When the capital development of a country transforms into a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.

— —John Maynard Keynes

Introduction

Leon, thirty-four, worked in a fulfilment centre in the United Kingdom for three years. We meet in a pub near his flat; he has been out for six months now, on disability for a back injury. “The thing is, I was good at it.” He says this twice during our conversation. “Top picker three months running. They put my photo on the wall.” He shows me a picture on his phone: himself in a high-vis vest, grinning, holding a certificate. “Fifteen minutes for toilet breaks, and that included the walk. If your rate dropped, you got written up. I never got written up. I was proud of that.” He puts the phone down but keeps glancing at it. “After the injury, my manager said they’d find me something. Lighter duties, he said. Then nothing. Three weeks, nothing. I kept calling. Eventually someone in HR told me my position had been eliminated.” He picks up his pint, puts it down without drinking. “My wife says I still check my rate in my sleep. She says I mutter numbers. I don’t remember that. But sometimes I wake up and I’m already calculating how many items I need to make target, and then I remember there’s no target anymore, and I don’t know if that’s better or worse.”

After family, our work is the major source of life experience for most of us. The study of “corporate psychopaths” began with a simple observation: some organisations become toxic regardless of market conditions, strategy, or external pressures. 132 The common factor was leadership—specifically, leaders who scored highly on measures of what psychologists call the Dark Triad Dark Triad A constellation of three overlapping but distinct personality traits: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. These traits are associated with manipulation, exploitation, and harmful interpersonal behavior. : narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy.

The research built on earlier work by Paul Babiak and Robert Hare, whose “Snakes in Suits” 60 documented how individuals with psychopathic traits move through corporate environments by excelling at the impression management essential to advancement. The question is not whether narcissistic traits appear in business leadership (they demonstrably do), but what happens when such traits become concentrated in positions of power.

Dr Manfred Kets de Vries, a psychoanalyst and professor at INSEAD business school, has spent four decades studying executive psychology. His work identifies what he calls “productive narcissists”: leaders whose grandiosity and vision can drive innovation. 307 Steve Jobs, by many accounts, displayed narcissistic traits: he had grandiose vision, and treated employees as extensions of his will. Yet Apple evolved into the world’s most valuable company. The question Kets de Vries poses is not whether narcissistic leaders can succeed (clearly they can), but at what cost, and for how long?

The costs are measurable. Bennett Tepper’s work on “abusive supervision” 1220 documented the psychological and physical health consequences for employees under hostile leaders: increased depression and cardiovascular problems; decreased job satisfaction and productivity. The abuse was not incidental to the leadership style but intrinsic to it. The same traits that projected confidence in boardrooms created terror in subordinates.

A narcissistic leader does not just create an unpleasant workplace but actively damages employees’ psychological functioning 132 . The exploitative dynamics of the narcissistic parent explored in Chapter —especially the idealisation and devaluation—replicate in organisational settings. For those with histories of narcissistic abuse, the workplace can and will become a site of retraumatisation. For people without such histories, it can be where they first learn these dynamics, often without recognising what is happening until significant damage is done.

What changes is the overall scale. The narcissistic parent damages their family; the pathological CEO can damage thousands of employees and, in extreme cases, destabilise entire economies.

Multi-level theory in organisational behaviour demonstrates that psychological constructs can be “isomorphic across levels”—displaying the same content, meaning, and structure whether they emerge in individuals, teams, or entire organisations. 671 The narcissistic patterns explored at the individual level in Chapter —the defensive structures, the false self, the inability to tolerate authentic connection—appear with structural fidelity at company, and corporate scale. Duchon and Burns identified “organisational narcissism” as a measurable construct with the same core features as individual NPD: grandiosity, self-admiration, entitlement to recognition, and exhibitionism. 333 The diamorphic choice that faces every developing individual—authentic growth versus defensive rigidity—faces organisations as well. The corporation that cannot tolerate criticism, which demands loyalty over competence, and treats employees as extensions of leadership’s will has made the same choice as the narcissistic personality: a false self, scaled up to become a harvesting operation, dispensing with real empathy.

To recap the framework from Chapter : diamorphic agency describes the developmental fork where, faced with overwhelming threat to the emerging self, the individual either integrates the experience and continues authentic growth, or constructs defensive structures that sacrifice authenticity for protection. The narcissistic personality represents the second path—a false self built for the public to manage expectations from an insufficient reality, maintained through grandiosity, denial, and exploitation of others as sources of supply.

At organisational scale, the same fork appears. The startup facing market rejection can integrate the feedback and adapt by providing reliable solid value (authentic development), or construct an elaborate reality-distortion field that insists the market simply fails to recognise its genius (defensive rigidity) which becomes a mask over exploitation and amoral harvesting.

The corporation receiving criticism can examine its practices and change (authentic development) by paying a real cost in return for providing real value and additional hard earned credibility going forward. Alternatively, and commonly it may deploy legal teams, PR campaigns, and internal purges to silence critics and maintain its increasingly false public-image (defensive rigidity).

The developmental trajectory is identical: early threats produces defensive adaptation; defensive adaptation becomes entrenched structure; entrenched structure produces the characteristic patterns of exploitation, denial, and rage at perceived injury. What authentic corporate development looks like is visible in companies that can acknowledge error, tolerate dissent, treat stakeholders as ends rather than means, and derive identity from actual contribution rather than an approval narrative. Such organisations exist; they are simply less dramatic than their pathological counterparts, and thus less visible in any business press that rewards spectacle over substance.

The Hidden Epidemic: HR Complaints as NPD Manifestations

Claire, forty-two, spent twelve years in HR at a mid-sized insurance company in Chicago. We meet at a café she chose because it is far from her old office. “I was good at the job. That’s what I can’t get past.” She stirs her coffee without drinking it. “The complaints kept coming back to the same names. Same directors. Same patterns. I’d document everything, escalate it properly. Sometimes I’d even get someone moved to a different team. I thought that was a win.” She stops stirring. “There was this woman, Beverley. She came to me *three times *about her manager. I moved her twice. The third time, I told her maybe she should think about whether the role was right for her. I said it kindly. I thought I was being realistic.” She looks at the spoon in her hand as if she has forgotten what it is for. “Beverley took a package six months later and I processed the paperwork. I remember thinking: well, at least that’s resolved. I didn’t think about what ‘resolved’ meant for her. I thought about the file being closed.” She left eighteen months ago. She does not say where she works now, and I do not ask. “I looked Beverley up on LinkedIn last year. She’s a teaching assistant now. I don’t know if that’s what she wanted or what she ended up with. I think about her more than I should.”

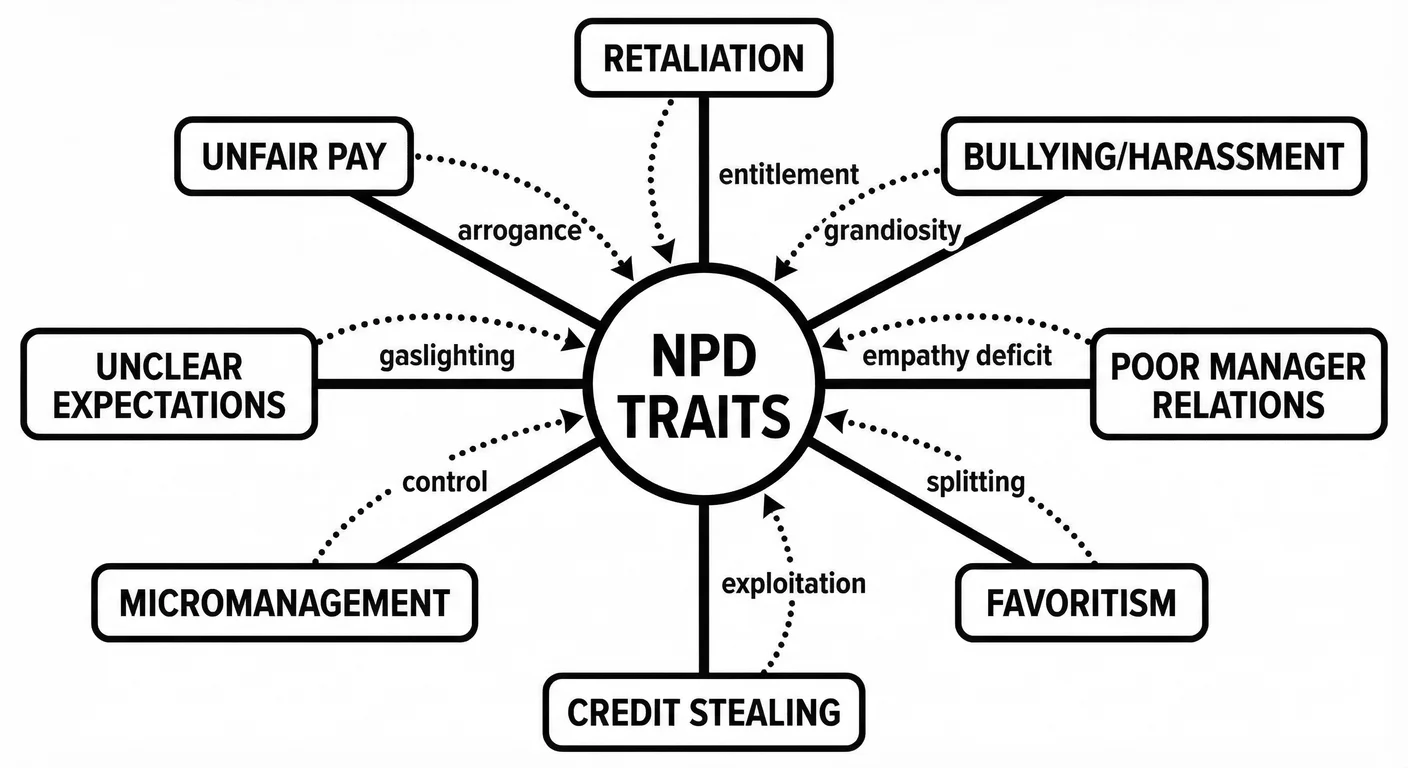

Another pattern that warrants further investigation: major categories of workplace complaint map suggestively onto traits associated with Narcissistic Personality Disorder. This interpretive framework emerges from examining research that has lived in institutional silos—clinical psychology studies NPD diagnostically, organisational behaviour studies “toxic leadership” without clinical framing, and HR/legal systems track complaints as discrete incidents rather than personality-driven patterns. The mapping below is offered as a suggestive synthesis, not an empirical finding; rigorous validation would require controlled studies that have not yet been conducted. Nevertheless, the parallels are striking enough to merit consideration as they could prevent future harm to employees.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives approximately 90,000 charges of workplace discrimination annually, with retaliation constituting over half of all cases—the most common complaint every year since 2008 352 . XpertHR surveys found that 67% of employee grievances cite bullying or harassment, 54% cite relationships with managers, and 37% cite unfair pay and grading. HR Acuity’s analysis of 284 organisations representing 8.7 million employees found claims of discrimination and harassment at their highest recorded level: 14.7 per 1,000 employees.

When these complaint categories are mapped to DSM-5 NPD criteria, parallels appear:

-

Retaliation (52% of EEOC cases) manifests narcissistic rage and entitlement—punishment for boundary-setting

-

Bullying/harassment (67% of grievances) manifests grandiosity and empathy deficit—dominance display and devaluation

-

Poor manager relationships (54%) manifests arrogance and exploitation—treating subordinates as supply sources

-

Favouritism manifests splitting—the golden child/scapegoat dynamic scaled to teams

-

Credit stealing manifests grandiosity and entitlement—“Their work is my work”

-

Micromanagement manifests control and grandiosity—“Only I know how to do it right”

-

Unclear expectations manifests gaslighting—moving goalposts to maintain plausible deniability

-

Unfair pay manifests exploitation—hoarding resources while devaluing others’ contributions

The most troubling finding concerns retaliation itself. The number one workplace complaint is simultaneously the narcissistic response to complaints—creating a suppression spiral. An employee experiences narcissistic abuse and complains; the leader retaliates (narcissistic rage at perceived challenge to authority). Other employees observe and stop reporting. The system designed to address abuse instead enables it. Research confirms that 65% of workplace bullies are bosses 1307 —those with power over targets and protection from consequences.

If this holds, HR systems may be treating symptoms rather than causes. High complaint volumes might indicate pathological leadership patterns rather than “problem employees”—though toxic workplace dynamics can also emerge from structural factors like under-resourcing, poor training, or industry norms independent of individual personality. The parallels between clinical and HR taxonomies warrant systematic investigation; the patterns that manifest in families and relationships may appear in workplace data at significant scale.

Narcissism in Leadership

Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—introduced in Chapter clusters in corporate leadership at rates far exceeding baseline prevalence 961 . While psychopathy affects approximately 1% of the general population, it may be present in 4-12% of senior executives 959 132 . The selection mechanisms are built into modern corporate structures: narcissists’ confidence aligns with cultural stereotypes of leadership 1228 ; Machiavellians excel at organisational politics 332 ; psychopaths’ “fearless dominance” 1112 allows brutal decisions that more empathetic leaders might struggle with.

This convergence creates what researchers call “corporate psychopaths”: individuals who regards companies as vehicles for personal gratification without regard for consequences 132 . While narcissists seek admiration, Machiavellians seek power, and psychopaths seek thrills, the combination pursues all three simultaneously through organisational exploitation 617 . The narcissistic grandiosity apparently provides vision, the Machiavellian cunning appears to provide strategy, and the psychopathic callousness results in execution without conscience. These enhance the narcissistic and psychopathic traits of the organisation.

These patterns appear wherever power concentrates without accountability. The family restaurant where the patriarch chef screams at staff, throws plates, and takes credit for dishes his sous chef created, while food critics praise his “passion.” The art gallery owner who cultivates young artists with promises of shows and introductions, extracts their best work at exploitative rates, then drops them the moment a more fashionable name appears. The fourth-generation farm where the patriarch cannot retire, cannot share decision-making, cannot acknowledge that his children might have ideas worth hearing, so the children leave, one by one, until there is no one left to inherit what he refused to share.

Family businesses show Dark Triad traits particularly concentrated, and particularly destructive 132 . The family firm combines the worst features of dysfunctional families and exploitative corporations: inescapable relationships and weaponised inheritance, the myth of shared purpose masking exploitation. When the boss is also your father, when the office is also the dinner table, when quitting means losing not just a job but a family, these dynamics reach their most suffocating form.

Priya, forty-one, is the middle child in a family that has run a chain of electronics stores in the Midlands for three generations. We meet at a hotel lobby in Birmingham, neutral territory, she says, where she will not run into relatives. She is dressed in the careful professional attire of someone who learned early that appearance is armour. Her hair is tied back, her glasses thin rimmed, and her office suit immaculate and professionally grey. She sits and doesn’t waste time with pleasantries. “My grandfather started with one shop in 1962. My father turned it into twelve. I was supposed to be grateful, to take my place, to continue the legacy.” She stirs her coffee but does not drink it. “I was smarter than my brothers. Everyone knew it. I got a first at the London School of Economics abroad while they scraped through community college. But Dad made my older brother CEO because he was the eldest son. He then made my younger brother CTO because he was the baby. He then made me ‘customer experience manager’, and told me to make sure they succeeded. It was a title he invented that meant I did the work while they took the credit.”

The patterns she describes match the research precisely. “My father would praise me in private, ‘You’re the only one with any sense’, then humiliate me in board meetings. He’d promise shares that never materialised. He’d threaten to write me out of the will if I challenged him, then act wounded when I was distant at family dinners. My brothers learned from him. They’d take my ideas to him directly, present them as their own. When I complained, I was ‘too emotional,’ ‘not a team player,’ ‘ungrateful for everything the family had given me.’ The family and the business were the same thing. Criticise one and you betrayed both.”

She left. Three years ago; forfeiting her inheritance claim. “My mother still doesn’t speak to me. My brothers tell people I had a ‘breakdown’. My father told the local paper I was ‘pursuing other opportunities with the family’s blessing.’ None of it’s true but the family controls the narrative. I lost the business, the money, the relationships. But I also lost the panic attacks, the insomnia, the feeling that I was going insane. It took a while, and I had to be out of their range but I started my own consulting firm. It’s far smaller than what I walked away from. But it’s mine. And nobody can take it from me by changing a will or calling a board meeting.”

If Priya’s experience seems familiar, it highlights the scapegoating dynamics of narcissistic family systems. In her family, she played the role of a capable child whose competence threatened the preferred hierarchy: eldest son as heir, youngest as beloved baby, daughter as support staff. Her father’s private praise and public humiliation mirrors narcissistic Splitting Splitting A psychological defence mechanism involving all-or-nothing thinking where people or situations are seen as entirely good or entirely bad, with no middle ground. : she was both indispensable (“the only one with sense”) and expendable (excluded from real power). The gaslighting she describes (being called “too emotional” for noticing her own exploitation) is textbook cultural gaslighting, scaled from family dinner to boardroom. And the smear campaign after her departure (“she had a breakdown”) follows the narcissistic playbook precisely: when the scapegoat refuses to carry the family’s dysfunction, they must be discredited to protect the system’s self-image.

Consider Jeffrey Skilling, a man convicted of multiple federal felonies for his role in Enron’s historic collapse. Court documents paint a portrait of grandiosity that transformed a gas pipeline company into “the world’s leading company”, at least on paper. Prosecutors described financial structures designed to deceive, and a callousness that allowed thousands of employees’ retirement savings to evaporate. The jury found a company officer who treated others as instruments, the rules as obstacles, and truth as negotiable. The pathological pattern was not incidental to Enron’s fraud; it was, prosecutors argued, the engine driving it.

Grandiose officers are attractive because they can initially generate positive outcomes: their apparent confidence inspires followers and their risk-taking drives short term growth. 1120 Researchers call this the “bright side of the dark side”—immediate benefits that mask long-term destruction. Organisations focused on quarterly earnings and these immediate results often fail to recognise the accumulating damage until failure occurs.

The ongoing impact on employees is substantial. Tepper’s research found that abusive supervision—usually involving ridicule, public humiliation, blame-shifting, scapegoating—leads to emotional exhaustion, lower job and life satisfaction, and causes higher work-family conflict. 1220 Employees under such leaders experience increased depression and physical health problems. Workplace bullying, often perpetrated by Dark Triad leaders, affects not just direct targets but witnesses, creating cultures of fear that suppress collaboration and ethical behaviour. 768 For employees attracted by the apparent security and professionalism and success of the public image, the company’s daily toll quickly turns their lives into a grim parody of itself.

Narcissistic CEOs create “cultures of narcissism”—entire organisations that adopt the leader’s grandiose self-concept. 371 The company’s mission becomes inseparable from the narcissist’s ego; meaning any questioning the leader becomes a punishable betrayal of the organisation. The result is what Jerry Harvey in 1988 called “the Abilene Paradox”: internal groups taking actions contrary to their members’ individual beliefs because everyone assumes others support the leader. 527

Mark, forty-seven, spent fifteen years as a vice president at a Fortune 500 pharmaceutical company. We meet at a coffee shop in Princeton; he is now consulting, which he describes as “the polite term for unemployable after what happened.” “The CEO was incredibly charismatic in public—people would cry during his speeches about curing diseases. But in private, he’d always pit us against each other, while spreading rumours to keep us off-balance and competing for his favour.” He pauses. “The scariest part was watching him fire people. Complete lack of emotion. He’d terminate someone who’d given twenty years and was in his words Family, walk them to security, then casually go to lunch at the executive dining room. Order the salmon. I saw it three times.” His voice drops. “We all knew something was off but we each only saw parts of it. He was very good at it, you see. He’d isolated us so effectively that none of us trusted each other enough to compare notes until it was too late. By the time it collapsed—accounting irregularities, FDA violations, whistleblower lawsuit—he’d parachuted out with $50 million. The rest of us? Worthless options, stained reputations due to the quagmire, followed by years of depositions. I still have nightmares about that dining room. The salmon.”

The salmon detail haunts Mark because it revealed the psychopathic dimension: the complete absence of emotional response to causing harm. The signals are often performative to heighten the sense of threat, and therefore increase psychological leverage. The CEO’s deliberate isolation of executives mirrors Triangulation Triangulation A manipulation tactic where a third party is introduced into a relationship dynamic to create jealousy, competition, or to validate the narcissist's position. —the narcissist’s strategy of disrupting information flow to prevent alliances. Mark did not just lose a job; he lost the career narrative that had formed his adult identity.

The rise of “CEO activism” and “purpose-driven leadership” has created new venues for Dark Triad expression. Dr Craig Johnson 613 describes how grandiose leaders co-opt social causes for self-promotion, what he calls “virtue signalling leadership.” They publicly champion popular causes while privately engaging in contradictory behaviour. The Machiavellian calculates which positions generate maximum positive publicity with minimum actual commitment. The psychopath feels no genuine concern for causes but recognises their public relations value. The deception is particularly insidious—leaders who appear moral while being deeply amoral.

Toxic Workplace Cultures

Callum, twenty-nine, worked his way up from commis chef to sous chef at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Edinburgh. His hands still bear the scars—cuts, burns, the permanent calluses of the trade. “I still cook his recipes at home sometimes.” He says this without irony. “The man was a —-, but he was brilliant. You can’t take that away from him.” He turns his coffee cup in circles on the table. “He threw things. Plates, pans, whatever was nearest. Called people things I won’t repeat. I saw him reduce a sixty-year-old porter to tears over a smudge on a window. The thing is, when he praised you—and he did, sometimes—you’d work sixteen hours straight for more of it. I’ve never felt that vindicated since.” He stops turning the cup. “I left after he threw a pan near my station. Not at me. Near me. I went home that night and couldn’t actually stop shaking. They took me to hospital after six hours. My girlfriend said I should quit. I said I couldn’t, not mid-season, not when we were about to get the second star. She said she was leaving if I didn’t.” He picks up the coffee, finally drinks and holds his gaze steady. “I went back the next day and she was gone when I got home. I stayed another eight months before I finally walked out.” He works at a gastropub now, he says. Decent hours. Nobody throws anything. “Sometimes I look up what he’s doing. Check the reviews. I don’t know why. I shouldn’t care.”

Such workplace cultures do not grow spontaneously; they are cultivated and spread through deliberate schemas that mirror the dynamics of narcissistic family systems explored in Chapter . Just as narcissistic parents create roles of golden children and scapegoats (Chapter ), toxic workplaces develop hierarchies of favourites and targets. The tension is the gradient of manipulation. Just as children in such families learn to suppress authenticity for survival, employees in toxic cultures are forced to develop False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. professional personas. The workplace transforms into a retraumatisation site for those with histories of narcissistic abuse while serving as training grounds for those learning these dynamics for the first time.

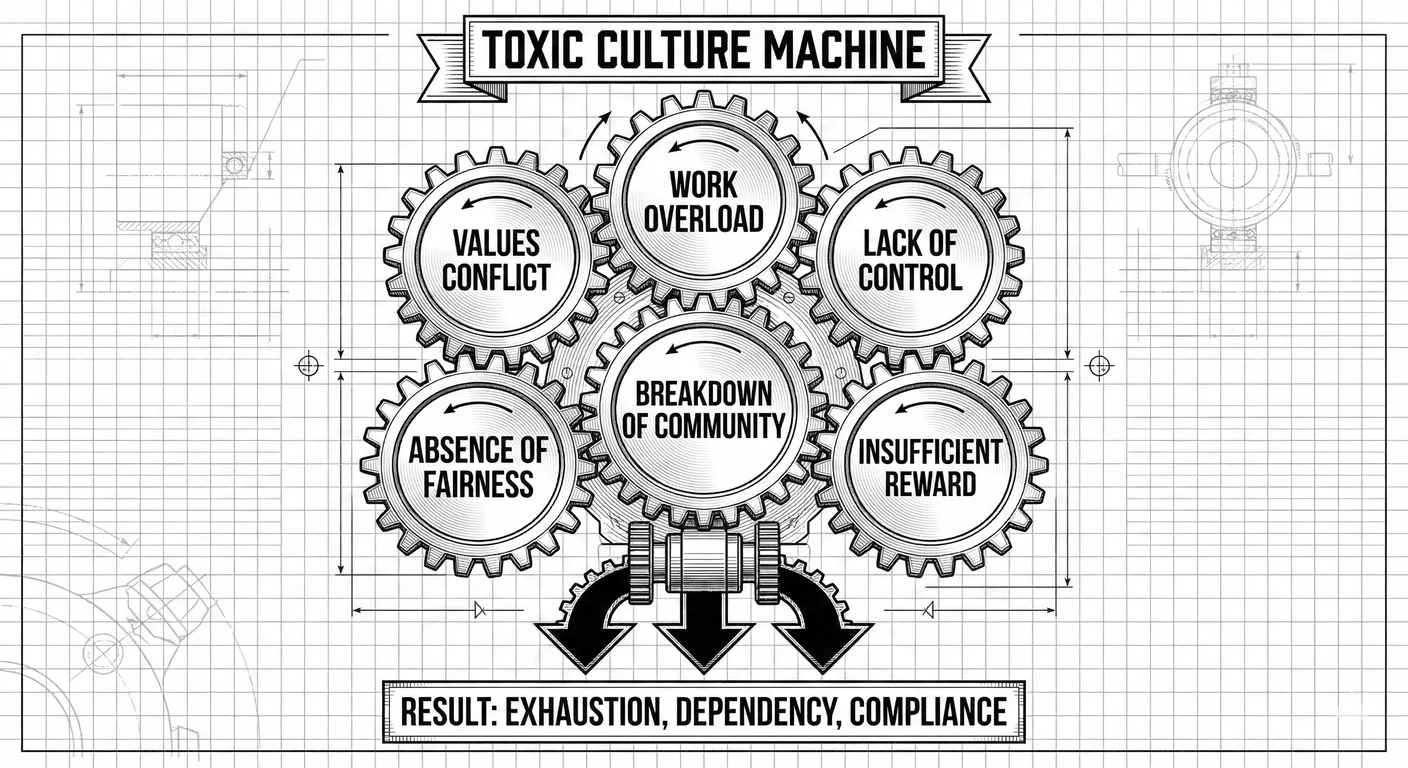

Dr Christina Maslach and Dr Michael Leiter 807 identify six factors that create workplace toxicity: there is work overload, and a lack of control, the reality of insufficient reward, isolation and breakdown of community, a palpable absence of fairness, and finally an engineered values conflict. While these can and sometimes do arise from poor management, in pathological organisations they are deliberately engineered rather than accidental mismatches between person and job environment. Those mismatches are usually spotted and fixed in healthy companies. Each of these factors serve the narcissist. Work overload keeps employees too exhausted to resist. Lack of control maintains dependence on leadership. Insufficient reward creates competition for scraps of recognition. Community breakdown prevents collective resistance. Absence of fairness normalises arbitrary treatment. Values conflict between stated and actual priorities forges the cognitive dissonance that characterises such environments. While non-clinicians cannot diagnose individual officers or staff with narcissism, these factors are each identifiable, and arise out of narcissistic traits in either leadership or the organisation itself.

The concept of “toxic culture” gained prominence through Dr Jeffrey Pfeffer’s 983 research on how workplaces literally kill people. He found that workplace stress is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States, contributing to 120,000 deaths annually and accounting for up to 8% of healthcare costs. Stress itself is a corporate rebranding of the term ‘unhappiness’ which occurred as unhappiness is usually directed. If you ask someone why they are unhappy they will point out they are overworked, or there are specific problems. This creates problems for the organisation and so the rebranding and reframing to ‘stress’ and ‘stress management’ with the implicit message that if an employee can’t cope with the stress through identified ‘stress management techniques’ they are ‘not a good fit for the role’ and so lose their job.

The pathological workplace, with its constant performance pressure, emotional manipulation, and empathy deficit, creates chronic stress that manifests directly in cardiovascular disease, immune dysfunction, and mental illness. The corporation’s lack of empathy for employee wellbeing mirrors the narcissistic parent’s inability to see children as separate beings deserving of care.

These dynamics appear across industries, not just in corporate towers. The hospitality industry, creative fields, and family businesses all show elevated rates of abusive supervision 132 . The common thread is not the industry but the power structure: wherever accountability is weak and prestige is high, these patterns flourish. Fashion runs on creative directors whose “vision” excuses cruelty. Architecture and academia—anywhere that prestige substitutes for fair compensation—enable an exploitative leader to trade on the privilege of association: you should be grateful to work here. The transaction is always the same: your dignity for their reflected glory.

The manipulation of “cultural gaslighting” operates throughout toxic organisations. Dr Stephanie Sarkis 1087 describes how toxic workplaces systematically and deliberately undermine employees’ reality perception. Performance standards shift without notice. Verbal agreements are denied. Success metrics change after goals are met. Promises of promotion evaporate. Documentation disappears. Employees begin doubting their perception and competence. This organisational Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. serves the same function as parental gaslighting by creating dependency through confusion and self-doubt.

Dr Amy Edmondson’s 351 concept of psychological safety is systematically destroyed in pathological company cultures. Teams with higher psychological safety demonstrate more learning behaviour and improved performance; for survivors of narcissistic families, toxic workplaces recreate childhood dynamics where speaking truth invites punishment. Employees learn that admitting error leads to scapegoating and asking questions reveals weakness, even raising minor concerns marks one as “not a team player.” The result is what Dr Elizabeth Morrison and Frances Milliken 893 call “organisational silence”, the collective suppression of information that might challenge leadership.

The proliferation of what David Graeber 482 colourfully called “bullshit jobs” shows us another dimension of workplace narcissism. Graeber identified five types of roles endemic to such environments: flunkies who exist to make someone look important, goons in aggressive but pointless roles, duct tapers who fix problems that should not exist, box tickers who allow the organisation to claim it is doing something it is not, and taskmasters who create or supervise unnecessary work.

Think of corporate lawyers designing tax avoidance schemes, or marketing consultants creating need for unnecessary products or ‘transformations’, a tier middle managers managing other middle managers—the pathological organisation creates these roles to build hierarchy rather than productivity. The layers of subordinates whose primary function is making superiors feel important, social theatre ensuring narcissistic supply and demonstrating for others how dependent the environment is on their leadership and vision. Employees in these jobs experience what Graeber calls “spiritual violence”, the soul-crushing recognition that one’s life energy is being consumed for nothing.

Susan Fowler’s memoir Whistleblower documents some of these dynamics at Uber 409 . On her first day as an engineer, her manager propositioned her via chat message. When she reported to HR, they said this was his “first offence” and no action would be taken—despite other women having reported the same manager. Over her time at Uber, she documented systemic patterns: women warned not to report harassment, performance reviews weaponised against complainers, “high performers” protected regardless of behaviour. Her 2017 blog post went viral, leading to investigations that culminated in CEO Travis Kalanick’s resignation. The personal cost was substantial: “Every day for years, even after I left, I expected something bad to happen.”

“Hustle culture” has normalised toxic workplace dynamics as aspirational 335 . The message is that suffering equals success and that exhaustion proves commitment and only sacrifice demonstrates ambition—these are the same dynamics narcissistic parents use to extract Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. from children, repackaged as professional development.

The Recursive Loop

The relationship between narcissistic systems and those within them is recursive. The narcissists build the system, and the system sculpts those who inhabit it to serve them. Gregory Bateson’s concept of “complementary schismogenesis” describes the diamorphic mechanism: in dominance-submission relationships, the behaviour of one party elicits a fitting but divergent response from the other. 85 The more dominant the leader becomes, the more submissive the subordinate must become to maintain the relationship—which in turn encourages the leader toward greater dominance. This loop explains why the gap between “Architect” (leadership with impunity) and “Instrument” (employees with accountability) grows over time. The system creates a runaway dynamic where the leader’s grandiosity requires an ever-expanding negative space of employee submission to sustain it. DiMaggio and Powell’s “institutional isomorphism” explains how these patterns colonise entire industries: organisations reshape themselves to fit the demands of powerful internal figures (coercive isomorphism) and the inertial obedience provided by traditions and prevailing prior norms, and when grandiose leadership is culturally coded as “visionary,” other organisations copy these structures (mimetic isomorphism). 313

Stanley Milgram’s research on obedience identified the “agentic state”—the psychological shift from viewing oneself as free actor to viewing oneself as instrument of another’s will. 862 While Milgram saw this as situational, narcissistic systems make it structural. The employee in a toxic organisation goes far beyond simply obeying orders; they internalise the leader’s pathology to the extent that they anticipate desires and suppress their own ethical agency before orders are even given. This “anticipatory obedience” characterises the Enabler in the narcissistic family and the loyal lieutenant in the pathological workplace. The result is what Balfour and Adams call “administrative evil”—ordinary people engaging in destructive acts because their agency has been submerged into their professional role. 70 The moral cauterisation required to work in a pathological bureaucracy mirrors the dissociation of the trauma victim: with a tunnelled focus on the efficiency of the process while avoiding responsibility for the ethical outcome.

The Entrepreneurial Paradox

Aisha, twenty-six, joined a fintech startup in London straight from university. We meet in a coffee shop in Shoreditch, not far from where the office used to be—before it closed. She still has the company hoodie on. “It’s comfortable,” she says when she notices me notice. “I should probably throw it out.” She shows me photos on her phone: an open-plan office with bean bags and ping-pong tables, team photos with everyone making heart signs with their hands. “I missed my grandmother’s last months. We were about to close the Series B. That’s what he kept saying. ‘Two more weeks.’ Then two more.” She scrolls to another photo: herself at a whiteboard, marker in hand, grinning. “I was good. I mean, I think I was good. It’s hard to tell now. He’d say things in one-on-ones that made you feel like you were the only person who really got it. Then you’d find out he said the same things to everyone.” The Series B never closed. “When it fell in, he gave a speech. Called us family. Then sixty people got the same email at 11pm. He was in Bali by then.” She locks her phone but doesn’t put it away. “My parents keep asking when I’m going to get a real job. I keep almost telling them about it. What I was doing, what it felt like. But I don’t know how to explain it without sounding like I was stupid. Maybe I was stupid.” She unlocks the phone again, scrolls to a photo of the founder at an all-hands. “He’s advising startups now. I saw it on LinkedIn. ‘Lessons in resilience.’ Four hundred likes.”

The concept of “unicorn” companies—startups valued at over $1 billion—has created perverse incentives that reward grandiose excess over sustainable business building. Dr Martin Kenney and John Zysman 646 describe how the unicorn economy prioritises growth over profitability and valuation over value creation. Companies lose billions annually while being valued at tens of billions. This disconnect from economic reality requires the kind of reality distortion that narcissists excel at, convincing themselves and investors that normal rules do not apply.

Dr Melissa Williams and colleagues 846 found that grandiose entrepreneurs create what they call “contagious visions”—grandiose narratives that spread through organisations and investor networks like social contagions. Employees join what are essentially cults of personality rather than companies. They accept lower wages for equity in the founder’s vision. They work crushing hours to be part of something “revolutionary.” They internalise the founder’s grandiosity, seeing themselves as changing the world rather than building a business. When reality inevitably intrudes, the psychological crash affects not just the grandiose founder but everyone who bought into their distorted reality.

Commercial Cult Dynamics

Josh, twenty-two, was what he calls a “reply guy” for a tech entrepreneur—not Musk, he is quick to clarify, but “someone in that orbit.” We meet at a gaming café in Bristol. He orders a Coke and doesn’t touch it. “I was fifteen when I started. He was doing interesting stuff with rockets or whatever. I’d argue with people online for hours. My dad kept telling me to go outside. I thought he didn’t understand.” He picks at the label on the Coke bottle. “I knew everything about this guy. His backstory, his companies, his feuds. I could explain why every criticism was wrong. I had folders. Screenshots. Saved articles.” He finally takes a sip. “There was this woman who worked for one of his companies. She tweeted something about working conditions. Not even that critical. And people—people I’d been arguing alongside for years—started threatening her. Her address got posted somewhere.” He puts the bottle down. “I didn’t post her address. I didn’t send threats. But I’d spent years building up the community that did. I’d spent years saying anyone who criticised him was jealous or stupid or didn’t understand. I made it okay.” He looks at the bottle. “I deactivated everything. My mum asked why I seemed happier. I didn’t know how to explain that I’d spent six years of my life on something I couldn’t even describe without sounding insane. I told her I was just tired of social media.” He still checks the entrepreneur’s account sometimes, he admits. On a burner. Just to see what’s happening. He doesn’t engage. “It’s like looking up an ex. You know you shouldn’t.”

The cult dynamic extends beyond employees to consumers. When commercial figures cultivate devoted followings who attack critics, defend controversies, and provide constant validation, we observe something beyond brand loyalty: a self-reinforcing system where the figurehead and the collective reinforce each other. The figure provides identity and meaning to followers; followers provide supply and protection to the figure.

A note on the distinction that follows: The case studies in this section examine parasocial system dynamics, and not personal conduct. The figures discussed below represent a phenomenon where legitimate achievement and system cultivation may become inextricable, and where the analysis concerns structural patterns rather than individual wrongdoing.

Elon Musk and Taylor Swift warrant examination not as cautionary tales but as case studies in how genuine achievement becomes inseparable from system cultivation. Both are historical figures whose industry impact is substantial: Musk’s companies accelerated electric vehicle adoption and reduced space launch costs 1268 ; Swift’s Eras Tour generated an estimated $5.7 billion in U.S. consumer spending 1018 . These achievements are measurable and lasting.

Both the business mogul and the popstar icon successfully invested in cultivating specific parasocial systems inseparable from their commercial success. Dr Gayle Stever’s 1186 research documents how followers developed one-sided emotional bonds with public figures, experiencing criticism towards their chosen icons as personal attack. Both types of parasocial systems developed sophisticated mechanisms for activating these bonds.

Musk’s career trajectory illustrates the progression. His early persona emphasised engineering 1268 . By the mid-2010s, his social media presence had become central to Tesla’s brand, with researchers finding his Twitter activity directly affected stock price 32 . His 2022 acquisition of Twitter (now X) represented a natural milestone: owning the platform through which global parasocial relationships are historically deployed. When journalists investigated his companies, followers flooded them with harassment. When regulators questioned claims, they were framed as enemies of progress. The pattern was consistent: the parasocial system of followers could not tolerate external reality that contradicted its image of their icon.

What makes this dynamic significant is its commercial nature. Unlike political cults these movements explicitly serve profit. Tesla’s market capitalisation—at times exceeding the next ten automakers combined despite producing only a fraction of their vehicles—depends at least partly on the public belief in Musk personally 32 . The parasocial relationship is the product. Critics who distinguish between “the cars” and “the tweets” missed the point: in commercial cult dynamics, the controversy is the marketing.

Swift’s career evolution shows similar progression. Her early career positioned her as relatable; by the 2010s, she had developed what scholars describe as “calculated authenticity” 253 . Her “Swifties” operate with military precision: they ran coordinated streaming campaigns with mass reporting of critical content, and documented harassment of unflattering journalists. The re-recording of her early albums functioned as a loyalty test and engagement driver. Fans were enlisted as soldiers in a commercial dispute reframed as moral crusade 81 . Both Musk and Swift have parasocial systems which present them as outsiders despite being institutional and among the most commercially successful figures in the histories of their industries. This is a structural positioning that pre-empts criticism, and flatters followers, deliberately creating an in-group cohesion. Dr Robert Lifton’s 742 criteria for thought reform include precisely this dynamic.

The key insight is that the figurehead is not the point. Neither Musk nor Swift matter. They could retire tomorrow and the fandom’s organisational structure would persist, seeking new objects. When they do step down their community would reframe their absence as persecution or martyrdom. This is a system—one where replaceable figure and replaceable following have become mutually constitutive.

The progression from achievement to system cultivation to dependency appears to distinguish commercial cult dynamics from ordinary celebrity. Many artists sell records; few are able or willing to build armies. The pattern suggests that at certain scale, maintaining market dominance requires cultivating a free labour pool of exploited individuals who are attached enough that they will attack anyone who questions the value of the brand identity. Commercial cult dynamics represent the commodification of the earlier narcissistic family structure: the brand figure’s icon assumes the parental role (inconsistent, demanding loyalty); followers then assume the dependant role (seeking validation, defending against criticism). The relationship is no longer about the product or service but about exploitation and value extraction through a rented feeling of belonging. We can term this pattern Identity Renting.

The durability of these parasocial systems distinguishes them structurally from traditional fraud-based enterprises. When corporate leaders are convicted the value proposition is usually the deception itself. The commercial cult dynamic operates differently: an iconic business mogul’s controversies are there to intensify their following, each criticism confirming the persecution of genius narrative. The system is not fragile like fraud; it is resilient with characteristics like an ideology. This is not to equate controversial behaviour with criminal conduct, but we can observe that the parasocial system itself is a more evolved expression of the corporate narcissus—one that regenerates rather than collapses. This is because it can rest on genuine achievement subsequently wrapped in identity cultivation rather than on fabricated claims.

Case Studies in Corporate Narcissism

The Unicorn Graveyard

The term “unicorn” itself tells a story worth examining. Venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined it in 2013 to describe startups valued at over $1 billion 717 , mythical creatures, she meant to emphasise, because such valuations were statistically improbable. Only 0.07% of venture-backed companies achieved unicorn status. The term was meant as a caution: do not expect to find one, do not bet your career on catching one, do not mistake the rare exception for the achievable norm.

Instead, unicorn became an aspiration. At the height of the unicorn boom, over 1,300 existed globally 223 . The impossible had become the expected. Founders who once might have built sustainable businesses now chased billion-dollar valuations. Employees who once might have sought stable careers now accepted below-market salaries for equity that would be worth fortunes, when, not if, the unicorn emerged. Investors who once might have demanded profitability now funded companies losing hundreds of millions annually, betting on growth that would eventually, somehow, turn into returns.

The unicorn hunt created ideal conditions for corporate psychopaths 132 : an ecosystem where confidence mattered more than competence, where questioning the vision meant lacking vision, where the bold projections of charismatic founders were rewarded over the cautious assessments of experienced operators. The desperation to “get in”, to join the next Google, to catch the next Facebook, to not miss the next Amazon, created “suspended disbelief at scale.” Normal due diligence felt like a betrayal of the entrepreneurial spirit. Scepticism transformed into a character flaw. Belief was the price of admission.

The graveyard extends far beyond historical examples such as Theranos or FTX. The pattern is depressingly consistent: supreme confidence, dismissal of sceptics, burn rate that would terrify anyone without access to seemingly unlimited funds, and then, suddenly, nothing. The question arises why did the system keep funding them?

Travis Kalanick’s trajectory after Uber is instructive. His departure from the company he founded followed extensive reporting on Uber’s culture, documented through internal documents and extensive interviews. 593 The company’s aggressive expansion and internal dysfunction contributed to his exit. Months later, he raised $400 million for CloudKitchens, a “ghost kitchen” venture promising to disrupt the restaurant industry 353 . The playbook looked familiar: move fast, expand aggressively, worry about consequences later. Perhaps he’d learned from his experiences. Or the system simply does not require learning—it funds the next venture which matches the pattern for attention regardless.

Counting the Cost

Sana, thirty-eight, was a senior project manager at a Big Four consulting firm. Her departure was part of the Great Resignation, though she did not know that is what it was called until later.

“I didn’t quit because of the return to office. That’s what I tell people, because it’s easier. The real reason is harder to explain.” She picks at a thread on her sleeve. “During lockdown, I was home for the first time in years. Actually home. I’d make breakfast for my kids. I’d see them at lunch. I was still working sixty hours, but I was there. My daughter started telling me things. School things, friend things. She’d never done that before. I realised she’d stopped trying years ago because I was never available.”

She looks out the window. “When they announced return to office, I calculated the commute. Three hours a day. That was fifteen hours a week I’d lose. I kept thinking about my daughter’s face when I told her I’d be gone again.”

She did not quit that week. She went back for three months.

“I kept thinking I could make it work. Leave earlier, come home later. Maybe work on the train. Everyone else was doing it.”

She finally left when her daughter stopped telling her things again. “I run a small practice now. Three clients. I make less. My old colleagues think I gave up. Maybe I did.”

She turns back from the window. “My daughter’s thirteen now. She talks to me sometimes. Not always. I don’t know if I left too late or just in time. I don’t know if it mattered.”

Human Costs

The human toll of corporate narcissism extends beyond economic losses to serious psychological and physical damage that ripples through families and communities. Dr Jeffrey Pfeffer’s 983 research found that workplace stress contributes to an estimated 120,000 excess deaths annually in the United States alone—more than kidney disease or suicide. While Pfeffer’s research addresses workplace stress broadly (including long hours, lack of autonomy, and job insecurity), toxic leadership is one significant contributor to these conditions. The patterns documented here—chronic pressure, emotional manipulation, empathy deficits—create precisely the conditions Pfeffer identifies as lethal.

Suicide rates in corporate settings with problematic leadership reveal the ultimate human cost. France Télécom (now Orange) experienced 35 employee suicides between 2008-2009 during a restructuring led by CEO Didier Lombard, who was later convicted of “moral harassment” by a French court in 2019. Trial evidence indicated management created pressure to force departures. Foxconn, Apple’s primary manufacturer, installed suicide nets after a reported 18 workers died by suicide. Amazon warehouse workers have reportedly attempted suicide on the job, according to media investigations. These are not isolated tragedies but consequences of environments that deny human dignity and worth.

The mental health epidemic in corporate settings mirrors the trauma patterns seen in narcissistic families. Dr Christina Maslach 806 found that employees under such leaders experience symptoms identical to those of abuse victims: emotional numbing and identity disturbance. The workplace retraumatises and deepens the scars of those with histories of narcissistic abuse and causes initial traumatisation for those encountering it for the first time.

Family destruction follows employees home from pathologically-led organisations. Dr Dawn Carlson 202 found that abusive supervision predicts marital conflict, parenting problems, and even domestic violence. Pressure and misery radiate out into family. The employee who spends all day managing an exploitative boss’s emotions has no emotional resources left for family. Children grow up with parents who are physically present but psychologically absent, thereby perpetuating cycles of emotional neglect explored in earlier chapters’ discussion of developmental causes.

Physical health consequences compound psychological damage. Dr Joel Goh 461 found that employees in high-stress, pathologically-led organisations have 50% higher healthcare costs. This come from cardiovascular disease, stress related immune dysfunction, and metabolic disorders with the body manifesting what the mind endures. The narcissistic leader who denies bathroom breaks to warehouse workers, and who demands 80-hour weeks from developers, and cultivates cultures of fear and competition literally shortens human lives. This is violence enacted through intentional corporate policy rather than overt physical force.

The Pandemic Revelation: Mass Escape and Narcissistic Recapture

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unintentional experiment: what happens when millions of employees escape direct pathological oversight? The results were revelatory. Between April and September 2021, more than 24 million American employees quit their jobs—an all-time record. By year’s end, 47 million had resigned in what became known as the Great Resignation 1198 .

MIT Sloan Management Review’s study identified the cause: “A toxic corporate culture is by far the strongest predictor of industry-adjusted attrition and is ten times more important than compensation in predicting turnover.” Not twice as important. Not three times. *Ten times. *The leading elements contributing to toxic cultures—failure to promote diversity, workers feeling disrespected, and unethical behaviour—map directly to pathological leadership patterns: the exploitation of designated groups, the empathy deficit that makes respect impossible, and the grandiosity that places the leader above ethical constraint.

GoodHire’s survey confirmed: 82% of employees would consider quitting because of a bad manager. Nearly one-third of workers who quit during the Great Resignation did so specifically to escape pathological company culture characterised by discrimination, harassment, verbal abuse, and poor work-life boundaries 475 . The pandemic did not create this misery; it revealed its scope. Workers discovered their suffering was not inherent to work—it was inherent to their workplaces. Remote work offered escape from the toxic leader’s constant presence, the daily humiliations, the performance of deference. Many felt the benefit of escape and chose never to return.

What followed was revealing: demands by controlling leaders for return to office. Within two years, 30% of S&P 500 companies had imposed return-to-office mandates. A University of Pittsburgh study analysing 137 firms found these mandates produced no improvement in financial performance while 99% saw drops in employee satisfaction and 42% experienced higher than normal attrition 314 . By the study’s measures, the mandates failed to deliver promised benefits.

The study’s most significant finding, however, concerned who imposed these mandates: “Companies led by ‘power-seeking CEOs’—typically males who command notably higher salaries compared to the next highest-paid executive—were more likely to enforce top-down RTO mandates. This finding strongly suggests that RTO mandates often stem from a desire for performative grandiose dominance rather than from thoughtful strategies aimed at improving firm performance.”

The pattern invites analysis through an NPD lens. Ignoring productivity data that contradicts the leader’s preference suggests grandiosity. Demanding physical presence regardless of demonstrated remote effectiveness suggests control. Punishing workers who request flexibility suggests difficulty tolerating autonomous behaviour. Justifying mandates with vague “culture” rhetoric while evidence shows satisfaction declining suggests disconnect between stated and actual motivations. For leaders who experienced remote work as loss of direct observation—the ability to see subordinates, to interrupt their focus, to remind them who holds power—the demand may have been less about productivity than about presence itself.

Psychology Today’s analysis was blunt: “Remote work represents a loss of direct observation over employees and their working hours. For leaders accustomed to micromanaging, remote work poses a threat to traditional command-and-control management styles.” The threat was not to business outcomes but to the grandiose leader’s sense of being seen as dominant.

The ongoing exodus represents a mass boundary-setting event unprecedented in employment history. Millions of workers were simultaneously refusing exploitative demands for the first time in their careers. Those with options started leaving toxic environments entirely. Those without options were “quiet quitting”—withdrawing the discretionary effort that narcissistic systems have long extracted through fear and manipulation without pay. Either way, the narcissistic corporation discovered limits to how much it could take from workers who now understood they have choices.

The pandemic revealed what this book has traced through families, relationships, and institutions: narcissistic systems depend on the compliance of those they exploit. When that compliance is withdrawn, whether by adult children going no-contact with narcissistic parents, partners leaving narcissistic relationships, or workers refusing to return to toxic workplaces, the system’s power collapses. The Great Resignation and ongoing resistance to return-to-office mandates represent this book’s thesis writ large across the economy: recognition of narcissistic patterns is the first step towards refusing to participate in them. Despite what they may say, the world continues to turn.

Conclusion: The Narcissistic Corporation as Mirror and Multiplier

| Micro (Individual) | Meso (Organisation) | Macro (Society) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Unit | Child-Parent Dyad | Employee-Leader | Citizen-State |

| Mechanism | Serve-and-Return Failure | Institutional Isomorphism | Malignant Normality |

| Agency Alteration | Neural Pruning / False Self | Agentic State / Role Absorption | Vicarious Narcissism |

| Relational Dynamic | Complementary Schismogenesis | Folie à Deux | Theft Conversion |

| Outcome | The Hollowed Self | Administrative Evil | Authoritarian Submission |

| The Fractal Hierarchy of Narcissistic Systems. The same patterns of agency alteration, relational dynamics, and outcomes appear at individual, organisational, and societal scales—suggesting structural isomorphism rather than mere analogy. |

The pathological corporation reflects deeper cultural values rather than representing an aberration. Contemporary economic systems reward traits that erode human community: grandiosity over humility, extraction over creation, appearance over substance, individual achievement over collective wellbeing. The pathological leader succeeds not despite their dysfunction but because of it, finding in corporate structures a vehicle for destructive patterns.

The corporation, as currently conceived, functions as a multiplier of narcissistic damage. The narcissistic parent harms dozens; the narcissistic CEO harms thousands or millions. The family scapegoat suffers alone; the corporate scapegoat’s destruction is public spectacle. The narcissistic family’s dysfunction remains private; the pathological corporation’s toxicity spreads through entire economies. Organisational structures amplify these patterns to previously unimaginable scale.

Just as a body is more than a collection of cells, the narcissistic corporation is more than a collection of difficult individuals. It is a living entity that has made the diamorphic choice at scale—choosing defensive grandiosity over authentic development. Like the individual narcissist, it builds a fortress to protect a void. 1329 Like the narcissist builds elaborate defences against recognising their own inadequacy, the narcissistic corporation constructs cultures, policies, and reward systems that insulate it from reality. The question of whether the false self can be dismantled and authentic development resumed—applies equally to organisations. The answer, at organisational scale as at individual scale, depends on whether the system can tolerate the vulnerability and accountability that genuine change requires.

The visibility of corporate narcissism—with its spectacular failures, the perennial documented frauds, and most importantly the measured human costs—creates conditions for change. Employees increasingly recognise pathological cultures and resist them. Investors have begun to learn how to identify pathological leaders and avoid them. Regulators, however captured, face increasing pressure to act. The very visibility which enables the attention economy also shines a light on failures and publishes them. The pandemic revealed the essential fragility of pathological societal constructions, as companies built on hype collapsed while those providing genuine value survived.

Alternative models not only exist; they thrive. There are as many forms of productive co-operation and healthy competition. Recent growth in cooperative businesses, benefit corporations, and stakeholder governance based systems demonstrate that other structures are effective. Companies like Patagonia, King Arthur Flour, and Mondragon Corporation show that businesses can succeed without requiring grandiose leadership. These are not perfect organisations but they demonstrate that the pathological corporation is a choice, not an inevitability.

The examination of political narcissism in the next chapter builds on this corporate analysis. The same individuals move between corporate and government power seeking shortcuts to supply at the cost of others. The same traits that generate pathological workplaces generate pathological politics across the spectrum . Corporate and political narcissism also reinforce each other, creating interlocking systems with concentrated benefits and dispersed costs. These are fertile ground for study in an interconnected digital future. The question of whether narcissism can be sufficiently constrained to preserve human dignity, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability remains open. The answer will shape our economic and political futures.