Introduction: Behind the Grandiose Mask

The psychiatrist Arnold Cooper 265 described a pattern he observed across decades of treating individuals with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) A mental health condition characterised by an inflated sense of self-importance, need for excessive admiration, and lack of empathy for others. : moments of devastating clarity when the grandiose facade momentarily fails. In one session, a patient, a successful executive in his fifties, articulated this experience: “I’ve spent my whole life being special. But I don’t know who I am when no one’s watching. I don’t think there’s anyone there.” Cooper noted that such insights were typically fleeting, followed by rapid reconstitution of defences, but they revealed the deep emptiness at narcissism’s core.

This recognition of emptiness beneath the grandiose persona exemplifies the narcissist’s deepest fear realised. Beyond victims and families, a clinical reality is often overlooked: the narcissist suffers too, in ways that illuminate the disorder’s tragic nature without excusing their behaviour or diminishing victims’ trauma.

The narcissist’s suffering differs in kind from their victims’. Victims suffer from external harm inflicted by someone else. The narcissist suffers from internal deficits that no external validation can fill. They construct elaborate false selves to mask a core experience of worthlessness, spending their lives fleeing from an emptiness that pursues them relentlessly. Every relationship fails because genuine intimacy would expose the void. Every achievement rings hollow because external success cannot repair internal damage. Each passing year strips away another defence, bringing them closer to the confrontation with self they have spent a lifetime avoiding.

This suffering does not engender sympathy in the way victims’ suffering does, primarily because narcissists have agency in perpetuating their pathology and harming others. Yet their internal experience illuminates why narcissistic patterns persist despite causing misery to the narcissist themselves. The desperate quality of Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. -seeking reflects not mere selfishness but existential terror of confronting inner emptiness. The defences protecting against unbearable shame resist therapeutic intervention. The pattern represents substantial waste: lives spent maintaining elaborate defences, without authentic connection or genuine self-worth.

A Narcissist’s Inner World: Understanding the Void

The False Self and True Self Split

Previous chapters traced the false self’s developmental origins (Chapter ), its distinction from borderline fragmentation (Chapter ), and its formation in children of narcissistic parents (Chapter ).

The true self—the authentic person carrying the original wound of feeling unlovable—remains buried beneath conscious awareness. The false self emerges as grandiose persona: special, superior, entitled, admirable. Through it, the narcissist relates to others and constructs their life narrative. It is performance built on denial.

The false self must be maintained constantly. Every relationship serves to validate it. Every achievement proves its superiority. Every criticism threatens to expose the worthless true self beneath. The exhausting maintenance never ends.

As Winnicott observed, the false self complies with external demands at the cost of genuine selfhood. 1333 The narcissist does not know who they actually are because their entire existence is constructed around denying authentic experience. Children forced to serve as mirrors (Chapter ) experience one side of this dynamic; the narcissist experiences the emptiness from inside the mirror itself.

The Experience of Emptiness

Narcissists who achieve therapeutic insight consistently report chronic emptiness. It is an existential void, beyond boredom or loneliness: a sense that nothing inside feels real or substantial.

Dr Otto Kernberg, who extensively studied narcissistic personality, describes this emptiness as the subjective correlate of the split between grandiose self and devalued self. 649 The narcissist experiences themselves as hollow because they lack an integrated self-concept. The inflated false self and the deflated true self exist, but there is no coherent middle ground representing authentic identity.

Narcissists describe this emptiness in therapy when defences weaken.

“I feel like a shell. Like there’s nothing inside me. I perform being a person, but I don’t know what I actually feel or want.”

“It’s like living behind glass. I watch life happen but don’t feel part of it. Everything feels fake, including me.”

“I’ve accomplished so much, but it means nothing. Each achievement is briefly satisfying, then the emptiness returns. I thought success would fill it, but it never does.”

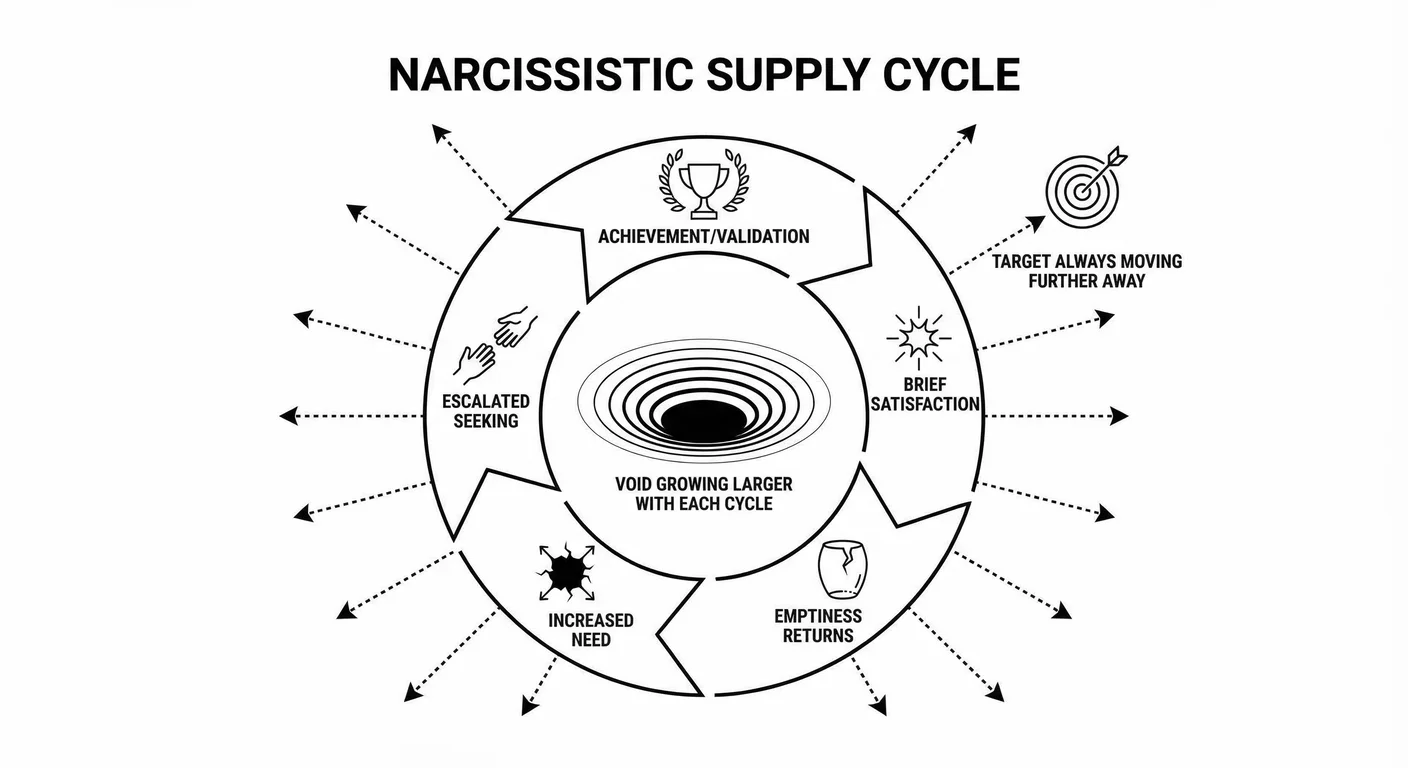

This emptiness drives the relentless supply-seeking examined in Chapter . The narcissist pursues admiration and validation, anything generating temporary sense of aliveness. Like drugs for an addict, the effect is temporary. The emptiness returns, demanding another fix. No amount of supply permanently satisfies because external validation cannot repair internal deficit.

The emptiness also explains narcissists’ difficulty being alone. Solitude means confronting the void without distraction. The workaholic narcissist and the serial relationship narcissist both flee the same thing: silence that would reveal the hollowness within.

Shame as Core Affect

Underneath the grandiosity lies unbearable toxic shame. Helen Block Lewis 735 and Gershen Kaufman 639 distinguish shame from guilt: guilt says “I did something bad”; shame says “I am something bad.” The narcissist carries toxic shame: the belief that their core self is fundamentally flawed, unlovable, worthless. This shame is so painful that it must be defended against at all costs. The grandiose false self exemplifies the defence: “I’m not worthless; I’m superior.” But the shame never disappears; it lurks beneath the surface, threatening to emerge whenever the false self is challenged.

Hence Narcissistic Rage Narcissistic Rage An explosive or cold, calculated anger response triggered when a narcissist experiences injury to their self-image, far exceeding what the situation warrants. . When criticised or confronted with evidence of imperfection, the narcissist does not experience simple annoyance. They experience shame activation, the momentary awareness of the worthless true self. The rage functions to defend against this unbearable feeling: attack the source of shame, project it onto others, reassert grandiosity aggressively.

Shame also explains the narcissist’s perfectionism and intolerance of mistakes. Any error threatens to confirm their worst fear about themselves. A minor failure that others would dismiss as a learning experience feels to the narcissist like proof of core defectiveness. All-or-nothing thinking follows: either perfect or worthless, no middle ground.

Shame requires vulnerability to heal. Genuine shame resilience develops through having shame experiences witnessed and accepted by caring others. 166 The narcissist’s defences prevent exactly this. They remain trapped in a shame cycle: shame drives defensive grandiosity, which prevents authentic connection, which perpetuates isolation intensifying the shame. Breaking this cycle therapeutically remains one of the field’s most difficult challenges.

Dr Miriam Chen, a psychoanalyst who has treated personality disorders for thirty years, describes a patient she saw for four years. “Bernard was a retired surgeon. Brilliant career, three ex-wives, estranged from all four children. He came to me after a heart attack because his cardiologist suggested stress reduction. For two years, every session was about how others had failed him. His wives were ungrateful. His children were selfish. His colleagues were jealous. I was incompetent.” In year three, something shifted. “He came in one day and said, ‘I think I’ve been lying to you.’ I waited. He said, ‘I don’t think my children are selfish. I think they’re scared of me.”’ They sat with that for several sessions. “We had perhaps six months where he could tolerate knowing he’d hurt people. He cried once, talking about his youngest daughter.” Then his fourth wife filed for divorce. “Suddenly I was conspiring against him. His daughter had poisoned her. Everyone was the enemy. He stopped coming.” She is asked if those four years were wasted. “He’s seventy-eight. I don’t have an answer to that.”

The Absence of Self-Cohesion

Healthy identity formation requires integration across time and contexts. A cohesive self experiences continuity, internal consistency, and authentic agency. Narcissists lack this integration. 676 Where the borderline has too little self, the narcissist has a rigid false self masking fragmentation beneath. They present disconnected performances across contexts—charming publicly, controlling privately—without recognising the contradictions.

This fragmentation shapes the narcissist’s relationship to truth. They are not necessarily consciously lying when presenting contradictory versions of events. Their relationship to objective reality is loose because they lack a stable internal reality against which to calibrate. What matters is what serves the false self in the moment. Gaslighting comes naturally to them: they genuinely believe whatever version of reality the false self currently requires.

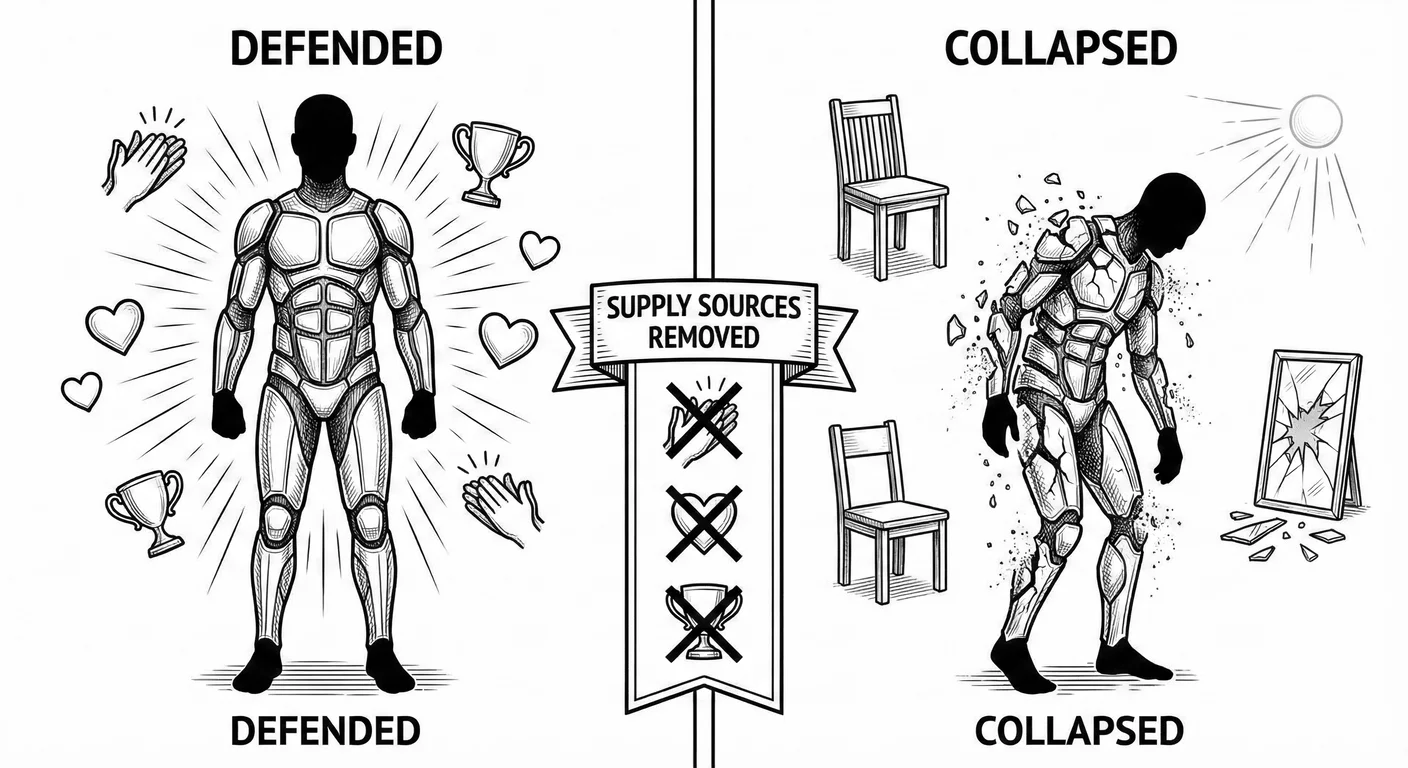

When life challenges mount, the fragile false self structure threatens collapse. Without an integrated self providing stability, the narcissist may decompensate dramatically: depression, rage, paranoia, substance abuse, or psychotic-level denial. This is the narcissistic crisis: when compensatory mechanisms fail and the void becomes conscious.

The Inability to Love

Narcissists consistently cannot love genuinely. They can feel attachment, desire, need. But mature love—caring about another’s wellbeing separate from how they serve your needs, valuing their subjectivity, accepting their separate existence—requires capacities narcissists lack. They lack Object Constancy Object Constancy The psychological ability to maintain a stable, positive connection to someone even when frustrated, separated, or in conflict with them—often impaired in narcissism. .

Kernberg distinguishes between libidinal object constancy—maintaining attachment across time and absence—and object love, which involves caring about the object’s welfare independent of one’s needs. 649 Narcissists can develop the former but not the latter. They maintain attachment to people who provide supply, but they relate to these people as objects serving narcissistic functions rather than as separate subjects with independent value.

The loneliness is crushing. The narcissist is surrounded by relationships but genuinely alone. No one knows their true self because they hide it even from themselves. Every interaction is transactional: what can this person provide? The authentic mutuality of healthy love—where both people care about each other’s experience for its own sake—remains foreign.

Some narcissists report awareness of this deficit in rare moments of insight.

“I watch my wife care about things, her friends’ problems, stories she reads, causes she supports. She feels things about others’ experiences. I don’t. I pretend to care because I know I’m supposed to, but I’m always thinking about how it affects me. I feel like I’m missing something everyone else has.”

This incapacity for love becomes more acute with aging. The narcissist approaches end of life without having formed the deep attachments that give life meaning. They have had many relationships but no genuine intimacy. They have been admired but not truly known. This isolation, initially protective, becomes self-perpetuating.

Chronic Emptiness: The Hunger

The Hedonic Treadmill on Steroids

Psychologists describe the hedonic treadmill: people adapt to positive life changes, returning to baseline happiness. 158 The lottery winner’s joy fades; the promotion’s satisfaction wanes. For narcissists, this adaptation occurs more rapidly and more completely, because external achievements never address internal deficit.

The narcissist achieves a goal: promotion, award, romantic conquest, wealth milestone, social recognition. Briefly, they feel validated. The false self seems confirmed: “See? I am special.” But the effect is temporary. Within days, sometimes hours, the emptiness returns. The achievement becomes part of baseline expectation rather than a source of lasting satisfaction. The supply already consumed requires replacement.

The need for achievement escalates. If one promotion provided temporary relief, perhaps the next will last longer. If one relationship’s idealisation phase felt good, perhaps the next will sustain it. If one million dollars proved insufficient, perhaps ten million will satisfy. But the target keeps moving because the real problem is not external circumstance but internal structure.

Dr Drew Pinsky, who has studied narcissism extensively in celebrity populations, notes that fame exemplifies the ultimate validation: millions of people providing validation simultaneously. 1356 Yet celebrities with narcissistic personality often report deep emptiness despite fame’s validation. They achieve the supply most narcissists fantasise about, yet it does not fill the void. The problem is not insufficient supply but the structural inability to internalise it.

Henrik sold his third company at forty-four. The acquisition made him wealthy enough to never work again. “I remember sitting in the lawyer’s office after the signing. Everyone’s congratulating me. Champagne. I’m smiling, saying the right things.” He bought a house in Marbella, a boat, travelled. “I’d wake up and feel this… flatness. Like the colour had drained out. I thought maybe I needed a new project, so I started another company. The launch went well. Same feeling.” He’s been through two marriages, currently dating a woman twenty years younger. “People assume I’m satisfied. I don’t know what satisfied would feel like.” He doesn’t call it emptiness. He calls it “waiting for something to start.”

Why Supply Never Satisfies

The insatiable hunger amid endless feeding has a precise psychological explanation.

Healthy self-esteem develops through early experiences of being valued for one’s authentic self. The child feels genuinely seen, accepted with flaws, and loved unconditionally (for who they are, independent of achievements). A stable internal sense of worth develops that does not require constant external confirmation. Challenges and criticism cause temporary doubt, but the foundational sense of adequacy remains. 146

The narcissist never developed this foundation. Their early experience taught them that love was conditional: be special, meet parent’s needs, and you’ll be valued. Their authentic self, with needs, vulnerabilities, flaws, was rejected or ignored. The core wound followed: “My true self is unlovable.”

Validation-seeking attempts to heal this wound through external validation but fails for several interlocking reasons.

Supply validates the false self (“You’re so successful,” “You’re so attractive,” “You’re so special”), but it is the true self that feels worthless. The validation goes to the persona, not the person. It is like receiving praise for a performance while knowing you are acting. Because narcissists lack an integrated self-structure to anchor it, external validation cannot be internalised as stable self-worth. Each instance of supply provides momentary relief but cannot be stored as a lasting resource. The self is too fragmented to hold it.

Each validation of the false self implicitly invalidates the true self: “I’m loved for being special, not for being me.” This deepens the split and increases the terror of the false self failing. The narcissist becomes more dependent on supply, not less. Like a leaking vessel, the narcissist needs constant refilling. But the leak is the missing foundation of unconditional early love. No amount of conditional later validation can substitute for what was absent in formative years.

You cannot fill their void, no matter how much you give. The Supply Starvation Strategy in Appendix operationalises this insight into protective action.

Escape Through Intensity and Fantasy

Unable to find sustainable satisfaction in ordinary life, narcissists pursue intensity: extreme sports, high-risk ventures, sexual conquests, substance abuse, gambling, dramatic conflicts. The dopamine surge provides relief from chronic emptiness. But like any addiction, tolerance develops. 649 The stimulus that once worked requires escalation: bigger risks, newer partners, stronger substances. Some narcissists grow increasingly reckless over time, requiring ever-intensifying stimulation to achieve the same temporary relief.

Ordinary happiness cannot compete. Simple pleasures, quiet moments, and stable relationships trigger the emptiness that intensity keeps at bay. Sitting quietly with a partner, playing with children, enjoying nature—these require a capacity for authentic presence that the narcissist lacks.

When external intensity fails, many retreat into elaborate fantasy: sustained parallel narratives where the narcissist is the hero or tragic figure they believe themselves to be. The fantasies provide supply when external sources fail, offer grandiose scenarios confirming superiority, and protect against shame by reframing failures as others’ fault. But fantasy ultimately intensifies emptiness—time spent in fantasy is time not spent in authentic engagement with reality, and the gap between fantasy and reality widens.

Some narcissists become so invested in fantasy that reality becomes optional. They believe their own lies, rewrite history to match preferred narrative, and genuinely seem convinced by delusions of grandeur. This is motivated cognition—believing what the false self requires to be true, regardless of evidence—rather than psychosis.

Anhedonia and Depression

Many narcissists experience what appears clinically as depression: low mood, emotional numbing, low energy, hopelessness. But narcissistic depression differs from major depressive disorder. 1053 The primary experience is emptiness rather than sadness, grandiose irritability rather than heaviness, shame rather than guilt. Yet narcissists rarely identify themselves as depressed; they experience others as disappointing them.

The anhedonia proves particularly pronounced. The narcissist can feel pleasure—they clearly enjoy validation—but activities themselves do not matter. Only their supply value matters. A beautiful sunset, a good book, a delicious meal: these have no intrinsic value because they do not provide validation. The narcissist’s paradox: surrounded by achievements, relationships, experiences, yet inwardly empty. External life and internal experience exist in complete disconnect.

Aging and Collapse: When Defences Fail

Age as Narcissistic Threat

Aging presents particular challenges for everyone, but for narcissists it represents a catastrophic threat to compensatory mechanisms. Aging forces confrontation with vulnerability and mortality—experiences the narcissist has spent their life denying. 653

For somatic narcissists—those deriving worth from physical appearance or prowess—aging’s physical changes prove devastating. The attractive woman who built identity on beauty, the athletic man whose physicality defined him, the sexual narcissist whose conquest depended on youth—all face the mirror’s betrayal. Cosmetic procedures, excessive exercise, age-inappropriate clothing, and partnerships with much younger people attempt to deny aging, but reality intrudes inexorably. The intellectual narcissist faces mental changes: processing speed slows, memory becomes less reliable, learning new things proves harder. For someone whose grandiosity centred on superior intelligence, these normal changes feel like catastrophic loss of self.

By mid-life, most careers reach plateau. Promotions become less frequent, younger colleagues rise, retirement approaches. The professional narcissist faces irrelevance. They are no longer the rising star but the aging has-been. Some respond by clinging to positions beyond appropriate retirement, others by dramatic career changes attempting to recapture glory. Younger people do not recognise the aging narcissist’s past achievements. To them, the narcissist is just an older person, not the exceptional figure they believe themselves to be. This loss of automatic respect proves intolerable.

Perhaps most threatening, aging brings death closer. The narcissist who has spent their life believing themselves exceptional must confront that death comes for everyone. The grandiose fantasy of uniqueness collides with biological reality. Some narcissists become obsessed with legacy, desperate to achieve immortality through fame or lasting recognition. Others spiral into depression or rage at the universe for subjecting them to this indignity.

The Mid-Life Narcissistic Crisis

Between ages 40-60, aging’s reality drives many narcissists into crisis.

The aging narcissist may blow up long-term relationships, seeking younger partners who do not remember when they were ordinary. They project their own aging onto their partner: “You’ve let yourself go,” “You’re not the person I married.” The criticism of partner’s aging masks terror of their own. Some take desperate professional risks attempting to recapture past glory. The executive who made one successful deal thirty years ago attempts increasingly risky ventures, destroying accumulated wealth and reputation in pursuit of one more triumph proving they still have it.

Alcohol or drugs provide escape from aging’s reality. The successful professional secretly drinking to blackout, the aging athlete abusing steroids, the midlife narcissist using cocaine to feel young—substance abuse offers temporary relief from unbearable awareness. Some aging narcissists become increasingly angry and bitter, raging against the disrespect of younger people, the changing world that does not value what they value, the injustice of aging. The rage masks grief and terror.

Others double down on grandiosity. More plastic surgery, more age-inappropriate behaviour, more insistence on their specialness. The seventy-year-old dressing and acting like they are thirty, the aging businessman making increasingly grandiose claims, the retired executive insisting they could still run the company better than current leadership.

When the False Self Fails

The narcissist’s compensatory mechanisms—grandiose self-presentation and supply-seeking—require energy and cooperation from others. Aging can deplete both.

Physical and cognitive decline reduce capacity to perform the false self. The charm takes more effort. The quick wit slows. The impressive achievements belong to the past, not the present. The narcissist feels the false self slipping but lacks an authentic self to fall back on.

Opportunities for supply diminish. Retired, they lack the professional stage. Adult children see through them. Marriages fail. Health problems intrude. Younger people do not provide the recognition they crave. The supply sources dry up.

Others stop cooperating. People who once tolerated narcissistic behaviour due to the narcissist’s position or power no longer have reason to tolerate it. Adult children set Boundaries Boundaries Personal limits that define what behaviour you will and won't accept from others, essential for protecting yourself from narcissistic abuse. or go No Contact No Contact A strategy of completely eliminating all communication and interaction with a narcissist to protect mental health and enable recovery from abuse. . Younger colleagues do not defer. The aging narcissist’s demands meet resistance they are unaccustomed to facing.

When these mechanisms fail, what remains? For some, nothing. The false self collapses, and no integrated true self provides continuity. This is the Narcissistic Collapse Narcissistic Collapse A severe breakdown of the narcissist's false self defences, exposing the shame and emptiness beneath, often triggered by major life failures or loss of supply. : severe depression, possibly psychotic-level denial of reality, substance abuse, or suicide. The person who seemed supremely confident becomes shattered, because confidence was performance requiring stage and audience that aging has removed.

The Pathological Aging Narcissist

Some narcissists respond to aging’s threats by becoming increasingly pathological. Unable to accept normal aging, they make themselves and everyone around them miserable.

Compensating for lost power, some become controlling and demanding of family. Adult children become trapped caring for a parent who still tries to dominate them. The aging narcissist weaponises their decline: “After all I’ve done for you, this is how you treat me?” Others reframe aging as injustice perpetrated against them. Every limitation, every loss, every change proves the world’s unfairness. They collect grievances, maintain bitter inventory of slights, and cultivate identity as tragic figure mistreated by fate.

Unable to accept reality, some construct elaborate denial. They may claim to be younger than they are, insist they could still do things they clearly cannot, or maintain grandiose narratives about their position in the world that others find painful to witness. Having burned through relationships across their lifetime, many face old age alone. Insight never comes. They maintain the same patterns that caused the isolation: blaming others, feeling entitled to attention they no longer receive, dying lonely while insisting they chose solitude.

Suicide Risk: The Ultimate Escape

Narcissism and Suicidality

Narcissists’ grandiosity might seem protective—their inflated self-regard could buffer against the hopelessness driving suicide. Yet research demonstrates that narcissism significantly increases suicide risk, particularly when narcissistic supplies collapse. 993 The risk is greatest for those experiencing Narcissistic Collapse Narcissistic Collapse A severe breakdown of the narcissist's false self defences, exposing the shame and emptiness beneath, often triggered by major life failures or loss of supply. .

Grandiose narcissists, while potentially engaging in risky behaviours with lethal consequences, show lower rates of suicidal ideation. Vulnerable narcissists—those with overt grandiosity but underlying fragility—show significantly elevated suicide risk approaching rates seen in Borderline Personality Disorder Borderline Personality Disorder A personality disorder characterized by emotional instability, intense fear of abandonment, unstable relationships, and identity disturbance. Often develops from childhood trauma and shares overlaps with narcissistic abuse effects. . 259

The standard classification misses a key dynamic: even grandiose narcissists become vulnerable when supply fails. The aging narcissist, the narcissist whose career implodes, the narcissist abandoned by their partner, the narcissist facing public humiliation—these individuals experience narcissistic collapse that can precipitate suicidal crisis.

Dr Adaora Obi, a psychiatrist who runs a crisis intervention unit, describes a pattern she sees regularly. “They come in after some kind of exposure. Financial fraud discovered. Affair made public. Fired for cause. And they’re not presenting like typical suicidal patients. No tearfulness, no hopelessness in the usual sense. They’re angry. They talk about being betrayed, about the unfairness, about the people who did this to them.” The suicidal ideation often emerges indirectly. “They’ll say something like, ‘They’ll be sorry when I’m gone,’ or ‘I’ll show them.’ The suicide isn’t about escaping pain—it’s about punishing. Or controlling.” She describes a patient, a former executive, who made a serious attempt after his company’s board removed him. “In the hospital afterward, he wasn’t relieved to be alive. He was furious it hadn’t worked. Said we’d ‘ruined’ his exit. Those were his words. His exit.” She’s careful to note: “The suffering is real. The emptiness is real. But the expression looks different. If you’re assessing for standard depressive suicidality, you’ll miss it.”

The Narcissistic Motive for Suicide

When narcissists become suicidal, the underlying motivation differs from other populations. Depression-driven suicide stems from pain and hopelessness; impulsive suicide from acute Emotional Dysregulation Emotional Dysregulation Difficulty managing emotional responses—experiencing emotions as overwhelming, having trouble calming down, or oscillating between emotional flooding and numbing. A core feature of trauma responses and certain personality disorders. ; psychotic suicide from delusional beliefs. Narcissistic suicide follows its own logic. 791

Some narcissistic suicide represents ultimate rage attack. Unable to destroy those who failed to provide supply, the narcissist destroys themselves, but frames it as the ultimate punishment for those left behind. “Now you’ll see what you’ve done.” “This is your fault.” “You’ll regret this forever.” The suicide becomes weapon wielded even in death. When facing public exposure of their failures or crimes, others choose death over shame. The convicted financier who kills himself before sentencing, the disgraced politician who dies rather than face scandal, the exposed narcissist who cannot tolerate others knowing they are not the person they claimed to be. Death offers escape from unbearable shame.

For some, suicide becomes ultimate dramatic gesture. They script their death as tragic culmination of heroic life, as martyrdom, or as statement that will ensure they are remembered. The suicide note explaining their philosophical reasons, the public method ensuring attention, the timing designed for maximum impact—death becomes final performance. After a lifetime maintaining the false self, some aging narcissists simply become exhausted. The effort of constant performance, the emptiness that supply never filled, the accumulation of failed relationships and bridges burned—facing years of continued emptiness becomes intolerable. They recognise that their life has always been empty and will remain so.

The ultimate Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. is loss of control. Terminal illness, dementia, or other conditions threatening autonomy represent intolerable loss. Some narcissists choose suicide to maintain control over their ending, preferring self-determined death to the indignity of decline they cannot manage.

Warning Signs Specific to Narcissists

Standard suicide risk assessment misses narcissism-specific warning signs because they look different from typical suicidal presentations.

Rather than appearing depressed, the at-risk narcissist may become more grandiose. They speak about their death in elevated terms, describe how their absence will devastate others, or frame potential suicide as noble or meaningful. This grandiosity masks suicidal planning. Increased vindictiveness, revenge fantasies, or statements about making others pay can signal risk. The narcissist contemplating suicide as revenge may become more focused on those they blame.

The suicidal narcissist may engage in seemingly benevolent behaviours: giving away possessions, making peace with enemies, or completing final projects. But these may be wrapping up affairs before death rather than genuine reconciliation. When the individual faces exposure—criminal charges, public scandal, professional disgrace, relationship exposure—risk increases dramatically. The period immediately after humiliation is particularly dangerous, before new defences form.

Loss of primary supply sources—divorce, job loss, children going no contact, public failure—creates crisis. Without supply, the narcissist confronts the emptiness they have spent their life avoiding. If they cannot quickly establish new sources, suicidal ideation can emerge rapidly. The narcissist’s isolation differs from depression’s social withdrawal. They may be alone but insist it is their choice, that others do not deserve them. However, if this narrative fails and they recognise their isolation as a consequence of their behaviour, suicidal risk increases.

The Imitation Suicide Phenomenon

One disturbing aspect of narcissistic suicide is the potential for it to inspire others. When celebrities or public figures with narcissistic features die by suicide, particularly if their death receives attention and sympathy, vulnerable individuals may identify with the narrative. 915

The narcissistic framing—“My pain was too great,” “The world couldn’t appreciate me,” “My death will show them”—can appeal to others struggling with narcissistic injury. Social media amplifies this effect, with posthumous lionisation and romantic narratives about the deceased’s suffering. For vulnerable narcissists watching, this provides a template and validation for their own suicidal ideation.

Responsible reporting and discussion of narcissistic suicide matters—neither romanticising it nor presenting it as heroic or meaningful, but acknowledging the tragedy while avoiding glorification that could inspire imitation.

Prevention and Intervention Challenges

Suicide prevention with narcissistic individuals proves particularly challenging.

Narcissists rarely admit to suicidal thoughts because doing so would acknowledge weakness. They may deny risk even when clearly at risk, making assessment difficult. Some narcissists use suicide threats as manipulation: to prevent partner from leaving, to gain attention, or to control others. A “boy who cried wolf” dynamic may follow, where actual risk is dismissed after numerous false alarms.

While most suicide involves warning signs and planning period, narcissistic suicide can occur more impulsively in response to acute narcissistic injury. The time between humiliation and attempt may be very brief, providing limited intervention window. Traditional suicide prevention—hospitalisation, intensive outpatient treatment, medication—requires accepting help, which challenges narcissistic self-sufficiency. Narcissists may refuse intervention or appear to comply while secretly planning suicide.

When narcissists attempt suicide, they tend to use more lethal methods. 791 This may reflect genuine intent to die (not calling for help) or narcissistic need to ensure the act is taken seriously. Either way, survival rates are lower.

The most effective intervention addresses the narcissistic injury directly: restoring some source of supply, helping rebuild the false self temporarily, or validating the grandiose self rather than challenging it. This is crisis management, focused on immediate safety rather than personality change.

Failed Relationships Pattern: Inevitable Repetition

The Narcissistic Relationship Cycle

From the victim’s perspective (Chapter ), the cycle begins with idealisation that feels like finally being seen, then devaluation that shatters reality, then manipulation that makes escape difficult. What does it look like from inside the narcissist?

The four-stage cycle: idealisation, devaluation, sustained manipulation, discard—feels entirely different to them. 99 During idealisation, the narcissist genuinely experiences excitement and hope. Perhaps this person will finally fill the emptiness. They believe their own performance, briefly experiencing the false self as real. When devaluation begins, they experience the partner’s inevitable imperfection as betrayal: “I thought you were special.” The manipulation tactics, gaslighting (Chapter ), triangulation, intermittent reinforcement (Chapter )—serve unconscious functions the narcissist does not recognise. When relationships end, they never see their role in the pattern.

Why Patterns Repeat

The narcissist’s relationships fail in predictably similar ways across decades.

Every partner eventually depletes as a source of validation. Familiarity reduces supply potency: the partner who once gazed adoringly now sees clearly. This feels like the partner has changed, when actually the narcissist’s need has increased while supply has normalised. As relationships deepen, authentic intimacy threatens to expose the true self. The narcissist maintains distance that prevents genuine connection. The child who learned that being truly seen meant being rejected grows into an adult who ensures no one ever sees them clearly again.

The narcissist projects emptiness onto partners while requiring perfect mirroring no real person can maintain. Every partner’s inevitable failures become fundamental flaws requiring devaluation. Most people learn from relationship failures. The narcissist cannot because acknowledging their role would trigger shame. They repeat patterns with different partners, always certain the partner is the problem.

The Accumulation of Damage

Each failed relationship leaves debris: damaged partners, confused children, betrayed friends. By middle age, the narcissist may have multiple ex-partners, estranged children, and a reputation as difficult, but they lack insight into the pattern. The common denominator remains invisible.

The intergenerational damage perpetuates. Children of narcissists (Chapter ) carry attachment wounds into adult relationships, sometimes choosing narcissistic partners because that is what love looks like. The cycle continues until someone finds the strength to break it.

The Aging Narcissist’s Relationships

By later life, relationship consequences become inescapable. Adult children often choose limited or no contact. Some narcissists continue pursuing younger partners; others find themselves with a trapped caregiver—an adult child bound by duty to care for someone who never adequately cared for them. Many are utterly alone but maintain the narrative that this was their choice, dying while insisting on their superiority.

Professional Implosions: The Career Arc

Success Through Narcissistic Traits

The same traits that corrupt organisations (see Chapter on corporate narcissism) can build careers, at least initially. 192 Grandiosity manifests as confidence; charm facilitates networking; empathy deficits enable ruthless decisions; supply-seeking translates to ambition. The narcissist interviews well, pursues opportunities aggressively, takes credit readily. Sales, entertainment, politics, law, entrepreneurship—many fields reward these traits, for a time.

Early success reinforces grandiosity. The narcissist attributes achievements to exceptional nature, ignoring luck or others’ contributions, failing to recognise that sustained success requires collaboration and adaptation they struggle to maintain.

Why Careers Eventually Fail

The same traits that facilitate early success eventually create professional problems. As careers advance, success increasingly depends on collaboration and delegation—the narcissist who succeeded individually now struggles with interdependence, hoarding credit, resisting delegation, alienating colleagues. The grandiose narcissist believes they already know everything important, resisting feedback while younger colleagues learn new methods. Conflicts accumulate until even excellent performance does not outweigh interpersonal damage. And entitlement leads to ethical violations: they believe rules apply to others, not to exceptional them.

By mid-life, many narcissists experience career crisis. The executive passed over for promotion becomes bitter, convinced of conspiracy, unable to see that interpersonal deficits forged the problem. The entrepreneur who succeeded once pursues vanity projects, ignoring market research because their intuition is superior. The professional facing ethical charges experiences martyrdom rather than accountability. The expert whose field evolved refuses to adapt, becoming irrelevant while insisting the field has declined.

Some implosions become spectacle. Bernie Madoff, Elizabeth Holmes, and similar figures exemplify the pattern: grandiose vision, willingness to deceive, inability to admit failure, escalating fraud to maintain appearances. 777 Steve Jobs nearly destroyed Apple through narcissistic management before his forced departure, though he later learned from this experience. Narcissistic politicians’ hubris (Chapter ) leads to spectacular falls: corruption, sexual scandals, abuse of power. Believing themselves untouchable, they take risks that reveal character.

The Aftermath

Professional implosion forces confrontation with reality the narcissist has avoided. Most maintain delusional narrative: they were sabotaged, betrayed, ahead of their time. Some decompensate without professional identity and supply—the career was the false self’s primary scaffold, and without it, nothing remains. Others move to new fields or locations, attempting to repeat former success; they may succeed briefly, but the same patterns emerge, each iteration less successful as references accumulate and age reduces opportunities.

Very occasionally, professional failure generates a crack in defences large enough for insight. The humiliation is so complete that denial becomes impossible. With skilled therapeutic support, some narcissists use this crisis for genuine change. But this remains rare—the psychological barriers to insight persist even in crisis.

End-of-Life Reckoning: Facing the Unlived Life

The Loneliness of the Aging Narcissist

A lifetime spent protecting the false self, destroying relationships, burning bridges, and refusing vulnerability finally accumulates into inescapable consequence. The aging narcissist faces a reckoning that no grandiose defence can prevent: mortality approaches, and they realise they have never truly lived.

Developmental psychologist Erik Erikson described the final psychosocial crisis as integrity versus despair: the need to review one’s life and find it meaningful versus experiencing regret and hopelessness. 360 For the narcissist, this review proves devastating. The criteria for integrity—authentic relationships, generative contributions, acceptance of one’s life as it was lived—require capacities the narcissist never developed.

Walter, eighty-one, sits in the day room of an assisted living facility. He was a property developer, once owned half the commercial real estate in his city. “They put me in here,” he says, meaning his son and daughter-in-law. “After everything I built.” He has photographs in his room: buildings, ribbon cuttings, handshakes with mayors. No family pictures. His son visits monthly, stays an hour, leaves looking exhausted. “He doesn’t understand business,” Walter says. “Never did. Soft, like his mother.” His wife died eleven years ago. He speaks of her dismissively: “She was never happy. Nothing was ever enough.” The staff find him difficult. He berates the aides, accuses them of stealing, demands to speak to supervisors. One afternoon, a researcher interviewing residents about life satisfaction finds him staring at the wall. “I had a dream about my daughter,” he says. His daughter went no-contact fifteen years ago after what Walter calls “a misunderstanding about money.” In the dream, she was a child again. “She was asking me something. I couldn’t hear what.” He trails off, then: “She was always too sensitive. Like her mother.” He asks when lunch is served, complains about the food.

They have had many relationships—romantic partners, friends, colleagues—but no genuine intimacy. No one truly knew them because they never revealed their authentic self. The people they pushed away or destroyed outnumber those who remained. They are surrounded by acquaintances or alone, but either way, experiencing profound social isolation. The accomplishments that once provided supply no longer satisfy. Awards gather dust. Old successes become dated. The recognition they craved proves ephemeral—people move on, care about current achievements, forget past glories. The narcissist discovers that external validation cannot provide lasting meaning.

Decades devoted to maintaining the false self—the energy, the calculation, the constant performance. What if they had spent that energy building real connections? Pursuing authentic interests? Developing genuine competence? The life they might have lived haunts the life they performed. In rare moments of clarity, some aging narcissists glimpse the harm they caused. Spouses emotionally destroyed. Children traumatised. Colleagues undermined. Friends betrayed. The grandiose narrative framed these as necessary or justified, but aging brings uncomfortable awareness: they hurt people. Many people. Often deliberately.

Most painful is recognising the authentic self that was never allowed to exist. Who might they have been without the narcissistic defences? What connections might they have formed? What joy might they have experienced? They protected against shame by constructing the false self, but the cost was their actual life.

Mortality Terror

Death exemplifies the ultimate narcissistic injury. The grandiose self cannot accept its own termination. The narcissist has spent their life believing themselves exceptional, deserving of special treatment, somehow different from ordinary mortals. Death reveals this as delusion. 653

The aging narcissist becomes fixated on legacy—ensuring they are remembered, controlling their posthumous reputation, creating monuments to themselves. They may write memoirs presenting grandiose distorted history, establish charitable foundations bearing their name, or pressure children to carry on their work. The goal: immortality through memory. Even legacy rings hollow. Being remembered after death does not address the emptiness experienced while living. And the narcissist may dimly recognise that their actual legacy—damaged relationships, harmed people, destructive behaviours—differs from the one they attempt to construct.

Some aging narcissists direct rage at the universe for subjecting them to aging and death. They may refuse medical treatment (denying illness), pursue desperate anti-aging interventions, or become increasingly bitter about mortality’s democratic nature. The rage masks terror: if death comes for them like everyone else, they were never special at all. When defensive grandiosity fails, some narcissists experience utter nihilism. If they are not special, nothing matters. If death erases everyone, achievement is meaningless. The worldview organised around their own centrality collapses, leaving philosophical void. Life feels pointless because only their life mattered, and their life is ending.

The aging narcissist may make increasingly desperate attempts to recapture youth or relevance. Age-inappropriate behaviour, pursuits of much younger partners, risky ventures attempting to prove vitality, grandiose claims about future plans—all represent frantic defence against mortality awareness.

The Deathbed Dilemma

Facing actual death, the narcissist encounters an impossible choice: maintain the false self to the end, or risk authentic vulnerability in final moments. Most choose the familiar defence, foreclosing possibilities for meaningful closure.

Many narcissists die as they lived: grandiose, defended, isolated. They maintain the narrative of their superiority even as they are dying. They refuse to acknowledge fear or sadness. They may continue manipulating or controlling those around them. They die alone in the psychological sense even if physically attended, because they never lowered defences enough for authentic connection.

Family members hoping for deathbed reconciliation typically experience disappointment. The narcissistic parent does not apologise for past abuse. The narcissistic spouse does not acknowledge their behaviour. Instead, they maintain grievances, make demands, or blame others to the end. The chance for genuine closure is lost to defensive grandiosity.

Rarely, impending death cracks defences enough for authentic moment. The narcissist may express regret, acknowledge fear, or reach for genuine connection. But even these moments remain complicated. Are they genuinely vulnerable or performing vulnerability? Do they understand what they are apologising for? Can they tolerate the response if forgiveness is not immediately granted? For families, these moments are precious but insufficient. One authentic interaction cannot undo decades of abuse. The dying narcissist may feel they have made amends, while survivors recognise these last-minute gestures do not constitute genuine reconciliation or healing.

Some dying narcissists experience brief terrible clarity: they wasted their life. The performance was unnecessary. The defences protected against imagined dangers while creating real ones. They traded authentic living for defended existence, and now it is too late. This recognition compounds the suffering—seeing clearly, while dying, that one’s life was spent in defence rather than engagement.

The Survivors’ Complex Grief

A narcissist’s death creates particular challenges for survivors. Unlike mourning someone who loved and was loved in return, survivors face complicated grief mixing relief, guilt, unresolved anger, and ambiguous loss.

Many survivors feel relief when the narcissist dies—relief from manipulation, from anxiety, from obligation. But this relief generates guilt: should not they feel sad? Society expects bereavement, not relief. Survivors may hide their actual feelings, performing grief they do not feel, generating internal cognitive dissonance. The narcissist’s death forecloses possibilities for resolution. The survivor who hoped for apology or reconciliation will never receive it. The anger remains unaddressed, with no target for expression. Some survivors feel cheated that the narcissist escaped accountability by dying.

Survivors may experience the narcissist as having been psychologically absent even when physically present. The death makes official what was always true: this person was never emotionally available. Grieving someone who was never really there proves confusing—what exactly is being mourned? Family and social conventions often pressure survivors to idealise the deceased. “Don’t speak ill of the dead.” The narcissist’s grandiose narrative may be enshrined posthumously, erasing their actual impact. Survivors forced to participate in this distortion experience further invalidation.

The narcissist’s death may free survivors to live authentically: establish boundaries, pursue goals the narcissist opposed, or simply exist without fear of judgement. This freedom is a genuine gift. But it is mixed with sadness—sadness that freedom required death, sadness that a real relationship was never possible, sadness about the parent/partner/sibling who might have been but never was.

What Might Have Been

The aging narcissist confronts what might have been. If the narcissistic defences represent protection against childhood wounds, what would life have looked like with different defences—or with actual healing?

Without narcissistic defences, they might have formed genuine intimate connections—mutual partnerships where both people were known and valued, friendships based on authentic sharing rather than strategic supply extraction, parenting that created secure attachment rather than trauma. The energy devoted to grandiose performance might have created genuine mastery. Instead of claiming expertise while remaining superficial, they might have developed deep competence. Instead of taking credit, they might have done work worthy of recognition. The accomplishments would have satisfied because earned through authentic effort.

Without spending a lifetime fleeing their authentic self, they might have developed genuine self-awareness. They might have discovered actual interests and capabilities rather than constructing preferences designed to impress. They might have known who they were. Erikson’s concept of generativity—contributing to the next generation, mentoring, creating lasting value—might have been possible. Instead of extracting from others to feed the false self, they might have given meaningfully. Their legacy might have been positive impact rather than damaged people.

Perhaps most importantly, they might have experienced peace. The constant vigilance required to maintain the false self creates perpetual anxiety. Without this burden, they might have known contentment—simple satisfaction with being themselves, whoever that might be, beyond grandiose triumph.

The aging or dying narcissist sometimes glimpses these alternatives in a devastating moment of clarity. The life they might have lived exists as ghostly parallel to the life they performed. This recognition, when it occurs, brings grief that cannot be resolved: grief for the self they never allowed to exist, for the relationships they never formed, for the life they never lived.

Conclusion: The Defended Life

The narcissist’s pain differs in kind from their victims’: it is self-inflicted and self-perpetuating. The narcissistic defences that protect against early wounds become the very mechanisms that ensure continued suffering. The false self that shields against shame prevents authentic connection that might provide genuine worth. The grandiosity that compensates for emptiness requires behaviours that create more emptiness. The narcissist is trapped in a prison of their own construction, unable to escape because escape would require acknowledging the prison’s existence.

The narcissist’s internal experience unfolds through chronic emptiness that no amount of supply fills, shame so toxic it must be defended against at all costs, fragmented identity lacking a coherent self, an aging process that strips away compensatory mechanisms, accumulating failures as patterns repeat, and finally an end-of-life reckoning when the false self fails and the unlived life becomes visible.

This suffering does not excuse narcissistic behaviour. The damage narcissists inflict on others—partners gaslit to doubt their sanity, children traumatised by emotional absence, colleagues undermined, organisations corrupted—remains real and inexcusable regardless of the narcissist’s internal experience. Victims’ suffering takes precedence in the moral calculus. Explaining narcissistic behaviour does not justify it.

Recognising that narcissism develops as defence against developmental wounds emphasises the importance of secure attachment, consistent validation, and unconditional love in childhood, precisely what narcissistic families fail to provide. Preventing narcissism means creating conditions where children develop genuine self-worth rather than compensatory grandiosity. The rare narcissists who seek treatment and achieve insight do so by gradually confronting defended-against material: shame, emptiness, authentic self. This clarifies why traditional approaches often fail: challenging the false self directly triggers overwhelming shame that reinforces defences.

Understanding the structural nature of narcissistic defences explains why change is so rare. The false self was not chosen consciously; it developed as survival mechanism. Expecting narcissists to suddenly gain insight or change at their core misunderstands the depth of the pathology. This helps victims stop hoping for changes that almost never occur. One can feel compassion for the narcissist’s internal suffering while maintaining firm boundaries against their harmful behaviours. Empathy need not mean tolerance of abuse.

The narcissist’s plight—spending life maintaining false self, never knowing authentic connection, dying without having truly lived—offers a cautionary tale. To varying degrees, many people sacrifice authenticity for social approval, trade genuine self-expression for strategic presentation, or confuse external validation with internal worth. The narcissist represents extreme endpoint of these universal temptations.

The hollowed self—empty, defended, isolated, dying without ever having been real—represents tragedy in the classical sense. Not a good person struck by misfortune, but a flawed person whose very defences ensure their suffering. The narcissist generates their own catastrophe through psychological mechanisms developed to prevent catastrophe. They create the loneliness they fear, the abandonment they expect, the worthlessness they deny.

Is this suffering deserved? The question misses the point. Suffering simply is. The child who developed narcissistic defences did not choose to be wounded. The adult maintaining those defences may not consciously understand what they are protecting against. The aging narcissist confronting the wasted life experiences pain regardless of whether we deem it justified.

That the suffering was preventable makes early intervention all the more urgent. With different early experiences, the narcissist might have developed authentic self-worth. With different defences, they might have formed real connections. With insight (however rare), they might have changed.

Understanding the narcissist’s internal experience—the emptiness, the fear of exposure, the inability to access authentic selfhood—contextualises their behaviour without excusing it. For those harmed by narcissists, this understanding may provide some closure: the cruelty was mechanical, serving internal functions independent of the actual person targeted.

The clinical picture presents a tension. Narcissists cause substantial harm and experience substantial suffering. Their behaviour warrants consequences and boundaries; their developmental history warrants recognition as tragedy. Prevention efforts benefit from acknowledging both dimensions—protection from narcissistic harm and reduction of conditions producing narcissistic development.

Most individuals with consolidated narcissistic personality organisation will not change. The defensive structure that causes suffering also prevents the capacity that change would require. This clinical reality informs realistic expectations for treatment and relationships.