The way we talk to our children shapes their inner voice.

— —Peggy O’Mara

Introduction: The Child as Mirror

In the myth that gives this book its title, Narcissus perishes gazing at his own reflection in a still pool. But we rarely consider what happens to those forced to serve as that pool, the living mirrors in which narcissists seek their reflection. For children of narcissistic parents, this is daily existence, their mythology made flesh. They become the surface upon which a parent obsessively gazes, the parent transfixed by their own reflection, blind to the child.

Sarah, thirty-four, sits in her therapist’s office, struggling to articulate something she has never had words for. “My mother was obsessed with me,” she says. “That’s what everyone thought. She knew every detail of my life, controlled every choice, introduced me to strangers by reciting my achievements like a CV. But sitting here now, trying to tell you who I actually am…” She falls silent, then: “I don’t think she ever saw me. Not once. She saw herself, what I reflected back to her, what I proved about her. The actual me, underneath? I’m not sure that person was ever allowed to exist.”

The central paradox: the narcissistic parent fixates on their child with an intensity that looks like devotion but functions as erasure. Like Narcissus mesmerised by the pool, they stare and stare, but they are not seeing. The child transforms into a mirror, reflecting back the parent’s grandiosity, absorbing their shame, proving their worth to the world. The living, breathing human beneath that reflective surface—curious and needing—remains invisible. Unseen.

The damage compounds because this mirror-child exists within a maze of external expectations that reinforce the erasure. Family members comment on how much she resembles her mother. Teachers judge him by his father’s reputation. Neighbours see the family name before they see the child. The community reflects back the parents’ stories: their status, their struggles, their glory. “You’re just like your father”—whether meant as compliment or curse, it functions identically—erasing the individual self beneath a projected identity. The child learns they are nothing more than a continuation, a reflection of reflections stretching back through generations—never a person in their own right.

Consider how social structures encode this erasure. Surnames pass down like property deeds. Sons become ‘Junior’ or ‘III,’ their names not their own but inherited titles. Royal houses assign regnal numbers, Charles III, Elizabeth II, as if individual identity were merely a placeholder in a dynastic sequence. Family crests, ancestral seats, inherited wealth, storied reputations: these are the maze walls within which children must find themselves, walls built from centuries of validation disguised as tradition. ‘Honour thy father and mother’ transforms into a command to reflect and subordinate individual selfhood to the family story—love is never part of the equation.

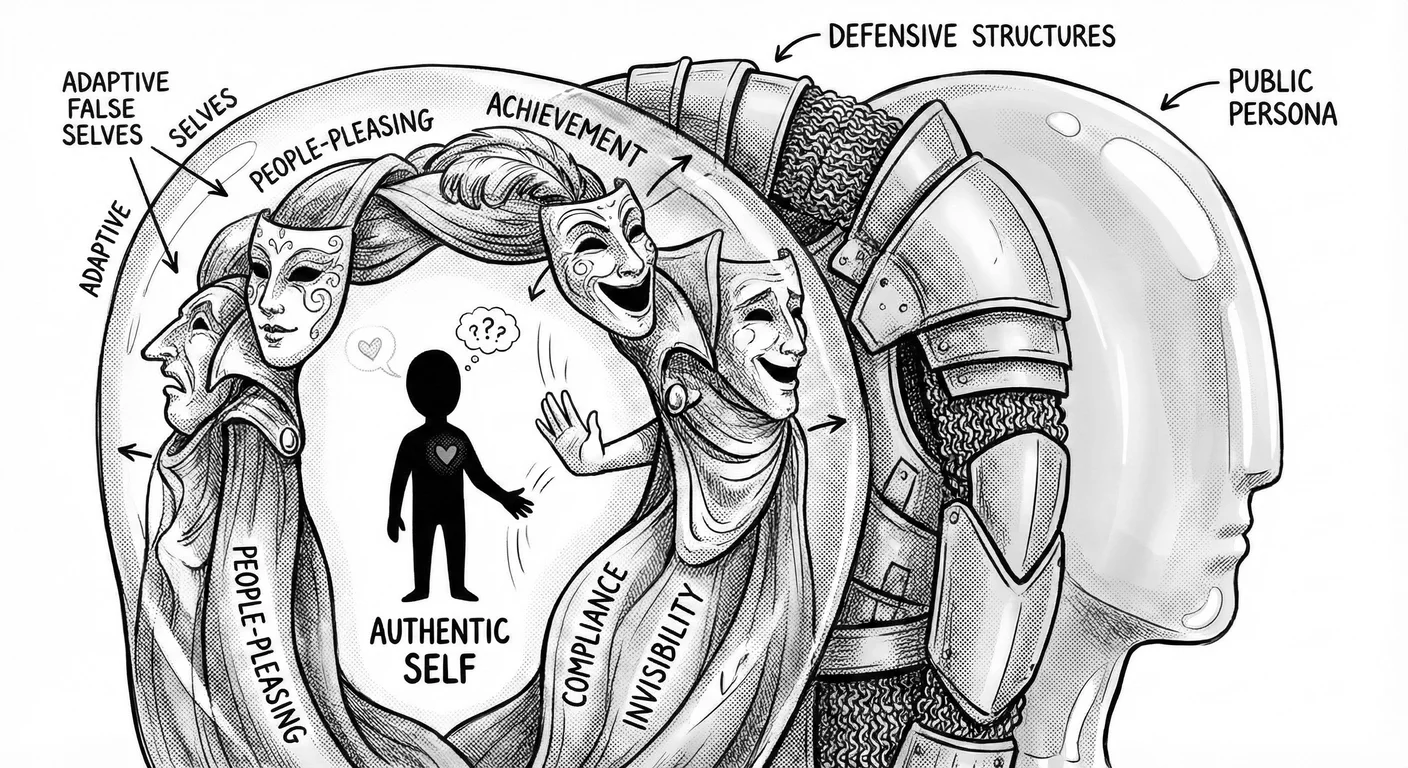

Overwhelmed by this maze of mirrors and expectations, children adopt survival strategies. They learn the manipulation and performance that their parents modelled. They become what is expected, the reflection rather than the person, because authentic selfhood brings only punishment or invisibility. Each adaptation, each surrender of authentic self, adds new walls to the internalised maze. What began as external expectation becomes internal architecture. The child builds their own prison, one compromise at a time, until they no longer remember there was ever anything to imprison.

Contrast this with what healthy development looks like. When parents are capable of genuine seeing, they welcome a new palace of the mind into their home, a fresh set of eyes and feelings, opening new doors and windows onto their shared world, a being with their own architecture, their own rooms to explore, their own blueprints to draw. John Bowlby’s 146 attachment research established that children need a secure base from which to explore the world. These parents do not gaze at their children seeking reflection; they look with curiosity at someone genuinely other, someone becoming. They build together. They play. They take risks and laugh at failures. When the child struggles, parents provide scaffolding, not scripts. When the child succeeds, joy is shared, not claimed.

In healthy families, the child is rooted rather than reflected. Secure attachment forms the foundation from which they can venture into the world, as themselves, never as mere extensions of their parents. They are welcomed into various contexts: school, friendships, community, because their parents have built genuine connections rather than performed status. These children grow into adults who know their own minds, who can distinguish their desires from others’ expectations, who have faces, never mere surfaces.

Alice Miller’s 863 ‘drama of the gifted child’—exceptional sensitivity deployed in service of parental needs rather than authentic selfhood—plays out in countless variations. Narcissistic parents transform children into reflective surfaces, external structures reinforce this erasure, and the survival strategies children adopt can perpetuate the very patterns they suffered. The false self (see Chapter 1) begins forming as early as infancy, when authentic expression brings punishment or invisibility.

Yet paths out of the maze exist. The neuroscience of attachment 1099 reveals how early relationships literally shape the brain, creating patterns that persist into adulthood, and how those patterns can, with great effort, be rewired. Therapeutic approaches from EMDR to Internal Family Systems offer tools for dismantling internalised walls and recovering the authentic self buried beneath decades of reflection. And the growing community of adult children of narcissists, finding each other online and in support groups, demonstrates that isolation can be broken, that being truly seen, perhaps for the first time, is possible.

The Perfect Parent Paradox

The Hall of Mirrors

The narcissistic family home functions as a hall of mirrors—surfaces everywhere reflecting the parent’s image back to them, each family member positioned to enhance that reflection. Social media has amplified this architecture dramatically. Facebook, Instagram, and mommy blogs have become digital halls of mirrors where the narcissistic parent can curate their reflection for thousands of admirers, with their children serving as the most polished surfaces of all.

The narcissistic parent gazes at such images as Narcissus gazed at the pool: entranced by what they see, oblivious to anything beneath the surface. Their primary concern is the reflection, how the child makes them appear, never the child themselves. They craft elaborate narratives of parenting excellence, often believing their own mythology even while engaging in abuse behind closed doors. The child learns early that their role is to maintain the reflective surface: smile on cue, perform happiness, never let the mirror crack.

This hall of mirrors extends beyond digital spaces. These families appear perfect at church, at school functions, at neighbourhood gatherings. The narcissistic parent often holds positions of community respect, PTA president, youth sports coach, church volunteer, roles that provide validation while making it harder for children to be believed. Malkin 788 observes that narcissistic parents seek such positions precisely because they add more mirrors to the hall, more surfaces reflecting their excellence.

The community itself transforms into another mirror. When teachers and neighbours all reflect back the parent’s preferred image, the child faces a devastating choice: trust their own experience or trust what everyone else seems to see. “Maybe I’m the problem. Maybe I’m ungrateful. Everyone else thinks she’s amazing.” Gaslighting by architecture—systematic manipulation causing victims to question their own sanity and perception of reality: the hall of mirrors so complete, so consistent, that the child’s own perception seems like the distortion.

The rise of ‘sharenting’—parents sharing extensive details of children’s lives online—has made these mirror-halls vast and permanent. A 2010 survey found that 92 per cent of American two-year-olds had an online presence, a figure Steinberg 1178 notes has likely increased since. For narcissistic parents, this digital architecture offers extensive reflecting surfaces. Every milestone, every emotion, every private moment becomes content to be polished and displayed. The child grows up rarely knowing experience that is not simultaneously performance, rarely seeing themselves except as reflection. Here the validation economy (detailed in Chapter 1) scales to social media metrics—likes and shares become the currency of parental worth, with the child as the content generating that supply.

The Trophy Child: Polished for Display

If the child is a mirror, the trophy child is a mirror polished to blinding perfection, angled precisely to catch the light and reflect the parent’s glory to maximum effect. These children become what Brown 164 calls ‘narcissistic extensions’—appendages of the parent’s self, never separate people, housed in smaller bodies. Like a prized painting or a luxury car, they exist to be displayed, admired, envied. The child beneath the polish is irrelevant.

The polish required depends on what the parent values. For some, academic brilliance is the only acceptable sheen. For others, athletic prowess or physical beauty. Some parents create trophies from suffering itself, garnering sympathy as the devoted caretaker of a sick or troubled child: a phenomenon that, at its extreme, becomes what Feldman 377 calls Munchausen by proxy, where parents fabricate or induce illness in their children to enhance their own reflected glory as martyrs.

The pressure is relentless. Trophy children must achieve in the right way: the way that maximises parental credit. A child who excels in art when the parent values athletics, or pursues a lucrative but unglamorous career over a prestigious one, finds themselves suddenly tarnished, devalued, shoved to the back of the display case. The message is clear: your value is your reflective quality. Lose the polish, lose everything.

In affluent communities, this dynamic scales into what sociologist Annette Lareau 711 calls ‘concerted cultivation’—intensive parenting aimed at maximising children’s displayable accomplishments. Private tutors and elite sports programmes: an entire industry exists to help parents polish their mirrors brighter than the neighbours’. The child influencer phenomenon exemplifies the logical endpoint: children literally monetised, their childhood experiences converted to content, their developing selves reduced to engagement metrics and sponsorship deals.

The Stauffer family scandal of 2020—YouTube family vloggers who ‘rehomed’ their adopted autistic son after years of monetising his story—revealed what happens when the child can no longer provide adequate reflection. The mirror that does not shine brightly enough gets discarded. The narcissistic parent’s inability to see the child as separate from themselves merges with capitalism’s reduction of everything to market value.

For trophy children, the damage persists long after leaving home. Many develop achievement addiction, a compulsive need to achieve that the internalised parental voice demands ever more insistently. They reach their thirties and forties still polishing and performing, still seeking the approval that was never actually about them. Others experience collapse when they achieve something the parent cannot claim, or when age makes certain achievements impossible. The identity built entirely on being a display object crumbles, revealing the emptiness where a self should have been.

The Mythology of Sacrifice

Every hall of mirrors needs a mythology, and narcissistic families construct elaborate ones. The central narrative: the parent as long-suffering martyr, sacrificing everything for ungrateful children who can never adequately repay the debt. This mythology serves multiple functions—it garners admiration from observers, guilt-trips children into compliance, and above all, it obscures the real transaction: the parent is extracting, never giving; investing in their own reflection, never truly sacrificing.

‘Everything I do is for you’ echoes as the family motto. The parent who screams for hours claims it is because they care so deeply. The mother who invades every boundary insists she loves too much. The father who criticises relentlessly frames it as helping. McBride 830 describes how narcissistic mothers excel at this reframing, turning emotional abuse into evidence of superior love.

Real sacrifices of time, money, and energy are tallied and presented as unpayable debts. ‘I gave up my career for you,’ the mother reminds, not mentioning she uses this sacrifice to live vicariously through her daughter. ‘I work seventy hours a week to give you everything,’ says the father whose workaholism predated his children. Financial provision substitutes for emotional presence. Private schools, expensive clothes, lavish vacations—evidence of excellent parenting while the parent remains emotionally absent or cruel. When children express emotional needs, they are reminded of material advantages, as if trust funds could substitute for trustworthy attachment.

Lisa, forty-one, describes the bind: “My mother told everyone about her sacrifices, driving me to dance classes five days a week, spending thousands on costumes. True, she did those things. But she also told me I was fat in my leotard, that I’d never be as good as the other girls, that I was wasting her money with my mediocre talent. The sacrifices were for her dream of having a dancer daughter, not for me. I hated dancing. But quitting would mean I was ungrateful, would crack the mirror, would ruin everything she’d ‘sacrificed.’,”

The martyr performance makes it impossible for children to have needs. How can you tell your mother you are depressed when she is perpetually on the verge of collapse? How can you ask your father for emotional support when he is killing himself to provide? The child learns their inner life is a burden, their authentic self an imposition on the family mythology.

This mythology draws power from grains of truth. Parenting does involve sacrifice. But the narcissistic distortion lies in the purpose: healthy parents sacrifice for the child’s genuine wellbeing; narcissistic parents invest in their own reflection, expecting returns in obedience and glory.

The Prison of Legacy

Here is the cruelty that distinguishes narcissistic parenting from mere dysfunction: the parent who cannot escape their own prison ensures the child cannot escape either through active undermining, not mere neglect or incompetence. The child must remain a mirror. The moment they threaten to become a separate person, they become worthless.

Consider the father who is loving, protective, generous, as long as the child reflects his ambitions. He pays for tutors, coaches, equipment. He attends every match, every recital. He sacrifices weekends, holidays, money. From outside, he appears devoted. He would tell you, with complete sincerity, that he would die for his children. And for the child-as-mirror, this is true.

Watch what happens when the child chooses differently. The son who decides not to become a doctor. The daughter who wants a university across the water, not the one where Father’s connections matter. The child who falls in love with the wrong person or pursues the wrong career.

The generosity vanishes. Not gradually: overnight. The university fees? “You’re on your own now.” The emotional support? Withdrawn. The phone calls? Silence. Or worse: the drip-feed of just enough to maintain control. Enough money to survive but not to thrive. Enough contact to prevent full independence. Enough hope to keep the child circling back, believing that if they just find the right words, the right gesture, the right achievement, the father they knew will return.

He will not. That father never existed. What existed was a man who loved his reflection, and the moment the reflection showed someone else’s face, the love evaporated, because it was never love for the child at all. It was love for himself, reflected in the child’s compliance. The parent who would have died for the child-as-mirror feels nothing for the child-as-person. Nothing. The child becomes disposable.

This is erasure, not mere ambivalence or disappointment. The narcissistic parent finds the child’s freedom intolerable because that freedom exposes a truth they cannot bear: that escape from the prison was always possible. That their own imprisonment (in their wounds, their defences, their desperate need for supply) was a choice, or at least a failure to choose differently. The child who builds their own life, who develops tastes and values and relationships independent of parental need, is living proof that the parent could have done the same. And so the child must be punished for succeeding rather than failing, for being free rather than for being bad.

Religion and culture provide ready-made tools for this crippling. ‘Honour thy father and mother’ transforms into a shackle. Filial piety is weaponised. The child who seeks therapy becomes sinful; the one who sets boundaries becomes treasonous to family and culture. Surnames pass like property deeds, marking children as continuations rather than beginnings. Sons become ‘Junior’ or ‘the Third’, their names inherited placeholders announcing: you are a position in a sequence. Royal houses make this explicit with regnal numbers. Charles III, Elizabeth II: identity as placeholder, selfhood as succession.

Every family that prioritises reputation over reality, legacy over life, builds the same prison. ‘What will people think?’ governs all decisions. “We don’t do that in this family” closes doors before children know rooms exist. The family name must be protected. Honour must be maintained. The ancestors are watching. And beneath these noble-sounding imperatives lies the real demand: remain my mirror. Do not become yourself. I cannot survive your freedom.

The child internalises these bars. What began as external control becomes internal architecture. They learn to judge themselves by the family story, to feel shame when they diverge from the prescribed path. The prison that once surrounded them now exists within them. They carry the keys but cannot find the locks, because they no longer remember an outside exists.

The Blank Mirror

The Face That Does not See

What happens when a mirror looks at a mirror? Nothing is reflected. No image forms. The child seeking emotional connection with a narcissistic parent experiences exactly this: reaching towards a surface that cannot reflect them back because it is itself seeking reflection.

In 1978, developmental psychologist Edward Tronick and colleagues published the Still Face Paradigm 1237 , demonstrating this devastation experimentally. Mothers maintained neutral, unresponsive expressions while facing their infants. Within moments, babies became distressed, trying to reengage: smiling, reaching, eventually crying. When mothers remained unresponsive, infants withdrew, showing what Tronick described as ‘hopeless’ facial expressions. The experiment lasted only minutes and was followed by reunion and repair.

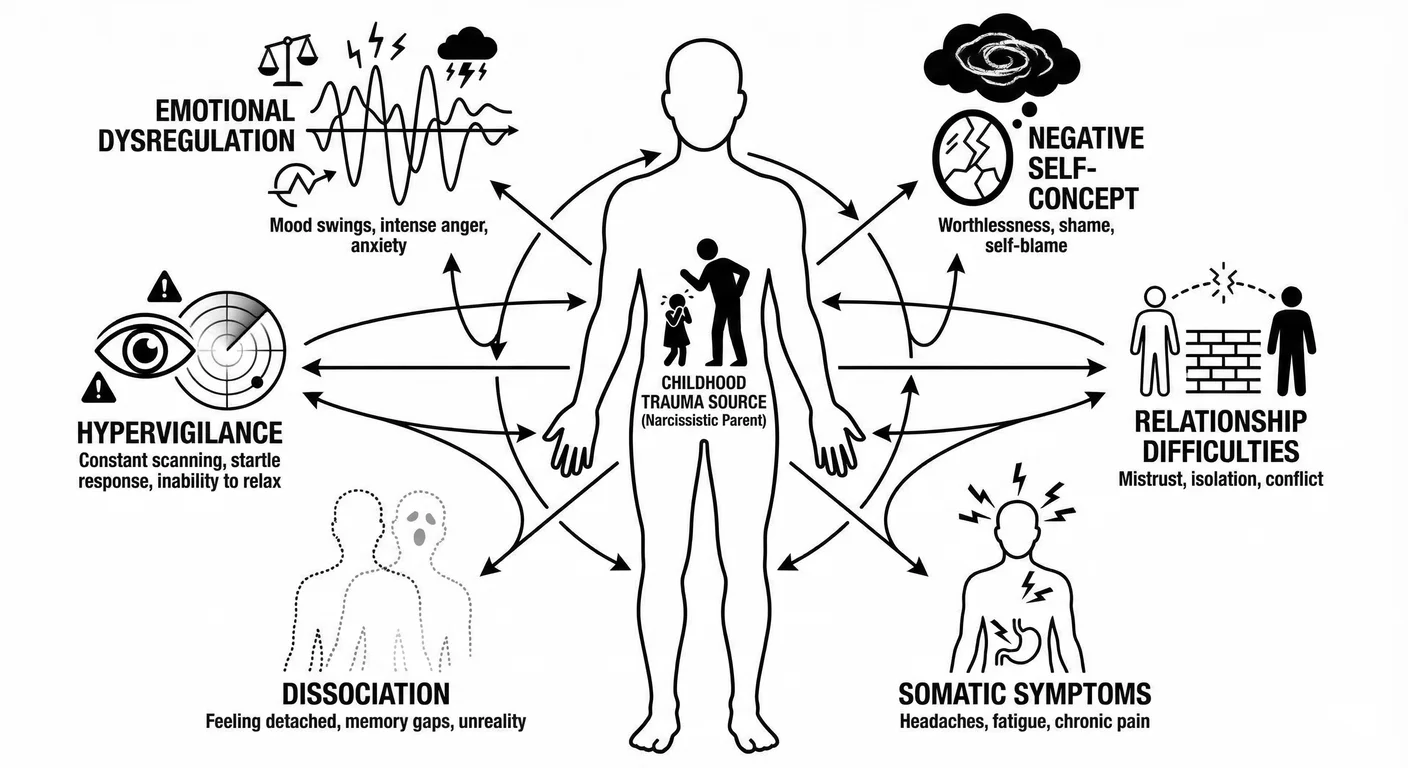

For children of narcissists, no repair comes. The still face is permanent. The parent may be physically present but gazes past the child, through them, seeking their own reflection rather than perceiving the small person before them. Schore 1099 has shown that such chronic non-seeing literally shapes the developing brain. Neural circuits for emotional regulation and self-soothing require thousands of attuned interactions to form properly. The narcissistic parent’s emotional absence does not just hurt feelings—it alters the architecture of the child’s mind.

Unable to be seen, the child learns to see everything else with desperate intensity. Sarah describes this hypervigilance: “I could tell from my mother’s footsteps on the stairs what mood she was in. The angle of her shoulders entering a room, the quality of her silence—I’d catalogued hundreds of signals that told me if I was safe or in danger. I thought everyone lived like this, constantly scanning.” Pete Walker 1292 calls this the ‘fawn’ response—acute sensitivity to others’ emotional states coupled with compulsive need to please and appease.

This vigilance costs everything. The child’s nervous system remains chronically activated, preparing for emotional danger. Cortisol floods the developing brain. What Van der Kolk 1272 calls ‘the body that keeps the score’ accumulates: anxiety disorders, panic attacks, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome—conditions rooted in a nervous system that learned the world was perpetually unsafe because the one person who should have seen the child never did.

The intermittent nature of the narcissistic parent’s emotional availability creates what behavioural psychologists call an intermittent reinforcement schedule—unpredictable rewards creating persistent behavioural responses—the most powerful mechanism for creating psychological dependence. Like gamblers at a slot machine, children learn that if they just try hard enough, if they can just be good enough, they might hit the jackpot of parental attention and affection. This unpredictability creates trauma bonding, an intense attachment that paradoxically strengthens in response to abuse.

Siegel’s 1141 work on interpersonal neurobiology reveals how the narcissistic parent’s emotional unavailability disrupts the child’s development of mindsight, the ability to see the mind of self and others. Children need thousands of repetitions of having their emotional states accurately perceived and reflected back to them to develop this capacity. The narcissistic parent, preoccupied with their own internal world, fails to provide this mirroring. The child grows up unable to clearly perceive their own mental states or accurately read others.

The Distorted Reflection

Donald Winnicott 1333 understood that the parent’s face is the child’s first mirror. In healthy development, the mother looks at her infant and reflects back what she sees: you exist, you are real, your feelings matter, you are you. The child gazes at their mother’s face and sees themselves beginning to take shape.

The narcissistic parent’s face reflects only themselves. When the child approaches with excitement, the parent either dismisses it (if it does not enhance their reflection) or co-opts it (‘You get your intelligence from me’). When the child expresses fear or sadness, the parent becomes angry at having to acknowledge someone else’s experience, competitive (‘You think you have problems?’), or hijacks the moment for their own emotional discharge. The child looks into the parent’s face and sees: nothing. Or worse, sees only the parent’s distorted projections looking back. This systematic failure of mirroring forges the false self described in Chapter 1, a defensive adaptation necessary for psychological survival.

Heinz Kohut 674 identified three developmental needs essential for healthy self-formation: mirroring (having one’s experience accurately reflected), idealisation (having a stable figure to internalise), and twinship (experiencing kinship with another). The narcissistic parent fails all three. They cannot mirror because they see only themselves. They cannot be idealised because they are unstable. They cannot provide twinship because they are unable to accept the child as genuinely separate.

Alice Miller 863 called this the ‘false self’—a reflective surface the child constructs to survive. They learn to hide authentic feelings, needs, experiences, developing instead a persona designed to secure whatever crumbs of safety the parent might provide. This false self becomes so practised, so automatic, that the child loses touch with whoever they actually are. By adulthood, they may have no idea.

Jessica, twenty-nine: “My therapist asked what I enjoyed doing. I literally couldn’t answer. I knew what I was good at, what others praised, what made people like me. But my own enjoyment? It was like being asked to describe a colour I’d never seen. I’d spent my entire life shape-shifting into whatever got approval, first from my mother, then from everyone.”

The false self protects in childhood but imprisons in adulthood. Relationships remain superficial—how can you reveal a self you do not know? Careers are chosen for appearance rather than fit. Life becomes performance without an authentic performer. The narcissistic parent’s distortions extend to reality itself: ‘That never happened,’ “You’re too sensitive,” “You’re remembering it wrong.” The child learns to distrust their own perceptions, creating what Stern 1184 calls ‘the gaslight effect’—chronic self-doubt, confusion about one’s own experience, a fog that never lifts.

Chronic emptiness follows—not depression exactly, though the two often coexist. Emptiness runs deeper: no solid self at the core, no steady sense of ‘I’ persisting across contexts. Where a person should be, only a reflective surface waits to show others what they want to see.

The One-Way Mirror

The narcissistic parent’s empathy deficit functions like a one-way mirror: they can see out, read others’ emotions when useful, but nothing passes through from the child’s side. Neuroimaging studies by Diamond 308 confirm this asymmetry: narcissists show normal brain activation when thinking about others’ mental states (cognitive empathy) but reduced activation when exposed to others’ emotional pain (affective empathy). They can calculate what you feel; they cannot feel it with you.

For the child, deep invisibility sets in. Joys go uncelebrated, sorrows uncomforted, fears dismissed. Childhood injuries are met with irritation rather than comfort—a broken arm at eight, and a parent angry about having to leave a work party, dismissing tears as drama. The lesson learned: my pain is an inconvenience, my tears an embarrassment.

Children adapt to this one-way mirror in opposite directions. Some develop hyperempathy—hypervigilant tracking of others’ emotional states, a form of survival radar distinct from true empathy, calibrated to prevent parental storms. Orloff 938 describes these ‘empaths’ who absorb others’ emotions, lose track of their own, feel responsible for managing everyone’s feelings. They become therapists, nurses, teachers, professions valuing sensitivity, but burn out quickly, having never learned where they end and others begin. They are drawn to narcissistic partners who exploit their porousness.

Others protect themselves by shutting down entirely through learned dissociation, a defensive numbing to all emotions including their own. These individuals appear cold, uncaring, but this is from necessity, not narcissism: if feeling meant absorbing a parent’s chaos, numbness was the only safe harbour.

The Fractured Mirror

Splitting: The Parent’s Reflection in Pieces

The narcissistic parent cannot tolerate a single, complex reflection. They need mirrors that show only what they wish to see: their brilliance and their victimhood. So they shatter the family into fragments, assigning each child a piece of the parental self to reflect back. This is splitting: the primitive defence Melanie Klein 669 first described, where the world divides into all-good and all-bad—golden child and scapegoat. This defence mechanism, characteristic of Cluster B personality disorders (see Chapter 2), prevents the integration necessary for psychological health.

The golden child reflects the parent’s idealised self—all the qualities they claim. The scapegoat reflects what they disown: shame and inadequacy, everything intolerable. Other children become supporting shards: the lost child who conveniently vanishes from the reflection, the mascot who deflects with humour, the caretaker who holds the frame together. Donaldson-Pressman 321 details how each role serves specific psychological functions for the parent. The children’s actual selves are irrelevant; they exist to reflect assigned fragments.

Role assignment follows the parent’s projective logic, not objective reality. One child becomes golden because they have the parent’s eyes. Another is scapegoated because they resemble a hated ex. Birth order, gender, temperament, random associations, any of these can determine a child’s fate. Once assigned, roles become self-reinforcing. The family system needs its golden child and its scapegoat the way a stage play needs its hero and villain. The script was written before any child was born.

Triangulation prevents siblings from seeing each other clearly. Payson 964 describes the narcissistic parent whispering to each child about the others’ failings, sharing ‘secrets’ that create artificial intimacy while sowing distrust. Children who might be natural allies become competitors, each fighting for the reflective position that seems safest. “Why can’t you be more like your cousin?” extends the triangulation beyond the home: the maze of comparison never ends.

The damage outlasts childhood. Golden children may genuinely believe their superiority, having internalised decades of parental messaging. Scapegoats harbour resentment towards siblings they see as complicit. These dynamics persist into adulthood, even after the narcissistic parent’s death. The shattered mirror cannot easily reassemble; each child took their assigned fragment into the world.

The Golden Child: Gilded Cage

From outside, the golden child appears lucky: praised, resourced, adored. Closer inspection reveals a cage. The gold is leaf-thin, and beneath it, the child suffocates.

The golden child is loved for what they reflect, never for who they are: the parent’s idealised self. Every achievement belongs to the parent who ‘created’ them. Every failure constitutes betrayal, narcissistic injury, cause for immediate devaluation. Golomb 469 calls this ‘psychic murder’—systematic annihilation of authentic self in favour of a performance that serves parental needs.

The enmeshment often reaches what clinicians recognise as emotional incest—inappropriate emotional intimacy where a child fills the role of spouse or romantic partner without sexual contact—the child evolving into the parent’s therapist, confidant, reason for living. This suffocating intimacy prevents autonomous identity. The golden child must maintain achievement and the family mythology itself: no therapy (that would suggest problems), no boundaries (that would be ungrateful), no interests that diverge from parental vision. They are trapped in a role they never auditioned for, in a play they cannot leave.

When golden children attempt individuation, their own relationships, careers, paths, they face narcissistic rage. The parent who idealised them devalues them completely. The fall from grace reveals what they always feared: the love was conditional, contingent on reflection. Many describe this devaluation as more traumatic than the original enmeshment because it exposes the transaction that was always there.

Forward 406 notes that golden children often experience their crisis later than scapegoats. Positive treatment delays recognition of dysfunction. They may not question the system until middle age, when perfection becomes unsustainable or when they see their own children being assigned roles. Decades of pattern make recovery particularly challenging.

The Scapegoat: The Dark Reflection

If the golden child reflects the narcissist’s grandiose self, the scapegoat holds the dark reflection: the shame, self-hatred, and disowned failures that cannot be tolerated. Every mirror has a shadow side, and the scapegoat evolves into the repository for everything the narcissist cannot bear to see in themselves. They are blamed for all family dysfunction, labelled the problem child, the difficult one, the source of every strife. Yet this painful role, paradoxically, may offer advantages for eventual escape.

Scapegoat selection often seems irrational. Sometimes it is the sensitive child whose emotions the narcissist cannot tolerate—feelings they have suppressed in themselves, now visible in their offspring. Sometimes it is a resemblance to a hated ex-spouse. Sometimes it is the child who questions the family mythology or shows early independence: the one whose reflection does not hold still. Often, it is simply the child born when the parent needed someone to blame.

Bancroft 71 describes the scapegoat as a lightning rod for family dysfunction: “When there’s a scapegoat to blame, no one has to look at the real sources of family problems. The narcissistic parent’s abuse, addiction, infidelity, or failure can all be attributed to the stress of dealing with the ‘problem child.’ Other family members collude in this scapegoating because it offers them relative safety from the narcissist’s rage.”

We see this pattern in patients who still flinch when voices rise, even in excitement—bodies remembering childhoods where they were the designated problem. If a sibling got in trouble, they were the bad influence. If parents fought, they caused the stress. The logic was circular and inescapable: quiet meant sulking, speaking meant drama, and any achievement meant showing off. There was no safe position, no correct answer. Many describe hiding as children, trying to take up less space, as though the problem were their physical existence. Years of therapy later, they understand intellectually that they were convenient containers for dysfunction that predated them, but the body still believes it. The shoulders are still up.

Scapegoats often develop complex post-traumatic stress disorder from years of blame and punishment for things beyond their control, along with severe anxiety and depression. Many turn to substances or self-harm to manage overwhelming shame. The constant message that they are bad, wrong, unwanted becomes internalised as core shame: the belief that they are deeply defective, that the dark reflection is their true face.

The scapegoat role carries paradoxical advantages. Already devalued, they have less to lose by recognising family dysfunction. They are more likely to seek therapy, question the family mythology, pursue their own path. The very characteristics that made them scapegoats—sensitivity and truth-telling—become strengths in recovery. They have been practising for escape all along.

Campbell 195 notes that scapegoats often become family truth-tellers, naming the dysfunction everyone else denies—dangerous in childhood, valuable in adulthood. Many become therapists, writers, activists, channelling injustice into helping others. They develop sharp instincts, having learned early to see through false narratives.

The scapegoat’s path to healing involves grieving the family they had and the one they never had. Unlike golden children who may have memories of being valued, scapegoats must reckon with a childhood devoid of parental love. This grief is immense. Many scapegoats internalise their role so deeply they continue scapegoating themselves long after leaving the family, still carrying the dark mirror fragment, still seeing themselves through its distorted surface—complicating the grief further.

The Invisible Ones

While the golden child and scapegoat receive the most attention, other children occupy equally damaging if less visible roles. The lost child, the mascot, the caretaker, these forgotten ones may escape direct fire but suffer severe neglect. They learn to become invisible, to avoid reflecting at all. In a house of fractured mirrors, they are the spaces between the shards, present but unnoticed, needed but unseen.

The lost child, identified by Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse 1310 , is the one who disappears. They learn early that invisibility is safest. Do not cause problems, do not have needs, do not draw attention. Hours alone in their room, lost in books or video games, or rich fantasy lives that provide escape from family chaos. They become experts at occupying no space.

Gibson 450 describes them as ‘emotionally orphaned’, physically present but psychologically alone. Praised for being ‘easy’ or ‘no trouble,’ but this praise reinforces invisibility. The message: your value lies in not existing too loudly. Your needs might inconvenience the narcissistic parent. Better to be a gap in the mirror than another fragment demanding attention.

Invisibility protects in childhood but creates problems in adulthood. Chronic feelings of emptiness and disconnection. Difficulty forming relationships, never having learned they can exist in relation to others. Patterns of self-isolation, disappearing when life becomes challenging. Many develop avoidant personality traits or schizoid adaptations, safety in solitude, longing for connection they do not know how to achieve. They have learned to be invisible so well that even they cannot find themselves.

The mascot uses humour and charm to deflect from dysfunction. Family entertainer, breaking tension with jokes, performing to distract from pain. The role appears lighter, but the mascot is never taken seriously, never allowed genuine emotion, never seen beyond the performance. Their reflection always performs—they have forgotten what stillness looks like.

The caretaker or enabler child, often the oldest, takes responsibility for managing the narcissistic parent’s emotions and maintaining family stability. Parent to siblings, therapist to mother, mediator in parental conflicts. Premature responsibility robs them of childhood while training them for a lifetime of codependency and over-functioning. They become the frame that holds the fractured mirror together: necessary, invisible, exhausted.

These forgotten children struggle to recognise their trauma because the neglect was less overt than outright abuse. They minimise their pain, feeling they have no right to struggle when siblings had it worse. In therapy, they begin sentences with “I know it wasn’t as bad as…” or “I shouldn’t complain because…” Comparative suffering keeps them stuck.

Healing for these children involves recognising that neglect is abuse, that invisibility creates its own trauma, that having needs is necessary for healthy functioning. They must learn to exist, to take up space, to matter. Terrifying for people who learned visibility meant danger, needs led to abandonment, and the safest place was no place at all.

The Inverted Mirror

When the Reflection Becomes the Source

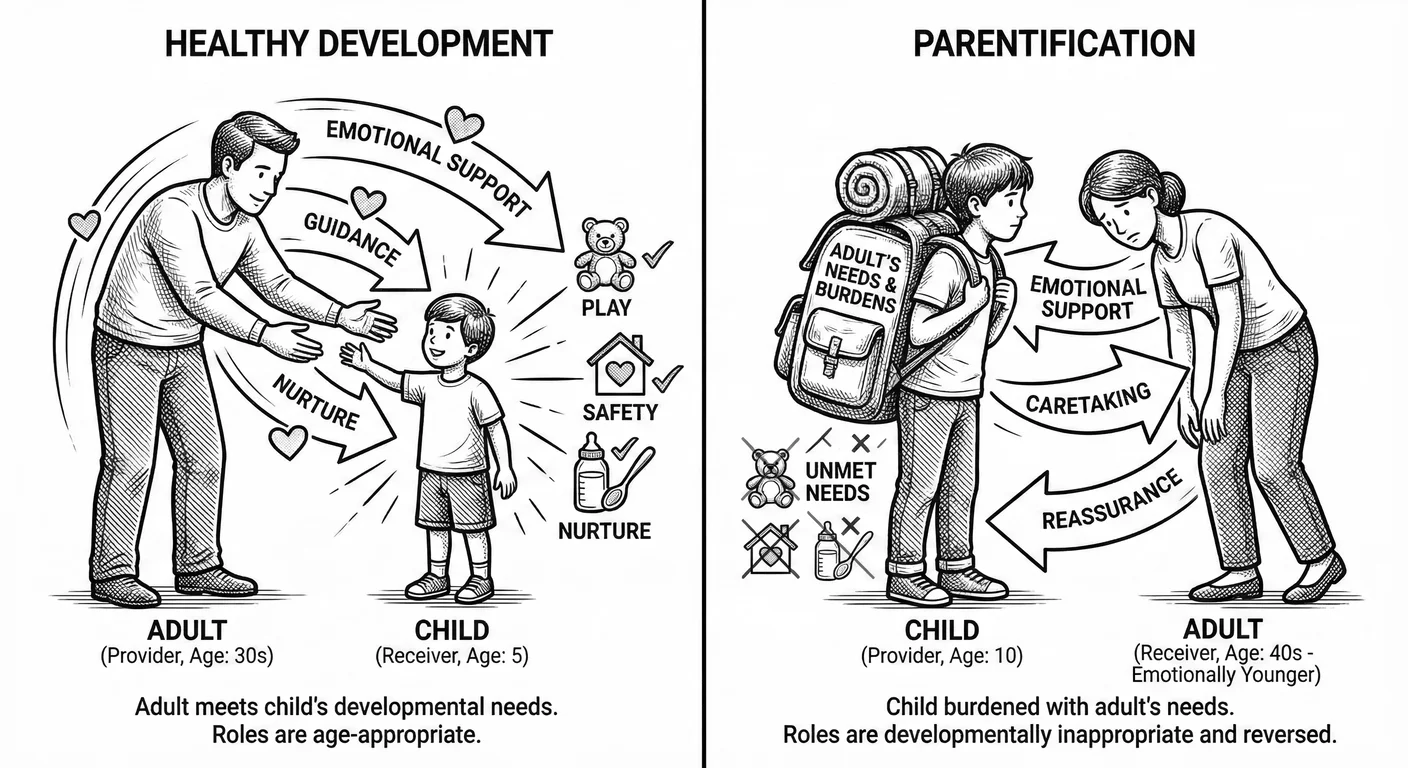

In healthy families, parents mirror the child, reflecting back their worth, helping them see themselves clearly. In narcissistic families, this process inverts. The child transforms into the mirror, reflecting the parent’s needs and emotional states. But parentification takes this inversion further: the child assumes responsibility for creating what the mirror shows—they do more than merely reflect the parent. They must generate the image the narcissist wants to see.

This role reversal often goes unrecognised because it masquerades as maturity or close family bonds. The child meets the parent’s emotional, physical, or psychological needs rather than receiving care themselves. They are robbed of developmental needs while burdened with responsibilities far beyond their capacity.

Parentification takes two forms: instrumental (physical tasks like cooking, cleaning, caring for siblings, managing finances) and emotional (becoming the parent’s confidant, therapist, emotional regulator). 623 In narcissistic families, both coexist, with emotional parentification being particularly severe.

‘Sexual parentification’ involves inappropriate emotional intimacy where the child fills the role of spouse or partner without any sexual abuse. 9 The narcissist shares details about their sex life, makes the child their primary emotional intimate, generating an enmeshed relationship that excludes the other parent. This is covert incest—a boundary violation as damaging as overt abuse.

Cultural factors shape how parentification is perceived. In many cultures, children contributing to household tasks is normalised and valued. The distinction between adaptive parentification—age-appropriate responsibilities building competence—and destructive parentification lies in the emotional dynamics: the child’s needs are consistently subordinated, their efforts unacknowledged. 569

Maria, thirty-eight, describes her experience: “By age eight, I was my mother’s therapist. She’d come into my room at night crying about my father, telling me things no child should hear. She’d ask what she should do, whether she should leave him, whether she was still pretty. I felt responsible for keeping her alive—she’d hint at suicide if I didn’t provide enough comfort. Meanwhile, I was failing third grade because I was too anxious and exhausted to concentrate. When the teacher called home, my mother was furious I was ‘making her look bad.’\thinspace”

The parentified child develops ‘pathological competence’, functioning beyond their years while masking serious developmental deficits. 358 Appearing mature and capable, earning praise from adults who do not recognise the cost. Inside, drowning, carrying burdens they lack resources to manage.

Neurobiologically, parentification disrupts brain development in ways paralleling other trauma. Chronic stress floods the developing brain with cortisol, impeding prefrontal cortex development. Neuroimaging studies demonstrate that emotional abuse and neglect, including parentification, reduce corpus callosum volume, affecting hemispheric integration and contributing to lifelong emotional dysregulation. 1217

The Living Mirror

The narcissistic parent’s emotional dependency on their child perverts the parent-child relationship. Healthy parents derive joy from their children; narcissistic parents depend on them for basic emotional regulation and supply. The child manages the parent’s moods, provides constant validation, and buffers against narcissistic injury. An impossible situation: the child possesses enormous power (the parent’s wellbeing depends on them) and no power (they cannot meet insatiable needs). The mirror must generate light rather than merely reflect it.

Nina Brown 163 describes how narcissists use children as ‘selfobjects’—extensions whose purpose is regulating the parent’s emotional states. When the parent feels empty, the child must provide fulfilment. When worthless, admiration. When angry, the child must absorb and metabolise that anger. A human emotional regulation device, expected to intuit and respond without being asked.

Narcissistic mothers intensify this selfobject exploitation, viewing children (especially daughters) as extensions of themselves. McBride 830 describes how these mothers create ‘emotional umbilical cords’ that are never cut. The daughter must remain perpetually available for the mother’s emotional needs, regardless of her own circumstances. Marriage, children, career, geographic distance: nothing interferes with the mother’s access to her daughter’s emotional labour.

When children fail to provide adequate emotional regulation, the narcissistic parent’s rage can be terrifying. Zaslav 1363 describes ‘narcissistic mortification’—a complete collapse of the grandiose self-image that feels like psychological death to the narcissist. The child who fails to prop up the parent’s ego, who does not respond quickly or enthusiastically enough, faces existential rage: threats of suicide, abandonment, violence, or days of silent treatment and verbal abuse. The message is clear: your failure to meet my emotional needs is an attack on my very existence. The mirror has failed to reflect glory, and so the mirror must be punished.

This dependency forges trauma bonds that persist throughout life. The oscillation between desperate dependency and cruel rejection generates addictive cycles. The child grows hypervigilant, constantly seeking approval that might bring temporary safety.

Adult children who served as emotional regulators struggle with codependency. They are drawn to emotionally needy partners, recreating the familiar dynamic. They feel guilty when inactive, anxious when others are upset, and responsible for everyone’s feelings except their own. The childhood pattern of self-erasure evolves into a lifelong template.

Frozen in the Frame

Parentification causes ‘developmental arrest’—normal psychological development stops or distorts at the point where adult responsibilities are imposed. The parentified child may develop capacities beyond their years, but core developmental tasks are skipped. The result: an adult highly functional in some areas while remaining frozen at the emotional age where childhood effectively ended.

Erik Erikson’s 360 stages of psychosocial development clarify what is lost. During school-age years, when children should develop industry through peer interactions and skill development, parentified children manage adult responsibilities. During adolescence, when identity formation should occur through experimentation and peer relationships, they remain locked in caretaking roles. These missed stages do not simply disappear; the adult continues struggling with tasks never completed.

Love and Stosny 763 describe ‘precocious maturity’—surface-level competence masking serious developmental deficits. These children discuss adult topics, manage complex responsibilities, present as far older than their years. Yet this represents a performance of adulthood without underlying emotional development. Inside, they remain the frightened children they were when parentification began.

The loss of play is particularly damaging. Brown 1196 , founder of the National Institute for Play, has demonstrated that play is essential for brain development, creativity, emotional regulation, and social skills. Play teaches children to manage relationships, develop imagination, experience joy. Parentified children, burdened with adult responsibilities, have neither time nor psychological space for play. Critical opportunities for neural development are missed.

Sibling relationships are deeply affected. If the parentified child raised younger siblings, they may struggle with resentment at having been forced into a parental role. Siblings may see them as authority figures rather than peers, creating distance that persists into adulthood. If the parentified child cared for the narcissistic parent while siblings had more normal childhoods, deep divisions within the family result.

Minuchin’s 872 structural family therapy identifies how parentification disrupts boundaries between family subsystems. In healthy families, clear boundaries exist between parental and child subsystems. In narcissistic families with parentification, boundaries are violated. A child may be elevated to the parental subsystem, creating coalitions against the other parent or siblings. This structural dysfunction patterns how the parentified child approaches relationships throughout life.

The Maze of Control

Gaslighting: When the Mirror Lies

Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. —see Chapter for full analysis—takes particular form with children. These children grow up in a funhouse mirror world where perceptions are constantly challenged, where they learn to doubt their own experience of reality.

Childhood gaslighting unfolds in three stages. 1184 First comes disbelief: the child senses something is wrong but cannot believe the parent would deliberately distort reality. Second comes defence: the child tries to prove their perception correct, gathering evidence, seeking validation. Third comes depression: the child gives up, accepting the parent’s version of reality. For children of narcissists, this process begins so early they may never have developed a solid sense of reality to defend.

Sarkis 1087 describes how childhood gaslighting creates ‘gaslight receptors’— Learned Helplessness Learned Helplessness A psychological state where repeated exposure to uncontrollable events leads to passive acceptance and belief that escape is impossible. in the face of reality distortion. These children become primed to accept gaslighting from partners and friends because it feels familiar.

Tariq, twenty-nine, describes growing up with a gaslighting father: “He would fly into rages, throwing things, screaming obscenities. The next day, he’d act like nothing happened. If we brought it up, he’d say we were imagining things. Once, he threw a plate at my mother and it shattered against the wall. Next morning, he convinced us the plate had fallen accidentally, that we were misremembering because we were upset. So convincing I started doubting my own memory. Maybe I had imagined it. I started keeping a journal, hidden, just to have proof that things actually happened. Even then, I’d read my own writing and wonder if I was making it up.”

Modern technology adds new dimensions to gaslighting. Parents can edit or delete digital evidence, manipulate photographs, create alternative narratives on social media contradicting children’s lived experience. Durvasula 338 describes cases where narcissistic parents have created entirely fictional family histories online—happy family photos and loving posts while engaging in abuse offline. Children see these digital artefacts and question their own memories.

The neurobiological impact is severe. van der Kolk 1272 explains that children need consistent, accurate mirroring of their experience to develop coherent neural networks for processing reality. When mirroring is systematically distorted, the brain develops fragmented, contradictory networks. The child may simultaneously know and not know something is true. This Cognitive Dissonance Cognitive Dissonance The psychological discomfort of holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously—common in abuse when the person harming you is also someone you love. creates chronic anxiety and contributes to dissociative disorders.

Recovery requires what Stern calls ‘reclaiming reality’, learning to trust perceptions again, often starting with basic sensory experiences. Therapy may involve describing what one sees and feels without interpretation, slowly building confidence. Many survivors find validation in journals or trusted friends who can confirm perceptions. The path from gaslit to grounded is long, requiring reconstruction of basic epistemic foundations. The funhouse mirrors must be replaced with clear glass.

Love Bombing: The Glittering Maze

Love Bombing Love Bombing An overwhelming display of attention, affection, and adoration early in a relationship designed to create rapid emotional dependency and attachment. creates trauma bonds through intermittent reinforcement (see Chapter for the neurobiology). During love bombing, periods of intense affection alternate with devaluation and neglect. The child becomes addicted to unpredictable moments of parental warmth, constantly seeking to recreate conditions that might bring about the next period of love.

During love-bombing phases, the narcissist showers the child with gifts, praise, attention, and grand promises. These periods often follow narcissistic injury or threat of abandonment: the child sets boundaries or shows independence, triggering fear of losing control. Love bombing re-establishes the trauma bond and pulls the child back into enmeshment.

The devaluation phase is equally calculated. Affection withdraws, criticism increases, rage erupts over minor infractions. The child, desperate to return to love bombing, tries everything—hypervigilant to the parent’s moods, constantly adjusting behaviour. Herman 546 calls this ‘coercive control’: the child regulates themselves more strictly than any external force ever could.

The impact extends beyond childhood. Adult children of narcissists find themselves in relationships replicating this pattern—drawn to partners offering inconsistent affection, mistaking trauma bond intensity for love. 788 Bored or suspicious in stable, consistent relationships because they have been programmed to equate love with unpredictability and constant effort to earn affection.

The Walls of Shame: Guilt and Obligation

The narcissist wields guilt and obligation like precision weapons, maintaining control and preventing autonomy. These manipulations are so embedded in family dynamics that children often do not recognise them as abuse, experiencing them instead as natural consequences of their own inadequacy. The acronym FOG—Fear, Obligation, and Guilt, coined by Susan Forward 407 —captures the atmosphere in which these children are raised. The fog fills the maze, making escape seem impossible.

A complex accounting system manufactures guilt, placing the child always in debt. Every sacrifice is tracked, every expense recorded, every moment of care presented as an unpayable debt. “After all I’ve done for you” echoes through every interaction. The child learns that their very existence is a burden for which they must constantly atone.

Brené Brown 166 distinguishes between guilt (‘I did something bad’) and shame (‘I am bad’). Guilt can be adaptive, aligning behaviour with values; shame is inherently destructive. Narcissists specialise in creating shame. They attack core worth—behaviour is an afterthought. “You’re selfish,” “You’re ungrateful”—these are condemnations of being, not criticisms of actions.

Shame creation begins early through multiple mechanisms. Nathanson 906 calls these ‘shame-humiliation cycles.’ The child is publicly embarrassed, compared unfavourably to others, mocked for feelings or needs. Private shaming may be more intense, secrets shared, privacy violated, vulnerabilities weaponised. The child learns that every aspect of themselves is potentially shameful.

Religious and cultural frameworks are exploited to intensify guilt. Religious concepts of sin, duty, and honour justify demands and condemn autonomy. ‘Honour thy father and mother’ weaponises itself against boundaries. Cultural values about family loyalty, filial piety, and respect for elders are twisted to serve the narcissist. The child seeking therapy or setting limits becomes cast as betraying faith, culture, and heritage—condemned for far more than disappointing a parent. The maze walls are built from history itself.

Wei, forty-one, from a traditional Chinese family, describes this cultural exploitation: “My mother used our culture’s emphasis on filial piety as a complete control mechanism. Any disagreement, any boundary, any pursuit of my own life was framed as betraying our ancestors, bringing shame on the family name. She’d say I was ‘too Westernised,’ that I’d forgotten where I came from. The guilt was crushing. How could I choose my own happiness over thousands of years of tradition? It took me years to realise she was using our beautiful culture as a tool of manipulation, that real filial piety doesn’t mean sacrificing your entire self.”

Obligation extends beyond normal responsibilities to encompass the child’s entire life. The demand is for sacrifice, never mere help; for prioritising the parent above all else, never simple care. It is non-negotiable and lifelong. The adult child must choose careers that please the parent, marry someone approved, raise children according to parental standards, and remain eternally available.

Payson 964 describes ‘loyalty binds’—situations where the child must choose between their own wellbeing and obligation to the parent: the parent threatening suicide if the child moves away, developing mysterious illnesses when the child starts dating, having financial crises whenever the child achieves success. These are impossible choices where self-care feels like betrayal.

Installing guilt and obligation creates what Rosenberg 1059 calls ‘self-love deficit disorder.’ The child believes their needs are inherently selfish, their boundaries cruel, their desire for autonomy betrayal. They have internalised the narcissist’s voice so completely they continue shaming themselves long after leaving home. The parent need not be present; the internalised FOG does the work automatically. The maze walls have become internal architecture.

Breaking free requires what Paul 958 calls ‘re-parenting’: learning to provide oneself with unconditional love and acceptance. This involves challenging internalised beliefs about worth, differentiating between healthy guilt and manipulated guilt, and building capacity to prioritise one’s own wellbeing without shame. The process takes years of therapy and support, as these manipulations are woven into the survivor’s identity.

What the Mirror Leaves Behind

Complex PTSD: The Shattered Self

Narcissistic parenting damages far beyond conventional PTSD. Herman 546 proposed Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) to capture symptoms from prolonged, repeated trauma in relationships where escape is impossible—exactly a childhood spent as a narcissist’s mirror. While PTSD typically follows discrete traumatic events, C-PTSD emerges from chronic developmental trauma shaping the very foundation of personality and self-concept. The mirror shatters, and fragments cut differently than a single break.

van der Kolk 1271 advocated for Developmental Trauma Disorder to address childhood trauma’s distinct impacts. Unlike a soldier developing PTSD after combat or an assault survivor, the child of a narcissist never had a stable self or safety to return to. The trauma is not an interruption of normal life—it is normal life. The developing brain and personality are shaped entirely within ongoing threat, creating pervasive alterations in consciousness, self-concept, and relational capacity.

Walker 1292 identifies Emotional Flashback Emotional Flashback A sudden regression to overwhelming emotions from past trauma, often without visual memories, experienced as intense feelings of helplessness, shame, or fear. s as a hallmark of C-PTSD—sudden regression to the emotional states of childhood trauma without visual or narrative memories. An adult child might feel small, powerless, terrified in response to triggers that seem minor to others. A critical comment from a boss might trigger the same physiological response as childhood experiences of parental rage. The old mirror-terror returns unbidden.

Freyd’s 421 Betrayal Trauma Betrayal Trauma Trauma that occurs when someone you depend on for survival or wellbeing violates your trust in a critical way. theory speaks directly to this dynamic. When trauma is perpetrated by someone the child depends on for survival, the psyche must perform extreme adaptations to maintain attachment. The child cannot fight or flee, so they fragment their awareness, simultaneously knowing and not knowing about the abuse. Freyd calls this ‘betrayal blindness’—inability to fully perceive or acknowledge trauma that allows the child to maintain necessary attachment.

Rachel, thirty-seven, describes her symptoms: “I didn’t understand why I couldn’t function like other people. Panic attacks in meetings if someone seemed disappointed. I’d dissociate during conflicts, feeling like I was floating above my body. Chronic insomnia, always hypervigilant, waiting for danger. My therapist explained that my nervous system was still operating like I was living with my mother, constantly scanning for threat, never able to relax. No-contact for five years, but my body hadn’t gotten the message.”

Somatic symptoms are extensive and often misattributed. Levine 726 explains that trauma is stored in the body, creating chronic muscular tension, digestive problems, and chronic pain. Research has linked childhood adversity to increased rates of autoimmune conditions and other physical health problems in adulthood 1272 . The body keeps score, as van der Kolk says, long after the conscious mind has tried to forget.

Neurobiological research demonstrates extensive brain changes. Teicher 1217 found reduced hippocampal volume (affecting memory consolidation), alterations in the corpus callosum (affecting hemispheric integration), changes in the prefrontal cortex (affecting executive function and emotional regulation). Measurable neurobiological alterations from chronic developmental stress, beyond mere psychological symptoms. The narcissist’s abuse literally reshapes the child’s brain.

Seeking Familiar Reflections

Repetition compulsion—the unconscious drive to recreate unresolved traumatic experiences—manifests powerfully in relationship patterns of adult children of narcissists. Despite conscious desires for healthy relationships, they find themselves drawn to partners who replicate their narcissistic parent’s dynamics. Deeply programmed neural pathways and attachment templates formed in childhood, never masochism or stupidity. They seek familiar reflections, even painful ones.

Hendrix 542 explains through Imago Relationship Theory that we are unconsciously drawn to partners embodying both positive and negative traits of early caregivers. For children of narcissists, attraction follows to partners offering familiar combinations: intermittent affection, emotional unavailability, the promise that with enough effort, love might be earned. Trauma bonding’s intensity is mistaken for passion, dysfunction’s familiarity for destiny.

Patterns vary by childhood role. Former golden children seek partners who idealise them, recreating conditional admiration. Former scapegoats are drawn to critical, blaming partners confirming internalised defectiveness. Former lost children choose partners who ignore them, recreating invisibility. Former parentified children become involved with partners needing caretaking, continuing as emotional regulators.

Rosenberg 1059 describes the ‘human magnet syndrome’—magnetic attraction between codependents (often adult children of narcissists) and narcissists. The dysfunction is complementary, never coincidental. The adult child has been programmed to prioritise others’ needs, earn love through service, tolerate abuse. The narcissistic partner seeks someone providing unlimited supply without requiring reciprocity. Each triggers the other’s familiar patterns.

Sophia, thirty-three, describes her relationship history: “Every relationship was the same story with different actors. I’d meet someone charming and confident, so different from how I felt inside. They’d love-bomb me, and I’d feel chosen, finally worthy. Then devaluation would start. Criticism, coldness, gaslighting. I’d work desperately to get back to the initial phase, convinced it was my fault. Three relationships following the exact same pattern before I realised I was choosing my mother over and over, just in different bodies.”

Breaking patterns requires more than awareness. Siegel 1141 explains that early attachment experiences create neural highways that become default routes for processing relational information. The adult child may cognitively understand they are repeating patterns, even identify red flags, but childhood neural pathways override conscious intention. The familiar feels safe even when objectively dangerous because the nervous system equates familiar with survivable.

Fear of healthy relationships is common. When adult children of narcissists encounter genuinely caring, consistent partners, they experience intense anxiety. The absence of drama feels like absence of love. Consistent affection triggers suspicion. Genuine empathy feels suffocating or false. Many sabotage healthy relationships, unconsciously creating familiar conflict and distance. Katehakis 636 describes this as ‘intimacy disorder’—inability to tolerate the vulnerability of being truly seen, beyond mere fear of closeness.

The Missing Self

Coherent, stable identity requires consistent mirroring and freedom to explore different aspects of self. Children of narcissists, denied these experiences, often reach adulthood with what Masterson 817 calls ‘impaired real self.’ They may have a highly developed false self, the adaptation created to survive, but little access to authentic identity. Having served only as a mirror, they never developed a self to reflect.

Chronic emptiness, distinct from depression, is common. Void rather than sadness: a sense that nothing exists at the centre, no solid self to return to. Kernberg 649 calls this ‘identity diffusion’—lack of integrated self-concept leaving the person feeling fragmented and unreal. They may feel like different people in different contexts, unable to maintain consistency across relationships and situations.

Imposter syndrome reaches pathological levels. Despite external achievements, they feel fraudulent, constantly fearing exposure as inadequate. Clance 250 , who coined the term, notes imposter syndrome intensifies particularly in those whose childhood achievements were dismissed or claimed by others. The adult child who was never seen cannot internalise accomplishments as real or deserved. Success feels accidental, precarious.

Inability to identify wants and preferences marks identity disruption. Gibson 450 describes adult children asking ‘What do I want?’ and drawing a complete blank. Years of suppressing desires in favour of managing the narcissist’s needs have disconnected them from their internal compass. They make decisions based on what others expect, what looks good, what they think they should want—never accessing authentic desire.

Kevin, forty-two, describes his confusion: “I realised at forty that I had no idea who I was. I could tell you who I was supposed to be, successful lawyer, good husband, devoted son. But who was I really? What did I actually enjoy? What were my values versus what I’d been programmed to value? My therapist asked me to describe myself without referencing roles or achievements. Twenty minutes, and I couldn’t come up with a single thing. Terrifying to realise I was a stranger to myself.”

The chameleon self, unconsciously adapting to others’ expectations, evolves into a survival strategy that persists into adulthood. Adult children of narcissists excel at reading others and becoming what others need, but at the cost of authentic self-expression. They become different people with different friends, partners, colleagues—automatic adaptation learned where being authentic was dangerous, never conscious manipulation.

Schwartz’s 1106 Internal Family Systems model helps explain this fragmented identity. The model describes highly developed ‘manager’ parts maintaining control, ‘firefighter’ parts numbing pain, and ‘exile’ parts: young, wounded aspects holding the pain of never being seen or loved. Healing involves accessing what Schwartz calls the ‘Self’, the core, undamaged essence existing beneath protective adaptations—the person behind the mirror, finally allowed to emerge.

Mental Health Consequences

Narcissistic parenting causes damage to mental health far beyond what single diagnoses can capture, manifesting as complex comorbidities reflecting pervasive developmental trauma. Adults with histories of childhood emotional abuse and neglect show higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, and personality disorders than those with histories of physical or sexual abuse alone. 1165 Invisible wounds create visible psychiatric symptoms that often persist despite traditional treatment.

Depression in these adult children has distinct features. Anderson 30 calls it ‘abandonment depression’, a core belief about being utterly alone and unlovable, far deeper than sadness. The internalised voice of the narcissistic parent continues the abuse internally: “You’re not good enough,” “You don’t matter.” Antidepressants may lift mood somewhat; the underlying sense of defectiveness persists without trauma-informed treatment.

Anxiety disorders are nearly ubiquitous, but the anxiety has specific features. Rutherford 1068 identifies ‘perfectly hidden depression’—high-functioning anxiety masked by perfectionism and achievement. These individuals appear successful while experiencing intense internal turmoil. The anxiety triggers specifically in situations reminiscent of childhood: criticism, conflict, disappointing others, any situation requiring authentic self-expression.

Eating disorders develop as attempts to manage unmanageable feelings. Zerbe 1366 notes they serve multiple functions: control when everything else feels chaotic, numbing of emotional pain, perfectionism in at least one domain, rebellion against the narcissistic parent’s control. The body transforms into the battlefield where the struggle for autonomy plays out.

Substance abuse as self-medication is common, often hidden behind high functionality. Adult children learn early that feelings are dangerous. Alcohol and behavioural addictions become ways to regulate the dysregulated nervous system, to escape the internalised critical voice 120 . The addiction is a symptom masquerading as the problem of living with C-PTSD, a distraction, until a solution presents itself.

Some develop personality disorders; borderline and narcissistic personality disorders are the most severe consequences. These are adaptations to severe attachment trauma, distinct from psychiatric conditions. Some adult children identify with the aggressor, developing narcissistic traits as protection against ever being vulnerable again. Others develop borderline patterns, desperately seeking the love they never received while simultaneously fearing abandonment and engulfment.

Linehan 748 notes that chronic invalidation in childhood, a hallmark of narcissistic parenting, is a primary risk factor for self-injurious behaviour. Self-harm may serve multiple functions: making internal pain visible, punishing the self for perceived inadequacy, feeling something rather than nothing, or attempting to regulate overwhelming emotions. Suicidal ideation may be less about wanting to die than about ending unbearable psychological pain or escaping from a self that feels deeply flawed.

These consequences interact in what Briere 159 calls ‘complex comorbidity’: multiple, interrelated conditions that cannot be treated in isolation. The depression feeds the anxiety, which triggers the eating disorder, which necessitates the substance use, all underlain by C-PTSD and identity disturbance. Treatment must address the underlying developmental trauma, beyond mere symptoms; the internalised relationship with the narcissistic parent, beyond mere brain chemistry that continues long after physical separation.

From Mirror to Person: Recovery and Healing

The Awakening

Healing begins with what survivors describe as ‘the awakening’, the moment when they finally recognise that their childhood was not normal, that their parent’s behaviour was abusive, that they are injured by someone who should have protected them, never defective at their core. The mirror finally sees itself. This recognition, while liberating, triggers a psychological earthquake shaking the foundations of identity and worldview. Everything they thought they knew about themselves, their family, their place in the world suddenly requires re-examination.

McBride 830 describes this recognition as both devastating and essential. The adult child must confront what she calls ‘the three deaths’: the death of the fantasy parent they always hoped for, the death of the idealised childhood they tried to believe they had, and finally the death of the false self they constructed to survive. This triple mourning process is necessary for healing but intensely painful. Many survivors describe feeling more depressed initially after recognition than they did while still in denial.

Recognition comes through many paths. Some adult children stumble upon a book, article, or online forum describing narcissistic parenting and immediately recognise: ‘This is my parent; this is my life.’ Others enter therapy for seemingly unrelated issues—depression or relationship problems—and slowly uncover narcissistic abuse underlying their symptoms. Still others do not recognise the abuse until they have their own children and realise they would never treat a child the way they were treated.

Angela, forty-five, describes her moment of recognition: “I was watching my daughter play, and she spilled juice on her dress. I started to react the way my mother would have—rage and shame, making her feel worthless over a simple accident. I caught myself and realised I was about to perpetrate the same abuse. That night, I googled ‘why do I feel worthless’ and found an article about narcissistic mothers. I read it and sobbed for hours. It was like someone had been watching my childhood and writing about it. For the first time, I realised it wasn’t me. I wasn’t bad or defective. I had been abused.”

Finding language for the experience is essential for healing. Many adult children have spent decades unable to articulate what was wrong with their childhood. They might say, ‘My parents were difficult,’ or “We didn’t get along,” but these phrases do not capture the systematic psychological abuse they endured. Learning terms like ‘gaslighting’ and ‘trauma bonding’ offers a vocabulary that makes their experience real and communicable. Language transforms wordless pain into something that can be examined and ultimately healed.

Online communities have revolutionised the validation process for adult children of narcissists. Support groups and social media communities provide what Herman 546 identifies as essential for trauma recovery: bearing witness. When survivors share their stories and hear others’ similar experiences, the isolation and self-doubt that narcissistic abuse creates begins to dissolve. The gaslighting that made them question their reality is countered by hundreds of voices saying, “This happened to me too. You’re not crazy. It was real.”

Durvasula 338 warns about the potential pitfalls of online spaces. While validation is healing, some communities can become stuck in victimhood, endlessly rehearsing grievances without moving towards recovery. Others may engage in armchair diagnosis, labelling everyone who hurts them as narcissistic. The most helpful communities balance validation with growth, acknowledging the abuse while focusing on healing and building healthier lives.

Grief following recognition is complex and nonlinear. Elisabeth K”ubler-Ross’s stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—all apply, but not in neat sequence. Boss 141 adds ‘ambiguous loss’: grieving someone who is still alive but psychologically absent. The narcissistic parent never truly existed as the child imagined them; the loving parent was a fantasy the child created to survive. Grieving someone who never existed, someone you desperately needed, is a particular form of sorrow.

Therapeutic Approaches

Traditional talk therapy often proves insufficient for developmental trauma from narcissistic parenting. The damage exists in the body, the nervous system, the core structures of identity—far beyond thoughts and emotions. Effective treatment requires what van der Kolk 1272 calls ‘bottom-up’ approaches, addressing the physiological imprints of trauma as well as cognitive processing (Chapter 18 provides full coverage of therapeutic modalities for narcissistic abuse recovery).

Therapeutic approaches suited to adult children of narcissistic parents include EMDR (detailed in Chapter ), which Parnell 955 adapted for this population through resource installation before processing traumatic memories. Internal Family Systems (see Chapter ) offers a framework for healing the fragmented self, addressing the young parts frozen at different developmental stages. Somatic approaches (Chapter ) rebuild the body connection that developmental trauma severed.

Group therapy offers specific benefits for those isolated by shame and family secrets. Discovering others with similar experiences is deeply healing; groups provide opportunities to practice new relational patterns with peers who understand the struggle.

A caution: Not all therapeutic approaches are helpful, and some can be harmful. Payson 964 warns against therapists who push premature forgiveness, minimise emotional abuse, or encourage continued contact with abusive parents without adequate boundaries. Family therapy with a narcissistic parent often becomes another venue for manipulation and abuse. Therapists unfamiliar with narcissistic abuse may inadvertently recreate damaging dynamics, siding with the charming narcissistic parent against the ‘difficult’ adult child.

Boundaries and No-Contact Decisions

Setting boundaries with narcissistic parents represents one of the most challenging aspects of recovery. Chapter 16 provides detailed tactical guidance on boundary-setting, Grey Rock, and no-contact implementation; here we address the particular psychological challenges adult children face when setting limits with parents.

These parents systematically trained their children that boundaries are cruel and unacceptable. The adult child attempting to establish limits faces external resistance from the parent compounded by intense internal resistance from their own conditioning. Every boundary feels like betrayal, every limit like abandonment of the parent who, despite everything, they still love and long to please.

Cloud and Townsend 255 define boundaries as ‘property lines’ marking where one person ends and another begins. For adult children of narcissists, no one ever established these lines, or parents repeatedly violated them. The work of recovery involves first recognising the right to have boundaries, then setting them, understanding that saying no, having needs, and protecting oneself are acceptable and indeed necessary for psychological health.

Going ‘no contact’ (completely cutting off communication with the narcissistic parent) increasingly gains recognition as a valid and sometimes necessary step for healing. Campbell 195 argues that when a parent is consistently harmful and shows no capacity for change, maintaining contact perpetuates trauma. No contact is self-protection, never punishment or revenge; it is like avoiding contamination or staying away from contagious disease.