Introduction

In 2017, a group of psychiatrists did something their profession had avoided for decades: they publicly discussed a sitting United States president’s mental health. The collection of essays, “The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump,” edited by Bandy Lee 718 , featured 27 mental health professionals who argued that their “duty to warn” the public outweighed the Goldwater Rule’s prohibition against diagnosing public figures without examination. The rule had been established by the American Psychiatric Association in 1973, after a magazine poll invited damaging assessments of presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. The volume sold over 100,000 copies. It was translated into multiple languages. And it sparked a debate that continues to this day: what happens when the patterns clinicians recognise in their consulting rooms appear on the world stage?

Dr Robert Jay Lifton, one of the volume’s contributors, had spent his career studying this question. His research on Nazi doctors had examined how healers became killers 743 . His work on Chinese thought reform had mapped how totalist systems reshape individual psychology 742 . Now, at ninety, he saw patterns he recognised. “Malignant normality,” he called it, the process by which a society comes to accept as normal what would previously have been seen as dangerous pathology 744 .

Lifton’s concept provides the framework for understanding what happens when the narcissistic traits we’ve seen earlier such as grandiosity and empathy deficits manifest in those who hold political power. The clinical literature is remarkably extensive. Jerrold Post, who founded the CIA’s Centre for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behaviour spent decades studying leaders from Saddam Hussein to Kim Jong-il 1003 . His research identified consistent patterns in what he termed “narcissistic leadership”—patterns that surprisingly transcend culture and political systems.

Post’s work, like Lifton’s, was grounded in careful observation rather than polemical assertion. When he described the “mirror-hungry” personality’s need for constant affirmation he cited clinical literature and case studies. In analysing narcissistic leaders and their followers, he drew on decades of intelligence assessments and psychological profiles. This approach of observation first, theory second, guides us here.

The historical record offers abundant material as far back and even beyond Plutarch’s lives of Alcibiades and Nero. Ian Kershaw’s meticulous biography of Hitler 656 is another touchstone, as is Robert Service’s studies of Stalin 1118 . Li Zhisui’s intimate memoir of Mao 739 provides valuable insight into the fundamental universality and damage of these traits even in very different cultures. These sources reveal recurring patterns across centuries and societies, because narcissistic behaviour leaves distinctive marks regardless of whether historians search for them. The grandiose building projects. The purges of former allies. The reality-distorting propaganda. The rages that terrified subordinates. The inability to acknowledge error even when catastrophe loomed. These are familiar and perennial refrains.

Watts and colleagues 1305 provide a good starting point, having rated U.S. presidents on grandiose narcissism using expert assessments, and finding significant variation, and significant correlations with both leadership effectiveness and ethical failures. Deluga 302 found that charismatic leadership and narcissism overlapped substantially. Do the traits that help leaders rise also make them dangerous once in power? These studies identify patterns worth understanding, leaving aside questions of individual diagnosis.

One thing which helps our understanding is that Democracy makes specific psychological demands. It requires accepting that one might lose, and in turn that opponents have legitimate standing. This means accepting that power must eventually be surrendered. These realities create particular tensions with NPD.

The connection between individual and political narcissism is profoundly structural. We’ve seen how narcissism can be “isomorphic across levels”—the same patterns appearing with equivalent meaning at individual, group, and societal scales. 671 Agnieszka Golec de Zavala’s research programme on “collective narcissism” also provides direct empirical evidence: when items from individual narcissism measures are translated to the group level, they predict the same dynamics—inflated group-image, entitlement, hostility when recognition is denied. 464 This applies visibly and dramatically to political groups. Nations, like individuals and companies, can construct false public images: grandiose narratives of exceptional destiny that insulate them from recognising their actual condition or accepting accountability for their history. The political narcissist exploits this mercilessly, offering followers participation in a collective grandiosity as compensation for their individual insignificance in relation to their leaders.

A nation confronting historical trauma—such military defeat, economic collapse in the form of stock market crash, loss of empire, demographic displacement—can integrate the experience, grieve what was lost, and construct identity around present reality and future possibility (authentic development). This path has been taken by various nations like Germany or Japan to various degrees of success. Or a nation can construct a collective false self: grandiose narratives of stolen greatness, designated enemies responsible for every wound, and a political culture organised around restoring what was never quite as it is remembered (defensive rigidity). Germany after 1945 eventually chose the first path—painful reckoning with historical crime, identity rebuilt around democratic values and European integration. Germany after 1918 chose the second—Versailles as injury, Jews and immigrants as designated enemies with Hitler as a grandiose figure who would restore what had been ‘stolen’.

The developmental trajectory at national scale mirrors the individual pattern we saw: unmetabolised trauma produces defensive reaction, and a hardening of the collective psyche; the defensive adaptation becomes entrenched as a series of knee-jerk responses and tropes that inform political culture. That same entrenched culture produces the characteristic narcissistic patterns at scale including reality distortion, enemy designation, exploitation of followers as supply for the leader’s grandiosity. What authentic national development looks like is visible in societies that can acknowledge historical wrongs. They not only tolerate internal dissent, they welcome it as a way to move to a better more stable way of living. They treat minority populations as full citizens rather than in name only and not as scapegoats, and these nations therefor derive a stable and strong collective identity from present contribution rather than any mythologised past. Such societies exist; they are simply less dramatic than their narcissistic counterparts. This makes them less visible in news cycles that reward conflict over stability.

Narcissistic abuse as theft—at any level it involves theft of certainty and power, and ultimately theft of the shared relationship itself. The narcissistic parent steals the child’s reality through Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. . The narcissistic partner steals autonomy through Coercive Control Coercive Control A pattern of controlling behaviour that seeks to take away a person's liberty and autonomy through intimidation, isolation, degradation, and monitoring. . The narcissistic colleague steals credit and professional identity. In each case, what should be reciprocal becomes extraction: the narcissist takes what they need while demanding ever-increasing costs. They do not reciprocate to balance the relationship.

Political systems led by figures displaying these traits operate identically, merely at scale. They convert shared institutions into instruments of personal aggrandisement. The shock that citizens report, of the sense that something essential has been violated, is the same shock survivors of narcissistic families describe. They are stunned by the discovery that what appeared to be mutual was actually parasitic. The relationship was not shared; it was being consumed.

The patterns feel so familiar regardless of ideology because the structure remains constant even as content differs. Left or right, secular or religious, nationalist or revolutionary—the cruelty, lies, exploitation, and hurt persists. The narcissistic system demands a new “cost” for citizenship, just as the narcissistic parent demands supply and obedience as the price of remaining in the family. The degradation of norms mirrors the erosion of boundaries in narcissistic families. The Trauma Bonding Trauma Bonding A powerful emotional attachment formed between an abuse victim and their abuser through cycles of intermittent abuse and positive reinforcement. that keeps followers attached despite harm operates through the same neurological pathways as attachment hijacking. The Triangulation Triangulation A manipulation tactic where a third party is introduced into a relationship dynamic to create jealousy, competition, or to validate the narcissist's position. that sets citizen against citizen replicates the divide-and-conquer tactics of the narcissistic household. What society experiences as political crisis, survivors of narcissistic abuse recognise immediately as intimate violence made public.

The Strongman Appeal

In 1941, as fascism swept Europe, the German-American psychoanalyst Erich Fromm published “Escape from Freedom” 425 . His question was simple: why would people who had won political freedom voluntarily surrender it to effective dictators? His answer was psychological rather than political. Modern freedom, Fromm argued, creates burdens—prime among them the responsibility and the weight of endless choice, which many find simply unbearable. The authoritarian leader offers relief from these burdens. Surrender your autonomy, merge with something larger than yourself, and the anxiety dissolves.

Fromm called this “ authoritarian submission ”—an active pursuit of social submission as psychological relief, quite distinct from coerced obedience and from healthy assertive relationships with authority. The key difference is that the follower seeks to dissolve into the leader’s identity; by contrast, healthy relationships preserve autonomy and seek alignment through harmonisation and compromise. His insight has been confirmed repeatedly in subsequent research. Altemeyer’s decades of work on authoritarianism 24 found that high scorers on his Authoritarianism scale, designed for measuring submission to authorities and aggression towards outgroups, were disproportionately drawn to ‘strong leaders’ who promised ‘simple certainties’.

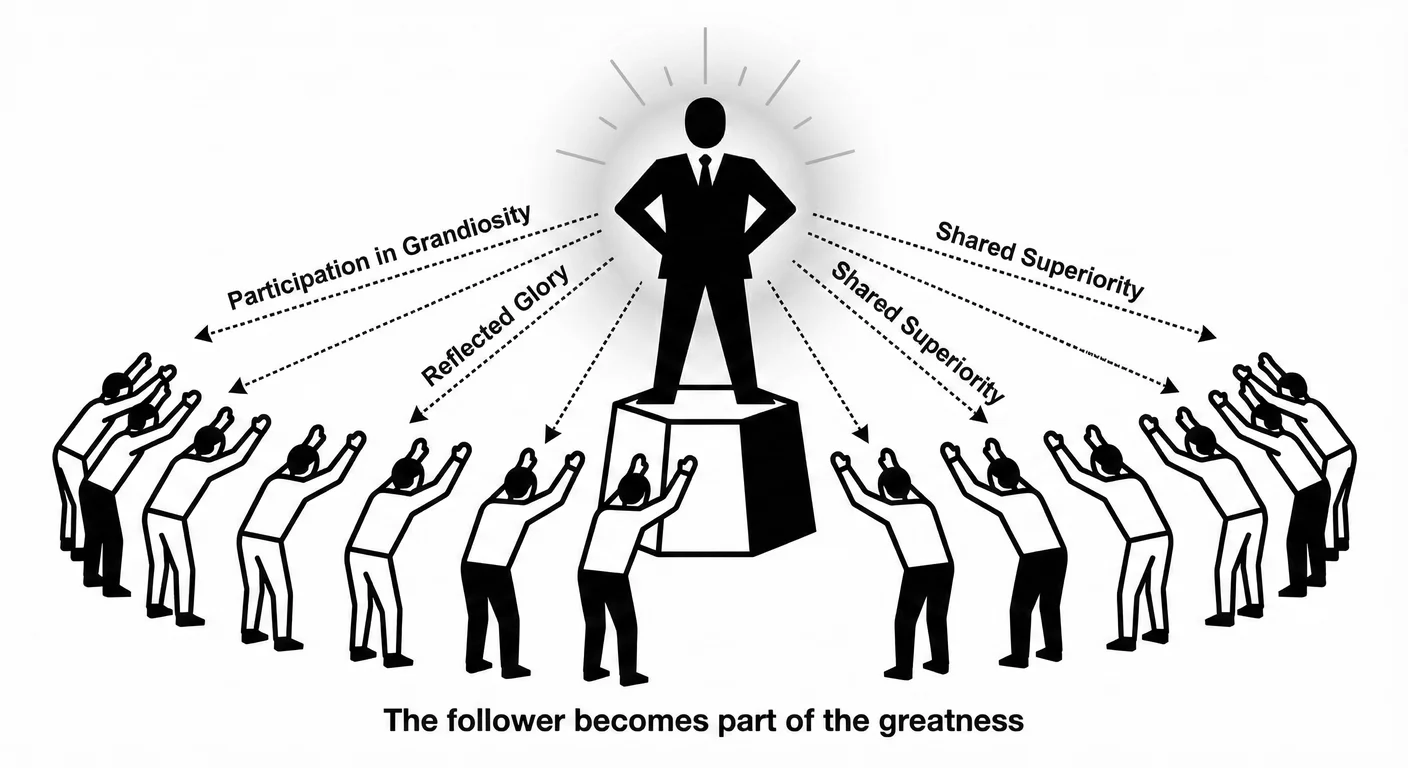

Why do these leaders generate such intense devotion? Plenty of authoritarian politicians offer certainty and order. Only some inspire the near-worshipful attachment that characterises ‘strongman’ movements. The difference, Post 1003 argues lies in what the leader offers beyond submission: a participation in grandiosity.

Post’s research on charismatic leadership identified what he called the “mirror-hungry” leader. One whose need for admiration establishes a particular dependency relationship with followers. Such leaders invite identification with their projected image and so going beyond mere demands for obedience. Followers share in the leader’s claimed superiority and so are doing more than merely submitting to his authority. Either hat represents participation in a movement’s grandiose self-image, beyond mere expression of political preference. The leftist Beret, or the MAGA hat mean the same thing. A movement’s slogan promises that “we” will make America great, or “we are revolutionaries” mean the follower becomes part of the greatness. Suddenly they are part of a movement, and it must be historic for their own lives to have significance. That significance is compensation for all the times they’ve been ignored or betrayed up until that point. And it is important to remember this is independent of whether they are on the left, or right, secular or religious. The pattern is identical, with identical impacts on their personal agency.

Stein 1174 described this as “vicarious narcissism”: the experience of narcissistic gratification through identification with a grandiose other. The phenomenon is well documented in clinical literature. Children of narcissistic parents often describe moments of reflected glory when the parent succeeded, feeling special by association. Cult members report similar dynamics, their self-esteem rising and falling with the leader’s fortunes. The strongman’s political movement operates on the same principle, just scaled up.

This helps explain findings that initially puzzled researchers. Hochschild 557 , studying Tea Party supporters in Louisiana, found that economic self-interest predicted their political preferences poorly. Many supported policies that would harm them materially. What predicted their views was a sense of displacement, feeling like “strangers in their own land,” watching others “cut in line” ahead of them. The injury was to status, not income. The appeal of leaders who promised to restore their rightful place made psychological sense even when it made economic nonsense. The precise same injury and pattern is reported by those in socialist nations who felt that foreign colonial investors were extracting the wealth from their nations and they didn’t recognize their country due to strangers cutting in line, and having precedence.

Mutz 901 confirmed this pattern with experimental data. In her study, perceived threats to group status (particularly among those who felt their group’s dominance declining) predicted authoritarian support more strongly than personal economic concerns. The strongman’s promise to restore “greatness” resonated with those experiencing what might be called collective narcissistic injury—the exposed wound of mythic lost supremacy.

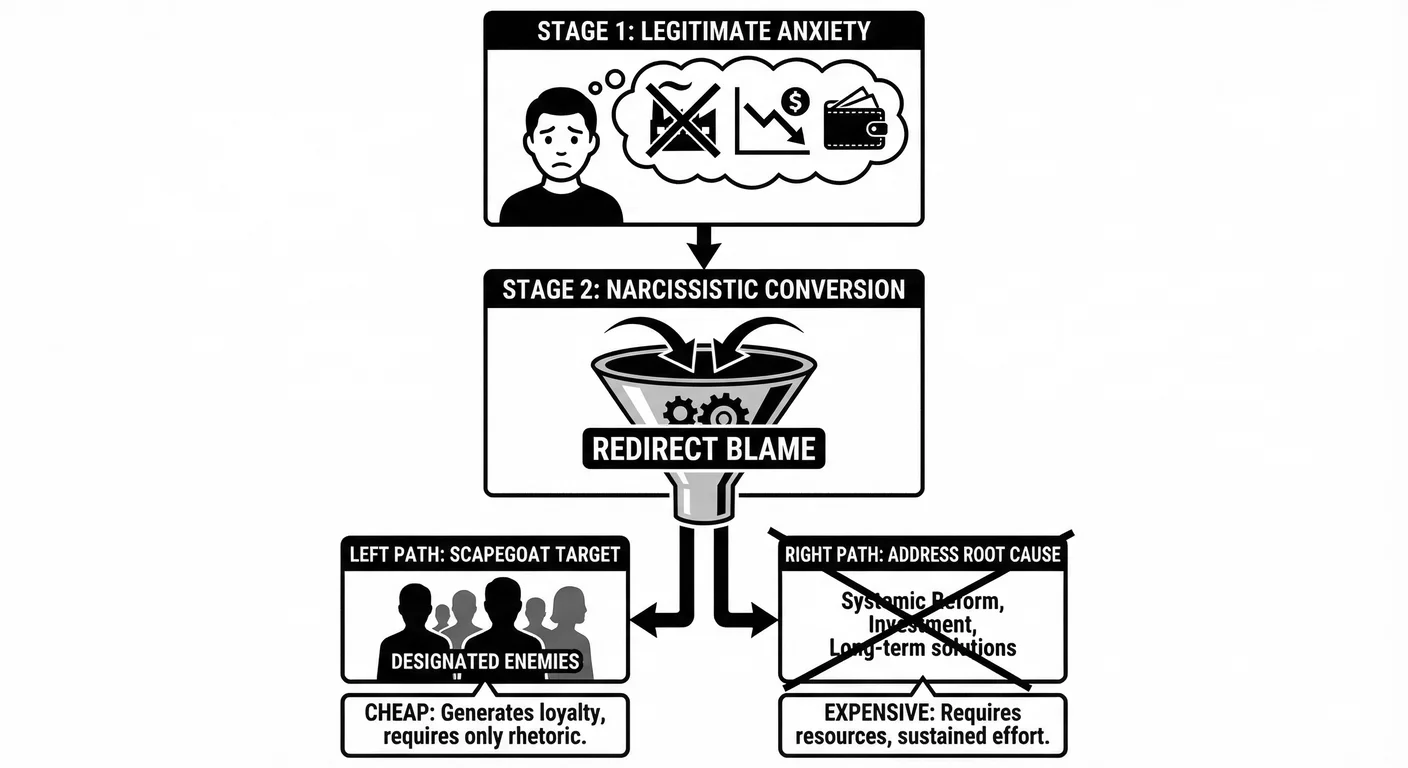

Here we encounter a pattern central to political narcissism, which we can term theft conversion. The narcissistic leader takes genuine anxieties—economic displacement and identity threat that feel like theft of one’s rightful place—and redirects them toward designated targets. “They” are taking your jobs. “They” are polluting your culture. “They” are replacing you. This redirection serves what we might call the narcissistic system’s economy: hatred is cheaper to produce than solutions. Providing actual economic security or material improvement to struggling communities would require resources and sustained effort. Manufacturing enemies requires only rhetoric. And hatred, once ignited, burns longer than satisfaction. A problem solved is a problem that no longer motivates; an enemy designated remains useful indefinitely. (The term “theft conversion” is offered as descriptive shorthand, not as established psychological construct; it parallels what political scientists call “scapegoating” and what clinical literature describes as “externalisation of blame,” but emphasises the economic logic of the exchange.)

This is Triangulation Triangulation A manipulation tactic where a third party is introduced into a relationship dynamic to create jealousy, competition, or to validate the narcissist's position. at national scale—the same mechanism narcissistic parents use when setting siblings against each other to maintain control. The narcissistic leader positions followers and designated enemies in perpetual conflict, extracting loyalty and free labour from followers who believe they are fighting for their survival. The leader offers symbolic gestures and partial fixes—a wall announcement here, a travel ban there—sufficient to maintain the appearance of action without resolving the underlying anxieties. Resolution would end the usefulness of the wound. The narcissistic system requires the injury to remain fresh, the enemy to remain threatening, the follower to remain dependent on the leader’s protection.

This is also Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. at national scale. The communities recruited into these movements often face genuine problems—deindustrialisation and declining life expectancy, eroding social infrastructure—but the narcissistic leader redirects attention from systemic causes towards scapegoats who had no role in creating the problems. Immigrants did not close the factory; trade policy did. African Americans did not create the opioid crisis; pharmaceutical companies did. The working-class communities most damaged by narcissistic economics become the most fervent supporters of narcissistic politics, their legitimate grievances converted into fuel for a system that will never properly address them. They are being gaslit about the source of their pain, and the gaslighting keeps them loyal because the alternative—recognising that their champion profits from their suffering—is psychologically unbearable.

The recognition that these mechanisms operate at political scale suggests something more troubling: narcissistic patterns are no longer just individual tactics but institutional architecture. The modern political campaign follows the narcissistic abuse cycle: love bombing during campaign season (“I am your voice,” “I alone can fix it”), followed by devaluation once power is secured, then hoovering when the next election requires mobilisation. Survivors of family narcissism often report feeling re-traumatised by political systems because the dynamics are genuinely the same—optimised by focus groups rather than individual intuition, but structurally identical.

We may be living in an era of narcissistic institutions—systems that have adopted the psychological architecture of personality disorder as their operating logic. When institutions operate narcissistically, individual narcissistic leaders do not represent aberrations but natural products of systems that select for and reward their traits.

Hugo Chávez in Venezuela offered the same vicarious narcissism to barrio residents that Trump apparently offered rally crowds: the powerful attacks on “the oligarchy,” the sense of participating in revolutionary destiny, the validation of belonging to the chosen people. Mao’s Cultural Revolution, Pol Pot’s Year Zero each combined genuine grievance with grandiose promises that justified any means. The narcissistic leader’s certainty that they alone understand history’s direction appears whether that direction points backward to lost greatness or forward to revolutionary transformation. “Make America Great Again” and “Workers of the World Unite” appeal to different constituencies but offer the same psychological bargain: merge with a grandiose movement, and your individual insignificance dissolves into historical destiny. The wound addressed differs—lost supremacy on the right, systemic oppression on the left—but the salve is identical: a leader who promises that you are special, your enemies are evil, and your victory is inevitable.

Lifton 742 identified this nation level ‘splitting’ dynamic in his study of thought reform. He called it “ideological totalism,” the all-or-nothing thinking that makes partial disagreement feel like total betrayal. Once fully invested in a movement, admitting error on any point threatens the entire structure of meaning the movement provides. The sunk costs (damaged relationships, defended positions, years of emotional investment) make exit psychologically expensive even when continued membership has become untenable.

The parallel to cult dynamics is well documented. Galanter 435 found that charismatic groups provide what he called “relief effect”—reduction in anxiety and depression upon joining that creates powerful attachment. The strongman’s rallies function similarly. Burgo 177 describes them as exercises in “narcissistic symbiosis”: the leader receives Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. from the crowd’s adulation while followers experience what Durkheim called “collective effervescence”—the heightened emotional state of group ritual that temporarily dissolves individual boundaries. Participants leave feeling energised, important, connected—feelings ordinary politics rarely provides.

Erving Goffman’s analysis of “total institutions”—prisons, asylums, military units—provides the architectural template for understanding what happens when these dynamics become encompassing. 460 Goffman documented the “mortification of the self”: a systematic process of stripping away the individual’s prior identity to ensure institutional compliance. The recruit’s civilian clothes are replaced with uniforms; personal possessions are confiscated; former roles and statuses are invalidated; the self is dismantled and rebuilt to serve the institution. In political movements centred on narcissistic leaders, this mortification occurs not through physical confinement but through psychological totalism: the follower’s independent judgement is systematically invalidated until the leader’s reality becomes the only reality. The agency of the follower is not merely suppressed but structurally dismantled deliberately over time—the “agentic state” that Milgram identified as situational becomes, in these contexts, a permanent restructuring of the self. Consider drill sargents in the military. What begins as voluntary allegiance ends as something closer to identity capture.

Maria, a former supporter, gave a description of life feeling “flat” after leaving a political party that reveals the theft at the heart of this transaction. She gave years, relationships, her professional credibility, her family connections—and received in return a temporary sense of belonging that evaporated the moment she stopped providing Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. . This will sound familiar to supporters from all political backgrounds. The politician took her contributions and offered nothing sustainable in return. This is the same asymmetry survivors of narcissistic relationships describe: they gave everything, received promises, and discovered too late that the relationship was extraction disguised as exchange. The political version just amplifies the extent of the theft: millions of citizens contributing money, trust, attention, civic engagement, and emotional investment to a system designed to benefit one figure and their inner circle.

The Narcissistic Situation

In 1990, a reporter for Playboy magazine asked Donald Trump whether he was the same person he’d been in first grade. “When I look at myself in the first grade and I look at myself now,” Trump replied, “I’m basically the same” 1243 . The interviewer treated this as evidence of consistency. Clinicians who later examined the quote noted that such a claim—being “basically the same” since age six—describes a pattern that, in clinical settings, would raise questions about developmental arrest.

We must be careful here. Speculating about whether any public figure meets clinical criteria for narcissistic personality disorder risks violating the Goldwater Rule, and for good reason. But there is a deeper problem: Trump has long been aware that observers consider him “narcissistic,” and has proven adept at dropping what might be called attention bombs—provocative statements that evoke predictable responses and expand presence in public consciousness. Every hour experts spend debating the psychology of such figures is an hour their image dominates discourse. This is precisely the trap this work seeks to avoid. The fact of the attention bomb is worth exploring, and it’s structure, but not the particular figure itself.

What matters is that these schemes for grabbing attention surround such figures—they are part of a calculated system that works to ensure they remain central in the public eye. This requires others to orient their attention towards them, often involuntarily, and insists the public persona is a factor in ordinary people’s lives. The system is a distraction and by stealing attention damages families, exhausts citizens, and erodes democratic norms. The politician is ultimately disposable, and the personality cult around them is transient. The wasted time, the unwarranted mental labour, the lack of closure, and the other costs of engaging with a narcissistic individual or the system of fortifications that surrounds them is the cost of trying to relate to something that cannot relate properly in return. This is why they are best seen as not individuals (who are not accessible past a public persona) but merely ‘narcissistic situations’.

This “narcissistic situation” is not a diagnosis of any individual, but at a national level a description of the system that emerges when political culture centres on figures displaying these narcissistic patterns. Whether reality distortion reflects clinical pathology or strategic performance matters less than its systemic effect: a political environment where shared reality erodes, where truth becomes tribal, where citizens must expend unnecessary energy simply maintaining contact with verifiable fact.

Svetlana Alliluyeva, Stalin’s daughter, described the same dynamics from within her father’s inner circle. “He saw enemies everywhere,” she wrote in her memoir, smuggled to the West after her defection. “It had become an obsession.” Her memoir Twenty Letters to a Friend—written in the Soviet Union and smuggled out upon her defection—provides the only intimate family perspective on Stalin’s private behaviour 21 . Nikita Khrushchev, who served in Stalin’s inner circle for decades, confirmed the pattern in memoirs dictated after his removal from power: “Everything was distorted. If Stalin said something, everyone agreed. To disagree was to sign your own death warrant” 663 . The inner circle lived in perpetual terror, summoned to late-night dinners where Stalin would force them to drink until they collapsed, watching for signs of disloyalty in their slurred words.

Understanding the situation rather than diagnosing the individual has practical implications. Appeals to the narcissistic leader’s better nature are likely futile, because the defensive structure makes such appeals literally unreceivable. What works, the literature suggests, is structural constraint—institutions that check power and citizens who refuse to participate in reality distortion. The narcissistic leader will resist these constraints, experience them as persecution, rage against them. But the constraints themselves do not require the leader’s cooperation to function.

The Malignant Narcissist’s Playbook

In 1984, Otto Kernberg published a clinical paper distinguishing ordinary narcissistic personality disorder from what he termed “malignant narcissism” 650 . The distinction mattered clinically: while both involved grandiosity and empathy deficits, malignant narcissism added what Kernberg called “ego-syntonic aggression”—cruelty that feels natural and justified rather than shameful, colloqually termed as sadism. Post 1003 , applying this framework to political leaders, found the distinction useful for identifying patterns in how regimes affect people in everyday life subject to their power.

The regimes of Saddam Hussein, Kim Jong-il, and Idi Amin each displayed the observable characteristics of this malignant pattern. In Iraq, the regime demanded continuous public displays of loyalty—portraits in every home, mandatory attendance at rallies, informants in every neighbourhood—while ordinary citizens faced arbitrary detention, torture, and execution for perceived disloyalty; the 1988 Anfal campaign killed an estimated 50,000–182,000 Kurdish civilians 576 . In North Korea, the regime constructed an elaborate personality cult requiring citizens to bow before statues, maintain portraits of the Kims in their homes, and participate in organised weeping upon the leader’s death—while an estimated 400,000 people died in political prison camps and millions starved during famines the regime denied 575 . In Uganda, Amin’s regime broadcast executions on television, required civil servants to carry the dictator on a sedan chair, and made praise of the leader a condition of survival—while an estimated 100,000–500,000 civilians were killed 28 . The pattern is consistent across these cases: grandiose demands for admiration, absence of empathy for suffering, exploitation of other people, and a sense of entitlement to absolute obedience. These are the DSM-5 criteria made visible in the lives and deaths of people with no escape. Notably, these patterns appear across the political spectrum—Mao’s China and Pol Pot’s Cambodia displayed dynamics identical to Hitler’s Germany, differing only in ideological content. This reinforces the observation that tactics follow characterise narcissistic movements regardless of whether they march under red flags or nationalist banners.

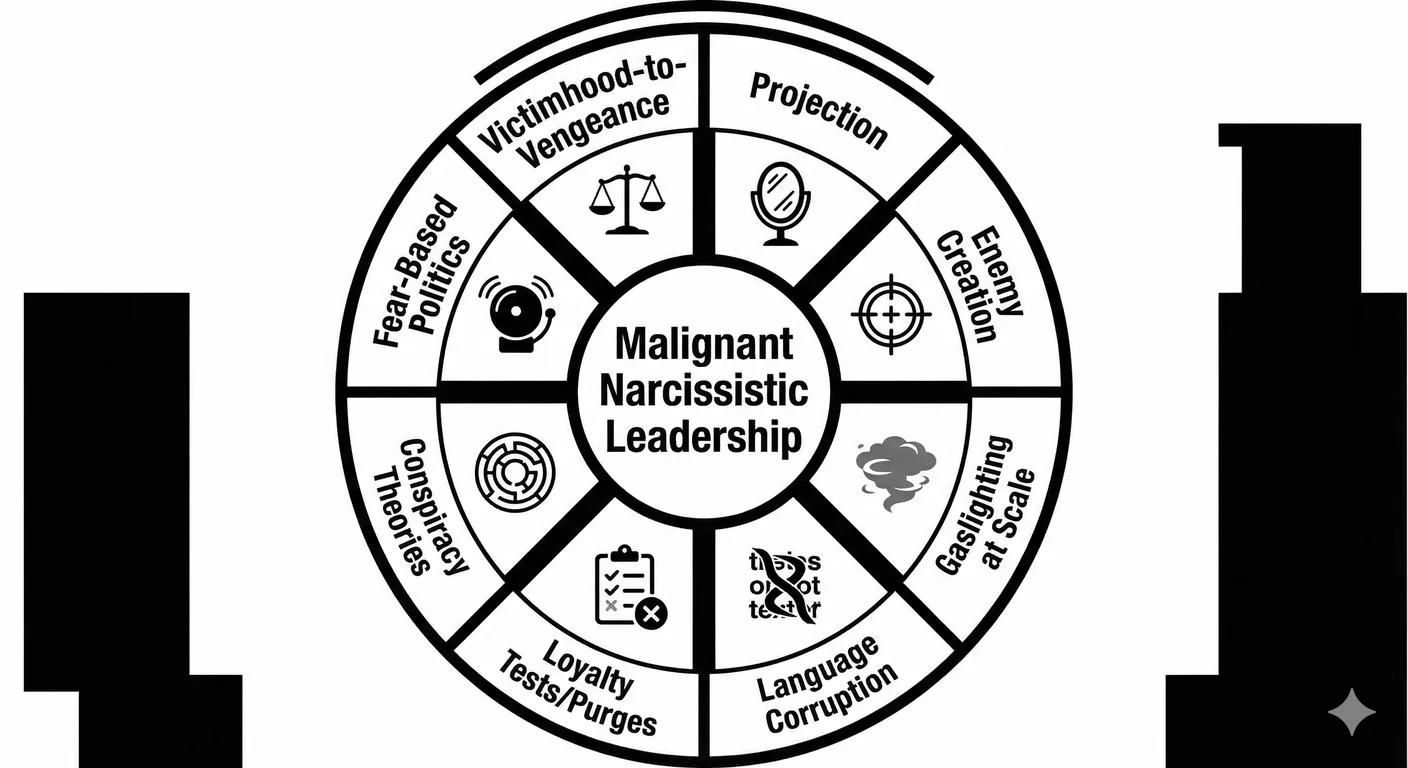

The patterns documented by Post repeat across authoritarian movements. The first involves what Ben-Ghiat 104 calls the “victimhood-to-vengeance pipeline.” He found consistent narratives combining persecution and power. The leader claims to be simultaneously victim and victor, humiliated by enemies yet destined for greatness. This duality serves strategic functions—justifying aggressive actions as defensive while deflecting accountability by reframing criticism as persecution. We saw this tactic earlier in corporate and family circles.

Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. forms another core defensive mechanism of malignant narcissism at the national scale. In 2020 research by Cruz and colleagues 280 found that Trump consistently accused others of exactly what he was doing—claiming elections were rigged while attempting to rig them, and also accusing others of corruption while profiting from office. This is not simple hypocrisy but psychological necessity: a narcissist cannot bear awareness of their own flaws and will evacuate them into others. Klein 669 called this “ Projective Identification Projective Identification A defense mechanism where one person projects unwanted parts of themselves onto another, then manipulates the other to behave in accordance with the projection. Common in narcissistic dynamics where victims come to feel the narcissist's disowned shame and inadequacy. ”—forcing others to embody the narcissist’s disowned aspects. This is indicative of the absence of self discussed earlier. An integrated self would be able to understand, accept, and integrate the awareness of the flaws as a means towards natural and reliable repair. The inability to do so and the presence of reactive projecting indicate no underlying self exists to integrate.

Dr Vamık Volkan describes how narcissistic leaders need “ chosen trauma s” and “chosen enemies” to maintain group cohesion and justify their authority 1279 . Trump cycled through enemies, Hillary Clinton, the media, immigrants, China, Antifa, always maintaining a threat requiring his protection. These enemies serve as repositories for projected badness while providing external explanation for any failures. The narcissistic leader’s paranoia creates real enemies through aggressive behaviour, creating self-fulfilling prophecies that validate their persecution beliefs.

Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. —the manipulation technique explored in Chapter and at family scale in Chapter —scales from individual to societal level under malignant narcissistic leadership. Welch 1311 describes “State of Confusion” where entire populations begin doubting their perception of reality. When Trump claimed COVID would “disappear” while thousands died daily, when he declared victory in an election he lost, when he called January 6th a “peaceful protest”, these were not just lies but historic attacks on shared reality itself. The goal is not necessarily belief but exhaustion. Wearing down citizens with the specific aim creating what Hannah Arendt called “the ideal subject of totalitarian rule”—people who can no longer reliably distinguish true from false. 43

Stanley 1171 identifies how authoritarian leaders empty words of meaning through overuse and inversion. “Fake news” originally described actual disinformation but became Trump’s label for any unfavourable coverage. “Patriot” became those who attacked the Capitol. “Freedom” meant refusing public health measures. This linguistic rebranding prevents coherent discussion of actual issues while allowing the narcissist to mean whatever serves their immediate needs through a process termed Funnel Compartmentalisation. By rebranding terms for the public audience, one creates funnelled variants of axial terms and can maintain control over meaning audience by audience and instantiate the conditions for ongoing tension and triangulation between them. This can be used as a loyalty test as well as an escape hatch to the next attention bomb.

Loyalty tests and purges maintain the narcissistic leader’s control while feeding their paranoia. Trump’s presidency featured constant turnover as officials publicly failed loyalty tests. Sometimes by refusing to prosecute enemies or acknowledging election results. Altemeyer 25 describes how authoritarian leaders create “loyalty spirals”, each purge requiring greater submission from survivors, leading to increasingly extreme behaviour.

The use of conspiracy theories delivers the malignant narcissist with another tool. Uscinski 1263 found that susceptibility to conspiracy theories correlates with both narcissistic traits and support for narcissistic leaders, creating “conspiracy communities” bound by shared alternative reality. Conspiracy theories serve narcissistic leadership by providing external explanations when reality contradicts grandiosity. The “deep state” or “secret cabal” narrative functions as collective externalisation of the narcissist’s psychic defences: every setback becomes sabotage, every criticism confirms persecution, every constraining institution becomes enemy territory. Millions of followers who find their own frustrations explained by the same conspiracy become bound to the leader who named the “hidden” enemy.

Fear-based politics delivers these leaders’ essential fuel. Aristotle observed that Greek tyrants maintain power by keeping citizens in “perpetual alarm”—too frightened to organise resistance. Modern narcissistic leaders refine this insight, targeting specific groups as existential threats requiring strongman protection. The pattern repeats globally—Orbán’s Muslims, Modi’s Muslims, Bolsonaro’s leftists. Each designated enemy serves the same psychological function: transforming complex social problems into simple narratives of invasion and contamination that only the strong leader can address.

The scapegoating mechanism connects political narcissism to its darkest historical precedents. Hitler’s Jews and Stalin’s kulaks—these regimes share the pattern: identification of internal enemies whose suffering is presented as instrumental for national restoration. This is theft conversion at its most lethal: the genuine suffering of ordinary citizens converted into hatred of designated others, generating the loyalty and murderous labour that the regime requires—at minimal cost to the regime except rhetoric, and at horrific cost to both scapegoats and the followers whose real problems remain unaddressed.

The political narcissist’s tendency towards splitting—viewing people as all-good or all-bad—finds expression in such ideology. Jews become vermin; kulaks become class enemies; Tutsis become cockroaches. This dehumanisation removes empathic barriers to violence: they are not really human, so normal moral constraints do not apply. Rights can be stripped away or ignored.

It provides a permanent scapegoat for all problems: everything wrong results from their existence. And it offers simple solutions: eliminate them and utopia arrives. The narcissist’s inability to tolerate ambiguity or accept partial solutions manifests as the demand for total elimination.

The twentieth century’s genocides—the Holocaust, the Holodomor, the Cambodian killing fields, Rwanda—each arose from complex historical factors, yet examining perpetrator psychology reveals recurring narcissistic elements. Genocide exemplifies the ultimate narcissistic fantasy: absolute power to decide who deserves existence.

The pattern extends back millennia. In 40 CE, the philosopher Philo of Alexandria stood before the Emperor Caligula, pleading for his people’s rights. Caligula received the Jewish delegation while inspecting garden renovations, forcing elderly delegates to follow him from room to room, mocking their dietary laws while courtiers laughed. “We were in the situation of men who had been deprived of all hope,” Philo later wrote. “He was carried away by his passions and there was no one who could restrain him.” Philo’s Legatio ad Gaium (Embassy to Gaius)—the only surviving eyewitness account of Caligula’s behaviour from someone who met him personally—documents this encounter 985 .

What struck Philo most was Caligula’s complete inability to perceive them as real people—they were props in his theatre. Two thousand years later, the pattern persists: the system effects suffering on targeted people through measures designed to extend the false self of the persona in charge. This is psychological preparation for violence, beyond mere rhetoric; the natural empathy for neighbours, people in the street, must be denied before their elimination can be contemplated.

The performance through cruelty distinguishes malignant from merely grandiose narcissism. Family separation at the border, withholding aid from blue states during Covid, tear-gassing peaceful protesters, these were dominance displays, not merely policy choices. Serwer 1119 identified “the cruelty is the point”, suffering inflicted on designated enemies provides pleasure to both leader and followers. This sadistic element, what Fromm 427 called “necrophilia”: the love of death and destruction—marks the malignant narcissist’s ultimate dangerousness.

The Follower’s Bargain

The relationship between narcissistic leaders and their followers embodies a complex psychological transaction that goes beyond simple manipulation or deception. Followers are not merely victims but active participants in what Post 1003 calls “the leader-follower lock”—complementary psychological needs that create powerful mutual dependency. Understanding why millions choose to follow obviously narcissistic leaders, often against their material interests, requires examining the psychological benefits followers receive and the prices they pay.

Lipman-Blumen 753 identifies the “allure of toxic leaders”—paradoxical attraction to leaders who harm followers’ interests. She describes “the psychological benefits of followership”, distinct from masochism: anxiety reduction through submission to strong authority and identity through membership in special groups. The narcissistic leader offers all three intensely—absolute certainty that calms anxiety, world-historical importance that provides meaning, and chosen people status that confers identity.

The concept of “malignant normality” explains how followers adapt to narcissistic leadership 744 . Dangerous, abnormal behaviour becomes accepted as ordinary through repetition and social acceptance; what would previously have been scandalous gradually becomes “just how things are,” eroding the capacity for moral outrage. Political supporters who were initially disturbed by his behaviour came to see it as strategic brilliance. This incremental accommodation—each accepted transgression making the next easier to rationalise—differs from sudden conversion. It works best if these events happen quickly, almost daily allowing enough time for identification but not enough to process or resolve so they become normalised and expected, and affect so many people the impact of the leader is hard to ignore. It numbs the citizen, forcing them to reduce their empathy for others. Allowing and defending such events which become progressively closer to atrocities. Dr Lifton compares this to the “atrocity-producing situation” where ordinary people commit terrible evil through gradual normalisation.

Followers develop what Shaw 1131 calls “traumatic narcissism”, identifying with the aggressor to avoid becoming victims. By aligning with the narcissistic leader, followers access vicarious power while protecting themselves from becoming targets. Supporters at rallies chanting “Lock her up” or “Send them back” were participating in collective aggression that made them feel powerful, beyond merely supporting policies. They were echoing the sentiments at rallies in the 1930s where “Lock them up” and “Send them back” were shouted in Germany. The psychological high of shared hatred, what Bollas 134 calls “loving hate,” becomes addictive.

The sunk cost fallacy intensifies follower commitment even as evidence of the leader’s pathology accumulates. Tavris and Aronson 1212 describe “cognitive dissonance reduction”, the psychological need to justify past decisions by deepening commitment. Political supporters who sacrificed relationships, reputation, or resources for their support could not easily admit error. Instead, they doubled down, interpreting each scandal as proof of deep state persecution, each failure as strategic brilliance. The greater the investment, the harder it becomes to acknowledge mistake.

The role of humiliation in follower psychology proves particularly important. Nathanson 906 identifies “humiliated fury”—rage arising from shame that seeks restoration through violence or domination. Many disgruntled supporters described feeling humiliated by coastal elites, educated professionals, and cultural changes that made them feel backward. The narcissistic leader offers policy solutions and emotional redemption alike, turning humiliation into pride, shame into rage, victims into victors. That meant making humiliated people feel great again.

Gender dynamics in follower psychology reveal complex patterns. Manne 794 describes how some women support misogynistic leaders through “himpathy”—excessive sympathy extended to powerful men accused of wrongdoing that redirects concern from victims to perpetrators. Women at Trump rallies wearing “Trump can grab my pussy” shirts were not debasing themselves but signalling agency through alignment with power.

The digital architecture of follower communities creates what Marwick 804 calls “morally motivated networked harassment.” This is the same parasocial system we saw earlier in the corporate world. Supporters on social media do not just defend political narcissists but actively attacked critics through coordinated harassment campaigns. This is not always top-down direction but can include emergent behaviour—followers competing to perform loyalty through visible aggression. The dopamine hits from likes and shares for attacking enemies created addictive cycles that bound followers to increasingly extreme behaviour. The collective element and associated validation play an integral role.

The cumulative effect is theft—the same theft that operates in narcissistic families and workplaces, now at societal scale. The follower surrenders independent judgement through reality distortion and ultimately their autonomous self, subsumed into the leader’s grandiose project. In return, they receive the same counterfeit currency narcissistic systems always offer: conditional belonging that evaporates the moment supply wavers. The Trauma Bonding Trauma Bonding A powerful emotional attachment formed between an abuse victim and their abuser through cycles of intermittent abuse and positive reinforcement. that makes departure feel impossible and the Triangulation Triangulation A manipulation tactic where a third party is introduced into a relationship dynamic to create jealousy, competition, or to validate the narcissist's position. that turns former allies into enemies—these are the same mechanisms that trap survivors in narcissistic marriages and children in narcissistic families. The political narcissist simply operates the extraction at industrial scale, with media amplification replacing kitchen-table manipulation and rally crowds replacing family dinners. The intimacy differs; the theft is identical.

Purity Spirals: Narcissistic Dynamics in Progressive Spaces

Narcissistic patterns also manifest in progressive contexts, though the content differs while the psychological architecture remains identical. Understanding this is essential for two reasons: first, intellectual honesty requires acknowledging that pathological group dynamics are not confined to any one political position; second, recognising these patterns across ideological lines helps identify what makes them dangerous independent of political content.

Purity spirals occur when groups compete to demonstrate ideological commitment through increasingly extreme positions 765 . What begins as legitimate concern about racism, sexism, or other injustice can transform into what Pluckrose and Lindsay 998 call “applied postmodernism”—an unfalsifiable framework where disagreement itself perversely becomes evidence of the moral corruption being alleged. The narcissistic element emerges when the spiral becomes about demonstrating one’s own virtue rather than addressing actual harm. We see this when callouts serve status competition rather than justice itself. This is the threshold when nuance becomes betrayal and good faith becomes impossible.

The psychological dynamics mirror narcissism by splitting allies versus oppressors with no middle ground, and a demand for total loyalty. A progressive activist who questions whether a particular callout was proportionate may find themselves labelled complicit in oppression. The content differs but the binary thinking, the inability to tolerate ambiguity, the transformation of disagreement into moral failing—these are narcissistic patterns regardless of political valence.

The phenomenon of “luxury beliefs” that Henderson 541 describes—where affluent progressives adopt positions that impose costs primarily on working-class communities—shows how easily narcissistic gratification can masquerade as social justice. The psychological reward of feeling morally superior while identifying and condemning the unenlightened provides the same vicarious narcissism that all such movements offer through different content. Advocating for policies whose costs one will never bear, while condemning those who raise practical concerns as morally deficient, displays the empathy deficit and grandiosity that define narcissistic patterns.

Former progressive activists who have left such movements describe trajectories closely similar to those exiting right-wing extremism: the same sense of mission and clear moral categories, the same silencing of dissent reframed as evidence of moral failing, the same either/or thinking that makes complexity feel like betrayal. The psychological satisfaction of destroying designated enemies operates identically whether the target is labelled a “libtard” or a “racist.” The narcissistic pathology requires enemies; it does not care what ideology designates them.

A former activist in a prominent social justice organisation describes her exit: “I joined because I genuinely cared about racial equity. For a while it was meaningful work. But gradually, the focus shifted from helping communities to policing each other’s language and rooting out insufficiently committed members. I watched colleagues destroy a woman’s career over a clumsy but well-intentioned comment. When I said the punishment seemed disproportionate, I was told my discomfort was ‘white fragility.’ Within a month I was pushed out too.” She pauses. “The weird thing is, the dynamic felt familiar. I’d grown up with a narcissistic mother—the whole walking on eggshells thing, the sudden rage, the way questioning anything meant you were the problem. I’d traded one system automatically for another without recognising they were alike.”

Democratic Institutions Under Siege

Democratic institutions assume good faith. The American founders’ “ambition counteracting ambition” presumed rational actors who might be self-interested but would ultimately accept constraints. They did not anticipate leaders who would rather destroy institutions than accept limits. This collision creates what Levitsky and Ziblatt 731 call “how democracies die”—through gradual erosion by leaders who follow law’s letter while violating its spirit.

The assault follows predictable patterns. First: delegitimise opposition. Trump’s “enemy of the people” for journalists and “treasonous” for Democrats who did not applaud represent narcissistic necessity, beyond mere rhetoric. The grandiose self-concept finds legitimate opposition intolerable. Second: capture courts. Scheppele 1090 documents how Orbán packed judiciaries through technical changes rather than dramatic purges. Trump appointed over 200 federal judges, many rated “unqualified” but loyal to executive power. Third: corrupt oversight. Trump fired five inspectors general in six weeks and claimed “absolute immunity.” Kendzior 644 calls this “accountability theatre”—processes that appear to check power while demonstrating the leader’s ability to survive them.

The civil service becomes a particular target. The narcissistic leader experiences any independence as disloyalty, any expertise as threat. Staff and legislators learn to manage around the leader rather than check him, treating tantrums as weather to be avoided. Those who join believing they can constrain from within find themselves compromised, forced to enable or resign. The separation of powers collapses into co-dependent enabling.

Some resilience emerged at state level. Governors resisted pandemic denialism while secretaries of state refused to “find” votes. Bulman-Pozen 176 calls this “partisan federalism.” But it depended on individuals choosing institutions over party, a choice narcissistic pressure made increasingly costly.

The media proved both accelerant and brake. Trump generated an estimated $5 billion in free coverage through controversy, according to mediaQuant analysis reported during the 2016 campaign 928 —the business model of journalism aligned perfectly with narcissistic spectacle. Yet investigative reporting exposed corruption while documenting lies. The attention economy that elevated him also, eventually, documented his unfitness.

International institutions fared worse. Trump’s withdrawal from international agreements reflected narcissistic inability to accept constraints. Ikenberry 588 describes “the end of liberal international order”—systems that constrained state behaviour collapsing under leaders who recognise no authority beyond themselves.

What citizens experience through this institutional degradation is theft of the shared civic relationship. Democratic institutions represent accumulated trust—generations of citizens who accepted electoral losses and constrained their own power because they believed others would do the same. This trust is a commons, built collectively over centuries and maintained through mutual restraint. When narcissistic leaders capture these institutions, they convert shared patrimony into personal property. Courts become instruments of vengeance rather than justice. Agencies become tools of reward and punishment rather than public service. The accumulated trust of generations becomes fuel for one figure’s aggrandisement. Citizens who notice this conversion experience the same disorientation as children who discover their family was never mutual—that while they were contributing in good faith, someone else was extracting. The institutional version of this theft leaves the same wreckage—exhaustion and the corrosive suspicion that every relationship might be parasitic. The narcissistic leader’s assault on institutions is the public version of what narcissistic parents do to family trust and what narcissistic partners do to intimacy. The scale differs; the theft is the same.

The patterns we trace are not new—they merely find new expression in each generation. Northern Ireland’s Troubles (c. 1968–1998)—a thirty-year conflict between unionists and nationalists that claimed over 3,500 lives, largely ended by the 1998 Good Friday Agreement though sectarian tensions persist—offer a case study in how narcissistic leadership exploits communal division.

William, now seventy-three, was nineteen when Ian Paisley came to his East Belfast shipyard. “He didn’t just speak—he roared. You felt it in your chest. After he finished, men were weeping, swearing oaths. I’d have died for him that night.” Paisley gave them enemies: “The Pope. Dublin. Lundys and traitors. Anyone who saw Catholics as human was suspect.” William’s disillusionment came when his son, raised on that rhetoric, killed a Catholic teenager. “That boy’s father worked in the shipyard with me. I’d known him twenty years. And my son murdered his child because Paisley told us Catholics weren’t really human.” He pauses. “Paisley never killed anyone himself. He just made killing possible. Made it feel righteous. That’s what these men do. They give permission.”

Across the sectarian divide, Séamus tells the mirror image story. The former IRA prisoner joined at seventeen after his uncle was interned without trial. “Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness—they gave that rage a shape. We weren’t thugs; we were freedom fighters. They were brilliant at it, making you feel part of history.” His turning point came years after the ceasefire, meeting a prison officer he’d hated. “He’d been terrified every day of work. He had children. He cried when prisoners died. That broke something in me—the narcissism of believing we were purely good and they were purely evil.”

Both now work in reconciliation, often together. “We were mirror images,” Séamus reflects. “Both given enemies to hate by leaders who profited from our hatred.” William adds: “The leaders moved on. Paisley made peace eventually, shook hands with McGuinness, laughed together like old friends. But the boys we buried, on both sides, they stayed dead. We paid for their glory.” This illuminates the narcissistic system’s essential inequality: the leader receives supply—adulation, power, historical significance—while followers pay in blood. When the political calculus shifted, the leaders could become friends because they’d always understood, at some level, that it was performance. The true believers had no such flexibility.

“The young lads being radicalised now: online, by Trump or whoever, they’re us fifty years ago,” William says. “Same fears, same promises, same permission to hate. The technology’s different. The psychology’s identical.”

The Aftermath and Recovery

The departure of a narcissistic leader does not end their impact. Like family systems recovering from narcissistic abuse, democracies experience what Herman 546 calls “post-traumatic stress”—ongoing dysfunction even after the immediate threat passes. The narcissist’s inability to accept defeat means they remain psychologically present even when formally absent from power, what Ben-Ghiat 104 calls “authoritarian afterlife.”

“Democratic backsliding” often accelerates after narcissistic leaders leave office. Bermeo 109 found that norms violated during narcissistic rule rarely fully recover; each transgression establishes a new baseline of acceptable behaviour. Opponents respond with their own norm erosion, justifying it as necessary response. Nyhan 927 calls this “the death spiral of democracy”—reciprocal norm violation that continues independent of any particular leader.

The “Lost Cause” mythology that emerged after the American Civil War provides historical parallel. Just as defeated Confederates created elaborate mythology recasting their rebellion as noble cause, supporters of defeated narcissistic leaders construct narratives of stolen elections and hidden persecution. Cox 272 illustrates how Lost Cause mythology poisoned American politics for over a century. Similar mythologies emerging around defeated narcissists globally may likewise distort politics for generations. The narcissist’s alternative reality persists, preventing the shared truth necessary for reconciliation.

Those Who Stayed and Fought

Election workers across America faced similar ordeals. A Brennan Center survey 156 found that 38% of local election officials reported experiencing threats, harassment, or abuse; 54% worried about the safety of colleagues. Twenty percent planned to leave before the 2024 election, creating a crisis of expertise precisely when democratic institutions most needed defending. The narcissistic leader attacks not just laws but the people who implement them, creating cascading failures as experienced civil servants flee. The system wins by exhausting resisters until they withdraw—conversion unnecessary. Each experienced election worker who quits, each journalist who leaves the profession, each civil servant who takes early retirement, embodies a small victory for narcissistic governance, the systematic destruction of institutional competence that makes democracy function.

January 6, 2021: Tom, a Capitol Police officer with twenty years’ experience, stands in civilian clothes across from me. He has been diagnosed with PTSD since the insurrection and takes medication for anxiety he never had before. His story offers ground-level perspective on democracy’s fragility, and the human cost of defending it against narcissistic assault.

“I’ve been a cop for twenty years. I’ve handled protests, riots, violent situations. Nothing prepared me for that day.” He stares at his coffee. “The violence was bad enough. And also the faces. These weren’t antifa or professional agitators. These were people who looked like my neighbours, my relatives, my high school classmates. Middle-aged guys in Trump gear. Women who could’ve been my mom’s friends. They were trying to kill us: literally, kill us, while screaming about patriotism.”

What haunts Tom is not the physical trauma but the psychological dissonance. “I took an oath to defend the Constitution. So did they, in their minds. They were convinced they were saving America from a stolen election. I was convinced I was saving America from a mob. We couldn’t both be right.” He pauses. “The hardest part is knowing some of them are still out there, still believing, still waiting for another chance. And some of my colleagues have left the force because they agreed with the mob. The thin blue line went right through my department.”

Tom’s experience illuminates the reality distortion that narcissistic leaders create. “Trump told them the election was stolen. They believed him. Not because they’re stupid, some were doctors, lawyers, business owners. Because they wanted to believe. Because he made them feel like warriors instead of citizens. Because the lie was more exciting than the boring truth that they’d just lost a normal election.” This analysis matches Lifton’s concept of solipsistic reality—followers choosing the leader’s grandiose narrative over mundane democratic reality.

The aftermath has been its own ordeal. “I testified before Congress. I’ve had death threats. My kids had to change schools. My marriage almost fell apart, how do you explain to your wife why you can’t sleep, why you flinch at loud noises, why you drink more than you used to?” He looks up. “The officers who died, one from suicide, they’re not even on the official casualty list because they didn’t die on the day. But January 6 killed them. The narcissist doesn’t just hurt his enemies; he breaks the people who try to stop him.”

Tom, nevertheless, ends with something like hope. “We held the line. The building stood. The votes were counted. Democracy survived: barely, but it survived. That matters.” He connects his experience to the book’s larger themes: “I grew up with a narcissistic father. Thought I’d escaped that world. Turns out it just went national. But I’ve learned something from both experiences: narcissists seem invincible, but they’re actually fragile. They depend on everyone else being too scared or tired to say no. On January 6, we said no. A lot of regular people: cops, staffers, election workers—said no. That’s how you beat them. With enough ordinary people refusing to break, no need for someone bigger and meaner.”

Tom’s observation about his narcissistic father provides the chapter’s key bridge between personal and political narcissism. The patterns are the same across scales: the grandiosity that cannot tolerate contradiction, the rage when reality intrudes, the willingness to destroy rather than accept limits. What Tom faced on January 6 was his family system writ large—millions of people acting out the dynamics he’d spent his childhood surviving. His PTSD comes from the violence and from the recognition alike: this is what it looks like when the individual has a nation instead of a household.

Tom’s survival illustrates the palace’s resilience. Having escaped one narcissistic system, his family, he had built a stable identity grounded in professional competence. When the maze came for him on January 6, he had something to stand on. “I took an oath to defend the Constitution”—that oath, internalised and made part of his identity, delivered the palace architecture that let him hold the line when maze-dwellers demanded he join them. The rioters, lost in their own mazes, could not understand someone who would risk death for an abstraction like constitutional order. They expected everyone to be as lost as they were, as desperate for belonging, as willing to trade integrity for tribal membership. Tom’s palace, built painfully from the wreckage of his childhood, proved stronger than their collective maze.

His insight about fragility deserves emphasis. Narcissistic systems appear invincible but depend entirely on compliance. The narcissistic parent’s power dissolves when the adult child stops seeking approval. The narcissistic boss’s authority crumbles when enough employees refuse to enable. The narcissistic leader’s grip loosens when institutions and individuals say no. This is not naive optimism, Tom’s scars prove the cost of resistance, but it is the core truth about narcissistic power: it requires constant feeding and collapses without it.

The trauma Tom carries—hypervigilance and damaged relationships—mirrors the aftermath of narcissistic abuse. His body remembers what his mind tries to process. The officers who died by suicide in the months after January 6, who are not on the official casualty lists, represent what Boddy documented in Chapter 8: the invisible toll that narcissistic systems exact on those who resist them. The damage extends far beyond the immediate event, rippling through families, careers, and psyches for years.

Tom’s survival, despite this trauma, also offers instruction. Priya rebuilt after the family business. Antoine found peace in his Bristol kitchen. Rachel now facilitates recovery groups in Ohio. Like them, Tom has transformed trauma into purpose. His willingness to testify, to speak publicly despite death threats, to name what happened, exemplifies the democratic equivalent of breaking the narcissistic family’s code of silence. The narcissist depends on shame keeping victims quiet. Every voice that speaks anyway weakens that power.

Prevention and Resistance

William and Séamus found their way to reconciliation. But many people cannot leave. They are embedded in families and communities where narcissistic systems hold sway. They must stay and fight.

And here lies a danger that requires naming. Those forced to fight often reach for the weapons at hand—the same instruments of manipulation and willingness to win at any cost that were used against them. The abused child evolves into the abusive parent. The bullied employee evolves into the bullying manager. The population traumatised by one narcissistic leader embraces another who promises vengeance. The cycle perpetuates. The pattern replicates itself through reaction as surely as through repetition.

Recognition alone is not enough. Reclaiming the self (building the palace rather than running frantically through the maze) is the only foundation from which genuine resistance becomes possible. Response over reaction. Meeting cruelty with something the narcissistic system cannot comprehend: firm steps on solid ground. Decency that does not require the other side’s cooperation. Boundaries that hold without hatred. Truth-telling that seeks justice rather than revenge.

For those who never followed but must now rebuild damaged institutions: prosecuting crimes prevents impunity; changing systems prevents recurrence. Neither alone is sufficient. Democracy must learn from its near-death experience without becoming so defensive it abandons the openness that defines it.

With these cautions in mind, what can societies actually do? While narcissistic leaders will likely always exist, we can develop resilience against their rise and resistance to their rule. Berman 108 argues democracies must become “militant” in defending themselves, through conscious, structural protection of democratic values.

The conditions that create vulnerability to narcissistic appeals are what Acemoglu and Robinson 7 call “the narrow corridor” where democracy survives between anarchy and authoritarianism. Reducing inequality and strengthening institutions—this is the slow, unglamorous work that makes populations less susceptible to grandiose promises of simple solutions. Finland’s thorough approach to teaching citizens to identify disinformation offers a model; Pomerantsev 999 found Finnish citizens markedly more resistant to propaganda than other Europeans. Civic education that includes understanding psychological manipulation could inoculate against narcissistic appeals. Sandel 1083 calls this teaching “civic virtue”: the ability to recognise and resist demagogues.

The attention economy that rewards narcissistic behaviour demands reform. Attention is currency—every click on outrage content and every minute of hate-watching funds the system that elevates narcissists. Starve the beast. Support quality journalism. Curating information environment like our mental health depends on it, because it does. At the structural level, Vaidhyanathan 1265 proposes treating social media platforms as public utilities, regulating algorithmic amplification of outrage. Pickard 986 argues for “democratic media”—structures prioritising public interest over profit.

Electoral reforms can reduce narcissistic leaders’ ability to gain power. Ranked choice voting prevents extremist minorities from dominating primaries. Campaign finance limits reduce oligarchic support. Drutman 329 proposes proportional representation to break the two-party duopoly that forces voters to choose between a narcissist and an alternative they may also dislike. Once narcissistic leaders gain power, institutional constraints matter. Bauer and Goldsmith 86 propose broad reforms including disclosure requirements and conflict of interest enforcement.

Civil society resistance provides essential constraint. Chenoweth 237 found that sustained nonviolent resistance involving 3.5% of a population has never failed to create political change. The Women’s March, Black Lives Matter, and climate strikes during Trump’s presidency demonstrated resistance capacity. Fisher 395 documents how “the resistance” created new civic infrastructure that outlasted Trump’s first presidency. This is democracy as practice, not spectacle—showing up to local meetings and town halls, the boring infrastructure that narcissists neglect.

International coordination matters too. When narcissistic leaders validate each other, democratic leaders must likewise support each other. The Magnitsky Act of 2012—named after Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who died in custody after exposing tax fraud—targets individuals rather than nations, freezing assets and banning travel. Similar laws have been adopted by Canada, the UK, and the EU, and could extend to those undermining democracy. Daalder and Lindsay 283 propose a “Committee of Democracies” coordinating responses to authoritarian threats.

Ultimately, however, prevention begins with us, with working on our own narcissistic vulnerabilities. The desire for simple answers. The pleasure of righteous anger. The comfort of tribal belonging. The narcissistic leader exploits these tendencies in all of us. Self-awareness is democratic self-defence. The conversations we have at dinner tables and holiday gatherings matter more than we think. Modelling thoughtful disagreement and epistemic humility—these teach democratic citizenship.

Conclusion: Democracy’s Narcissistic Test

The rise of narcissistic leaders across democratic societies represents revelation, exposing vulnerabilities that were always present but rarely so systematically exploited. The democratic assumption that leaders would be constrained by shame or enlightened self-interest proves naive when confronting systems that display no evidence of shame and define self-interest as unlimited self-aggrandisement. Democracy’s openness, designed as strength, becomes weakness when weaponised by those who view compromise as humiliation and constraint as persecution.

The recurring patterns appear at every scale, from family to corporation to nation. The same traits that define clinical narcissistic personality disorder—grandiosity and lack of empathy, entitlement and exploitation—manifest recognisably at every scale. The father who cannot tolerate his child’s independent thought evolves into the CEO who cannot tolerate employee dissent evolves into the leader who cannot tolerate democratic opposition. The mother who gaslights her daughter about childhood memories evolves into the manager who gaslights her team about project failures evolves into the politician who gaslights the nation about election results. The patterns recur because the underlying psychology is identical; only the stage changes.

We can identify narcissistic leadership at any scale: personal, corporate, or political, by the same unmistakable signature: the wreckage they produce, independent of grandiose claims. The narcissistic parent is revealed by the damaged children. The narcissistic organisation is revealed by the traumatised employees. The narcissistic leader is revealed by the eroded institutions and exhausted resisters, the normalised cruelty. Diagnosis from afar is unnecessary; observing the wake suffices. Where there is consistent chaos, consistent blame-shifting, consistent inability to acknowledge error, consistent demand for loyalty that exceeds loyalty to truth—there you will find the narcissistic pattern, however culturally dressed it may be. Once you learn to recognise the pattern at one scale, you can recognise it at all scales.

The very visibility of narcissistic leadership’s damage, paradoxically, creates opportunity for learning and adaptation. Unlike authoritarian systems that hide their failures, democracies conduct their crises in public, creating evidence for reform. The spectacular failure of narcissistic pandemic response and economic volatility under narcissistic leadership provide data points that even supporters struggle to deny. Ben-Ghiat 104 notes that narcissistic leaders often create their own downfall through the very grandiosity that brought them power.

The psychological dimension of democratic citizenship requires new attention. For too long, democracies have assumed citizens were rational actors making informed choices. The success of narcissistic leaders in exploiting psychological vulnerabilities—status anxiety and cognitive biases—reveals that democratic theory must incorporate psychological reality. Haidt 516 argues for “moral psychology” in political science, understanding the emotional and intuitive bases of political behaviour rather than pretending humans are calculating machines.

Collective narcissism—the belief in one’s group’s unrecognised greatness—predicts support for narcissistic leaders who promise to force recognition 1364 . Addressing this requires healing collective wounds—inclusive narratives that provide dignity to all groups and economic policies ensuring material security.

The path forward requires what West 1318 calls “democratic faith”—belief that ordinary people can govern themselves wisely despite evidence to the contrary. This faith is not naive optimism but what Antonio Gramsci called “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”—clear-eyed recognition of democracy’s vulnerabilities coupled with determination to address them. 483 The narcissistic test of democracy is whether it can evolve antibodies to its exploitation while maintaining the openness that defines it.

The question is not whether democracy can survive narcissistic leaders—it has before and will again. The question is what kind of democracy emerges from this test. Will it be what Müller 898 calls “democracy without the people”—technocratic management that prevents popular participation to avoid narcissistic manipulation? Or can we create what Landemore 705 envisions as “open democracy”—systems that channel popular energy towards collective wisdom rather than narcissistic exploitation?

The narcissistic leader promises to make followers great again and restore lost glory. Democracy’s response must be something more difficult than competing grandiosity: the patient work of building systems that provide genuine dignity and real participation. This is not as exciting as the narcissistic spectacle, but it is the difference between sustainable flourishing and spectacular destruction.

The throughline is theft. The narcissistic parent steals childhood; the narcissistic partner steals intimacy; the narcissistic colleague steals professional life; the narcissistic leader steals citizenship. In each case, what should be reciprocal becomes extractive. What should be shared becomes consumed. The victim gives trust and loyalty—and receives in return only the conditional tolerance of remaining useful. When that usefulness ends, so does the relationship’s pretence of mutuality.

And in politics, a second-order theft emerges: theft conversion, where the narcissistic system takes citizens’ genuine grievances—economic displacement and diminished status—and converts these wounds into hatred of designated enemies. The citizen’s pain becomes fuel for the system’s engine. The triangulation and gaslighting of narcissistic families operate at civilisational scale: setting group against group, redirecting legitimate anger towards scapegoats while the actual causes of suffering remain unaddressed. This conversion is cheaper than solutions and self-perpetuating—because hatred, unlike a fixed problem, never stops being useful. The followers believe they are fighting for their survival; they are actually providing free labour for their exploiters.

Survivors of narcissistic abuse, whether familial, professional, or political, report such similar experiences regardless of context: the disorientation of discovering the relationship was never real, the exhaustion of having given so much for so little, the slow work of rebuilding capacity for genuine connection. The narcissist, whether parent or president, takes what does not belong to them and calls it their due. Recognition of this pattern—the same theft, the same mechanisms, the same wreckage—is the first step towards refusing to be stolen from again.

The palace metaphor applies to democracies as surely as to individuals. A healthy democracy, like a healthy psyche, does not need constant external validation. It can tolerate criticism and change course when evidence demands, because its legitimacy comes from within—from the consent of the governed, not from the grandiosity of its leaders. The narcissistic leader offers the maze: exciting, disorienting, dependent on his navigation. Democracy offers the palace: quieter, stabler, built by and for all who dwell within it. The choice between them—at the ballot box and in civic participation—is the choice between borrowed grandiosity and earned dignity, between the excitement of destruction and the slower work of building. The choice, ultimately, is ours.