Introduction: The Theft of Certainty

Joelle Tamraz was barely past twenty when she travelled to India in search of spiritual enlightenment. In Rishikesh, the home of yoga, she met an alluring older man who offered to teach her a secret practice. He was thirty-three years her senior, charismatic, seemingly wise. What followed was eighteen years of psychological captivity. “I was controlled emotionally and financially,” she writes in her memoir The Secret Practice. 1209 Despite holding a Harvard degree and later an MBA from INSEAD, despite working corporate jobs to support his lifestyle, despite eventually owning a yoga studio—she could not see what was happening to her. “He told me my perceptions were wrong, that I was spiritually immature, that my doubts were ego. And the thing is—I believed him. For eighteen years, I believed him. I had stopped trusting my own mind.”

This disorientation—the gradual erosion of confidence in one’s own perceptions and memories—represents Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. ’s most devastating effect. Named after the 1944 film “Gaslight” (in which a husband dims gaslights while insisting the lighting has not changed, moves objects while claiming his wife moved them, and hides items while suggesting she lost them—all to convince her she is insane so he can institutionalise her and steal her inheritance), gaslighting has become recognised as a form of psychological abuse so insidious that victims often cannot identify it even as it destroys their mental health. Unlike physical abuse’s visible injuries or verbal abuse’s remembered words, gaslighting leaves no evidence except the victim’s growing confusion about what is real.

In relationships with narcissists, gaslighting serves key functions: it protects the narcissist’s grandiose self-concept (Chapter ) by reframing criticism as the victim’s distortion, and maintains control by keeping victims uncertain and dependent. The narcissist’s need to be right, to be admired, to be beyond criticism, requires that reality itself become negotiable, and the victim’s grip on reality becomes the sacrifice.

The gaslit self is not weak or foolish—it is human. Our sense of reality is more fragile than we imagine, dependent on social validation and consistency of experience. When a trusted intimate systematically undermines these foundations, anyone can lose their certainty. Recovery requires not just leaving the abusive relationship but rebuilding the fundamental capacity to trust one’s own mind—and learning to recognise when accusations lack the basic logical structure that would make them worth evaluating at all.

Gaslighting Defined: The Systematic Erosion of Reality

Origins and Evolution of the Concept

The term “gaslighting” originates from Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play “Gas Light” and its film adaptations, particularly the 1944 version starring Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer. In the story, a husband attempts to steal his wife’s inherited jewels by convincing her she is insane, enabling him to commit her to an asylum. His tactics include dimming the gaslights (while insisting they have not changed), moving objects and claiming she moved them, hiding items and suggesting she lost them, and denying her perceptions while insisting she is becoming unstable.

While the term entered popular usage only recently, the phenomenon it describes has been recognised throughout history. Clinical literature documented similar behaviours as “reality distortion” in borderline relationships, “crazy-making” in family therapy texts, and “brainwashing” in studies of coercive control. The 1970s feminist movement brought attention to domestic abuse’s psychological dimensions, recognising that some partners used reality manipulation as a weapon 546 .

The concept gained clinical legitimacy through research on intimate partner violence revealing that psychological abuse often proves more damaging than physical violence 257 . Dr Evan Stark’s work on coercive control 1172 —reframing domestic violence as a pattern of controlling behaviours akin to terrorism and hostage-taking rather than discrete violent incidents—documented how abusers use reality distortion to maintain dominance. Dr Jennifer Freyd’s betrayal trauma theory 421 (positing that remaining unaware of abuse serves social utility when the perpetrator is a caregiver upon whom one depends) explained why victims doubt their own perceptions when betrayed by trusted intimates. These frameworks provided theoretical foundation for understanding gaslighting’s mechanisms and effects.

Social media has accelerated recognition of gaslighting, where survivors share experiences and identify patterns 1203 . The hashtag #gaslighting has millions of posts describing similar tactics across different relationships, revealing gaslighting’s systematic nature rather than isolated incidents. This collective recognition has been both therapeutic (validating victims’ experiences) and potentially problematic (leading to over-diagnosis of normal disagreement as gaslighting).

Core Definition and Essential Features

Gaslighting, in clinical terms, describes systematic psychological manipulation in which the perpetrator causes the victim to question their own perceptions and memories. It differs from ordinary disagreement, misunderstanding, or even lying.

Gaslighting is a persistent pattern that goes beyond isolated incidents—a single lie or disagreement about facts does not constitute gaslighting. Rather, it involves repeated reality-distortion across multiple domains over extended time, the pattern itself evolving into pathology. While perpetrators may not consciously understand they are gaslighting, the behaviour serves strategic purpose: maintaining control, avoiding accountability, or protecting self-concept. The narcissist’s need to be right supersedes truth.

Unlike other lies or manipulations targeting specific facts, gaslighting attacks the victim’s capacity to know what is real 71 . The goal extends beyond deception about particular events to undermining the victim’s fundamental trust in their own perception and memory. This destabilisation escalates gradually: initial reality-distortions may be subtle—minor contradictions, small denials, gentle suggestions that the victim misunderstood. Over time, the contradictions grow more blatant, but by then the victim’s confidence is already eroded.

Gaslighting works most effectively when victims lack external validation. The narcissist often works to isolate victims socially, ensuring no one else can confirm the victim’s perceptions or provide reality-checking. Its power derives from the perpetrator’s relationship to the victim: we trust intimate partners, parents, or close friends to share our reality. When they systematically contradict our perceptions, we question ourselves before questioning them.

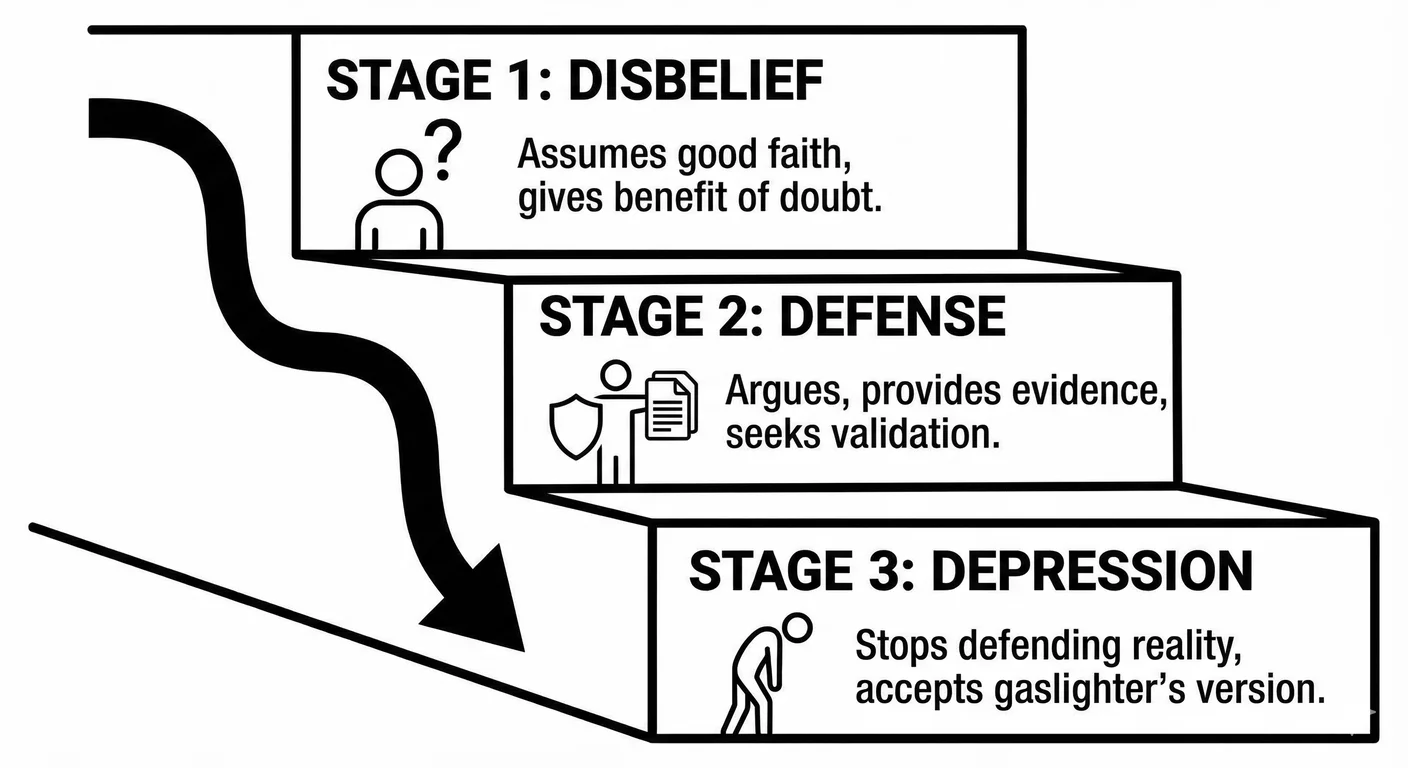

Dr Robin Stern’s ‘The Gaslight Effect’ 1184 describes three stages:

Stage 1: Disbelief. The victim recognises disagreement about reality but assumes good faith. “He says I said something I don’t remember saying, maybe I did forget?” The victim gives the gaslighter benefit of the doubt, assuming misunderstanding rather than manipulation.

Stage 2: Defence. The victim begins arguing, trying to prove their version of reality with evidence. “No, you definitely said you’d pick up the groceries—look at this text message!” The gaslighter dismisses evidence, reinterprets it, or claims the victim is being controlling or crazy for keeping “score.”

Stage 3: Depression. The victim stops defending their reality, accepting the gaslighter’s version to maintain peace. “You’re right, I must have misunderstood.” By this stage, the victim has lost confidence in their own perceptions and experiences constant anxiety about potentially “creating problems” with their faulty memory or interpretation.

Distinguishing Gaslighting from Related Phenomena

Gaslighting vs Lying: Ordinary lying conceals or distorts specific facts to avoid consequences or gain advantage. Gaslighting goes further: it causes the victim to doubt their capacity to know facts. A partner lying about an affair deceives about particular events. A partner gaslighting about an affair denies the victim’s perceptions (“You’re paranoid,” “You’re crazy,” “That never happened,” “You’re remembering wrong”), making the victim question their sanity rather than their information.

Gaslighting vs Disagreement: Healthy relationships involve genuine disagreements about perception and memory. Two people can honestly remember events differently without either gaslighting. Three features distinguish gaslighting: (1) power asymmetry, where one person consistently invalidates the other’s reality; (2) pattern persistence, where the reality-distortion is systematic rather than occasional; and (3) emotional manipulation, where gaslighting involves shaming or pathologising the victim’s perceptions.

Key Differences Between Healthy Disagreement and Gaslighting

| Healthy Disagreement | Gaslighting |

|---|---|

| Both perspectives respected | One perspective invalidated |

| ”We remember it differently" | "You’re wrong/crazy/lying” |

| Focus on resolving issue | Focus on proving victim wrong |

| Occasional pattern | Persistent, escalating pattern |

| Evidence considered | Evidence dismissed or reframed |

| Power balance maintained | Power asymmetry (one dominates) |

| Both can be partially right | Only gaslighter’s version accepted |

| Victim’s sanity not questioned | Victim labelled unstable/paranoid |

| Good faith assumed | Manipulation intended |

| Results in understanding | Results in confusion/self-doubt |

Gaslighting vs Misunderstanding: Genuine misunderstandings can be resolved through good-faith communication. Gaslighting resists resolution because the gaslighter’s goal is domination, with mutual understanding irrelevant. When victims present evidence supporting their version of reality, healthy partners acknowledge it (“Oh, you’re right, I did say that—my mistake”). Gaslighters escalate (“You’re twisting everything,” “You’re always keeping score,” “You’re trying to control me with your version of events”).

Gaslighting vs False Memory: Memory is genuinely reconstructive and fallible. People do misremember, confabulate, or experience false memories, particularly around emotional or traumatic events. Gaslighting exploits this normal memory fallibility but reveals itself through pattern: when one person consistently claims the other misremembers while insisting their own memory is perfect, when the supposed “false memories” always favour the gaslighter’s interests, when the victim’s memory proves accurate when verified externally, gaslighting is likely the cause. The nulling frame applies here too: when someone claims your memory is false, they bear the burden of demonstrating this. “Show me the evidence my memory is wrong” is a legitimate response to “You’re misremembering”, and gaslighters typically cannot provide such evidence because the victim’s memory is accurate.

Why Narcissists Gaslight

Gaslighting serves specific functions in narcissistic psychology, making it a nearly inevitable feature of narcissistic relationships.

The narcissist’s grandiose self-concept (Chapter ) finds being wrong intolerable. When reality contradicts their preferred narrative—they made a promise they did not keep, they said something hurtful, they failed at something—reality must be wrong. Gaslighting reframes criticism or contradiction as the victim’s distortion rather than the narcissist’s error. This protects the narcissist from shame, which they experience as devastating attack. Rather than tolerating the discomfort of being wrong or apologising, they deflect by making the victim wrong instead. “I didn’t do that hurtful thing; you misunderstood my intentions” preserves the narcissist’s self-concept while placing blame on the victim.

Beyond protecting self-image, gaslighting maintains control. A victim who trusts their own perceptions might leave; a victim who doubts their perceptions stays, constantly seeking the narcissist’s validation of reality. Gaslighting creates psychological dependence: the victim needs the narcissist to tell them what is real. This ensures continued Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. —when victims doubt themselves, they spend energy analysing their own potential flaws rather than evaluating the narcissist’s behaviour. The gaslit victim asks “What’s wrong with me?” instead of “What’s wrong with this relationship?”

Gaslighting also makes the narcissist’s projections stick. Narcissists project their own unacceptable traits onto others (see Chapter on defence mechanisms). When caught lying, they accuse victims of lying. When behaving cruelly, they claim victims are too sensitive. By undermining the victim’s confidence in their own assessment, gaslighting prevents victims from recognising these projections for what they are. At its most fundamental, controlling what is real represents ultimate dominance. Physical violence proves you can hurt someone; reality distortion proves you can make them question their sanity. This exemplifies the narcissist’s fantasy of omnipotence realised—controlling perception itself, extending beyond behaviour.

Techniques and Tactics: The Arsenal of Reality Distortion

The Lexicon of Gaslighting

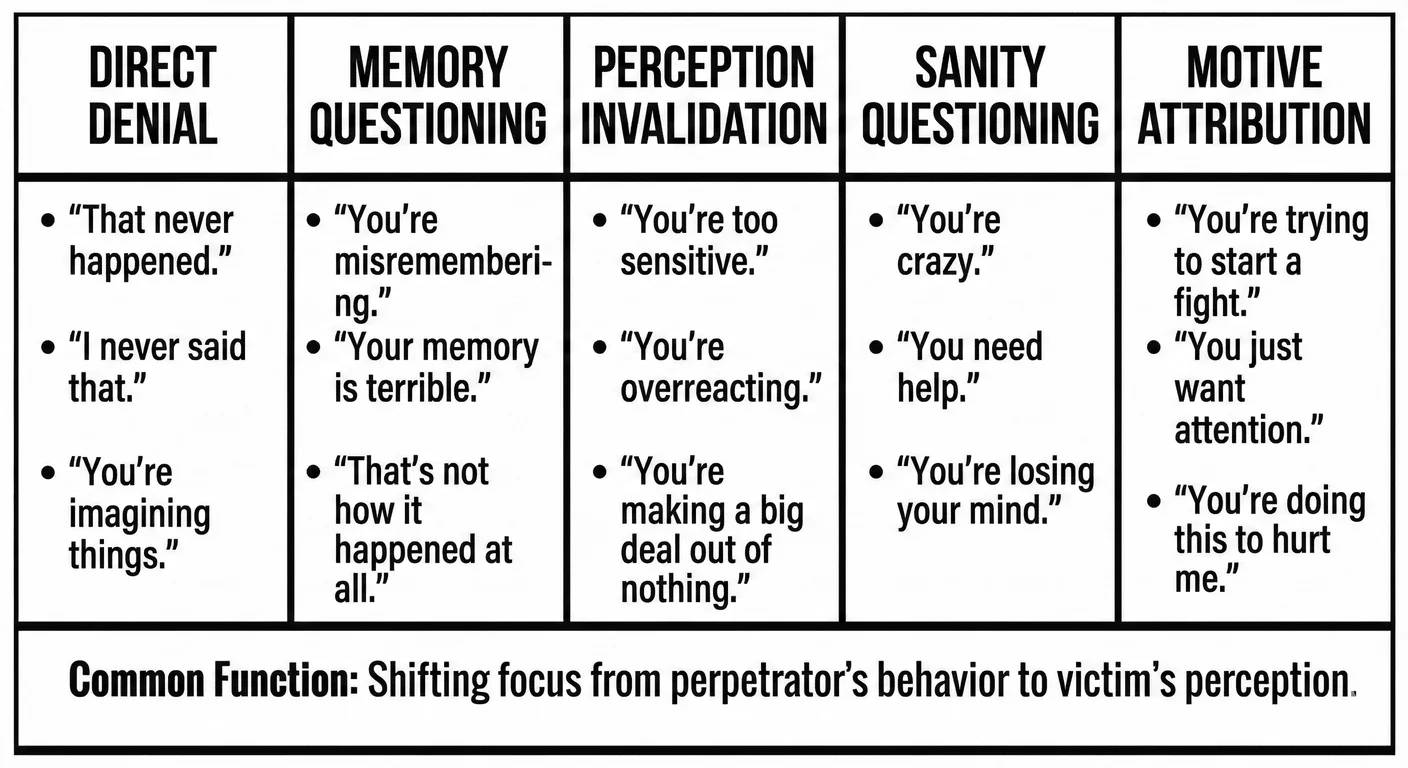

Dr Stephanie Sarkis’s ‘Gaslighting’ 1087 catalogues common gaslighting statements:

Direct Denial:

-

“That never happened.”

-

“You’re making things up.”

-

“I never said that.”

-

“You’re imagining things.”

-

“That’s not what happened.”

Memory Questioning:

-

“You’re misremembering.”

-

“You always forget things.”

-

“Your memory is terrible.”

-

“Are you sure that’s how it happened?”

-

“You’re confused.”

Perception Invalidation:

-

“You’re too sensitive.”

-

“You’re overreacting.”

-

“You’re blowing this out of proportion.”

-

“You’re being dramatic.”

-

“You’re reading too much into things.”

Sanity Questioning:

-

“You’re crazy.”

-

“You’re paranoid.”

-

“You need help.”

-

“You’re losing it.”

-

“Are you off your medication?”

Motive Attribution:

-

“You’re just trying to start a fight.”

-

“You always create drama.”

-

“You’re being manipulative.”

-

“You’re trying to control me.”

-

“You enjoy making me feel bad.”

These phrases share a common function: shifting focus from the narcissist’s behaviour to the victim’s perception. Instead of addressing whether the behaviour occurred or was harmful, the gaslighter makes the victim’s reaction the problem.

Memory Manipulation Techniques

Gaslighters systematically undermine victims’ confidence in their own memory through several interlocking tactics. When confronted with their words or actions, the gaslighter denies them completely while projecting absolute certainty: “I would never say something like that. You’re wrong.” The confidence matters critically—it makes the victim doubt their memory because the gaslighter seems so sure. Beyond simple denial, the gaslighter often provides a detailed alternative account, inverting who said or did what. “No, you’re the one who said we shouldn’t go to your mother’s. I wanted to go, but you insisted we stay home.” The specificity makes the false version seem credible.

Repetition compounds the damage. The gaslighter repeats their false version consistently while the victim’s memory naturally becomes less certain over time. Human memory is reconstructive; repeated exposure to an alternative version can actually contaminate genuine memory. 759 Elizabeth Loftus’s misinformation effect research demonstrates that misleading information can overwrite original memory of events—gaslighters exploit this normal memory malleability through confident, repeated denial of the victim’s accurate recollections. After hearing the gaslighter’s version multiple times, victims genuinely become unsure what happened.

The gaslighter’s own memory proves conveniently selective: no recollection of events that reflect poorly on them, but perfect recall of the victim’s alleged transgressions. Promises forgotten, hurtful statements unremembered, agreements vanished—yet the victim’s mistakes are cataloged in detail. When victims present evidence (texts, emails, recordings), gaslighters dismiss it: “That’s out of context,” “You’re misinterpreting it,” “You must have edited that,” “Why are you keeping score?” The message: even documented reality is suspect if it contradicts the narcissist’s version.

The gaslighter also projects memory problems onto the victim while claiming perfect recall themselves. “You always forget things. I have to remember everything for both of us.” A narrative forms in which the victim is an unreliable narrator of their own life.

Perception Manipulation Strategies

Beyond memory, gaslighters target the victim’s trust in their own perceptions and interpretations. The victim’s emotional responses are consistently labelled as wrong or pathological: if the victim is hurt, they are “too sensitive”; if angry, they are “overreacting”; if sad, they are “being dramatic.” Over time, victims learn to distrust their emotional responses, constantly second-guessing whether their feelings are legitimate.

When behaviour causes harm, the gaslighter insists their intentions determine meaning, not impact. “I didn’t mean it that way, so you shouldn’t be upset.” The victim’s experience of harm becomes invalid because the gaslighter claims beneficent motives. Alternatively, the gaslighter reframes events by adding context that supposedly explains why the victim’s interpretation is wrong. “Yes, I yelled, but only because you wouldn’t listen.” “I ignored you, but you had been nagging me all day.” The behaviour is admitted but recontextualised so that it becomes the victim’s fault.

When victims express upset, the gaslighter focuses on their tone rather than content: “I can’t have a conversation when you’re being so emotional,” “Your voice is too loud,” “You’re being hysterical.” This shifts attention from the substantive issue to the victim’s supposedly inappropriate expression of it. The gaslighter may also compare the victim’s concerns to worse scenarios to make them seem trivial: “Other people have real problems. You’re complaining about nothing.” “At least I don’t hit you.” “You should be grateful—most people would have left you by now.” This trains victims to minimise their own legitimate concerns.

Sophisticated gaslighters weaponise psychological and therapeutic terminology to pathologise victims’ legitimate concerns—a tactic particularly effective against victims in therapy who may internalise these diagnostic labels. “You’re projecting,” “You’re triggered,” “You have boundary issues,” “That’s your childhood trauma talking.” Victims, often in therapy themselves, may believe these diagnostic labels, doubting their perceptions further.

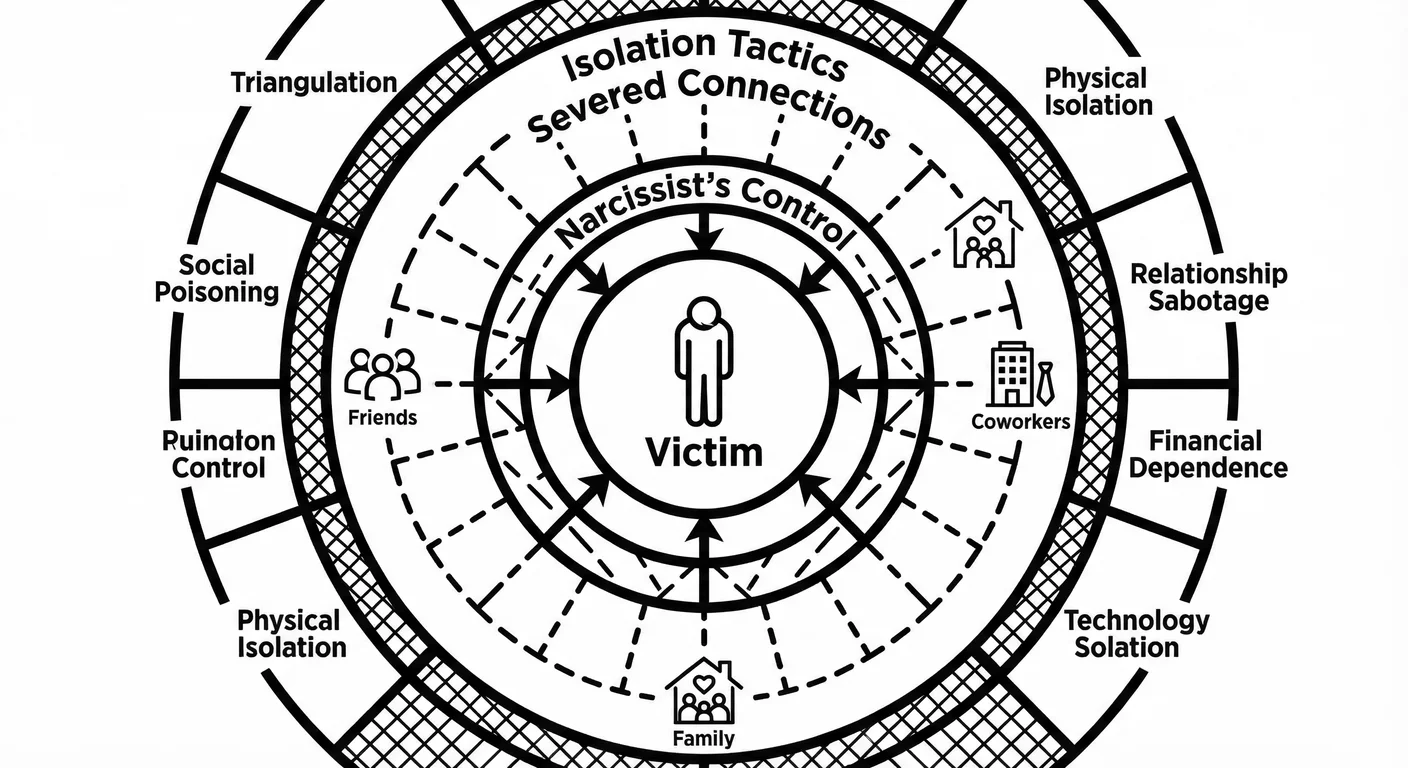

Isolation Tactics

Gaslighting works most effectively when victims lack external reality-checking. Narcissists systematically isolate victims through multiple channels.

Through triangulation, the narcissist brings third parties into conflicts, claiming others agree with the narcissist’s version: “Everyone thinks you’re crazy,” “Your mother agrees with me,” “I talked to your friends and they said you’re the problem.” Often these claims are fabricated, but they prevent victims from seeking validation from those people. The narcissist may also poison social relationships directly, telling others that the victim is unstable or unreliable, preemptively discrediting anything the victim might say. If the victim does reach out for support, they encounter scepticism because the narcissist has already shaped others’ perceptions.

Over time, the narcissist creates conflict between the victim and their support system through lies or manufactured crises that make the victim appear difficult. Friends and family distance themselves, leaving the victim dependent on the narcissist for reality validation. The narcissist may monitor or control the victim’s phone, email, or social media, limiting their ability to communicate with others without the narcissist’s knowledge. This prevents the victim from describing the abuse or seeking outside perspective.

Economic control further limits the victim’s ability to leave or maintain independent relationships. Without financial resources, victims cannot easily meet friends, cannot afford therapy, cannot access resources that might help them recognise the abuse. In extreme cases, the narcissist may relocate the victim away from their support system, prevent them from working, or create situations where the victim rarely interacts with anyone else. This complete isolation makes the narcissist’s version of reality the only version the victim encounters.

Identity-Based Gaslighting: For LGBTQ+ victims, isolation tactics exploit additional vulnerabilities. Eldar, a thirty-four-year-old gay man, describes how his partner weaponised his identity: “When I came out in my twenties, my family cut me off. My partner knew I had no family support. He used that constantly—‘Who else would love you? Your family doesn’t even accept you.’ When I got upset about his behaviour, he’d say I was being ‘too emotional, like all gay men,’ reinforcing stereotypes I’d internalised. He told people I was ‘struggling with internalised homophobia’ when actually I was struggling with his abuse. The LGBT community was my chosen family, but he isolated me from them by creating drama, then telling mutual friends I was the unstable one. I was terrified to speak up because if I lost that community, I’d have absolutely no one.”

Dr Ilan Meyer’s minority stress theory 857 —distinguishing distal stressors (external experiences like discrimination) from proximal stressors (internal experiences like internalised homophobia)—explains how LGBTQ+ individuals face additional stressors that create psychological vulnerability. Narcissistic partners exploit these vulnerabilities, using societal marginalisation as an isolation tool. Identity-based gaslighting includes denying that discrimination occurred (“You’re being paranoid, not everything is homophobia”), using identity as an explanation for problems (“You’re just sensitive because of your identity issues”), threatening outing or weaponising closet status, claiming the victim’s identity makes them inherently unstable, and isolating them from the LGBTQ+ community where they might find validation and support.

The Double Bind

Double binds create situations where the victim cannot win regardless of their choice:

If the victim stays calm when upset, the narcissist claims they do not really care. If the victim shows emotion, they are too emotional. If the victim provides evidence, they are keeping score. If they do not provide evidence, they have no proof. If the victim leaves, they are abandoning the relationship. If they stay, they are enabling dysfunction.

These double binds create psychological paralysis. Every option leads to criticism, so victims freeze, unable to trust their judgement about appropriate responses. The narcissist’s inconsistent standards ensure the victim is always wrong, always off-balance, always seeking the narcissist’s validation that the correct choice was made.

Psychological Impact: The Destruction of the Self

Cognitive Effects

Gaslighting produces measurable changes in cognition that can persist long after the abusive relationship ends.

Victims lose confidence in their judgement, experiencing anxiety about even minor decisions. Should they take this job? Is this friendship healthy? Should they wear this outfit? Decisions that others make automatically require extensive deliberation because victims no longer trust their own assessment. Research on decision-making under uncertainty demonstrates that effective choices require confidence in one’s judgement. 626 Gaslighting inverts the normal pattern (where people are often overconfident): it systematically destroys confidence in judgement that is actually accurate, leaving victims unable to trust the decision-making apparatus essential for autonomy. The internal monologue shifts from “What do I think?” to “What would someone else think?” or “What’s the right answer?”

This uncertainty extends to memory itself. Victims report difficulty trusting their memories even about non-abuse-related events. “Did I lock the door? Did I turn off the stove? What did I eat for breakfast?” The gaslighter’s systematic denial creates generalised uncertainty about recall. Some victims develop compulsive checking behaviours or excessive documentation to compensate for perceived memory unreliability. Psychologists distinguish between memory for experienced events versus imagined or dreamed events, a capacity called reality monitoring 614 . Gaslighting damages this capacity. Victims genuinely become unsure whether they experienced something, dreamed it, imagined it, or heard about it. The boundaries between reality and fantasy blur.

Attempting to defend their reality, victims replay interactions obsessively, analysing every word and gesture for meaning. They record conversations, save messages, document events, trying to build evidence that will withstand the gaslighter’s denial. This hypervigilance is exhausting and paradoxically reinforces self-doubt: “Why do I need so much evidence if my perceptions were reliable?” Underlying everything is deep cognitive dissonance between contradictory beliefs: “This person loves me” versus “This person is deliberately harming me.” “I’m intelligent and competent” versus “I can’t trust my own mind.” “This behaviour is wrong” versus “Maybe I’m overreacting.” The psychological tension of maintaining contradictory beliefs creates anxiety and exhaustion. 387 Gaslighting victims typically resolve this dissonance by denying the abuse (“maybe I’m overreacting”) rather than questioning love for the abuser, because abandoning the relationship feels more threatening than doubting one’s own sanity.

Emotional Consequences

Gaslighting devastates emotionally, and survivors often report that the psychological impact rivals or exceeds what physical abuse survivors describe.

The defining emotional consequence is pervasive uncertainty about one’s own perceptions and worth. Victims constantly question whether they are seeing things clearly, whether their emotional responses are appropriate, whether they are the problem in every situation. This self-doubt infiltrates all aspects of life. Living in an environment where reality is unstable creates constant anxiety. Victims develop anticipatory stress, worrying about saying or doing something that will be twisted or used against them. Sleep disturbance, panic attacks, and generalised anxiety disorder are common 1172 .

As victims lose trust in their perceptions and fail repeatedly to resolve conflict through communication (because the gaslighter has no interest in resolution), depression develops. The Learned Helplessness Learned Helplessness A psychological state where repeated exposure to uncontrollable events leads to passive acceptance and belief that escape is impossible. paradigm 1115 applies: when efforts to change situations prove futile, depression follows. Victims feel trapped in relationships where someone else controls reality itself. Gaslighting’s rhetoric consistently places blame on victims: they are too sensitive, they misremember, they create drama, they are the problem. Over time, victims internalise these messages. They feel ashamed of their “excessive” emotional reactions, their “faulty” memory, their “inability” to communicate properly. This shame prevents disclosure and help-seeking.

Eventually, many victims stop feeling much at all. After having emotions consistently invalidated, they suppress emotional responses preemptively. This numbing protects against invalidation’s pain but leaves victims feeling empty, disconnected from themselves and others. The clinical presentation can resemble depression but reflects something more fundamental: the abandonment of one’s own emotional experience as a survival strategy. Victims also grieve—for the loss of themselves, the person they were before gaslighting eroded their self-concept. They mourn the relationship they thought they had (which turned out to be illusion), the time invested in dysfunction, the opportunities forgone while trapped in abuse. This grief is complicated because outsiders often fail to understand what was lost.

Nadia, a forty-one-year-old architect, describes the aftermath eighteen months after leaving her husband. “I used to make decisions for a living. Site plans, structural choices, client presentations—I was good at it. Now I stand in the supermarket for twenty minutes trying to choose between two brands of pasta. I’m terrified of choosing wrong.” She pauses. “The thing is, I know it’s pasta. I know it doesn’t matter. But somewhere in my head, his voice is asking what kind of idiot can’t even buy groceries properly. And I can’t tell anymore if that’s him or if that’s me.” She still checks her phone compulsively, though he hasn’t contacted her in months. “I dream about arguments we had. I wake up and I’m not sure if they really happened or if I invented them. My therapist says that’s normal, that gaslighting does that. But how would I know if my therapist is right?” She got a promotion last month. Her boss said she’d earned it. She spent the weekend making lists of reasons the decision might be reversed. “I keep thinking I should feel better by now. Eighteen months. I left. I won, or whatever. So why am I still—” She stops, looks at her hands. “Sorry. I don’t know where I was going with that.”

Identity Disruption

Gaslighting’s deepest impact is on identity itself. It attacks the foundation of identity: the ability to know oneself. Victims who once had a clear sense of their values and boundaries find these dissolving. “What do I actually think about this?” becomes unanswerable because the gaslighter’s voice has colonised their internal dialogue.

Developmental psychology establishes that healthy identity forms through integration of self-experience across time and contexts 360 . Gaslighting disrupts this integration. If your memory is unreliable and your perceptions questionable, what remains of a consistent self-concept? The victim becomes a collection of doubt rather than an integrated person. In healthy development, people learn to articulate their needs and boundaries. Gaslighting teaches that one’s voice is invalid, that expressing needs invites punishment or mockery. Victims learn to silence themselves preemptively, losing access to their own desires and opinions. The question “What do I want?” becomes terrifying because any answer might be wrong.

Gaslighting systematically violates psychological boundaries. The gaslighter’s version of reality must supersede the victim’s experience. Over time, victims lose the sense of where they end and others begin. They have difficulty maintaining boundaries in all relationships because the fundamental right to one’s own perceptions has been violated. Agency—the capacity to act as a causal agent in one’s life—requires trust in one’s judgement and perceptions. Gaslighting destroys this trust. Victims feel like passive recipients of reality rather than active constructors of meaning. Life happens to them; they do not make choices within it. This agency loss persists even after leaving the abusive relationship.

Interpersonal Impact

Gaslighting’s effects extend beyond the abusive relationship to all interpersonal functioning.

Having had trust so thoroughly betrayed, victims struggle to trust anyone. They become hypervigilant for signs of manipulation, questioning whether others’ words match their intentions. Healthy relationships require some baseline trust; gaslighting makes this feel impossibly risky. The shame of having been manipulated, combined with fear that others will not believe their experience, keeps victims isolated. They withdraw socially, believing they cannot trust their judgement about people and fearing others will think them crazy if they disclose the abuse.

Paradoxically, gaslighting victims sometimes enter new relationships with similar dynamics. Accustomed to having their reality questioned, they may gravitate towards partners who seem certain, not recognising controlling behaviour until deep into the relationship. The familiar pattern of self-doubt can feel perversely comfortable. Some victims overcorrect, becoming rigidly certain about their perceptions and resistant to any feedback or alternative perspective. Having had their reality violated, they become defensive about their version of events, potentially creating conflict in healthy relationships where genuine disagreement occurs.

Gaslighting trains victims that communication is unsafe, that anything they say can be twisted or used against them. They may become extremely guarded in all communications, sharing little, or conversely, over-explain everything defensively, anticipating disbelief.

Physical Health Consequences

The chronic stress of gaslighting produces measurable physical health effects.

Living under constant reality threat activates chronic stress response. Elevated cortisol, dysregulated HPA axis, impaired immune function, cardiovascular strain—the physical correlates of chronic psychological stress all appear in gaslighting victims 833 . Victims often develop physical symptoms without clear medical cause: chronic pain, gastrointestinal problems, headaches, fatigue 1272 . These represent somatisation of psychological distress, the body expressing what the mind cannot safely articulate.

The hypervigilance and anxiety produce severe sleep disturbance. Victims report difficulty falling asleep (mind racing through interactions, trying to understand what happened), frequent waking, nightmares featuring confrontations or reality confusion, and unrefreshing sleep leaving them exhausted. Some victims turn to alcohol or prescription medications to manage the anxiety and psychological pain. The gaslighter may then use this substance use as evidence that the victim is unstable, creating a vicious cycle.

Recovery Challenges: Why Escape Is So Difficult

The Recognition Problem

Victims often do not recognise they are being gaslit. Gaslighting escalates gradually—what begins as minor disagreements about facts progresses slowly to wholesale reality denial. Like the proverbial frog in slowly heating water (the metaphor is scientifically inaccurate but culturally resonant), victims adapt to each incremental increase in reality distortion without recognising the overall pattern. By the time the gaslighting is severe, the victim’s baseline has shifted so far that extreme manipulation seems normal.

Victims typically love or loved the gaslighter. This emotional attachment makes it difficult to accept that someone they care about is deliberately harming them. Victims typically resolve the Cognitive Dissonance Cognitive Dissonance The psychological discomfort of holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously—common in abuse when the person harming you is also someone you love. between “This person loves me” and “This person is systematically destroying my sanity” by denying the second rather than questioning the first. Good days reinforce this denial. Abusive relationships are not constantly abusive. Good days exist, even good weeks, when the gaslighter is charming, affectionate, or reasonable. These periods of intermittent reinforcement (see Chapter ) are powerfully addictive 340 . They make victims question whether the abuse is real: “Maybe I was imagining it. Maybe it’s not that bad. Look how wonderful things are right now.”

Until recently, gaslighting was not widely discussed in public discourse. Victims lacked language to describe their experience. Without the framework to understand what is happening, they blame themselves. “I must actually have bad memory. I must be too sensitive. I must create drama.” They accept the gaslighter’s narrative because they have no alternative explanation. Many gaslighting victims are highly competent, successful people in other domains. Accepting they are being manipulated becomes harder: “I have a PhD—how could I be fooled like this?” “I manage teams at work—why can’t I handle this relationship?” The assumption that intelligence or competence protects against manipulation actually increases vulnerability by preventing recognition.

The Leaving Problem

Even after recognising gaslighting, leaving proves extraordinarily difficult.

Many narcissists establish financial control early. The victim may be unable to work, lack access to money, have no credit in their own name, or face destitution if they leave. Economic abuse keeps victims trapped as effectively as locked doors 8 . When children are involved, victims fear losing custody, worry about co-parenting with a narcissist, or stay to protect children from the narcissist’s full attention. The narcissist exploits this, using children as leverage: “Leave and you’ll never see them again,” “I’ll tell everyone you’re an unfit parent,” “The kids will hate you for breaking up the family.”

If the narcissist has successfully isolated the victim or poisoned their reputation, support systems may pressure the victim to stay: “Marriage takes work,” “You’re giving up too easily,” “What did you do to cause this?” Family and religious communities sometimes prioritise relationship preservation over safety. Even recognising gaslighting intellectually, victims struggle with persistent doubt. “Maybe I am too sensitive. Maybe I do have bad memory. Maybe everyone experiences this in relationships and I’m just weak.” The gaslighter’s voice has become internalised; leaving means trusting one’s own judgement, which gaslighting specifically destroyed.

Narcissists often escalate abuse when victims attempt to leave. Threats, stalking, financial sabotage, custody battles, character assassination—the narcissist cannot tolerate the Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. of being left. Victims rationally fear what will happen if they try to escape. The intermittent reinforcement of gaslighting creates powerful trauma bonds (see Chapter on borderline-narcissist dynamics). The biochemistry of fear mixed with love, of hope alternating with despair, creates addiction-like attachment. The victim may feel physically unable to leave despite cognitively knowing they should. 340 Dutton and Painter’s empirical test of traumatic bonding theory identified two necessary ingredients: power imbalance and intermittent abuse—explaining why victims struggle to leave despite recognising abuse.

Victims hope the gaslighter will change, especially if the gaslighter occasionally acknowledges problems or promises improvement. This hope keeps victims trapped through endless cycles of abuse-apology-honeymoon-abuse. The narcissist skilfully manages this hope, providing just enough change to maintain it while never genuinely transforming.

The Rebuilding Problem

After leaving, recovery faces multiple obstacles.

Victims often lack a safe environment to process their experience. If the narcissist has social connections with the victim’s friends or family, nowhere feels secure. Disclosure risks getting back to the narcissist or encountering disbelief from those who saw the narcissist’s public persona. The narcissist does not disappear after separation. Stalking, harassing texts, Flying Monkeys Flying Monkeys People recruited by a narcissist to do their bidding, spread their narrative, gather information, or pressure their target, often unknowingly participating in abuse. recruited to check on the victim or pressure reconciliation, custody battles weaponising children, financial attacks— Post-Separation Abuse Post-Separation Abuse Abuse that continues or intensifies after the victim leaves the relationship. Narcissists often escalate control tactics, stalking, legal abuse, financial manipulation, and harassment when they lose direct access to their victim. can exceed the relationship’s abuse. Victims never get space to heal because the attacks continue.

Free from the gaslighter’s active manipulation, victims often turn that critical voice inward. “Why did I stay so long? Why didn’t I see it? What’s wrong with me that I attracted this?” They ruminate on the relationship, trying to make sense of what happened, often blaming themselves for the abuse they suffered. Finding effective therapy requires trusting someone with vulnerable information, exactly what gaslighting taught was dangerous. Many victims have difficulty engaging in therapy, fearing the therapist will not believe them, will blame them, or will be manipulated by the narcissist if they contact the therapist.

Having lost their sense of self during gaslighting, victims face the task of rebuilding identity without clear foundation. Who are they outside the relationship? What do they like? What are their values? These questions that most adults can answer easily become existentially difficult for gaslighting survivors. Economic abuse often leaves victims financially ruined: destroyed credit, debt, no work history, no assets. Rebuilding financial security while also recovering psychologically proves overwhelming. Practical survival needs compete with healing needs for limited resources.

The Social Understanding Gap

Others’ failure to understand often frustrates recovery most.

Gaslighting leaves no visible scars. Well-meaning friends and family struggle to understand why the victim is so impacted. “He just lied sometimes, why are you this upset?” Psychological abuse’s invisibility makes it easy for others to minimise. The narcissist typically maintains a charming public persona. When victims disclose abuse, others struggle to reconcile this with the person they know: “That doesn’t sound like him. Are you sure you’re not misunderstanding?” This disbelief replicates the gaslighting dynamic, making disclosure traumatising.

Society often blames victims: “Why did you stay?” “Why didn’t you leave sooner?” “What did you do to make him act that way?” These questions, while sometimes well-intentioned, place responsibility on the victim rather than the abuser. After leaving, victims face pressure to “get over it” and “move on with your life.” Friends grow weary of hearing about the relationship. But gaslighting’s damage runs deeper than simple breakup recovery. Victims need time to rebuild fundamental capacity to trust their own mind: a process that can take years.

Complex PTSD: The Clinical Reality of Gaslighting Trauma

From PTSD to Complex PTSD

Traditional post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was conceptualised around single-event or time-limited traumas: combat, assault, accidents, disasters. The symptoms—intrusive memories, avoidance, hyperarousal, negative alterations in mood and cognition—describe responses to circumscribed traumatic events 34 .

Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) A trauma disorder resulting from prolonged, repeated trauma, characterised by PTSD symptoms plus difficulties with emotional regulation, self-perception, and relationships. (C-PTSD), proposed by Dr Judith Herman 546 and later included in ICD-11, describes trauma resulting from prolonged, repeated exposure to interpersonal trauma from which escape is difficult or impossible. The classic examples include childhood abuse, domestic violence, and human trafficking—situations characterised by prolonged duration, interpersonal nature, and constraint.

Gaslighting-based narcissistic abuse fits the C-PTSD framework on every dimension. Gaslighting occurs over months or years, not as single incident—the cumulative effect of sustained reality distortion produces trauma distinct from one-time events. The trauma occurs within an intimate relationship, the context where humans are most psychologically vulnerable. Betrayal by trusted partner adds layers of damage beyond the gaslighting itself.

Whether through practical barriers—financial dependence, children—or psychological barriers such as trauma bonding and self-doubt, victims experience themselves as unable to escape. This sense of entrapment is itself traumatising. Unlike PTSD from discrete events, C-PTSD involves fundamental disruption of identity and relationship capacity. The self-concept, not just memory of specific events, becomes traumatised.

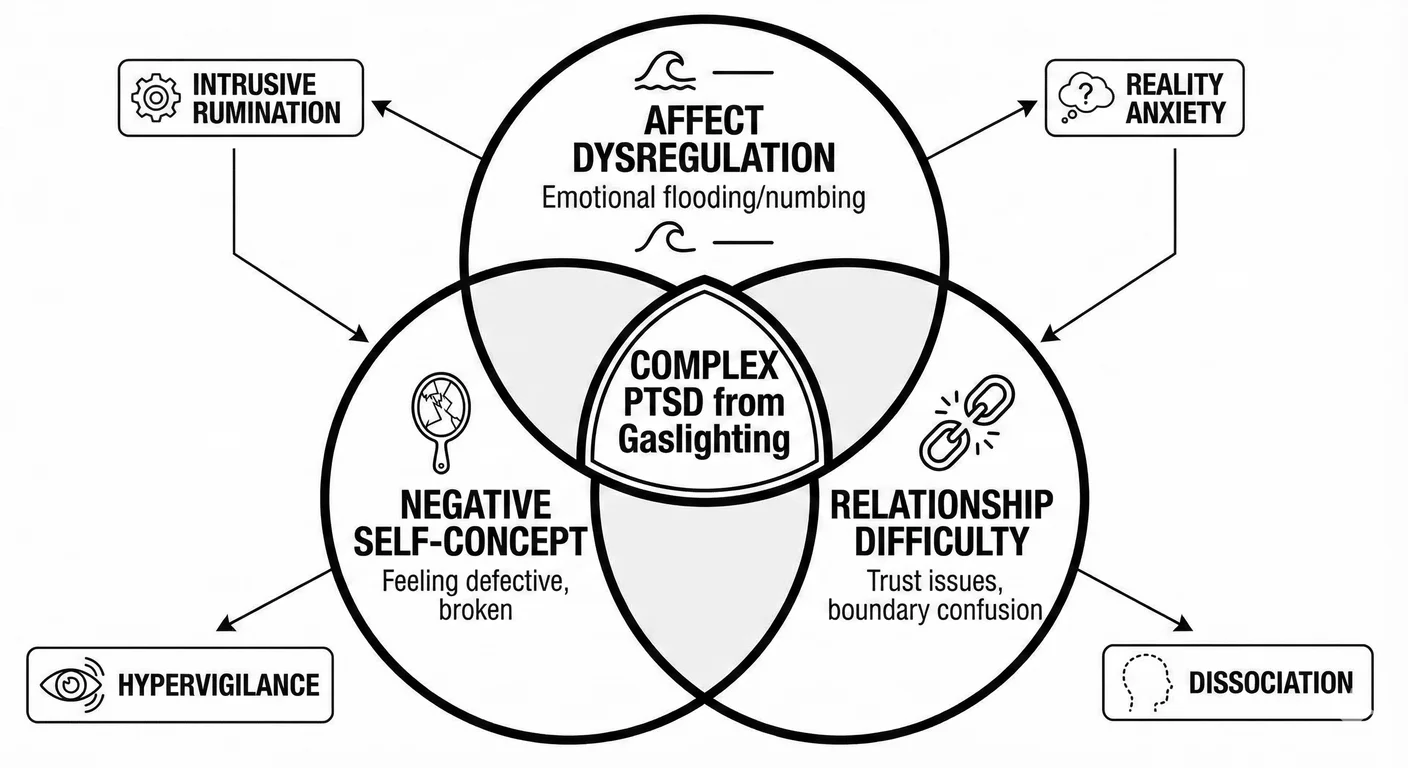

C-PTSD Symptoms in Gaslighting Survivors

Three symptom clusters beyond PTSD’s core features manifest clearly in gaslighting survivors:

Disturbances in Self-Organisation

Gaslighting survivors show difficulty managing emotional responses. They may experience emotional numbness alternating with emotional flooding. Simple triggers can produce disproportionate reactions because they access the accumulated trauma. The victim who breaks down crying when partner says “You’re being too sensitive” is not overreacting to those words but responding to hundreds of similar dismissals.

The emotional dysregulation reflects disrupted affect regulation capacity. Healthy emotional regulation develops through caregiver attunement and validation. 1099 Through “affective synchrony,” attuned caregivers intuitively match infants’ shifting autonomic arousal states, forming the basis for self-regulation capacity. Gaslighting provides the opposite: systematic emotional invalidation, destroying this foundational capacity. The message “Your feelings are wrong” internalised over time destroys the capacity to trust emotional signals, producing dysregulation.

Gaslighting survivors also develop deeply negative views of themselves: defective, flawed, crazy, broken, unlovable. These are not just low self-esteem but core identity disruptions. The victim’s sense of basic self-worth has been attacked repeatedly through the gaslighting process. This negative self-concept persists after leaving the relationship because it is not just about the relationship—it is about fundamental capacity to perceive reality accurately. If you cannot trust your own mind, what value do you have as a person? This existential-level self-condemnation distinguishes C-PTSD from simpler self-esteem issues.

All interpersonal relationships become challenging. Trust, appropriate boundaries, effective communication, conflict resolution—capacities required for healthy relationships—have been damaged by the gaslighting experience. Survivors struggle with intimacy (fearing betrayal) and distance (fearing abandonment), often recreating unstable relationship patterns.

Owen, thirty-six, left his partner three years ago. He still attends a support group. “I thought once I got out, I’d be fine. Smart guy, good job, supportive friends. I’d just… recover.” He shakes his head. “Last month my girlfriend said ‘You seem distant today’ and I had a panic attack. Not anxiety—full panic, couldn’t breathe, had to leave the room. Because that’s how it started with her. ‘You seem distant.’ Then ‘You’re always distant.’ Then ‘Everyone thinks you’re cold.’ Then I was apologising for being a terrible partner while she was sleeping with my best friend.” He’s been in therapy for two years. “My therapist calls it complex PTSD. I don’t know what to call it. I can’t tell when I’m overreacting or when I’m finally reacting appropriately. Someone criticises my work and I either feel nothing—just blank—or I want to quit on the spot. There’s no middle.” His girlfriend now is kind, patient. He tests her constantly, without meaning to. Picks fights to see if she’ll twist them. Asks the same question different ways to check if her story changes. “I hate that I do it. She asked me last week why I don’t trust her and I couldn’t explain. I do trust her. I think I do. I just can’t stop checking.” He’s quiet for a moment. “Three years out and I’m still like this. I don’t know when that’s supposed to change.”

Re-experiencing and Avoidance

Gaslighting survivors show specific re-experiencing patterns. Rather than flashbacks to specific events, survivors experience obsessive replay of interactions, analysing them endlessly for meaning. “What did I do wrong? How did this happen? Why didn’t I see it?” This rumination is not productive problem-solving but compulsive repetition attempting to make sense of nonsensical abuse.

Phrases, tones of voice, situations that recall gaslighting produce intense reactions 1001 . Someone saying “You’re too sensitive” in benign context can trigger full trauma response. The survivor’s nervous system has learned these phrases signal danger, producing automatic defensive activation. Survivors may avoid people, places, conversations, or situations that remind them of the gaslighting. This can become pervasive, limiting life severely. Avoiding all conflict means avoiding healthy relationships. Avoiding all criticism means avoiding growth opportunities. The protective avoidance becomes prison.

Hypervigilance and Altered Perception

Survivors remain hypervigilant for signs of manipulation or reality distortion. They analyse others’ words for hidden meanings, watch for inconsistencies, test people’s trustworthiness. This exhausting vigilance reflects learned adaptation to an environment where trust was dangerous. A distinctive feature of gaslighting trauma is persistent anxiety about perceiving reality accurately. Survivors constantly question their perceptions, seeking external validation, fearing they are misunderstanding situations. This reality anxiety can be more disabling than the specific PTSD symptoms.

The normal stress response becomes either under-reactive—numbing, Dissociation Dissociation A psychological disconnection from one's thoughts, feelings, surroundings, or sense of identity—a common trauma response to overwhelming narcissistic abuse. —or over-reactive, manifesting as panic or rage, with little middle ground. Survivors struggle with proportional responses because the gaslighting conditioned them to either suppress reactions completely or lose control when suppression fails.

Neurobiological Impact

Prolonged gaslighting stress produces measurable brain changes.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates stress response, becomes dysregulated through chronic activation. Cortisol patterns become abnormal—either chronically elevated or paradoxically blunted. This affects mood, memory, immune function, and physical health. 833 This neurobiological evidence shows gaslighting produces measurable brain and body changes beyond psychological symptoms.

Chronic stress impairs prefrontal cortex function, the brain region responsible for executive function, decision-making, and emotional regulation. Neuroimaging studies of trauma survivors show reduced prefrontal activity and volume. 155 Gaslighting survivors’ difficulty with decisions and emotional control follows from this damage—the brain structures supporting these functions have been physically altered by chronic stress. Meanwhile, the amygdala, processing threat and fear, becomes overactive and enlarged in trauma. Hypervigilance and exaggerated startle responses appear in survivors. Benign stimuli trigger threat responses because the amygdala has learned to detect danger everywhere 1026 .

The hippocampus, essential for memory formation and contextualising memories, shows reduced volume in chronic trauma. The memory difficulties that gaslighting already caused psychologically may reflect physical damage: the brain structure supporting memory has been damaged by chronic stress 155 . The brain’s default mode network, active during rest and self-reflection, also shows altered functioning in complex trauma 709 . This network processes self-referential thinking and identity. Its disruption may underlie the identity fragmentation and negative self-concept in gaslighting survivors.

dissociation

as Survival Strategy

Many gaslighting survivors develop dissociative symptoms.

Depersonalisation manifests as feeling like an observer of one’s own life, watching from outside, going through the motions without genuine participation. This protects against the pain of reality distortion by creating psychological distance from experience. Derealisation—experiencing the world as unreal, dreamlike, or distorted—also appears frequently. When reality has been systematically questioned, reality itself becomes uncertain. Derealisation exemplifies the psyche’s adaptation to this uncertainty.

Some survivors shut down emotional responses entirely. After having emotions consistently invalidated and weaponised, the safest strategy becomes feeling nothing. Survivors describe this as “going blank” or “shutting down.” Others split experience into separate compartments to manage overwhelming information. The survivor might maintain separate mental files: “good partner” versus “abusive partner,” “me at work” versus “me at home,” each compartment protected from information that would create cognitive dissonance.

Some survivors develop gaps in memory for parts of the abusive relationship. The brain protects by failing to consolidate traumatic memories or by making them inaccessible. This can later complicate recovery as the survivor struggles to reconstruct what happened.

Therapeutic Approaches: Pathways to Recovery

Trauma-Informed Therapy Principles

Effective treatment for gaslighting survivors must be trauma-informed, recognising that traditional approaches may inadvertently replicate abusive dynamics.

The therapist must believe the survivor’s account without requiring proof. After experiencing chronic disbelief, survivors need their reality validated. A therapist who questions or minimises the survivor’s experience replicates the gaslighting dynamic. This does not mean accepting everything uncritically but rather establishing that the survivor’s experience is a valid starting point. The therapeutic stance: “I believe you. Let’s work together to understand what happened.” This foundation allows exploration without defensiveness.

Before processing trauma, survivors need practical safety—out of the abusive situation—and psychological stabilisation: affect regulation, grounding skills, symptom management. Trauma processing before stabilisation can retraumatise 546 . For gaslighting survivors, stabilisation includes developing capacity to trust their own perceptions again. Reality-testing exercises, keeping journals to track objective events, and validating emotional responses all help rebuild this foundation.

Therapy must avoid replicating the power imbalance of the abusive relationship. The therapist offers options, respects the client’s choices, and explicitly acknowledges the client as expert on their own experience. Directive approaches or authoritarian therapeutic styles can trigger the survivor’s trauma responses. Trauma processing must occur at the survivor’s pace. Pushing too fast can overwhelm; moving too slowly frustrates. The therapist follows the client’s lead, helping them modulate exposure to traumatic material. This pacing respects that the survivor, not the therapist, knows their capacity.

Understanding the survivor’s cultural context, social position, and specific vulnerabilities helps avoid victim-blaming. Why someone stayed, how they were trapped, what barriers they faced—these require contextual understanding, not judgement about what they “should” have done.

Specific Therapeutic Modalities

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

CPT 1029 addresses trauma-related beliefs and stuck points—the problematic cognitions maintaining distress. Common stuck points for gaslighting survivors:

-

“I can’t trust myself.”

-

“I’m crazy/broken/damaged.”

-

“I caused the abuse by being too sensitive.”

-

“I should have known better/left sooner.”

-

“No one will believe me.”

-

“I’ll never be able to trust anyone again.”

CPT helps examine these beliefs, identify where they originated (the gaslighter’s messaging), evaluate evidence for and against them, and develop more balanced perspectives. The process rebuilds cognitive capacity to reality-test beliefs rather than accepting distorted narratives.

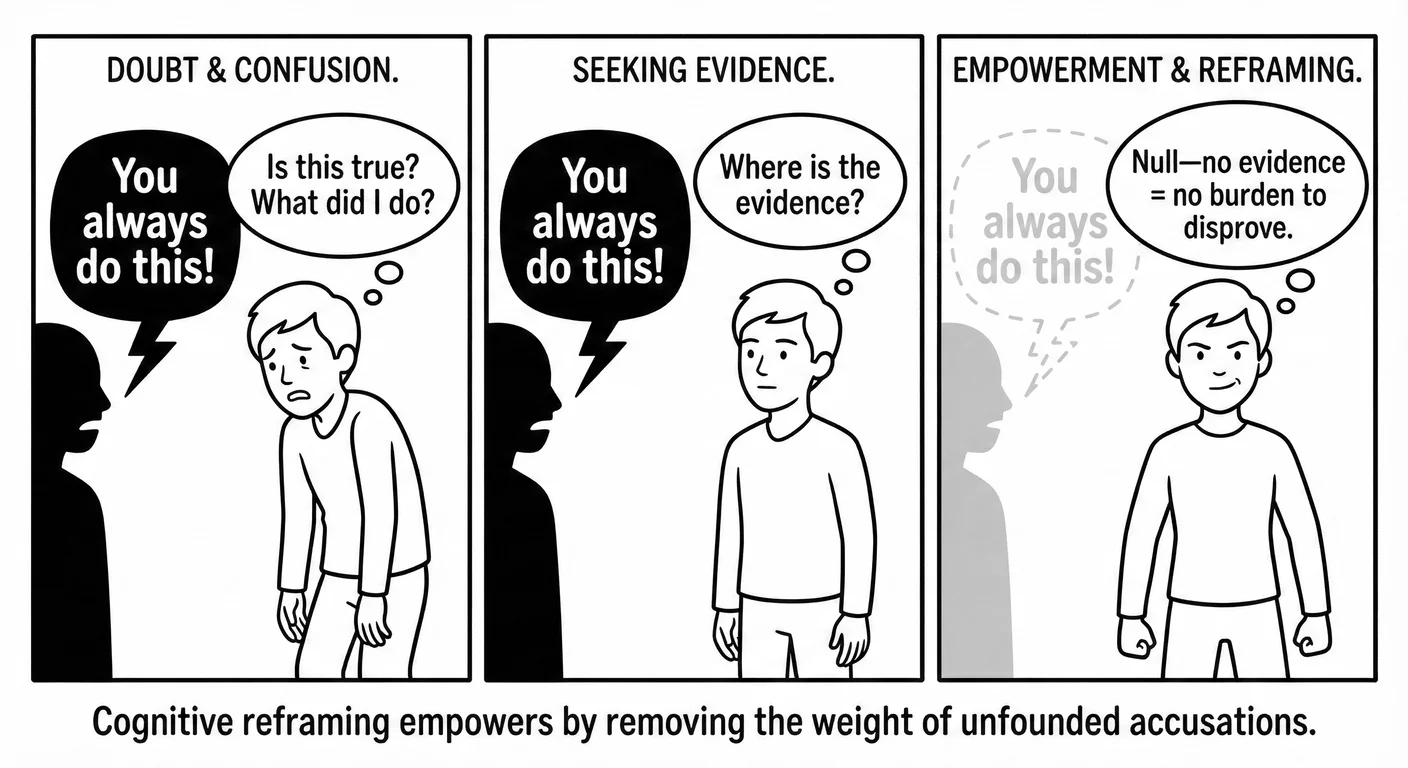

The Null Protocol: Evidence-Based Self-Defence

Complementing formal therapeutic approaches, survivors can develop a practical cognitive tool for real-time protection against gaslighting tactics. The null protocol applies the logical concept that statements without evidence are simply void—neither true nor false—as a systematic practice.

The protocol operates through three steps.

Step 1: Recognition. When faced with an accusation, characterisation, or statement about your behaviour, memory, or perception, pause before the instinctive response of self-examination. Ask: “Is there evidence being presented here, or is this a bare assertion?”

Step 2: Evidence Request. If no evidence accompanies the statement, respond with calm inquiry rather than defensive argument: “Can you give me a specific example?” “What makes you say that?” “When did that happen?” This shifts the burden of proof to the accuser, where it belongs.

Step 3: Evaluation. If the accuser provides evidence, evaluate it fairly. If the accusation is valid, acknowledge it. If the evidence is inadequate or absent, recognise the statement as null, not requiring disproof, simply void.

The power of the null protocol lies in what it prevents: the exhausting cycle of self-examination, memory-searching, and doubt that gaslighting triggers. When someone says “You always do this,” the gaslit victim traditionally spirals: Do I always do this? When have I done this? Maybe I do this without realising… The null protocol interrupts this spiral: “Always” is a strong assertion. Where is the evidence? If there is none, this is null—I do not need to disprove it.

This approach integrates well with CPT’s cognitive restructuring. Where CPT helps survivors examine and revise trauma-related beliefs after the fact, the null protocol provides in-the-moment protection against new attempts at reality distortion. The combination—therapeutic processing of past damage combined with active defence against ongoing manipulation—proves particularly effective for survivors still in contact with narcissistic family members or co-parents.

Chapter develops the null protocol more fully, exploring its theoretical foundations and providing practical examples. Appendix provides quick-reference versions of the Null Protocol and Documentation Protocol for immediate use. This cognitive tool bridges understanding gaslighting and actively defending against its effects.

Trauma-Processing Modalities

Chapter provides detailed coverage of evidence-based trauma therapies including EMDR, Internal Family Systems, and Somatic Experiencing.

EMDR (see Chapter ) proves particularly valuable for gaslighting because the bilateral stimulation may help integrate split mental compartments, allowing the survivor to hold contradictory information simultaneously. DBT 748 addresses four domains gaslighting damages: mindfulness—rebuilding capacity to observe one’s experience without doubting it; distress tolerance—managing emotional pain without dissociating or self-destructing; emotion regulation—learning that emotions are valid signals rather than personal flaws; and interpersonal effectiveness—maintaining relationships while also maintaining self-respect, capacities gaslighting teaches are incompatible.

IFS (see Chapter ) helps gaslighting survivors make sense of internal fragmentation: the part that wants to forgive, the part that is angry, the part that doubts, the part that knows the truth. Somatic Experiencing (Chapter ) addresses the body-based disconnection gaslighting creates (“I cannot trust what I feel”).

The Therapeutic Relationship as Healing

Beyond specific techniques, the therapeutic relationship itself provides healing.

The therapist offers stable, trustworthy presence—corrective emotional experience for someone whose trust was betrayed. Experiencing a relationship where reality is shared, emotions are validated, and boundaries are respected begins healing interpersonal trauma. The therapist mirrors back the survivor’s experience accurately, validating their perceptions and emotions. This reverses the gaslighting dynamic where the victim’s experience was constantly distorted or denied. Over time, survivors internalise this validation, developing capacity for self-validation.

The therapist provides external reality check when the survivor doubts their perceptions—through helping them evaluate evidence, identify distortions, and trust their own assessment process, without imposing the therapist’s view of what is real. The therapist’s confidence in the survivor’s capacity to perceive reality helps rebuild that capacity. Inevitable misunderstandings or conflicts in therapy provide an opportunity for healthy rupture and repair. When the therapist makes mistakes and genuinely takes responsibility and repairs the relationship, this demonstrates that relationships can be safe even when imperfect—a corrective experience for someone whose partner never took responsibility.

Group Therapy and Peer Support

Beyond individual therapy, group interventions offer particular benefits.

Hearing others describe similar experiences validates that gaslighting was real, not imagined. The relief of discovering “I’m not alone, I’m not crazy” can be immense. Groups break the isolation that gaslighting created. When multiple people independently describe the same manipulative tactics and patterns, this provides powerful reality validation. The survivor cannot dismiss everyone as misperceiving.

Seeing others further along in recovery provides hope and models for healing. The survivor who feels irreparably damaged encounters someone who felt the same way five years ago and has rebuilt their life. Groups also offer a low-stakes environment to practice healthy interpersonal skills: setting boundaries and managing conflict. These skills, damaged by gaslighting, can be rebuilt through supported practice. The gaslighter’s isolation tactics lose power when the survivor develops a support network of people who understand their experience. Mutual aid and genuine connection counter the gaslighter’s message that the survivor is unlovable or too damaged for relationships.

Medication Considerations

Medication does not treat gaslighting trauma directly, but it can address specific symptoms.

SSRIs can reduce depression and intrusive thoughts in some survivors 34 . They do not address underlying trauma but may stabilise mood enough to engage in therapy. Addressing sleep disturbance improves overall functioning, though dependency risks with sleep medications require careful management, and some survivors with substance abuse history need alternative approaches.

Short-term use of benzodiazepines—diazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam—for acute anxiety or panic can help, but long-term use poses addiction risks. Non-addictive alternatives like hydroxyzine, an antihistamine with anxiolytic properties, may be preferable. Trauma-specific medications also show promise: prazosin, an alpha-1 blocker that reduces trauma-related nightmares by blocking norepinephrine’s effects during REM sleep; propranolol for trauma memory reconsolidation blocking; and ketamine for treatment-resistant depression—though all require specialised administration.

The key principle: medication as adjunct, not replacement, for trauma therapy. Pills can reduce symptoms but cannot rebuild the capacity to trust one’s reality or restore the sense of self that gaslighting damaged.

Survivor Stories: Voices from the Other Side

Research Voices: The Slow Awakening

In 2023, researchers Klein, Li, and Wood conducted one of the first large-scale qualitative studies of gaslighting survivors, collecting detailed accounts from sixty-five people who had experienced reality manipulation in romantic relationships. 670 Their findings illuminate patterns that appear across nearly every survivor’s story.

One participant described the classic trajectory: “He’d tell me I’d agreed to things I knew I hadn’t. Small things at first, where we’d go to dinner, what we’d said about holiday plans. When I’d correct him, he’d look genuinely hurt that I didn’t remember. That’s when I started questioning my memory.” The researchers found that gaslighters who were motivated by a desire to control engaged in a wider variety of coercive tactics, including setting rules, verbal abuse, property damage, and threats.

The study documented how survivors’ sense of self eroded over time. Most subjects reported that they felt as though they had lost part of themselves, that their self-concept had “shrunken,” or that they’d become a “shell of themselves.” One participant told the researchers: “Within a few years, I was keeping a journal trying to track reality because I couldn’t trust myself. But then he told me the journal itself proved I was obsessive and paranoid. I stopped trusting my own documentation of reality.”

Career and social consequences proved devastating. Accusations of incompetence, characteristic of gaslighting, combined with attempts to isolate the survivor from friends and family. One woman reported: “I’d been on partner track, but I couldn’t make decisions anymore. I’d second-guess everything. In meetings, I’d stay silent rather than risk being wrong. My confidence drained away.”

The research confirmed what clinicians have long observed about recognition: it rarely arrives as a single moment of clarity. “Naming it felt like putting on glasses after years of being told your vision was fine,” one participant explained. Yet even after recognition, leaving proved extraordinarily difficult. Financial abuse and the sheer exhaustion of years of reality manipulation created barriers that took months or years to overcome.

Perhaps most significantly, the study found that recovery required social reconnection. Despite reports of increased mistrust, socialising was the activity most reported in response to questions about recovery. Engaging or re-engaging with others helped many survivors regain a sense of self. “I had to learn to trust myself again from scratch,” one survivor explained. “For years, I’d ask friends: ‘Did I say that? Do you remember it this way?’ The capacity to trust one’s own mind had to be rebuilt deliberately.”

Jackson MacKenzie: Male Victim, Finding Purpose

Jackson MacKenzie’s experience illustrates that gaslighting is not gendered, and that male victims face particular challenges in recognition and disclosure. His story also illustrates how personal devastation can become collective healing.

“Years ago, this cycle had me thinking I’d never be happy again,” MacKenzie writes in Psychopath Free. 782 “Falling in love had somehow wiped out my entire sense of self. Instead of being joyful and trusting, I had become an unrecognisable mess of insecurities and anxiety.” Like many survivors, he initially blamed himself. The relationship had seemed perfect at first: the intense attention, the apparent understanding, the feeling of being truly seen for the first time.

The gaslighting manifested through reality distortion and isolation: “She’d describe conversations with my friends where they’d complained about me. I never checked these conversations, why would she lie? I started pulling away from everyone. Years later, reconnecting with old friends, I discovered those conversations never happened. She’d invented everything.”

MacKenzie’s turning point came through research. “A lucky Google search led me to psychopathy, which led me to the friends who saved my life, which led us to cofound a tiny online recovery community, which now reaches millions of survivors every month.” That community became PsychopathFree.com, one of the largest online support networks for survivors of emotional abuse.

Even with recognition, the aftermath proved devastating: “As a man, admitting emotional abuse felt emasculating. People asked what I was complaining about, no violence, just ‘communication problems.’ The invisibility of my wounds meant they looked self-inflicted. But manipulation by a trusted intimate isn’t something you can logic your way out of. It’s trauma.”

MacKenzie’s recovery became inseparable from helping others. “At first I didn’t realise that my story was so many other people’s story. Initially I just thought I was trying to survive an isolated cataclysmic event.” His books Psychopath Free and Whole Again have become foundational texts in the survivor community, translated into multiple languages.

“The hardest part was forgiving myself for staying,” he reflects. “I’m not stupid. But that doesn’t protect against lies from someone you love. That’s what I’d want other survivors to know: it’s not weakness. The same capacity for trust and love that made you vulnerable is also what makes you capable of real connection. The abuse happened because you’re human, not because you’re broken.”

Randi Fine: Gaslighting in Parental Relationships

Not all gaslighting occurs in romantic partnerships. Randi Fine’s memoir Cliffedge Road illustrates what happens when the gaslighter is a parent, and when the abuse begins before the child has any other reality to compare it to. 388

Fine describes growing up with a mother whose love was conditional and laced with reality distortion. “I always felt something was off, though I didn’t have language for it until my thirties,” she writes. “If I cried, I was ‘too sensitive.’ If I remembered promises she didn’t keep, I’d ‘made things up.’ If I felt hurt, I was ‘selfish’ and ‘ungrateful.”’ The gaslighting was so complete that Fine spent decades believing she was the problem.

The impact on her development was severe. Fine became what she calls a “people-pleaser”, constantly seeking external validation because her own perceptions had been systematically invalidated. “I needed other opinions; my opinions had always been wrong. In relationships, I’d become whoever my partner needed. I had no stable sense of who I actually was.”

Recognition came slowly, through therapy and research. “My therapist kept circling back to my mother. I’d describe interactions, and she would say, ‘That’s gaslighting. That’s invalidation. That’s emotional abuse.’ I’d resist: ‘But she’s my mother. She loves me. She sacrificed for me.”’ Fine eventually understood that both could be true: her mother could have loved her and still have caused significant psychological harm.

The complication with parental gaslighting is that it begins in childhood. “When romantic partners gaslight you, you have pre-abuse identity to recover,” Fine explains. “When parents gaslight you from childhood, there’s no pre-abuse self. You have to build identity from scratch. It’s not recovery; it’s creation.” She had to discover in her thirties who she was, what she liked, what she believed—developmental tasks most people complete by twenty-five.

Fine’s relationship with her mother remained complicated until her mother’s death. “She never acknowledged the gaslighting. In her mind, I was an ungrateful daughter inventing problems with a therapist’s encouragement. I had to accept that closure would never come from her. I had to become my own validating parent.”

Today, Fine works as a narcissistic abuse recovery coach, helping others navigate the same terrain she crossed. Her memoir, she says, exists “not only to regain agency but also to help others with similar experiences feel less alone.” Cliffedge Road stands as the first book to characterise the lifelong progression of complications narcissistic parental abuse causes, from childhood through multiple adult relationships, showing how early gaslighting shapes every subsequent attachment.

Common Themes in Recovery

Across survivor stories, common themes emerge.

Learning the term “gaslighting” and recognising the pattern provided immense relief. Survivors describe feeling “like a fog lifted” or “putting on glasses.” Having language for the experience validated that it was real. Yet recovery took years, not months. Rebuilding trust in one’s own perceptions, healing C-PTSD symptoms, and reconstructing identity proved lengthy processes. Survivors emphasise patience with themselves and resistance to pressure to “move on” quickly.

Whether therapy, support groups, or understanding friends, external validation proved essential. No survivor recovered in isolation. Having others confirm “Yes, that was abuse. No, you’re not crazy” broke the gaslighting’s hold. Many survivors struggle with shame about staying, about not recognising the abuse sooner, about their behaviour during the relationship. Healing requires forgiving themselves and recognising that they did the best they could with the information and resources available.

All survivors described the work of learning to trust their perceptions again: keeping journals, reality-checking with trusted people, practicing making decisions, tolerating the discomfort of uncertainty. The capacity to trust one’s own mind had to be rebuilt deliberately. Many survivors reported that recovery, while painful, produced growth: deeper Empathy Empathy The capacity to understand and share another person's feelings, comprising both cognitive (understanding) and affective (feeling) components—often impaired in narcissism. , clearer boundaries, greater self-knowledge, appreciation for authenticity, and commitment to healthy relationships. The trauma, once processed, sometimes yielded wisdom.

Voices of Hope

What do survivors want others to know?

From Joelle Tamraz: “Stories of people who have had experience with cults, abusive gurus, and coercive partners are important because they help us understand how any of us could fall victim to the right abuser. Many people hold the misconception that they cannot fall under the spell of an abuser. In fact, so many of the people who do experience this kind of coercive control are intelligent, driven, and principled.”

From Jackson MacKenzie: “It happens to anyone, regardless of gender, education, or intelligence. The shame keeps us trapped. We think we should have known better. But manipulation by a trusted intimate isn’t something you can logic your way out of. It’s trauma. Treat it as such.”

From Randi Fine: “For those gaslit in childhood by parents: the work of building identity from scratch is hard, but it’s possible. You can learn who you are. You can learn to trust yourself. And you can break the cycle. Your children don’t have to inherit your trauma.”

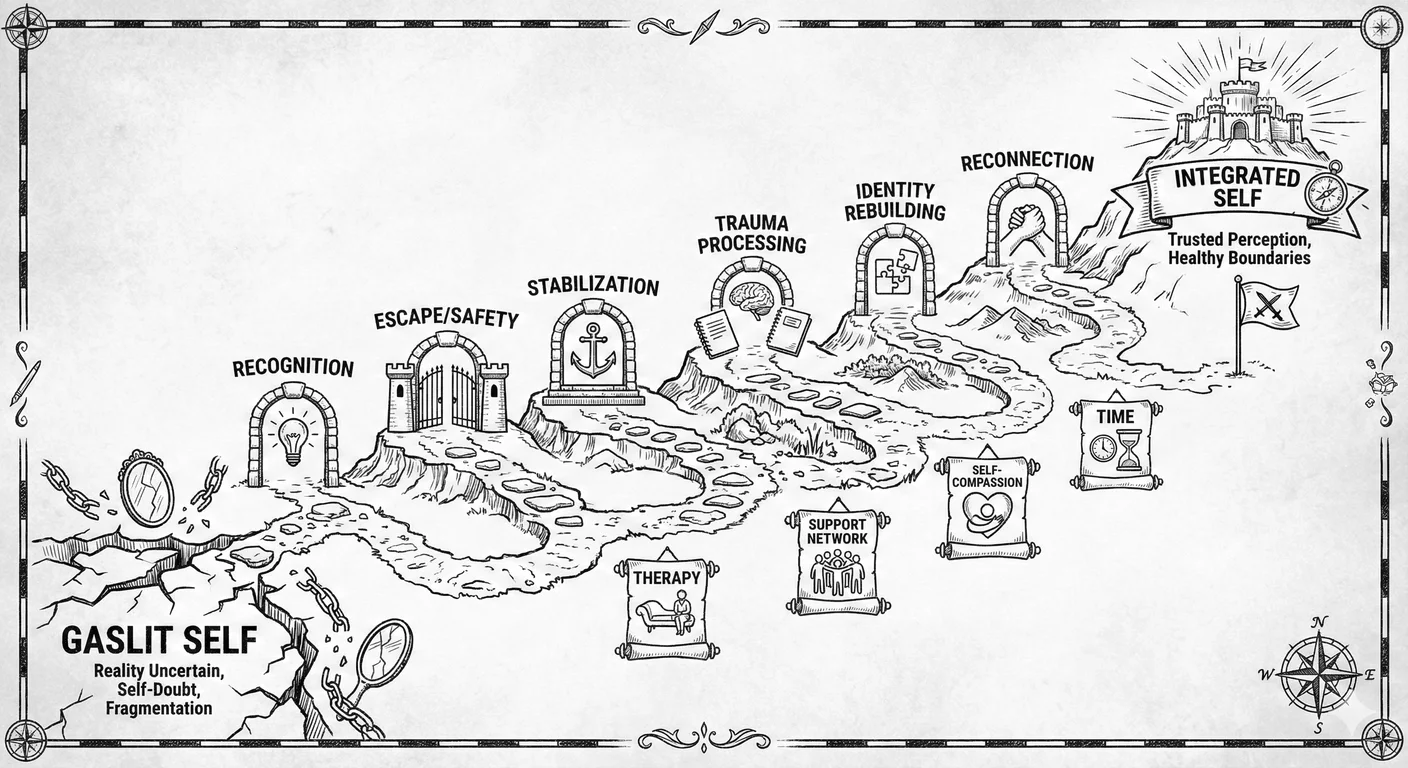

From the Klein et al. research participants: “Recovery is possible. You’re not permanently broken. The capacity to trust yourself can be rebuilt. It takes time and professional help. But you can reclaim your reality. You can heal. The gaslit self can become the integrated self.”

Conclusion: Reclaiming Reality as Revolutionary Act

Gaslighting is among the most pernicious forms of psychological abuse precisely because it targets the foundation of human functioning: the capacity to perceive reality accurately and trust one’s own mind. When narcissists systematically distort reality to maintain grandiosity and control, they do not just lie—they colonise the victim’s consciousness, replacing the victim’s perception with the narcissist’s preferred narrative.

Gaslighting devastates far beyond anxiety, depression, or PTSD. It produces existential crisis: if you cannot trust your own mind, what remains of your selfhood? The gaslit victim becomes hollow, filled with doubt, dependent on external validation for the most basic assessment of reality. This dissolution of self serves the narcissist perfectly: the victim becomes pliable, unable to challenge the narcissist’s grandiose narrative because they lack the confidence to assert an alternative truth.

Gaslighting has distinct features marking it as a form of psychological abuse.

Gaslighting is not occasional lying or misunderstanding. It is persistent, patterned reality distortion serving specific psychological functions for the perpetrator, primarily protecting grandiosity and maintaining control. The symptoms are not overreaction or sensitivity but legitimate trauma responses to sustained psychological assault. Complex PTSD, not simple relationship dysfunction, appropriately describes the clinical picture.

Smart, capable, educated people fall victim to gaslighting. The myth that only weak or foolish people are manipulated keeps victims trapped in shame. The vulnerability lies in normal human reliance on trusted intimates for reality validation, independent of any deficit on the victim’s part. Healing is not just processing traumatic memories but reconstructing fundamental abilities: trusting one’s perceptions, making decisions confidently, maintaining boundaries, and forming secure attachments. This deep repair explains why recovery takes years.

While mental health professionals increasingly recognise gaslighting’s severity, broader society often minimises it. “Just leave” or “Get over it” responses fail to grasp that gaslighting has destroyed the victim’s capacity to trust their judgement about whether leaving is necessary or even possible.

The cultural moment we are experiencing, where gaslighting has entered popular discourse, offers both opportunities and risks. The opportunity: increased recognition, validation of survivors, and social pressure against manipulative behaviour. The risk: over-diagnosis, where normal disagreements get labelled as gaslighting, diluting the term’s meaning and potentially providing narcissists new vocabulary to weaponise against victims (“You’re gaslighting ME by not accepting my version of events”).

Recovery from gaslighting involves rebuilding the capacity to trust one’s own perceptions. Survivors who doubt themselves in specific relationships but not others may be responding to systematic manipulation rather than personal deficiency. A useful diagnostic pattern: context-specific self-doubt that lifts in other environments suggests external causation rather than internal pathology.