rising narcissism scores in the population. Yet a 2025 meta-analysis of over 500,000 participants across 1,105 studies found no evidence for increasing narcissism on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory—if anything, scores have decreased globally over time. 929

This finding does not contradict our thesis; it clarifies it. The NPI measures grandiose narcissism—the overt, self-aggrandising presentation. What digital platforms produce is not grandiosity but contingent self-worth: identity dependent on external validation, self-esteem fluctuating with metrics, the false self performing for algorithmic approval. This is closer to vulnerable narcissism—the defensive, shame-driven variant that the NPI does not capture well.

Moreover, if everyone’s baseline shifts, no one appears more narcissistic relative to peers. The NPI is a relative measure within a population. If the entire population becomes more dependent on external validation, this registers not as rising narcissism but as a new normal. The fish cannot measure the rising water.

The stronger evidence lies not in trait scores but in behavioural and neural signatures. The 50 percent increase in adolescent depression since 2010, 1255 the documented cortical thinning in heavy users, 962 the progressive amygdala sensitisation in habitual checkers 824 —these are not self-report measures subject to shifting baselines. They are objective markers of a population undergoing neurological transformation.

Collective Narcissism and Institutional Contagion

Individual narcissistic adaptations do not remain individual. Agnieszka Golec de Zavala’s research programme on collective narcissism demonstrates how narcissistic dynamics manifest at the group level. 465 Collective narcissism—the belief that one’s group is exceptional but insufficiently recognised—predicts intergroup hostility, conspiracy beliefs, and support for authoritarian leadership. It has been measured in national, ethnic, religious, political, professional, and organisational contexts.

Crucially, collective narcissism increases in response to frustrated individual needs. 467 When personal validation is unavailable, people seek it through group identification. The platforms that frustrate individual needs for genuine connection—offering instead the simulacrum of validation through metrics—thereby increase vulnerability to collective narcissistic movements. The individual scrolling alone, their attachment needs exploited by algorithms, becomes susceptible to group identities that promise the recognition the screen cannot provide.

This provides the mechanism by which individual neural adaptations scale to institutional and political phenomena. The corporation rewarding self-promotion over collaboration, the political movement promising recognition to the aggrieved, the online community offering belonging to the isolated—all exploit the same attachment needs that the platforms have systematically frustrated. The chapters that follow are not speculation extrapolated from neuroscience; they trace documented pathways from individual vulnerability to collective manifestation.

Aggregate Cognitive Effects

Research on the attention economy explicitly addresses the scaling problem. Individual-level cognitive harms—shortened attention spans, emotional volatility, susceptibility to misinformation—do not remain isolated. When aggregated across millions of users, they produce collective outcomes: fragmented social trust, polarised communities, weakened democratic norms. 1341

What is at stake is not screen time but cognitive self-governance. The capacity for reflective reasoning that democracy requires depends on neural architecture that the attention economy systematically degrades. The prefrontal cortex that enables deliberation is the same prefrontal cortex that thins with heavy digital use. The anterior cingulate that enables perspective-taking is the same anterior cingulate that shows reduced grey matter in media multitaskers. 761 When these capacities erode across a population, the political consequences follow not as speculation but as arithmetic.

The bridge from neuron to nation requires no exotic mechanism. The homology argument provides the primary span: digital platforms produce the same neural damage as narcissistic parenting through identical mechanisms; multiply that damage across billions of users and population-level transformation follows arithmetically. The additional mechanisms—network amplification, collective narcissism, aggregate cognitive effects—enrich but do not replace this foundation. They explain why the damage propagates faster and manifests in particular institutional forms, but the basic scaling requires only the convergent damage itself: same inputs, same outputs, vastly greater exposure.

Each link in this chain has empirical support. Together they constitute the pathway by which the narcissistic dynamics of the smartphone scale to civilisational consequence.

Conclusion: The Acceleration Continues

Molly Russell’s case embodies an extreme outcome, but the underlying dynamic affects millions. In the months before her death, she had viewed over 16,000 pieces of content, 2,100 of them related to suicide and self-harm. The algorithm had learned what engaged her. It served her more. She died at fourteen, and a coroner ruled for the first time in legal history that social media had contributed to a child’s death.

Digital platforms exploit the same psychological vulnerabilities that narcissistic families exploit. The intermittent reinforcement that keeps children of narcissists perpetually hoping for parental approval 1146 operates identically in the variable rewards of likes and notifications. The false self that develops in response to conditional love 1333 finds perfect expression in curated profiles. The hunger for mirroring that Kohut 674 identified as central to narcissistic development is now commodified at industrial scale.

Turkle’s 1249 research documents the consequences: diminished capacity for solitude and relationships that are wider but shallower. Twenge’s 1255 longitudinal data demonstrates the epidemiological impact: rates of depression and anxiety among young people rising in lockstep with smartphone adoption. Zuboff’s 1372 analysis indicates the economic logic: human attention and behaviour extracted as raw material, processed into prediction products, sold to advertisers. The system is working as designed; the design simply does not prioritise human wellbeing. The developmental pathways to narcissism explored in Chapter 4 (early trauma, inconsistent parenting, lack of secure attachment) now have a digital accelerant, with platforms engineering the very conditions that create narcissistic adaptations in otherwise healthy individuals. Adolescents with depression—now epidemic in high-screen-time populations—show reduced connectivity in the uncinate fasciculus, 1258 the white matter tract connecting prefrontal cortex to amygdala that enables emotional regulation. Digital environments damage the same neural pathway that early relational trauma disrupts. A three-year longitudinal fMRI study has now demonstrated causation, not merely correlation: adolescents who habitually check social media show progressive increases in bilateral amygdala and anterior insula activation—the very structures that process social reward and threat—while non-habitual users show decreases in the same regions. 824 The attention economy is literally reshaping the developing brain.

Transformation is already intergenerational. Parents who cannot disengage from their devices model digital dependency for children who know no alternative. Attachment disruptions documented by Radesky 1019 —infants showing distress when caregivers attend to phones, then being soothed with screens themselves—suggest that neurobiological patterns discussed in Chapter 6 may form differently in children raised with ubiquitous digital mediation.

The evidence base, while not yet complete, is converging. What remains to be established is not whether digital environments affect brain development—the longitudinal studies have demonstrated causation—but whether the mechanism is identical to narcissistic parenting at the cellular level, whether the effects are reversible, and whether adult brains beyond the adolescent sensitive period are equally vulnerable. These questions await the cross-population neuroimaging studies now being designed. What we can say with confidence is that the behavioural signatures are identical, the psychological damage is equivalent, and the neural structures affected—amygdala, anterior insula, prefrontal cortex—are the same. The burden of proof has shifted: it is no longer incumbent on critics of digital culture to prove harm, but on the platforms to prove safety.

One counter-argument is the ‘Goldilocks hypothesis’: large-scale datasets sometimes show a J-shaped curve where moderate digital use correlates with better wellbeing than zero use, and effect sizes for screen time on depression are small—comparable, critics note, to eating potatoes. 1011 But this finding is precisely what our theory predicts. A ‘good enough’ digital environment, like a good enough parent, causes no harm. The damage comes not from technology itself but from the relational dynamic—the dependency and the habitual checking that creates addiction-like patterns. This book is not against technology; it is against the algorithmic exploitation of attachment needs.

Another counter-argument reframes brain changes as ‘adaptation’ rather than damage: just as London taxi drivers grow their hippocampi for navigation, perhaps digital natives are simply specialising for rapid information processing. But adaptation for what? The grey matter reduction documented in the anterior cingulate cortex—the seat of empathy and emotional regulation—represents loss, not efficiency. 761 We are not adapting to be smarter; we are atrophying the neural basis that makes us capable of genuine connection. Scales forming, not skills.

We do not yet have a study that places a survivor of narcissistic parenting and a heavy social media user in the same scanner to compare their scars. But the map of the damage is identical. In the narcissistic home, the amygdala swells from the labour of constant threat detection; in the digital world, the amygdala shows the same hypersensitivity from the labour of ‘social anticipation.’ 824 In the narcissistic home, the prefrontal cortex thins as the child abandons self-regulation to focus on regulating the parent; in the digital world, the prefrontal cortex thins as the user outsources regulation to the algorithm. 1247 In the narcissistic home, the anterior insula—the seat of empathy—underperforms because the child’s feelings are dangerous; in the digital world, the same region atrophies because the screen decouples reward from genuine connection. 761 The inputs differ—one is a parent, one is a phone—but the structural transcription is the same. The brain is building the architecture of diamorphic agency: a self designed to perform and survive, rather than to exist.

Possibilities for intervention exist. Przybylski’s 1010 work on FOMO suggests that the fear of missing out correlates with unmet psychological needs—autonomy and relatedness—rather than being an inevitable response to technology. Addressing those underlying needs may reduce vulnerability to platform manipulation. Turkle 1248 advocates for what she calls ‘sacred spaces’—times and places protected from digital intrusion—as regular restoration short of complete detox. The capacity for solitude, she argues, is the foundation for genuine connection; without it, we use others merely as mirrors.

The narcissistic dynamics amplified by technology do not remain confined to personal devices. They have infiltrated workplaces, shaping corporate cultures that reward self-promotion and metric performance. They have entered politics, elevating spectacle over substance. The chapters that follow trace these patterns through institutional spheres—the corporation and the political arena—examining how the same psychological vulnerabilities exploited by platforms manifest at organisational and societal scales.

\FloatBarrier