Introduction: The Most Difficult Question

In forty years of clinical practice, Dr James Masterson saw thousands of personality disorder patients. He developed sophisticated treatment protocols for Borderline Personality Disorder Borderline Personality Disorder A personality disorder characterized by emotional instability, intense fear of abandonment, unstable relationships, and identity disturbance. Often develops from childhood trauma and shares overlaps with narcissistic abuse effects. , achieving impressive success rates. Yet when asked about treating Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) A mental health condition characterised by an inflated sense of self-importance, need for excessive admiration, and lack of empathy for others. , his response was stark: “They do not come to treatment, and if they do, they do not stay.” 818 This brutal honesty from one of personality disorder treatment’s pioneers captures the essential challenge: the very nature of narcissistic personality disorder creates resistance to the vulnerability, self-examination, and sustained engagement that effective treatment requires.

The question “Can Narcissus be healed?” demands honest engagement rather than therapeutic platitudes. Clinicians face pressure to offer hope to suffering families. Self-help authors sell transformation narratives. But the clinical literature tells a sobering story: narcissistic personality disorder remains among the most treatment-resistant conditions in psychology. Success rates are low, dropout rates are high, and even successful cases typically require years of therapy producing modest gains rather than fundamental transformation.

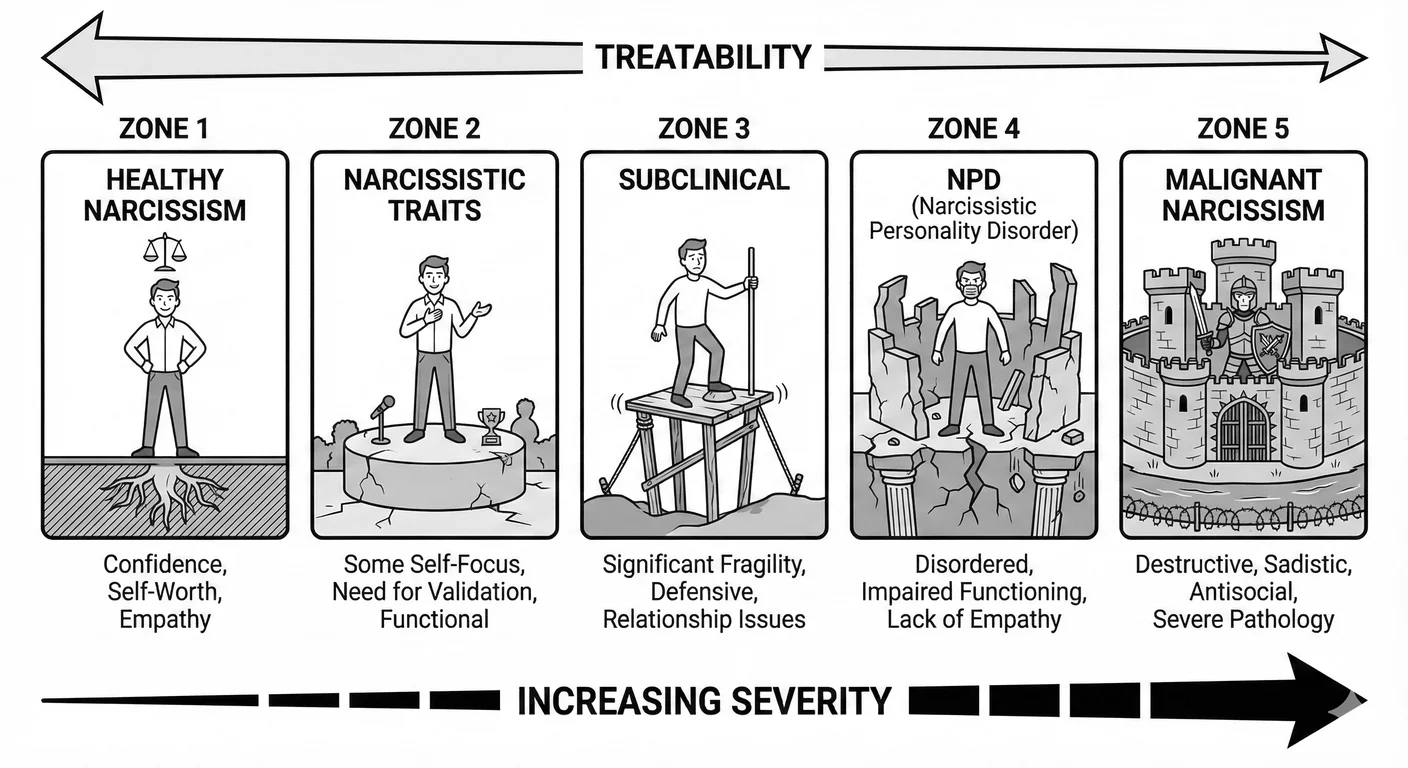

Some narcissists do change, though usually only under specific circumstances. Certain therapeutic approaches show more promise than others. Narcissism’s spectrum—from adaptive self-regard through narcissistic traits to full personality disorder—reveals that not all narcissism requires treatment and not all narcissism is equally intractable. Age, subtype, co-occurring conditions, and life circumstances all affect treatment prospects.

The stakes extend beyond individual suffering. Narcissism at epidemic scale fractures societies and damages everyone in proximity. If narcissism is untreatable, we face a grim future of managing rather than solving the problem. If even modest treatment progress is possible, this offers hope for individual lives and, potentially, cultural shift.

Why Narcissists Do Not Seek Treatment

The Grandiosity Barrier

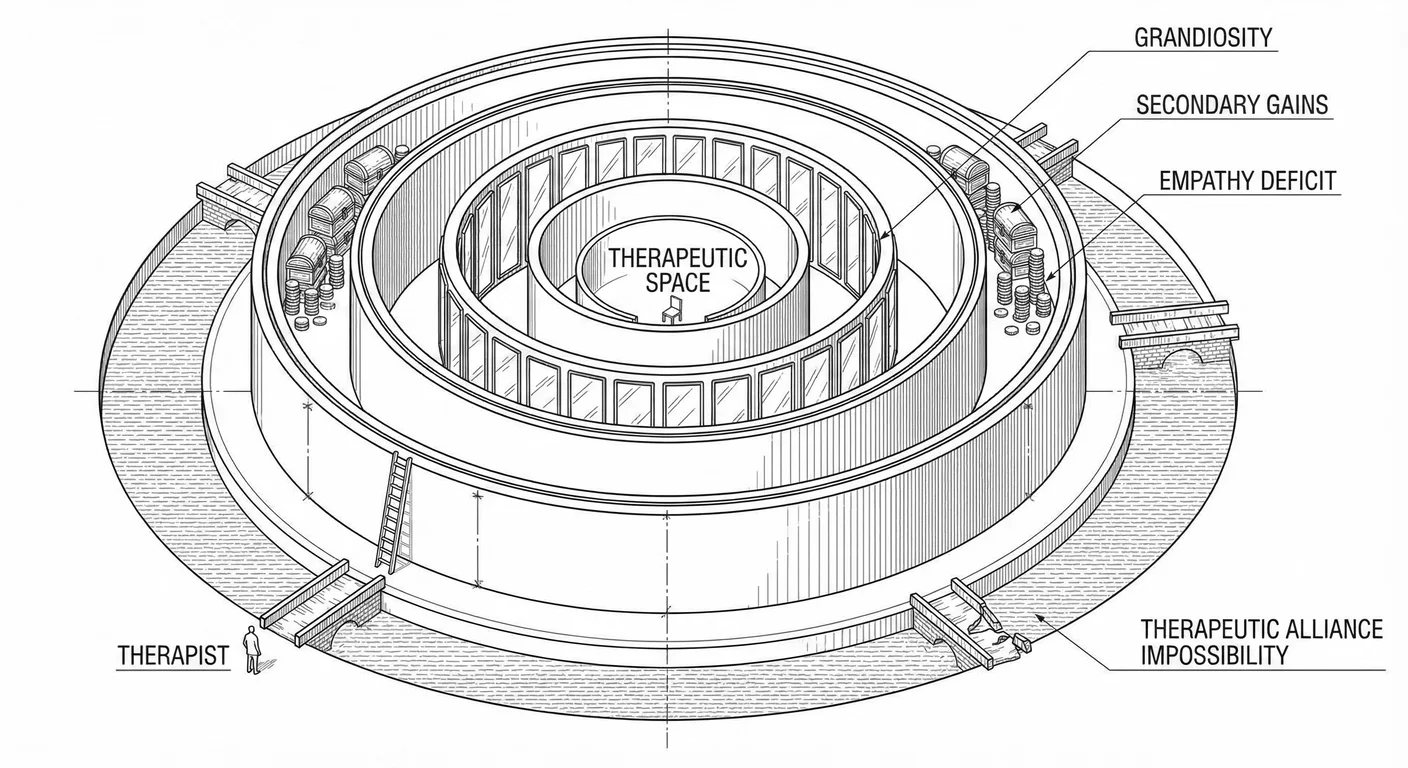

NPD’s core features prevent recognising that treatment is needed. Grandiosity, the inflated sense of superiority and specialness, makes the idea of needing help intolerable. In the narcissist’s worldview, problems exist in others, not self. They are exceptional; everyone else is deficient. Therapy is for weak, damaged people. The narcissist is neither.

This is “malignant self-regard”—a self-concept so grandiose and defended that it cannot accommodate the notion of having psychological problems 649 . When narcissists experience difficulties, they externalise blame. Relationship failures occur because partners are inadequate. Career setbacks happen because colleagues are jealous or superiors are incompetent. Legal troubles result from unfair persecution. The possibility that their own behaviour contributes never registers as a realistic possibility.

Clinical vignette: Ignatius, a Dutch surgeon, was referred to therapy by the hospital administration after multiple complaints about his treatment of nurses and residents, many of whom had started turning down shifts where there was even a hint he might be present. He arrived at his first session grumbling: “I don’t have problems; the hospital has a problem with excellence. They’ve grown accustomed to mediocrity and can’t handle someone who knows perfection is what you need to save the most people. My only mistake was accepting a position in such a small country that doesn’t appreciate my calibre.” When the therapist gently suggested that perhaps his communication style was worth examining, Ignatius became enraged: “Are you suggesting I’m the problem? You’re just like them; mediocrity dragging down excellence.” He stormed out.

Ignatius exemplifies the cartoonish, predictable grandiosity barrier. Behaviour change means admitting one was not perfect, that one is not perfect. The world has noticed. It sees how weak one is. The very suggestion threatens the false self-structure that provides his psychological survival. For Ignatius and others like him, therapy represents an existential threat, with potential help beside the point.

This defensive structure extends to how narcissists process feedback. Research shows narcissists respond to criticism with rage and counterattack rather than reflection—when told they performed poorly on a task, high-narcissism individuals became more confident in their performance and more hostile towards the evaluator 178 . They literally could not process negative feedback as information about themselves; it only registered as attack requiring retaliation.

Therapy fundamentally involves receiving feedback about oneself from another person. The therapist observes patterns, names dynamics, and offers interpretation—psychodynamic therapy’s core method. For the narcissist, this feels like sustained assault on the grandiose self. The automatic defensive response is to devalue the therapist, reject interpretations, and exit treatment. The very process designed to help triggers the defences preventing help.

projection

and Externalisation

Narcissists employ massive Projection Projection A psychological defence mechanism where narcissists attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or behaviours to others. , attributing their own unacceptable qualities to others. Problems always exist externally in this distorted perception. The narcissist feels empty inside but perceives others as hollow. The narcissist lacks Empathy Empathy The capacity to understand and share another person's feelings, comprising both cognitive (understanding) and affective (feeling) components—often impaired in narcissism. but accuses others of being cold. The narcissist manipulates but experiences others as manipulative. This projective defence makes recognising one’s own patterns nearly impossible.

Through projection, narcissists construct entire paranoid worldviews, populating their world with envious, hostile, manipulative people—because these are their own disowned qualities 14 . Relationships become zero-sum competitions because that is how they approach connection. Others’ success feels like personal attack because their own success depends on others’ failure. This projected reality becomes so convincing that alternative perspectives seem absurd.

You have likely witnessed this if you have ever tried to give a narcissist feedback. The colleague who micromanages everyone accuses you of being controlling. The friend who dominates every conversation complains that no one listens to her. The partner who lies constantly becomes obsessed with catching you in deception. Their own behaviour becomes invisible to them—they perceive only its mirror image in others.

Therapy becomes nearly impossible under these conditions: the person needing to change cannot see what needs changing because it has been projected onto everyone else.

Externalisation creates parallel problems. Rather than experiencing internal conflict—“I behaved badly and feel guilt”—the narcissist externalises: “They made me behave that way.” This preserves the grandiose self at the cost of agency and accountability. But it also eliminates motivation for change. If others’ inadequacies cause the problems, why would the narcissist need to change? The solution, from their perspective, is obvious: change everyone else.

The Empathy Deficit Paradox

The empathy deficit itself significantly blocks treatment. Successful therapy requires capacity to take the therapist’s perspective, imagine how one’s behaviour affects others, and feel motivated to change through identification with others’ suffering. Narcissists lack exactly these capacities. They cannot fully grasp the therapist’s viewpoint, do not register how their behaviour affects others, and feel unmoved by others’ distress.

A cruel paradox follows: the trait most needing treatment—empathy deficit—prevents the relationship necessary for treatment. The therapist offers concerned observations; the narcissist hears inexplicable criticism. The therapist provides helpful feedback; the narcissist finds it irrelevant. The therapist connects the narcissist’s behaviour to others’ pain; the narcissist wonders why others’ pain should matter. Empathic reflections about feelings miss the mark because the narcissist does not have access to genuine feelings behind the False Self False Self A defensive psychological construct that narcissists create to protect themselves from shame and project an image of perfection, superiority, and invulnerability. .

How do you help someone who cannot feel what you feel?

Neuroscience research demonstrates that narcissists show reduced activation in brain regions associated with empathy when viewing others in distress, literally not feeling others’ pain in the automatic, visceral way that motivates prosocial behaviour 370 . When you see someone stub their toe, you wince. When a narcissist sees someone stub their toe, the neural circuits that would make you wince stay quiet. This neurological reality creates a practical therapeutic challenge: how do you motivate someone to change when they do not feel bad about hurting others?

Traditional therapeutic approaches assume some capacity for empathic connection. Psychodynamic therapy uses the therapeutic relationship as change agent. Cognitive therapy relies on ability to imagine others’ perspectives. Humanistic approaches depend on the client’s genuine self emerging. But when the client fundamentally lacks empathy, these approaches founder. The therapist’s warm regard registers as weakness to exploit. Perspective-taking exercises feel pointless. The “genuine self” beneath defences may not exist in any accessible form.

Secondary Gains of Narcissism

Unlike many psychological disorders that produce only suffering, narcissism often delivers real benefits, at least in the short term—and for the narcissist if not those around them. Why would Ignatius the surgeon give up his narcissism when it contributes to professional success and social admiration (at least from those who do not know him well)?

Robert Hare’s work on psychopathy revealed similar dynamics—many psychopathic individuals function successfully in business and politics precisely because their lack of empathy enables ruthless decision-making 520 . Narcissism operates similarly. The inability to feel others’ distress enables exploitation. The grandiose self-concept produces confidence attractive to others. The lack of genuine intimacy prevents vulnerability to emotional pain. The willingness to self-promote creates visibility and opportunity.

Nancy McWilliams describes narcissistic character as “adaptive” in contemporary culture, noting that where previous eras valued humility, current culture celebrates self-promotion 840 . Where community once constrained individual ambition, now “authenticity” means expressing wants without compromise. Where shame once enforced social norms, now we consider shame a toxic limitation on self-actualisation. In this environment, narcissistic traits produce success, not dysfunction.

This cultural shift significantly affects treatment motivation. When narcissistic behaviour is rewarded by the environment, why change? The narcissistic CEO receives massive compensation and media adulation. The narcissistic influencer gains millions of followers. The narcissistic politician wins elections. From the narcissist’s perspective, therapy represents obstacle to success, with problem-solving irrelevant. Any suffering they experience comes from others failing to provide adequate Narcissistic Supply Narcissistic Supply The attention, admiration, emotional reactions, and validation that narcissists require from others to maintain their fragile sense of self-worth. , not from their own character pathology.

Even when narcissism creates problems, these typically manifest as others’ suffering rather than the narcissist’s. The narcissistic parent damages children, but the parent does not feel this damage. The narcissistic partner destroys relationships but moves on to new supply without remorse. The narcissistic boss creates a toxic workplace but receives bonuses for “strong leadership”. Why would someone seek treatment for problems they do not experience and whose solutions would cost them benefits?

Therapeutic Alliance Impossibility

Effective psychotherapy depends on the therapeutic relationship—a collaborative, trusting relationship between therapist and client working towards shared goals. Decades of research establish that therapeutic alliance predicts treatment outcome better than specific techniques employed 572 . Narcissistic personality disorder makes authentic therapeutic alliance nearly impossible to establish.

Alliance requires capacities narcissists lack: trusting another person with vulnerability, tolerating being in a one-down position as help-seeker, and working collaboratively towards goals.

Trust requires risking vulnerability with someone who might hurt you. But narcissists view vulnerability as weakness and others as potential exploiters. They cannot risk genuine openness because any revealed weakness might be used against them (as they would use others’ weaknesses). The therapeutic engagement stays superficial: narcissists perform rather than reveal. They tell impressive stories, demonstrate verbal cleverness, and manage impressions, but never show the wounded person beneath the false self.

The therapeutic relationship’s asymmetry—therapist as helper, client as help-seeker—violates narcissistic need for superiority. Narcissistic patients spend sessions trying to impress therapists, demonstrate superior knowledge, or position therapists as inadequate 1048 . One patient spent months trying to prove he understood psychology better than his PhD therapist. Another began every session recounting accomplishments, seemingly unaware that he was there to address problems rather than receive applause.

Narcissists also cannot maintain stable positive regard through therapy’s inevitable challenges. When therapists confront defences, set Boundaries Boundaries Personal limits that define what behaviour you will and won't accept from others, essential for protecting yourself from narcissistic abuse. , or refuse to collude with grandiosity, narcissists experience this as betrayal and attack. They split, moving from Idealization Idealization A psychological defence where someone is perceived as perfect, all-good, and without flaws—the first phase of the narcissistic abuse cycle. to Devaluation Devaluation The phase in narcissistic relationships where the victim is criticised, belittled, and degraded after the initial idealization period ends. without middle ground. The therapist shifts from “brilliant expert who finally understands me” to “incompetent quack who is part of the conspiracy against me.” Sustained therapeutic work becomes impossible.

The Spectrum of Self-Regard

Healthy Narcissism: The Developmental Achievement

Heinz Kohut recognised that some narcissism—in the sense of grounded self-esteem and assertiveness—is not only normal but essential for psychological health 674 . Healthy narcissism provides realistic self-esteem independent of others’ validation, appropriate ambition and goal-pursuit, pleasure in one’s abilities and accomplishments, capacity for pride without grandiosity, resilience in the face of criticism or failure, and ability to admire others without envy.

Healthy narcissism develops through what Kohut termed “optimal frustration”—parents who mirror the child’s emerging self sufficiently to confirm existence and value, but not so completely as to prevent development of autonomous self-soothing. The child experiences: “I am seen and valued by my caregivers” (mirroring); “My caregivers are powerful and I am part of them” (idealising); and “I am similar to others like me” (twinship). These experiences, when provided in developmentally appropriate doses, create stable self-regard.

Healthy narcissism serves the self while remaining connected to reality and others. The person with healthy narcissism feels good about achievements that are real, not fantasised. They enjoy admiration but do not require constant validation for psychological survival. They can acknowledge flaws without experiencing catastrophic shame. They experience genuine joy in others’ successes rather than envy. Their self-esteem is resilient, buffeted by criticism but not destroyed by it.

You know people with healthy narcissism. The colleague who takes genuine pride in a project well done, accepts compliments gracefully, and celebrates when someone else gets promoted. The friend who pursues ambitious goals but adjusts when reality intervenes. The parent who delights in their children’s achievements without needing those achievements to reflect on themselves. These people have strong egos in the best sense: confident without being arrogant, ambitious without being ruthless, self-assured without being defensive.

Research distinguishes “authentic pride” from “hubristic pride”—authentic pride follows genuine achievement through effort (“I worked hard and succeeded”) 1235 . It motivates continued achievement and prosocial behaviour. Hubristic pride arises from inflated self-regard independent of achievement (“I’m superior to others by nature”). It motivates antisocial behaviour and creates interpersonal problems. Healthy narcissism produces authentic pride; pathological narcissism produces hubristic pride.

Narcissistic Traits: The Subclinical Middle

Between healthy narcissism and personality disorder lies a large population—arguably the majority—with narcissistic traits falling short of diagnostic threshold. These individuals show some narcissistic features (self-centreedness, need for admiration, sense of specialness) but not the pervasive pattern of grandiosity, empathy deficit, and interpersonal exploitation meeting NPD criteria. This middle zone represents most people clinicians encounter who have “narcissistic issues.”

DSM-5’s dimensional approach to personality disorders (in Section III) recognises this spectrum. Rather than present/absent diagnosis, personality pathology exists on continuum from absent through trait level to disorder level. Someone might score high on narcissistic grandiosity but low on empathy deficits. Another might show strong entitlement but maintain stable relationships. These subclinical narcissistic traits create problems less severe than full NPD but still requiring clinical attention.

People with narcissistic traits typically have some insight into their patterns. Unlike those with NPD, they can recognise when their self-centreedness causes problems. They may feel bad (if only instrumentally) about hurting others. They can, with effort, take others’ perspectives. Their self-esteem, while requiring more validation than optimal, does not completely fragment under criticism. These capacities make them much more treatable than those with full personality disorder.

You know people with narcissistic traits too. The friend who somehow steers every conversation back to themselves, but apologises when you point it out. The manager who needs more credit than warranted but can still acknowledge team contributions when prompted. The family member who sulks when not the centre of attention at gatherings but genuinely loves you underneath. These people are difficult but not destructive. They can hear feedback, even if they do not like it. They maintain long-term friendships, even if those friendships are sometimes exhausting. They are capable of love, even if that love is more conditional than ideal.

Paul Wink distinguished “overt” from “covert” narcissistic traits—overt traits include exhibitionism and grandiosity, the classic narcissistic presentation 1330 . Covert traits include hypersensitivity and feelings of inadequacy—narcissism hidden behind apparent humility. Both create problems, but covert narcissistic traits may bring more suffering to the narcissist themselves, creating greater treatment motivation.

Life circumstances often determine whether narcissistic traits remain subclinical or develop into disorder. A person with narcissistic traits might function well in a supportive environment providing adequate validation—admiring partner, successful career, attractive appearance. But the same person might decompensate under stress when validation dries up: romantic rejection, career failure, aging. The traits were always present; circumstances determined whether they became problematic.

Pathological Narcissism: The Personality Disorder

Full narcissistic personality disorder exemplifies the severe end of the spectrum. Here, narcissistic traits form pervasive patterns affecting all life domains, going beyond occasional problems. The grandiosity is rigid and defended, the empathy deficit severe, the interpersonal exploitation consistent. Most critically, there is no observing ego—no part of the person capable of stepping back and recognising the pattern.

If you have encountered someone with full NPD, the experience is unmistakable even if you lacked vocabulary for it. The boss who takes credit for every success and blames subordinates for every failure—not occasionally, but as a consistent pattern spanning years. The ex-partner who rewrote relationship history so completely that mutual friends questioned your sanity. The parent whose every interaction left you feeling smaller, crazier, more uncertain of your own perceptions. These individuals do not merely have difficult personalities; they leave wreckage. Their former partners need therapy. Their adult children struggle with trust. Their colleagues eventually learn to document everything. The damage is not incidental but structural—built into how they relate to everyone.

DSM-5 criteria require a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy, as evidenced by five or more specific features. But beneath these criteria lies deeper pathology: a false self constructed to hide deep emptiness; Splitting Splitting A psychological defence mechanism involving all-or-nothing thinking where people or situations are seen as entirely good or entirely bad, with no middle ground. that divides world into all-good ideal objects and all-bad persecutors; projection that attributes one’s own unacceptable qualities to others; inability to maintain stable sense of self across time and situations; and fundamental disconnection from authentic emotional experience.

Research identifies two pathological narcissism subtypes with distinct presentations: grandiose narcissists display overt superiority, extraverted self-promotion, interpersonal dominance, and emotional resilience (or at least its appearance) 989 . Vulnerable narcissists display covert grandiosity hidden by insecurity, introverted self-protection, hypersensitivity to slight, and emotional fragility. Both meet NPD criteria but require different therapeutic approaches.

Treatment response reveals the distinction between traits and disorder. Someone with narcissistic traits might enter therapy for depression, form working alliance, and gradually address self-centred patterns creating relationship problems. Someone with full NPD cannot form alliance, rejects the premise that their patterns create problems, and typically exits treatment when the therapist stops providing validation. The quantitative difference (more severe traits) becomes qualitative difference (fundamentally different relationship to self and reality).

Kernberg’s distinction between “narcissistic personality disorder” and “ Malignant Narcissism Malignant Narcissism The most severe form of narcissism, combining NPD traits with antisocial behaviour, sadism, and paranoia—representing a dangerous intersection of personality pathology. ” adds another level—malignant narcissism combines NPD with antisocial features, ego-syntonic aggression, and paranoid traits 650 . These individuals willingly harm others without remorse and experience cruelty as justified. They are even more dangerous and treatment-resistant than standard NPD. They approach psychopathy while maintaining narcissism’s grandiose self-structure. Treatment is contraindicated except in secure settings where they cannot harm others or therapists.

If you have encountered malignant narcissism, you know it in your body before your mind names it. The ex who did not merely leave but conducted a campaign to destroy your reputation, your finances, your relationships with mutual friends. The business partner who embezzled while framing you for their theft. The parent whose abuse was not impulsive but calculated—who enjoyed your suffering. These individuals are not merely difficult or even disordered; they are dangerous. The only appropriate response is distance. The fantasy that therapy might help them is itself a trap.

Clinical Implications of the Spectrum

Narcissism’s spectrum significantly affects treatment approach and expectations. For healthy narcissism, no treatment is needed—this is psychological health. For narcissistic traits, focused psychotherapy can often achieve significant improvement. For narcissistic personality disorder, modest gains after years of treatment represent success. For malignant narcissism, containment and harm reduction become the goal rather than cure.

The spectrum also affects who presents for treatment. People with healthy narcissism never present—they are functioning well. People with narcissistic traits sometimes present, usually after relationship or career problems force self-examination. People with NPD rarely present unless mandated or during Narcissistic Collapse Narcissistic Collapse A severe breakdown of the narcissist's false self defences, exposing the shame and emptiness beneath, often triggered by major life failures or loss of supply. . People with malignant narcissism only present through forensic/legal systems or rarely during incarceration.

Selection bias in outcome research follows. Studies of “narcissistic personality disorder treatment” typically include subclinical cases (narcissistic traits) because full NPD patients do not stay in treatment long enough for inclusion. Success rates inflate, making treatment appear more effective than it is for severe cases. The literature’s “successfully treated narcissists” are often trait-level cases who would have been classified differently under stricter criteria.

Different severities call for different treatment modalities. Brief cognitive therapy might address specific narcissistic traits. Long-term psychodynamic therapy might be necessary for personality disorder. Medication might help comorbid conditions at trait level but has limited effect on core NPD. Group therapy might benefit covert narcissistic traits but traumatise or be disrupted by overt NPD. Tailoring approach to severity level optimises scarce therapeutic resources.

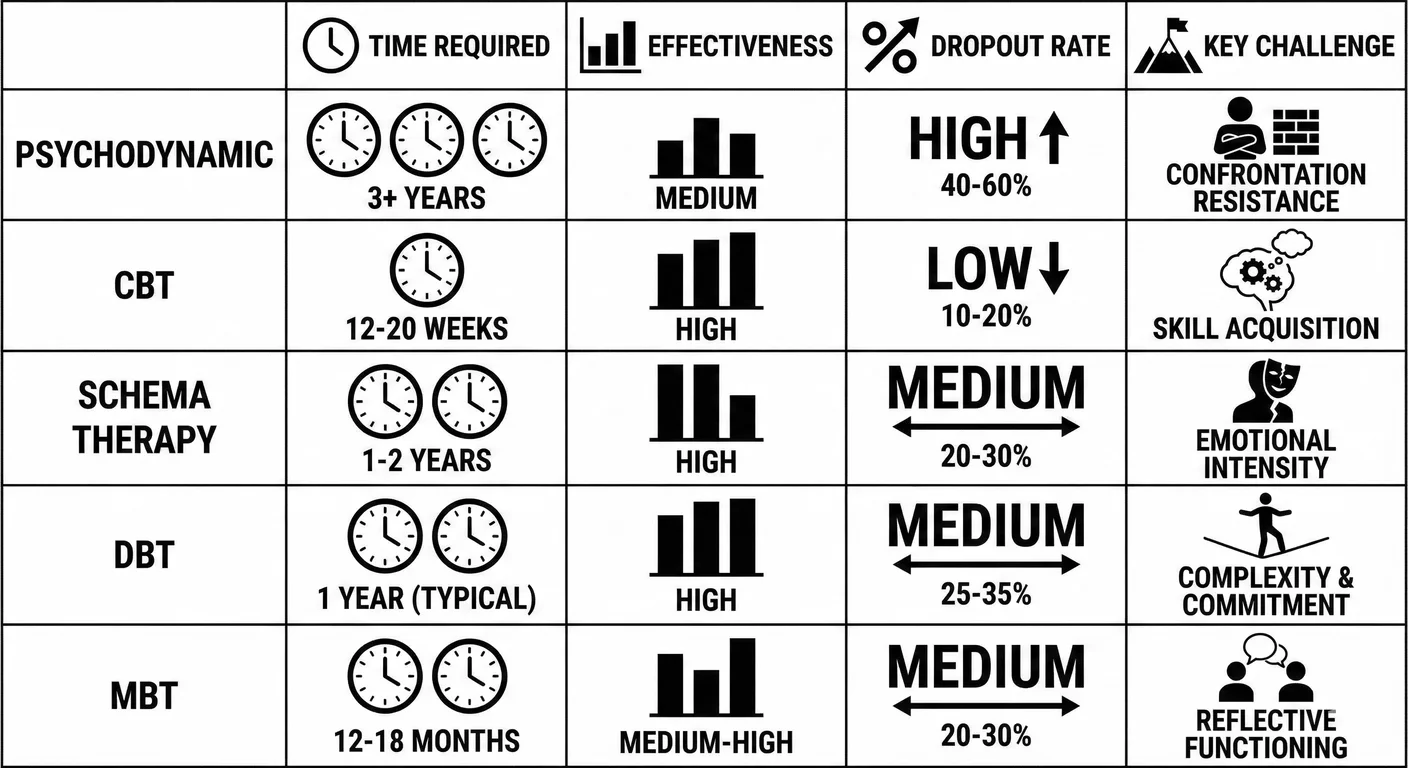

Therapeutic Approaches and Their Efficacy

Psychodynamic Approaches

Traditional psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy have the longest history treating narcissistic pathology. Freud’s original formulation of narcissism emerged from psychoanalytic practice. Subsequent analysts—Kernberg, Kohut, Masterson—developed sophisticated models of narcissistic development and treatment. Yet despite this theoretical sophistication, outcomes remain disappointing.

Kernberg’s approach emphasises confrontation of narcissistic defences—the therapist systematically interprets grandiosity, points out contradictions, and challenges the false self 649 . This technique, called “expressive psychotherapy,” aims to help patients face the emptiness beneath grandiosity. Kernberg argues that only by confronting defensive structure can authentic self emerge. However, this approach requires highly skilled therapists and produces massive resistance. Most narcissistic patients flee such confrontation rather than engage it.

Kohut’s contrasting approach emphasises empathic understanding and mirroring—rather than confronting defences, the therapist provides corrective emotional experience, the empathic attunement the narcissist never received in childhood 674 . This “supportive” approach creates safer therapeutic environment where narcissists might gradually develop authentic self-regard. Critics argue this approach colludes with narcissism, providing more validation rather than challenging pathology. Supporters counter that confrontation drives patients away while empathy enables engagement.

Transference focused psychotherapy (TFP), developed by Clarkin, Yeomans, and Kernberg, represents modern psychodynamic approach specifically designed for personality disorders—a highly structured twice-weekly treatment based on object relations model, shown effective for borderline personality disorder in randomised trials 251 . TFP systematically analyses the patient’s perceptions of therapist, using these transference patterns to illuminate relationship dynamics. With borderline patients, TFP shows good efficacy. With narcissistic patients, engagement remains the primary challenge. Many drop out when transference interpretations threaten grandiose self-concept.

Time poses the central problem. Successful cases require years of multiple-weekly sessions—an intensity and duration few narcissists tolerate. Even highly motivated patients struggle with the slow pace and emotional demands. Insurance rarely covers the necessary treatment length. The approach may be theoretically sound but practically unworkable for most cases.

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy

Cognitive therapy (CBT) offers more structured, time-limited approach focusing on dysfunctional thinking patterns and maladaptive behaviours. Aaron Beck and colleagues developed cognitive therapy specifically for personality disorders, including narcissism 94 . The approach identifies and challenges narcissistic cognitive schemas: “I am special and deserving of special treatment”; “Others exist to meet my needs”; “Rules apply to others, not me”; “My feelings and needs are more important than others’.”

CBT’s structured format and focus on specific problems appeals to some narcissistic patients more than psychodynamic approaches’ ambiguity. The therapist and patient collaboratively identify problematic thinking, examine evidence for and against these thoughts, and practice alternative perspectives. This empirical approach sidesteps some narcissistic defensiveness by framing change as logical rather than emotional.

CBT faces significant challenges with narcissism. The collaborative relationship CBT assumes—therapist and patient as co-investigators of thought patterns—violates narcissistic need for superiority. Narcissists often refuse to accept that their thinking is problematic. They view cognitive restructuring exercises as insulting attempts to gaslight them out of accurate perceptions. The homework assignments CBT uses often do not get completed or get completed superficially to please or impress the therapist rather than genuinely engage the work.

Schema Therapy Schema Therapy An integrative therapy developed by Jeffrey Young that addresses deep-rooted patterns (schemas) developed in childhood. Particularly effective for personality disorders and chronic issues where early maladaptive schemas—formed through unmet emotional needs—continue to shape adult life. , developed by Jeffrey Young, extends CBT by incorporating psychodynamic and attachment concepts. This integrative psychotherapy addresses early maladaptive schemas—pervasive dysfunctional patterns developed in childhood—showing high effectiveness for borderline personality disorder 1351 . For narcissists, common schemas include defectiveness/shame (hidden beneath grandiosity), entitlement, and insufficient self-control. Schema Therapy uses cognitive, behavioural, experiential, and relationship-focused techniques to modify these schemas.

Limited research on schema therapy for narcissism shows modest promise. Studies found Schema Therapy outperformed Transference-Focused Psychotherapy Transference-Focused Psychotherapy An evidence-based psychodynamic treatment for personality disorders that uses the patient's relationships patterns as they emerge with the therapist (transference) to understand and change deep-seated interpersonal patterns. for borderline personality disorder 452 . Similar trials for narcissism show some patients benefit, though dropout rates remain high. The approach’s attention to childhood wounds may engage narcissists more than pure CBT, but the length of treatment (typically one to three years) tests their limited tolerance for therapy.

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Skills Training

dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), developed by Marsha Linehan for borderline personality disorder, has transformed BPD treatment—combining cognitive restructuring with mindfulness and behavioural strategies as the gold-standard treatment for BPD and related conditions 748 . DBT combines cognitive-behavioural techniques with mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness skills. The approach is highly structured, with individual therapy, skills group, phone coaching, and therapist consultation team.

DBT was designed for borderline self-destructive behaviours, though some of its components might address narcissistic deficits. Mindfulness training could potentially help narcissists become aware of authentic internal states beneath the false self. Emotion regulation skills might address the shallow emotional life characterising narcissism. Interpersonal effectiveness training could teach relationship skills narcissists never developed.

Adapting DBT for narcissism faces major obstacles. DBT assumes patient motivation to change driven by suffering from their own behaviour. Borderline patients hurt themselves and desperately want this to stop. Narcissistic patients hurt others and do not experience this as their problem. DBT’s skills groups require capacity to learn from peer feedback, but narcissists dismiss peer input as inferior. The phone coaching component requires vulnerability and help-seeking that narcissists avoid.

Limited attempts to adapt DBT for narcissism have produced disappointing results. Narcissistic patients attend skills groups irregularly, complete homework superficially if at all, do not use phone coaching, and drop out at high rates. The few who complete treatment show modest improvement in specific behaviours but no fundamental personality change. DBT’s impressive success with borderline pathology does not extend to narcissistic pathology, reinforcing how fundamentally different these disorders are.

Mentalisation-Based Treatment

Mentalization-Based Treatment Mentalization-Based Treatment A psychotherapy developed by Peter Fonagy and Anthony Bateman that focuses on strengthening the capacity to understand behavior in terms of mental states. Originally developed for borderline personality disorder, it's effective for attachment-related issues. (MBT), developed by Peter Fonagy and Anthony Bateman, focuses on enhancing Mentalization Mentalization The capacity to understand behavior—in ourselves and others—in terms of underlying mental states like thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions. Narcissists show deficits in this crucial social-emotional skill. 405 . Mentalization deficits characterise many personality disorders. For narcissists specifically, the severe empathy deficit reflects impaired mentalisation of others’ mental states.

MBT uses structured individual and group therapy (incorporating Yalom’s therapeutic factors) to enhance mentalising through: identifying and labelling emotional states in self and others; considering multiple perspectives on interactions; distinguishing thoughts from feelings; recognising that others have different (not wrong, different) perspectives than oneself; and pausing before reacting to consider the mental states driving behaviour.

For borderline patients, MBT shows excellent outcomes, comparable to DBT. For narcissistic patients, results prove less impressive but more promising than many alternatives. MBT’s non-confrontational stance and focus on understanding rather than changing may reduce narcissistic defensiveness. The emphasis on developing capacity rather than acknowledging flaws frames work as skill-building rather than admitting deficits.

Group MBT for narcissism faces challenges similar to other group approaches—narcissists dominate discussion, dismiss others’ input, and use group as audience rather than source of learning. However, skilled group leaders can sometimes manage these dynamics by consistently refocusing on mentalising: “You just dismissed Tom’s feedback. Can you pause and consider what he might be experiencing that led him to offer that perspective?” This focus on process rather than content may sidestep some narcissistic resistance.

Dr Yolanda Reyes, a clinical psychologist in Los Angeles, describes treating a patient named Victor over six years. “We tried everything. Started with CBT because he liked the structure—he could treat it like a game he was winning. But he never did the homework, and when I pointed out thinking errors, he’d argue I was the one with distorted thinking.” She shifted to schema therapy. “We made some progress identifying his defectiveness schema, the shame underneath. But whenever we got close to it, he’d miss sessions, show up late, change the subject.” She tried MBT. “The mentalising exercises were useful—he got better at predicting how others would react. But it was strategic, not emotional. He was learning to simulate empathy, not feel it.” After his second divorce, Victor experienced collapse. “That’s when we finally had six months of real work. He could tolerate knowing he’d caused damage. Then he got a new girlfriend who thought he was wonderful, and he terminated.” What would she tell other therapists? “Lower your expectations. I helped Victor hurt fewer people, maybe. He’s still Victor.”

Couples and Family Therapy

Narcissists often present for treatment in couples therapy, dragged reluctantly by suffering partners threatening to leave unless things change. Both opportunity and danger follow from this. The opportunity: narcissists might engage to preserve relationships providing validation. The danger: they often use couples therapy to triangulate therapist against partner, manipulate professional validation of their position, or demonstrate partner’s inadequacy to expert witness.

Successful couples therapy with a narcissistic partner requires exceptional therapist skill. The therapist must maintain neutrality while not colluding with narcissistic framing, confront narcissistic behaviour without triggering rageful exit, give the narcissistic partner enough validation to remain engaged, protect the non-narcissistic partner from retraumatisation, and somehow help the couple understand their dynamics without the narcissist experiencing this as attack.

Many experienced couples therapists refuse to work with narcissistic individuals, having learned that these cases often end badly. The narcissist either drops out when therapy does not validate their position, or wages a covert campaign to turn therapist against partner, or successfully triangulates therapist into the dysfunctional dynamic. The non-narcissistic partner often ends up more confused and damaged than before, now questioning their perceptions because the therapist “did not see” the narcissistic behaviour (which the narcissist carefully hides in sessions).

Family therapy with narcissistic parents faces similar challenges magnified by power differentials. Children cannot safely describe parental narcissism without risk of retaliation. The narcissistic parent uses therapy to demonstrate what a caring parent they are. Therapists feel pressure to maintain family cohesion rather than name abuse. Adult children of narcissistic parents often describe family therapy as retraumatising experience where their reality was invalidated and they were blamed for family dysfunction.

The exceptions—couples/family therapy that successfully addresses narcissistic dynamics—typically occur when the therapist has extensive personality disorder training, the narcissistic individual faces strong external motivation (court mandate, employer requirement, or genuine fear of relationship loss), the therapy is highly structured with clear behavioural goals, and the non-narcissistic parties have independent support protecting them from retaliation. Even then, success means modest behavioural change, not personality transformation.

Neurobiological and Pharmacological Considerations

The Narcissistic Brain

Neuroscience research illuminates why narcissism is so treatment-resistant by revealing structural and functional brain differences in narcissistic individuals. These are neurobiological realities, not simply psychological patterns. While this could seem hopeless—you cannot change your brain structure through willpower—it also suggests potential biological interventions and helps explain treatment failures.

Structural MRI studies examining grey matter volume in individuals high versus low on narcissistic traits found that high-narcissism individuals showed less grey matter in the anterior insular cortex—a region involved in empathy and emotional awareness—compared to low-narcissism controls 370 . This structural difference appears to reflect developmental variation rather than environmental damage, suggesting that narcissistic brains may have less neural tissue in regions supporting empathy.

Functional MRI studies indicate how narcissistic brains may process social information differently. When narcissists view faces expressing distress, they tend to show reduced activation in anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex—regions that normally create the visceral, automatic response to others’ suffering that motivates helping 603 . These findings suggest narcissistic empathy deficits may have biological as well as psychological components.

The reward system in narcissistic brains shows hyperactivation to social admiration and status. When receiving praise or winning competitions, narcissists show exaggerated activation in the ventral striatum, the brain’s reward centre, compared to controls. Narcissistic behaviour is literally more rewarding at neurological level—the brain’s response reinforces narcissistic patterns. Trying to change behaviour that produces such strong neurobiological rewards faces steep odds.

In everyday terms: when a colleague compliments your presentation, you feel good briefly and move on. When someone compliments the narcissist’s presentation, their brain responds like a gambler hitting jackpot—a surge of dopamine far exceeding normal pleasure response. This explains the relentless pursuit of admiration: they are chasing a high that non-narcissists simply do not experience. It also explains why they cannot “just stop” seeking validation any more than an addict can simply decide to stop craving their substance. The behaviour is neurologically reinforced at a level willpower cannot easily override.

The picture is more complex than simple brain deficits. Some research suggests narcissists can empathise when specifically instructed to do so—their empathy requires conscious, effortful engagement rather than automatic activation 544 . This implies potential for therapeutic intervention: teaching narcissists to deliberately activate empathic processing that does not occur automatically. Whether they would maintain such effortful empathy outside therapy remains doubtful, but narcissistic empathy deficits may not be completely hardwired.

Neuroplasticity and the Possibility of Change

The brain’s neuroplasticity—its capacity to rewire through experience—offers theoretical hope for treating narcissism. If narcissistic brain patterns developed through early experience (attachment failures, trauma, genetic vulnerabilities interacting with environment), then new experiences might reshape these patterns. Prolonged psychotherapy aims to provide such new experience, gradually rewiring neural pathways through repeated emotional experiences.

Research on neuroplasticity demonstrates that sustained, focused effort can create measurable brain changes—Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for depression creates detectable changes in prefrontal cortex activity 319 . Mindfulness meditation increases grey matter density in regions associated with emotion regulation 568 . If therapeutic intervention can change brains for other conditions, why not narcissism?

Neuroplastic change requires three conditions rarely met in narcissistic treatment. Sustained engagement over extended time—but narcissists typically drop out before sufficient neural rewiring could occur. Emotional engagement with new experiences—but the false self prevents authentic emotional engagement, going through therapeutic motions without genuine involvement. Repetition in daily life beyond therapy—but narcissists often compartmentalise therapy, performing in sessions without applying learning elsewhere.

A few case reports describe narcissistic patients who remained in treatment for years, gradually showing both psychological change and (when scanned) neurobiological changes in empathy-related regions. But these exceptional cases cannot be generalised. They typically involved unusual circumstances: narcissistic collapse creating genuine motivation, exceptional therapist skill, and strong external incentives to remain engaged. For most narcissists, the time required for neuroplastic change exceeds their tolerance for therapy.

Pharmacological Interventions

Narcissistic personality disorder has no effective pharmacological treatment. No medication addresses the core features of grandiosity, empathy deficit, and interpersonal exploitation. This therapeutic poverty reflects that NPD is a personality structure developed over a lifetime, with no chemical imbalance to correct. Pills cannot reorganise personality.

Medications can address comorbid conditions common in narcissistic individuals. Severe depression frequently follows narcissistic collapse when the grandiose self fails catastrophically. SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) may alleviate this depression, potentially creating a window for therapeutic engagement. But the depression treatment does not affect underlying narcissism—once depression lifts and narcissistic defences reconstitute, the personality disorder remains intact.

Anxiety frequently accompanies vulnerable narcissism—the constant fear that the false self will be exposed. Anti-anxiety medications like SSRIs or benzodiazepines may reduce this anxiety. But again, this treats symptom rather than personality structure. The vulnerable narcissist taking anti-anxiety medication still has narcissistic personality disorder; they are just less anxious about it.

Substance abuse and other comorbidity commonly co-occur with narcissism, often representing self-medication for underlying emptiness or self-soothing when validation is insufficient. Treating the substance abuse through medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioids or alcohol can improve functioning. But the personality disorder driving the substance abuse remains. Many narcissists substitute one addiction for another once the primary substance is controlled.

Some clinicians prescribe mood stabilisers such as lithium and valproate for narcissistic patients showing affective instability—the rage episodes and emotional dysregulation. These medications may reduce impulsive aggression and mood swings. Limited evidence suggests some benefit, but the effect is modest. The narcissistic structure generating the affective instability persists; the medication just dampens its expression.

Stimulant medications prescribed for comorbid ADHD—common in narcissists whose impulsivity and attention seeking may be misdiagnosed as ADHD—can paradoxically worsen narcissism. The increased focus and productivity stimulants provide may reinforce grandiose self-concept. The energy boost may intensify narcissistic behaviours. Careful evaluation distinguishing genuine ADHD from narcissistic impulsivity is essential before prescribing stimulants.

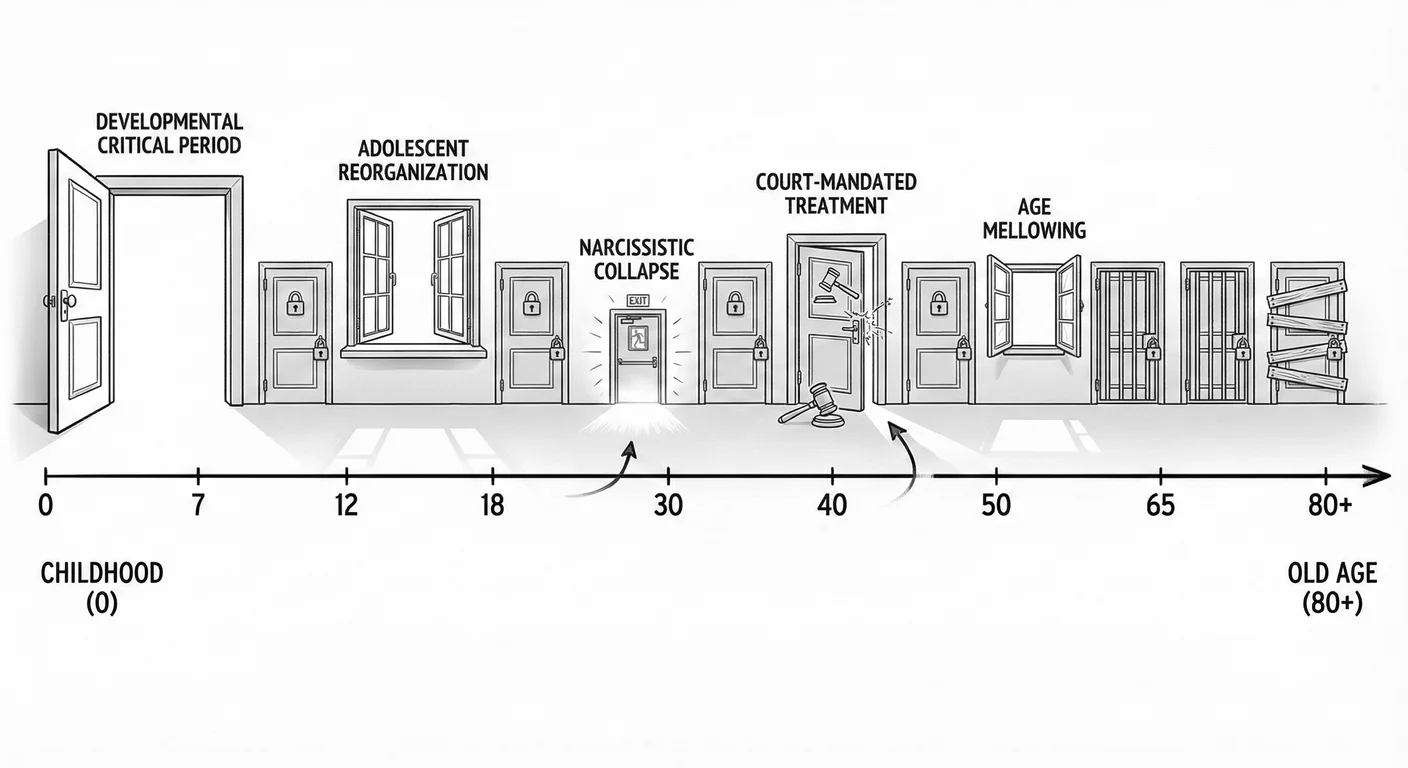

Windows of Opportunity—When Change Becomes Possible

Narcissistic Collapse as Treatment Catalyst

Narcissists rarely seek treatment voluntarily, but one circumstance reliably brings them to therapists’ offices: Narcissistic Collapse Narcissistic Collapse A severe breakdown of the narcissist's false self defences, exposing the shame and emptiness beneath, often triggered by major life failures or loss of supply. (Chapter )—the catastrophic failure of the false self when supply sources are severed. Career failure, romantic rejection, public humiliation, legal troubles, or aging-related losses can trigger this crisis.

Picture the executive who built his identity around professional dominance, now cleaning out his desk after the board voted him out. The woman whose beauty secured her narcissistic supply for decades, now watching her reflection betray her. The patriarch whose family has finally stopped returning his calls. In these moments, the false self cannot maintain its illusions. The grandiosity collapses. And in that collapse, something remarkable sometimes happens: the narcissist, for perhaps the first time, feels genuine pain—not injury at being slighted, but grief at what they have become.

This suffering opens a therapeutic window. Defences weaken. Authentic engagement becomes briefly possible.

But the window closes quickly. As soon as sufficient stability returns, narcissistic defences reconstitute. The grandiose self rebuilds, often more rigidly than before. The executive finds a new company to dominate; the aging beauty finds a younger partner to mirror her; the patriarch finds new people who do not yet know to avoid him. The brief period of vulnerability and self-awareness vanishes as if it never occurred. Therapists working with collapsed narcissists face a cruel race against time: can sufficient therapeutic progress occur before defences reconstitute and the patient exits treatment?

Court-Mandated Treatment

Legal mandate also brings narcissists to treatment—court-ordered therapy following domestic violence, DUI, assault, or white-collar crime. The dynamic differs sharply from voluntary treatment. The narcissist is not there for self-improvement but to satisfy external requirements and receive documentation enabling them to avoid harsher consequences.

Mandated treatment poses special challenges. The narcissist views therapy as punishment to be endured rather than help to be embraced. They perform compliance superficially—attending sessions, saying appropriate things, completing required tasks—while maintaining contemptuous internal attitude and no genuine engagement. They seek to charm or manipulate the therapist into providing favourable reports to the court, using the same interpersonal strategies that created legal troubles in the first place.

The therapist sees through this, of course. But what can be done? The narcissist sits in the chair, says the words, watches the clock. The same charm that convinced investors, that seduced partners, that won over juries—now deployed to produce a progress report.

And yet mandated treatment has one advantage: time. Unlike voluntary treatment where narcissists can exit at will, mandated treatment continues for court-specified duration. This enforced engagement provides an opportunity for therapeutic relationship development and gradual insight accumulation that voluntary treatment rarely allows. Some narcissists, forced to remain in therapy longer than they would voluntarily, eventually develop genuine engagement despite initial resistance. The performance becomes, unexpectedly, real.

Successful mandated treatment requires clear behavioural goals that can be objectively assessed (attending sessions, completing assignments, demonstrating specific skills), honest reporting to the court about progress rather than enabling narratives, therapist skill at maintaining professional boundaries while avoiding power struggles, and sufficient treatment length—months to years rather than weeks.

Even successful mandated treatment typically produces behavioural compliance rather than personality change. The narcissist learns to control behaviours that caused legal trouble—stops hitting partner, stops driving drunk, stops embezzling—yet the underlying narcissistic structure remains. They comply because consequences are clear, not because they have developed empathy for victims or genuine insight into their behaviour. Is this success? The partner no longer gets hit. The victims are fewer. By any practical measure, yes—even if the personality disorder persists.

Age and the Mellowing Effect

Longitudinal studies indicate that narcissistic traits decrease with age. People in their 20s and 30s show higher narcissism than those in their 50s and 60s. This “mellowing effect” occurs across multiple cultures and appears to be a developmental pattern rather than cohort effect.

Why does time soften what therapy cannot?

Reality imposes increasing constraints on grandiosity. Young narcissists can maintain illusions of unlimited potential—“I am going to be famous/rich/powerful.” By middle age, realistic assessment becomes unavoidable. Career trajectories are established. Looks fade. Health declines. Financial limitations are clear. The grandiose self cannot maintain its illusions against accumulated evidence. The man who at thirty believed he would run the company now, at fifty-five, reports to someone younger. The woman who built her identity on turning heads now walks through rooms unnoticed. Some narcissists adapt by scaling down grandiosity to match reality—not insight, exactly, but accommodation.

Aging also reduces energy for narcissistic behaviour. The constant performance required to maintain the false self becomes exhausting. Managing multiple validation sources and maintaining false impressions requires energy that diminishes with age. Older narcissists may become less actively destructive simply from fatigue. The games they once played with enthusiasm now feel like too much work.

The losses aging brings sometimes crack narcissistic defences. Death of parents, serious illness, retirement, or grandparenthood can trigger existential reflection. Some older narcissists, confronted with mortality, experience genuine regret about damaged relationships and wasted opportunities for authentic connection. The grandchild who looks at them with uncomplicated love; the old friend who still calls despite everything; the spouse who stayed—these become precious in ways that younger narcissists cannot comprehend. This late-life wisdom rarely produces fundamental character change, but may create motivation for amends and behaviour modification.

Not all narcissists mellow. Some become more bitter and difficult with age, experiencing every natural loss as Narcissistic Injury Narcissistic Injury A perceived threat to a narcissist's self-image that triggers disproportionate emotional reactions including rage, shame, humiliation, or withdrawal. and responding with increasing rage and entitlement. You know these elders: the grandmother who poisons every family gathering with grievances, the retired executive who treats waiters like subordinates, the aging patriarch whose children dread holiday visits. The narcissistic collapse that aging triggers can become permanent state rather than temporary crisis. These individuals become tyrannical elders, their narcissism intensifying rather than mellowing. The clinical question is why some narcissists mellow while others embitter—research has not yet identified reliable predictors.

Therapeutic Expertise and Matching

The therapist’s characteristics significantly affect whether narcissistic treatment succeeds or fails. Not all therapists are equally equipped for this challenging work. Effective therapists of narcissistic patients show exceptional patience and frustration tolerance, capacity to tolerate being devalued without becoming defensive, ability to find and connect with the wounded person beneath grandiosity, skill at setting and maintaining boundaries without power struggles, and genuine compassion for the deep suffering behind narcissistic defences.

Research on therapist vulnerabilities identifies several types particularly unsuited for narcissistic patients 431 . Therapists with their own narcissistic traits may compete with patients rather than help them. Therapists with strong caretaking needs may enable narcissistic behaviour seeking patient approval. Therapists with fragile self-esteem may be too wounded by narcissistic devaluation to maintain therapeutic stance. Therapists who need to be liked may collude with narcissistic defences rather than confronting them.

Certain therapist types handle narcissistic patients well. Therapists who have worked through their own narcissistic injuries understand the dynamics experientially. Therapists with strong personal boundaries can set limits without hostility. Therapists comfortable with power can accept one-up position without defensiveness or need to dominate. Therapists who genuinely appreciate the terror beneath grandiosity can maintain compassionate stance through devaluation and manipulation.

The therapeutic match matters enormously. An older, established therapist with strong professional identity may handle narcissistic devaluation easily while a younger therapist still building confidence gets wounded. A therapist who values egalitarian relationships may struggle with narcissistic demands for special treatment while a therapist comfortable with hierarchy accommodates this. A highly empathic therapist may connect with vulnerable narcissism while being devastated by grandiose narcissistic attacks. Matching patient subtype and pathology level with appropriate therapist characteristics optimises the limited chances for successful treatment.

Realistic Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

What the Research Reveals

Long-term outcome studies of narcissistic personality disorder paint a sobering picture. Unlike borderline personality disorder, where 85% achieve remission over 10-20 years 1362 , narcissism shows much less improvement. Follow-up studies indicate that most narcissistic individuals show consistent stability in their pathology across decades. The grandiosity, empathy deficits, and interpersonal exploitation persist largely unchanged from early adulthood through old age.

Longitudinal research following narcissistic patients for an average of 15 years found that only about 25% showed significant improvement, and this improvement was typically partial rather than complete 1049 . The majority maintained their narcissistic personality organisation, though some learned to manage behaviours better or selected life circumstances minimising interpersonal damage. Complete personality reorganisation—fundamental change in character structure—occurred in less than 10% of cases. NPD’s prognosis remains sobering.

The factors predicting better outcomes included presence of depressive features suggesting some capacity for genuine self-reflection, younger age at treatment initiation before patterns become completely rigid, less severe pathology at baseline (trait level rather than full disorder), absence of antisocial features (which indicate malignant narcissism and very poor prognosis), and strong external motivation maintaining treatment engagement.

Factors predicting poor outcomes included early trauma or severe attachment disruption, comorbid substance abuse, antisocial personality features, history of violence, grandiose rather than vulnerable subtype, and absence of genuine suffering from the narcissistic patterns. Narcissists who damage only others but experience no personal distress have minimal motivation for change and correspondingly poor prognosis.

Comparing narcissistic outcomes to other personality disorders is instructive. Borderline personality disorder, once considered untreatable, now has an excellent prognosis with appropriate intervention. Antisocial personality disorder remains largely treatment-resistant but may improve with aging. Avoidant and dependent personality disorders often respond well to therapy. Narcissistic personality disorder falls towards the treatment-resistant end of the spectrum, second only to antisocial personality disorder in its intractability.

Defining Success in Treatment

Given narcissism’s treatment resistance, redefining “success” becomes necessary. Complete personality transformation—the narcissist becoming genuinely empathic and capable of mutual relationships—occurs so rarely that expecting this sets up inevitable disappointment. More realistic goals include behavioural improvement rather than character change, developing capacity to manage narcissistic traits rather than eliminating them, reducing harm to others even if the individual remains self-centred, and occasional access to authentic feelings beneath the false self.

Behavioural improvement means the narcissist learns to control destructive behaviours even while underlying drives persist. They may still crave validation but develop healthier ways of obtaining it. They may still feel superior but stop expressing this abusively. They may still lack empathy but learn to behave as if they care about others’ feelings. This represents success even if not cure.

Some narcissists develop “enlightened self-interest”—recognising that treating others better serves their own interests. They remain fundamentally self-centred but realise that exploiting others too obviously creates problems. They learn to fake empathy convincingly, modulate grandiosity in public, and manage impressions more skilfully. This falls short of genuine change but represents improvement over unchecked narcissism.

For families and partners, success might mean the narcissist accepts couples therapy and modifies specific behaviours causing greatest distress. The narcissistic parent might stop the most damaging behaviours even without developing genuine love for children. The narcissistic partner might reduce rage episodes and Gaslighting Gaslighting A manipulation tactic where the abuser systematically makes victims question their own reality, memory, and perceptions through denial, misdirection, and contradiction. even without becoming truly intimate. These modest gains, while falling far short of ideal, represent meaningful improvement over untreated narcissism.

Clinical example: Amanda worked with narcissistic husband Greg in couples therapy for three years. Greg never developed genuine empathy or insight into his narcissism. But he did learn to catch himself before launching into contemptuous critiques of Amanda. He developed habit of asking “How was your day?” even though he did not particularly care about the answer. He stopped rageful outbursts after Amanda established firm consequence (she would leave if he screamed at her again). Their relationship remained fundamentally asymmetrical, but became tolerable rather than abusive. Amanda decided this limited progress was sufficient to continue the marriage. While many would consider this tragic settling, it represented real improvement over the baseline situation.

The Intractability Problem

Why is narcissism so intractable compared to other personality disorders?

Narcissism is ego syntonic —the person experiences their narcissistic traits as positive qualities rather than problems. The borderline experiences their emotional chaos as distressing. The avoidant experiences their social anxiety as limiting. The narcissist experiences their grandiosity as accurate self-perception and their lack of empathy as evidence they are not weak like others. Treatment requires recognising that your greatest strengths are actually severe deficits—an insight narcissistic psychology renders nearly impossible.

Narcissism creates its own rewards and reinforcements. Narcissistic behaviour often brings real success, at least short-term. The confident self-promotion gets attention. The ruthless exploitation achieves goals. The lack of empathy enables difficult decisions. Even when narcissism creates long-term problems, the immediate rewards are powerful. A reinforcement schedule maintains narcissistic behaviour despite eventual consequences.

Narcissism affects the very capacities required for therapeutic change. Insight, self-reflection, ability to tolerate discomfort, willingness to accept feedback, capacity to form genuine relationship with therapist—narcissistic pathology compromises them all. The disorder disables exactly the psychological equipment needed to treat it. A vicious cycle operates: the more severe the narcissism, the less treatable it becomes.

Narcissism may have stronger biological and genetic basis than previously recognised. The brain studies showing structural differences suggest developmental origins not easily modified through experience. Twin studies indicate higher heritability for narcissistic traits than for some other personality features. If narcissism has substantial hardwired component, purely psychological interventions face inherent limitations.

\clearpage

Guidance for Therapists and Families

For Therapists Considering Treating Narcissistic Patients

Therapists must make informed decisions about whether to work with narcissistic patients. Many excellent therapists choose to avoid treating narcissism after learning its challenges—a legitimate clinical choice. For those who do choose this work, certain principles optimise chances for success and minimise personal cost.

Conduct thorough clinical assessment before committing to treatment. Distinguish narcissistic traits (treatable) from full personality disorder (marginally treatable at best). Identify motivation level—is the person genuinely distressed by their patterns or just seeking therapist as validation source? Assess capacity for insight—can they recognise any problems in their own behaviour or is everything externalised? Evaluate treatability factors: presence of depression, vulnerable subtype features, history of any meaningful relationships.

Establish clear contract early in treatment. Define specific behavioural goals rather than vague personality change objectives. Set boundaries about acceptable behaviour in therapy (“You may feel angry with me, but you may not scream at me or insult me”). Clarify consequences for contract violations (“If you miss three consecutive sessions without explanation, I will terminate treatment”). Get explicit agreement to these terms before beginning substantive work.

Maintain strong therapeutic boundaries. Do not accept late-night phone calls, extended sessions, or special treatment requests. Do not disclose personal information beyond what is therapeutically necessary. Do not socialise with narcissistic patients outside professional context. Do not accept gifts or favours. These boundaries protect both parties and model healthy relationship parameters.

Use supervision or consultation religiously. Working with narcissistic patients is emotionally taxing and professionally challenging. Regular consultation with experienced colleagues provides a reality check when the individual’s distortions become convincing. Supervision helps process transference and countertransference—the therapist’s emotional reactions to the patient’s behaviour. Without external perspective, therapists risk either becoming punitive or enabling narcissistic pathology.

Know your own limits and respect them. If you find yourself dreading sessions with a patient, developing contempt for them, or fantasising about their termination, these danger signs suggest you may be unsuited for treating this particular person or narcissism generally. Refer the patient to another therapist before the therapeutic relationship harms either party. Acknowledging that certain pathologies exceed your clinical capacities carries no shame.

For Families Hoping Their Narcissistic Relative Will Change

Families of narcissistic individuals often hold onto hope that their relative will eventually recognise their problems and seek help. This hope sustains them through years of abuse and exploitation. Therapists face the difficult task of balancing realistic assessment with compassion for the family’s situation.

Most narcissists never seek treatment, and most who do seek treatment drop out quickly without significant change. Families need to know these odds before making life decisions based on unrealistic expectations of transformation. How many years will you wait? How many holidays ruined, how many conversations twisted, how many tears shed—waiting for an awakening that statistics suggest will never come?

Some families cannot or will not leave the narcissistic relationship. The mother cannot abandon her narcissistic adult son. The brother feels obligated to maintain contact with his sister despite everything. The wife faces financial ruin or religious sanction if she divorces. For these families, the therapeutic task shifts from encouraging separation to supporting survival within the relationship.

Survival begins with radical acceptance that the narcissist will not change. This acceptance, paradoxically, reduces frustration and disappointment. You stop waiting. You stop hoping. You grieve what the relationship will never be, and you make peace with what it is. From this foundation, firm boundaries about acceptable behaviour become possible. Not ultimatums delivered in anger, but quiet lines drawn and held. “I will not discuss my weight with you.” “I will leave if you raise your voice.” “I will not lend you money again.” The narcissist will test these boundaries. Consistency is everything.

Essential too is a support network outside the narcissistic relationship. Friends who believe you. A therapist who understands. Perhaps a support group for families of narcissists, where others who have lived this recognise your experience without requiring explanation. Equally necessary are practices protecting your own psychological wellbeing. Therapy. Exercise. Time in nature. Whatever refills what the narcissist depletes.

Some families find that strategic approach minimises damage—providing enough validation to prevent rage while not enabling abuse, avoiding triggering narcissistic injury through careful communication, framing requests in terms of the narcissist’s self-interest rather than expecting empathic response. This is not manipulation; it is adaptation. You learn the terrain and navigate accordingly.

This approach represents realistic adaptation rather than healthy relationship. But for families unable or unwilling to completely separate from narcissistic relatives, such strategies represent harm reduction if not healing. Support groups can provide essential assistance in navigating these difficult relationships.

When to Stop Trying

When should you stop investing energy in trying to help a narcissistic individual change? For therapists, this means when to terminate treatment. For families, it means when to accept that the relationship will never improve and make peace with this or end contact.

For therapists, clear termination indicators include patient repeatedly violating therapeutic contract without addressing violations, patient using therapy destructively (manipulating the therapist to harm others or seeking validation for abusive behaviour), patient showing no engagement after a reasonable trial period of six to twelve months, patient’s behaviour towards therapist becoming too destructive of therapist’s wellbeing, or the therapeutic relationship actively enabling patient’s narcissistic pathology rather than addressing it.

Terminating treatment with narcissistic patients requires care. They may experience termination as narcissistic injury and respond with rage, threats, complaints to licensing boards, or other retaliatory behaviours. Therapists should document thoroughly all violations of therapeutic contract, provide clear explanation of termination reasons citing specific behavioural patterns, offer referrals to other therapists (even knowing patient likely will not use them), and maintain professional demeanor even if patient becomes hostile.

For families, the decision to stop trying for change is deeply personal and often anguished. Some indicators suggesting this decision may be necessary: the family member’s narcissism causes severe ongoing harm (abuse, financial exploitation, psychological damage); the family member shows zero recognition of problems or interest in changing; attempts at intervention have failed repeatedly; the family’s efforts to help enable narcissistic behaviour; or maintaining the relationship causes such distress that family members’ own health and functioning decline.

Accepting unchangeability does not necessarily mean ending contact, though for some families this proves the healthiest choice. It can mean radically lowering expectations, establishing firm boundaries, accepting the relationship’s limitations, and focusing energy on one’s own life rather than fixing the narcissist. This acceptance often brings paradoxical relief: once the exhausting hope for change is relinquished, energy previously consumed by that hope becomes available for more productive uses.

Conclusion: Hope Within Honesty

After this sobering examination, we return to the chapter’s central question: Can Narcissus be healed? Honesty compels: rarely, slightly, and only under specific circumstances. Complete transformation from narcissistic personality disorder to psychological health represents a clinical unicorn—theoretically possible but so rare as to be negligible in practical treatment planning. Most narcissists never seek treatment, most who seek treatment drop out quickly, and most who complete treatment show minimal lasting change.

Some narcissists do change—the collapsed narcissist who finds motivation in crisis, the aging narcissist who mellows and regrets, the court-mandated narcissist who develops genuine insight over time, the narcissist with sufficient vulnerable features to engage authentic therapy. These exceptional cases, while not generalisable, demonstrate that change is possible even if improbable.

The spectrum matters. Narcissistic traits, falling short of full personality disorder, often respond much better to treatment. The person with narcissistic features who recognises that these create problems and genuinely wants to change has a reasonable prognosis. Distinguishing trait-level pathology from full personality disorder becomes important for realistic treatment planning and expectation management.

The therapeutic modalities reviewed—psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioural, schema therapy, Mentalisation-Based Treatment—all show some efficacy with carefully selected narcissistic patients who remain in treatment. The problem is engaging patients in those treatments long enough for change to occur, with potentially effective treatments already available. Future advances may come less from developing new treatment technologies than from understanding how to maintain therapeutic engagement with treatment-resistant populations.

Neuroscience offers both discouragement and hope. The structural and functional brain differences in narcissists help explain treatment resistance—you cannot simply think or feel your way to different brain architecture. Yet neuroplasticity demonstrates that brains can change through experience, suggesting that sustained therapeutic engagement might gradually rewire narcissistic neural patterns. Whether narcissists will ever tolerate the years of engagement necessary for such rewiring remains doubtful, but the theoretical possibility exists.

This chapter offers therapists and families guidance emphasising realistic expectations, self-protection, and strategic adaptation rather than transformation narratives. For therapists: careful case selection, strong boundaries, regular consultation, and willingness to terminate when treatment becomes harmful. For families: radical acceptance, strategic interaction, strong outside support, and sometimes the difficult decision to limit or end contact.

The cultural implications extend beyond individual treatment. If narcissism is largely untreatable at personality disorder level, prevention becomes paramount: preventing narcissism’s development and protecting people from narcissistic damage becomes the priority. Cultural interventions addressing the narcissism epidemic matter more than individual therapy for already-formed narcissistic personality disorder.

Honesty about treatment limitations serves important ethical function. Offering false hope to suffering families is cruel. Pretending that narcissists can easily change if they just try hard enough blames victims for not trying harder. Acknowledging the statistical reality that most narcissists will not change enables realistic decision-making about relationships, resources, and life planning. Hope within honesty means being clear-eyed about the odds while remaining open to the exceptional cases where genuine change occurs.

Narcissus, gazing at his reflection in the pool, could not tear himself away even as he wasted to death. This image captures narcissism’s tragedy: the person trapped by their own image, unable to see beyond it to authentic existence, dying from inability to love anything but their own reflection. For most Narcissuses, this remains their fate. But for the exceptional few, those who hit bottom hard enough to crack the mirror, those who encounter the right therapist at the right time, those with enough vulnerable features to engage genuine help, a different ending becomes possible. The modest redemption of a slightly more authentic life—distinct from the fairy tale transformation from narcissist to saint—slightly more genuine connection, slightly less damage inflicted on others and self. In treating narcissism, such modest gains represent notable success.